A Review of Ann Radcliffe, Romanticism and the Gothic (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2014)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature Edited by Eva-Marie Kröller Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-15962-4 — The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature Edited by Eva-Marie Kröller Frontmatter More Information The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature This fully revised second edition of The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature offers a comprehensive introduction to major writers, genres, and topics. For this edition several chapters have been completely re-written to relect major developments in Canadian literature since 2004. Surveys of ic- tion, drama, and poetry are complemented by chapters on Aboriginal writ- ing, autobiography, literary criticism, writing by women, and the emergence of urban writing. Areas of research that have expanded since the irst edition include environmental concerns and questions of sexuality which are freshly explored across several different chapters. A substantial chapter on franco- phone writing is included. Authors such as Margaret Atwood, noted for her experiments in multiple literary genres, are given full consideration, as is the work of authors who have achieved major recognition, such as Alice Munro, recipient of the Nobel Prize for literature. Eva-Marie Kröller edited the Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature (irst edn., 2004) and, with Coral Ann Howells, the Cambridge History of Canadian Literature (2009). She has published widely on travel writing and cultural semiotics, and won a Killam Research Prize as well as the Distin- guished Editor Award of the Council of Editors of Learned Journals for her work as editor of the journal Canadian -

Cahiers-Papers 53-1

The Giller Prize (1994–2004) and Scotiabank Giller Prize (2005–2014): A Bibliography Andrew David Irvine* For the price of a meal in this town you can buy all the books. Eat at home and buy the books. Jack Rabinovitch1 Founded in 1994 by Jack Rabinovitch, the Giller Prize was established to honour Rabinovitch’s late wife, the journalist Doris Giller, who had died from cancer a year earlier.2 Since its inception, the prize has served to recognize excellence in Canadian English-language fiction, including both novels and short stories. Initially the award was endowed to provide an annual cash prize of $25,000.3 In 2005, the Giller Prize partnered with Scotiabank to create the Scotiabank Giller Prize. Under the new arrangement, the annual purse doubled in size to $50,000, with $40,000 going to the winner and $2,500 going to each of four additional finalists.4 Beginning in 2008, $50,000 was given to the winner and $5,000 * Andrew Irvine holds the position of Professor and Head of Economics, Philosophy and Political Science at the University of British Columbia, Okanagan. Errata may be sent to the author at [email protected]. 1 Quoted in Deborah Dundas, “Giller Prize shortlist ‘so good,’ it expands to six,” 6 October 2014, accessed 17 September 2015, www.thestar.com/entertainment/ books/2014/10/06/giller_prize_2014_shortlist_announced.html. 2 “The Giller Prize Story: An Oral History: Part One,” 8 October 2013, accessed 11 November 2014, www.quillandquire.com/awards/2013/10/08/the-giller- prize-story-an-oral-history-part-one; cf. -

Governor General's Literary Awards

Bibliothèque interculturelle 6767, chemin de la Côte-des-neiges 514.868.4720 Governor General's Literary Awards Fiction Year Winner Finalists Title Editor 2009 Kate Pullinger The Mistress of Nothing McArthur & Company Michael Crummey Galore Doubleday Canada Annabel Lyon The Golden Mean Random House Canada Alice Munro Too Much Happiness McClelland & Steward Deborah Willis Vanishing and Other Stories Penguin Group (Canada) 2008 Nino Ricci The Origins of Species Doubleday Canada Rivka Galchen Atmospheric Disturbances HarperCollins Publishers Ltd. Rawi Hage Cockroach House of Anansi Press David Adams Richards The Lost Highway Doubleday Canada Fred Stenson The Great Karoo Doubleday Canada 2007 Michael Ondaatje Divisadero McClelland & Stewart David Chariandy Soucoupant Arsenal Pulp Press Barbara Gowdy Helpless HarperCollins Publishers Heather O'Neill Lullabies for Little Criminals Harper Perennial M. G. Vassanji The Assassin's Song Doubleday Canada 2006 Peter Behrens The Law of Dreams House of Anansi Press Trevor Cole The Fearsome Particles McClelland & Stewart Bill Gaston Gargoyles House of Anansi Press Paul Glennon The Dodecahedron, or A Frame for Frames The Porcupine's Quill Rawi Hage De Niro's Game House of Anansi Press 2005 David Gilmour A Perfect Night to Go to China Thomas Allen Publishers Joseph Boyden Three Day Road Viking Canada Golda Fried Nellcott Is My Darling Coach House Books Charlotte Gill Ladykiller Thomas Allen Publishers Kathy Page Alphabet McArthur & Company GovernorGeneralAward.xls Fiction Bibliothèque interculturelle 6767, -

A Writer-Centered World May 29Th to June 1St Delta St

2014 ONWORDS CONFERENCE AND ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING CENTERING THE MARGINS: A Writer-Centered World May 29th to June 1st Delta St. John’s 120 New Gower Street St. John’s, NL 2 2014 OnWords Conference and Annual General Meeting what’s INSIDE Agenda 04 Chair’s Report 10 Minutes, 2013 11 National Council & AGM Directives, 2013 21 Auditor’s Report 30 Forward, Together: Strategic Plan, 2010-2014 40 Regional Reports 41 Liaison, Task Force, and Committee Reports 46 Executive Director’s Welcome 69 Members and Guests Attending 70 Panelist and Speed Networker Biographies 71 Cover image © MUN, Department of Geography, 2013-80 May 29th – June 1st . Centering the Margins: A Writer-centered World 3 AGENDA Centering the Margins: A Writer-Centered World Hashtag for the weekend is: 2014 OnWords Conference and Annual General Meeting #OnWords Delta St. John’s Hotel and Conference Centre *Please remember to also add 120 New Gower Street, St. John’s, NL @twuc to your tweets as well May 29 – June 1, 2014 Thank to our lead sponsors the Access Copyright Foundation, ACTRA Fraternal Benefit Society, Amazon.ca, Random House of Canada, Mint Literary Agency, and Newfoundland Labrador. Please be aware that the use of spray colognes, hairsprays, and/or air fresheners, may trigger allergic reactions and create health problems for others. THURSDAY, May 29, 2014 2:00 pm – 3:00 pm EXECUTIVE MEETING — Placentia Bay room 3:00 pm – 5:00 pm NATIONAL COUNCIL MEETING — Placentia Bay room 4:00 pm – 6:00 pm REGISTRATION — Main Lobby 6:15 pm – 7:00 pm NEW MEMBER RECEPTION — Rocket Bakery and Fresh Foods, 272 Water Street 7:00 pm – 8:30 pm WELCOME RECEPTION WITH THE WRITERS ALLIANCE OF NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR — Rocket Bakery and Fresh Foods, 272 Water Street, 3rd floor. -

Longlisted & Shortlisted Books 1994-2018

Longlisted & Shortlisted Books 1994-2018 www.scotiabankgillerprize.ca # The Boys in the Trees, Mary Swan – 2008 13 Ways of Looking at a Fat Girl, Mona Awad - 2016 Brother, David Chariandy – 2017 419, Will Ferguson - 2012 Burridge Unbound, Alan Cumyn – 2000 By Gaslight, Steven Price – 2016 A A Beauty, Connie Gault – 2015 C A Complicated Kindness, Miriam Toews – 2004 Casino and Other Stories, Bonnie Burnard – 1994 A Fine Balance, Rohinton Mistry – 1995 Cataract City, Craig Davidson – 2013 The Age of Longing, Richard B. Wright – 1995 The Cat’s Table, Michael Ondaatje – 2011 A Good House, Bonnie Burnard – 1999 Caught, Lisa Moore – 2013 A Good Man, Guy Vanderhaeghe – 2011 The Cellist of Sarajevo, Steven Galloway – 2008 Alias Grace, Margaret Atwood – 1996 Cereus Blooms at Night, Shani Mootoo – 1997 Alligator, Lisa Moore – 2005 Childhood, André Alexis – 1998 All My Puny Sorrows, Miriam Toews – 2014 Cities of Refuge, Michael Helm – 2010 All That Matters, Wayson Choy – 2004 Clara Callan, Richard B. Wright – 2001 All True Not a Lie in it, Alix Hawley – 2015 Close to Hugh, Mariana Endicott - 2015 American Innovations, Rivka Galchen – 2014 Cockroach, Rawi Hage – 2008 Am I Disturbing You?, Anne Hébert, translated by The Colony of Unrequited Dreams, Wayne Johnston – Sheila Fischman – 1999 1998 Anil’s Ghost, Michael Ondaatje – 2000 The Colour of Lightning, Paulette Jiles – 2009 Annabel, Kathleen Winter – 2010 Conceit, Mary Novik – 2007 An Ocean of Minutes, Thea Lim – 2018 Confidence, Russell Smith – 2015 The Antagonist, Lynn Coady – 2011 Cool Water, Dianne Warren – 2010 The Architects Are Here, Michael Winter – 2007 The Crooked Maid, Dan Vyleta – 2013 A Recipe for Bees, Gail Anderson-Dargatz – 1998 The Cure for Death by Lightning, Gail Arvida, Samuel Archibald, translated by Donald Anderson-Dargatz – 1996 Winkler – 2015 Curiosity, Joan Thomas – 2010 A Secret Between Us, Daniel Poliquin, translated by The Custodian of Paradise, Wayne Johnston – 2006 Donald Winkler – 2007 The Assassin’s Song, M.G. -

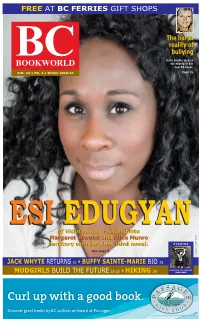

Esi Edugyan's

FREE AT BC FERRIES GIFT SHOPS TheThe harshharsh realityreality ofof BC bullying bullying Holly Dobbie tackles BOOKWORLD the misery in her new YA novel. VOL. 32 • NO. 4 • Winter 2018-19 PAGE 35 ESIESI EDUGYANEDUGYAN ofof VictoriaVictoria hashas rocketedrocketed intointo MargaretMargaret AtwoodAtwood andand AliceAlice MunroMunro PHOTO territoryterritory withwith justjust herher thirdthird novel.novel. STAMINA POPPITT See page 9 TAMARA JACK WHYTE RETURNS 10 • BUFFY SAINTE-MARIE BIO 25 PUBLICATION MAIL AGREEMENT BUILD THE FUTURE 22-23 • 26 MUDGIRLS HIKING #40010086 Curl up with a good book. Discover great books by BC authors on board at Passages. Orca Book Publishers strives to produce books that illuminate the experiences of all people. Our goal is to provide reading material that represents the diversity of human experience to readers of all ages. We aim to help young readers see themselves refl ected in the books they read. We are mindful of this in our selection of books and the authors that we work with. Providing young people with exposure to diversity through reading creates a more compassionate world. The World Around Us series 9781459820913 • $19.95 HC 9781459816176 • $19.95 HC 9781459820944 • $19.95 HC 9781459817845 • $19.95 HC “ambitious and heartfelt.” —kirkus reviews The World Around Us Series.com The World Around Us 2 BC BOOKWORLD WINTER 2018-2019 AROUNDBC TOPSELLERS* BCHelen Wilkes The Aging of Aquarius: Igniting Passion and Purpose as an Elder (New Society $17.99) Christine Stewart Treaty 6 Deixis (Talonbooks $18.95) Joshua -

The Translation of Anglo-Canadian Authors in Catalonia Isabel Alonso-Breto and Marta Ortega-Sáez

Made in Canada, Read in Spain: Essays on the Translation and Circulation of English-Canadian Literature Chapter 4 Canadian into Catalan: The Translation of Anglo-Canadian Authors in Catalonia Isabel Alonso-Breto and Marta Ortega-Sáez 1. Catalonia’s Singularity and Parallelisms with Quebec87 Although it may seem disconcerting to begin this chapter about the translation of Anglo-Canadian writers into Catalan with a comparison of Quebec and Catalonia in a book which only deals with CanLit in English, we find that the parallelism is apt because of the minority language and distinct nation status of these two constituencies, and because Quebec and English Canada are co- existent national entities, just like Catalonia and Spain. The parallelism between Catalonia and Quebec has recently been strengthened with the recent upsurge of nationalism and the demand for a referendum to decide whether to become separate from the Spanish state. The story is not new, since as a “historical” autonomous community with a language of its own, Catalan, and a distinct history88 and cultural tradition, often at odds with the Spanish ones, Catalonia presents some interesting parallelisms with Quebec, a province with its own language and cultural singularity, which sometimes are also in conflict with those of English Canada. Over the centuries, Catalan has acquired a strongly political added value, so much so that Catalan identity cannot be understood in isolation from commitment to the language. In fact, as regards language, parallelisms in the linguistic situations of Catalonia and Quebec cannot be overestimated. In Quebec, French has been the only official language since 1977. -

2 BC BOOKWORLD SUMMER 2013 3 BC BOOKWORLD SUMMER 2013 the Traditional Publishing Industry Is Broken Because the Gates Are Closed to Talented New Authors

2 BC BOOKWORLD SUMMER 2013 3 BC BOOKWORLD SUMMER 2013 The traditional publishing industry is broken Because the gates are closed to talented new authors Self-publishing never had a chance Because there is no quality control There has to be another way VIRTUES OF WAR Which isn’t all about the money 978-0-986672-20-0 WINNER – CYGNUS AWARD MILITARY SCIENCE FICTION Promontory Press is a new kind of publisher which offers the high quality, full distribution and sales support of traditional publishing, blended with the flexibility and author control of self-publishing. Created by authors for authors, Promontory recognizes that publishing is a busi- ness, but never forgets that writing is an art. STILLPOINT 978-1-927559-01-7 FINALIST – INDIE BOOK AWARD If you have a great book and GENERAL FICTION want a great shot at the market, contact us. AWARD-WINNERS PROMONTORY 2013 4 BC BOOKWORLD SUMMER 2013 BCTOP* SELLERS PEOPLE Standing Up with Ga'axsta'las: Jane Constance Cook & the Politics of Memory, Church, & Custom (UBC Press $39.95) by Leslie A. Robertson with the Kwagu'l Gixsam Clan Raven Brings the Light (Harbour $19.95) by Roy Henry Vickers & Robert Budd Indian Horse (D&M $21.95) by Richard Wagamese Little You (Orca Books $9.95) by Richard Van Camp & Julie Flett Allen Carr’s Easy Way to Stop Smoking (Sandhill Book Marketing $19.95) by Allen Carr Shoot! (New Star Books $19) by George Bowering He Moved a Mountain: The Life of Frank Calder and the Nisga’a Land Going overboard Claims Accord (Ronsdale Press $21.95) by Joan Harper “One of the things I have learned over the years is that in order to do what we do, we have to be immune to criticism.” – Paul Watson In 2012, Paul Watson became only the second person to receive France’s Jules Verne Award; the first was Jacques Cousteau. -

Rights Catalogue 2016

GOOSE LANE EDITIONS Rights Catalogue 2016 Goose Lane Editions T. 506.450.4251 | F. 506.459.4991 Toll Free: 1.888.926.8377 [email protected] www.gooselane.com FORTHCOMING ALOHA WANDERWELL NON-FICTION The Border-Smashing, Record-Setting Life of the Girl Who Stole the World CHRISTIAN FINK-JENSEN & RANDOLPH EUSTACE-WALDEN In 1922 an eighteen-year-old American woman set out to become the first female to drive around the world. Her name was Aloha Wanderwell. The project was foolhardy in the extreme. Drivable roads were scarce and the cars themselves — about as powerful as today’s ride-on mowers — were alien in much of the world. To overcome these limitations, the Wanderwell Expedition created a specially modified Model T Ford that featured rubber tires, steel disc wheels, gun scabbards, and a sloped back that could fold out to become a darkroom. Thus equipped, Aloha set out to see the world. All that remained was learning how to drive. Aloha’s name and adventures became known around the world. Tall, graceful, and beautiful, she was photographed in front of the Eiffel Tower, in the salt caverns of Poland, parked on the back of the Sphinx, firing mortars in China, visiting American fliers in Calcutta, meeting the prince regent of Japan, shaking hands with Mussolini, smiling through a tickertape parade in Detroit. She was an inspiration to thousands. As it turns out, the famous Aloha Wanderwell was an invention. The American Aloha Wanderwell was, in reality, the Canadian Idris Hall. And her mentor, the dashing filmmaker, lecturer, polyglot, and world traveller Captain Walter Wanderwell, was an invention himself. -

Jay Ruzesky Ing to Get Clean in Vancouver’S Thunder River by Tony Cosier (Thistledown $18.95) Downtown Eastside

PHOTO ROBSON PETER Reprinted thirteen times, Anne Cameron’s Daughters of Copper Woman is one of the bestselling books of fiction published from and about British Columbia. WINNER ANNEANNE CAMERONCAMERON Since 1995, BC BookWorld and the Vancouver Public Library have proudly sponsored the Woodcock Award and the Writers Walk at 350 West Georgia Street in Vancouver. 16TH ANNUAL GEORGE WOODCOCK LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARD FOR AN OUTSTANDING LITERARY CAREER IN BRITISH COLUMBIA ANNE CAMERON BIBLIOGRAPHY: Novels & Short Stories: Dahlia Cassidy (2004) • Family Resemblances (2003) • Hardscratch Row (2002) • Sarah's Children (2001) • Those Lancasters (2000) • Aftermath (1999) • Selkie (1996) • The Whole Dam Family (1995) • Deeyay and Betty (1994) • Wedding Cakes, Rats and Rodeo Queens (1994) • A Whole Brass Band (1992) • Kick the Can (1991) • Escape to Beulah (1990) • Bright's Crossing (1990) • South of an Unnamed Creek (1989) • Women, Kids & Huckleberry Wine (1989) • Tales of the Cairds (1989) • Stubby Amberchuk & The Holy Grail (1987) • Child of Her People (1987) • Dzelarhons: Mythology of the Northwest Coast (1986) • The Journey (1982) • Daughters of Copper Woman (1981) • Dreamspeaker (1979). Poetry: • The Annie Poems (1987) • Earth Witch (1983) Children's Books: T'aal: The One Who Takes Bad Children (1998) • The Gumboot Geese (1992) • Raven Goes Berrypicking (1991) • Raven & Snipe (1991) • Spider Woman (1988) • Lazy Boy (1988) • Orca's Song (1987) • Raven Returns the Water (1987) • How the Loon Lost her Voice (1985) • How Raven Freed the Moon -

Chimo 61 (Spring 2011)

Chimo The Newsjournal of the Canadian Association for Commonwealth Literature & Language Studies Number 61 Spring 2011 Chimo Spring 2011 Chimo (Chee’mo) greetings *Inuit+ Editor: Susan Gingell Book Reviews Editor: Margery Fee Chimo is published twice yearly by the Canadian Association for Commonwealth Literature and Language Studies. Please address editorial and business correspondence to Susan Gingell, Editor, Chimo, Department of English, University of Saskatchewan, 9 Campus Drive, Saskatoon, SK, Canada S7N 5A5 or [email protected]. Please address correspondence related to reviews to Margery Fee, Reviews Editor, Chimo, Department of English, University of British Columbia, #397-1873 East Mall, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z1 or [email protected]. The Editors appreciate receiving all extended submissions in electronic form (Microsoft Word, if possible). The Editors reserve the right to amend phrasing and punctuation in items accepted for publication in Chimo. Please address membership correspondence to Kristina Fagan, Secretary-Treasurer, CACLALS, Department of English, University of Saskatchewan, 9 Campus Drive, Saskatoon, SK, Canada S7N 5A5 or [email protected] On the cover: Three Birds, 2003, ink on paper, by Damon Badger Heit. Badger Heit holds a BA in Indian Art and English from the First Nations University of Canada, is a member of the Mistawasis First Nation, and resides in Regina. His art-making is education-based, and he has worked as an art instructor for youth programs in schools through organizations like the MacKenzie Art Gallery and Common Weal Inc., producing a number of public art works with youth at Regina's Connaught and Thompson Community Schools. Damon currently works as the Coordinator of First Nations and Métis Initiatives at SaskCulture Inc., a non-profit volunteer- driven organization that supports cultural activity throughout the province. -

Westwood 140764

Westwood Creative Artists ___________________________________________ FRANKFURT CATALOGUE Fall 2015 INTERNATIONAL RIGHTS Carolyn Forde AGENTS Carolyn Forde Jackie Kaiser Michael A. Levine Linda McKnight Hilary McMahon John Pearce Bruce Westwood FILM & TELEVISION Michael A. Levine 94 Harbord Street, Toronto, Ontario M5S 1G6 Canada Phone: (416) 964-3302 ext. 223 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.wcaltd.com October 2015 Westwood Creative Artists is looking forward to another phenomenal year of bringing exceptional writers and their works to an international audience. To that end, I would like to draw your attention to some of the outstanding accomplishments and developments that have taken place for our authors over the last few months: Clifford Jackman’s debut, The Winter Family, has been longlisted for the 2015 Scotiabank Giller Prize. Published by Doubleday in the US, Heyne in Germany and a “New Face of Fiction” for Random House Canada, The Winter Family was called “sadistic but mesmerizing” by The New York Times Book Review, a “chilling tale” by Publishers’ Weekly, and “a philosophical spaghetti western that doesn’t stint on the tomato sauce, served up with flair” by Quill & Quire. Reviewers have repeatedly put Jackman in the company of Cormac McCarthy and James Carlos Blake, and Amazon chose The Winter Family as a Best Mystery/Thriller/Suspense for the Month of April 2015. Chris Gerolmo, seven- time Academy Award nominated screenwriter of ‘Mississippi Burning’ is writing the film adaptation of The Winter Family. Giller Prize-winner Elizabeth Hay is back and at the top of her game with an irresistible new novel, His Whole Life.