Japan's Insurance Market

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 7. Building a Safe and Comfortable Society

Section 1 Realizing a Universal Society Building a Safe and Comfortable Chapter 7 Society Section 1 Realizing a Universal Society 1 Realizing Accessibility through a Universal Design Concept The “Act on Promotion of Smooth Transportation, etc. of Elderly Persons, Disabled Persons, etc.” embodies the universal design concept of “freedom and convenience for anywhere and anyone”, making it mandatory to comply with “Accessibility Standards” when newly establishing various facilities (passenger facilities, various vehicles, roads, off- street parking facilities, city parks, buildings, etc.), mandatory best effort for existing facilities as well as defining a development target for the end of FY2020 under the “Basic Policy on Accessibility” to promote accessibility. Also, in accordance with the local accessibility plan created by municipalities, focused and integrated promotion of accessibility is carried out in priority development district; to increase “caring for accessibility”, by deepening the national public’s understanding and seek cooperation for the promotion of accessibility, “accessibility workshops” are hosted in which you learn to assist as well as virtually experience being elderly, disabled, etc.; these efforts serve to accelerate II accessibility measures (sustained development in stages). Chapter 7 (1) Accessibility of Public Transportation In accordance with the “Act on Figure II-7-1-1 Current Accessibility of Public Transportation Promotion of Smooth Transportation, etc. (as of March 31, 2014) of Elderly Persons, Disabled -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents 1. Atmospheric data assimilation schemes, analysis and initialization, data impact studies, observing system experiments Author Paper Title Country Pages L. Duc, T. Koruda, K. Saito and Data assimilation experiments of Myanmar cyclone Japan 01-03 T. Fujita Nargis based on NHM-LETKF Radar reflectivity assimilation in JMA’s operational Y. Ikuta Japan 01-05 meso-analysis system Simplified basic state update in the JMA global 4D- T. Ishibashi Japan 01-07 Var A new inner model with a higher horizontal T. Kadowaki and K. Yoshimoto resolution (TL319) in JMA’s Global 4D-Var data Japan 01-09 assimilation system Assimilation experiments involving surface-sensitive M. Kazumori microwave radiances in JMA’s global data Japan 01-11 assimilation system Initial assessment of FY-3A microwave temperature M. Kazumori and H. Murata sounder radiance data in JMA’s global data Japan 01-13 assimilation system T. Kuroda, T. Fujita, H. Seko Construction of Mesoscale LETKF Data Assimilation Japan 01-15 and K. Saito Experiment System N. Saint-Ramond, A. Forecast sensitivity to observations at Météo-France Doerenbecher, F. Rabier, Application to GPS radio-occultation data France 01-17 V. Guidard, N. Fourrié GPS TPW Assimilation with the JMA Nonhydrostatic K. Saito, Y. Shoji, S. Origuchi, 4DVAR and Cloud Resolving Ensemble Forecast for Japan 01-19 L. Duc and H. Seko the 2008 August Tokyo Metropolitan Area Local Heavy Rainfalls H. Seko, S. Kogure and T. Observation System Simulation Experiments of Japan 01-21 Tsuda Quasi-Zenith Satellite H. Seko, K. Saito, O. Suzuki and Impacts of the low-level convergence data on the A. -

Tracking the Origin and Dispersion of Contaminated Sediments Transported by Rivers Draining the Fukushima Radioactive Contaminant Plume

Sediment Dynamics from the Summit to the Sea 237 (Proceedings of a symposium held in New Orleans, Louisiana, USA, 11–14 December 2014) (IAHS Publ. 367, 2014). Tracking the origin and dispersion of contaminated sediments transported by rivers draining the Fukushima radioactive contaminant plume HUGO LEPAGE1, OLIVIER EVRARD1, YUICHI ONDA2, CAROLINE CHARTIN1, IRENE LEFEVRE1, AYRAULT SOPHIE1 & PHILIPPE BONTE1 1 Laboratoire des Sciences du Climat et de l’Environnement (CEA, CNRS,UVSQ), F-91198 Gif-sur-Yvette France [email protected] 2 Center for Research in Isotopes and Environmental Dynamics (CRIED), Tsukuba University, Tsukuba, Japan Abstract This study was conducted in several catchments draining the main Fukushima Dai-ichi Power Plant contaminant plume in Fukushima prefecture, Japan. We collected soils and sediment drape deposits (n = 128) and investigated the variation in 137Cs enrichment during five sampling campaigns, conducted every six months, which typically occurred after intense erosive events such as typhoons and snowmelt. We show that upstream contaminated soils are eroded during summer typhoons (June–October) before being exported during the spring snowmelt (March–April). However, this seasonal cycle of sediment dispersion is further complicated by the occurrence of dam releases that may discharge large amounts of contaminants to the coastal plains during the coming years. Key words erosion; sediment; soil; Fukushima; radio-caesium; enrichment factor INTRODUCTION The Tohoku earthquake and the subsequent tsunami that occurred on 11 March 2011 impacted the Fukushima Dai-Ichi Nuclear Power Plant (FDNPP) and led to a significant atmospheric release of 137 radionuclides such as Cs (T1/2 = 30 years). About 80% of the release was transported out and over the Pacific Ocean, with the rest primarily deposited on the soils of Fukushima Prefecture as a result of wet atmospheric fallout. -

Sensitivity of Horizontal Resolution and Sea Spray to the Simulations

Sensitivity of horizontal resolution and sea spray to the simulations of Typhoon Roke in 2011 Akiyoshi Wada* *Meteorological Research Institute, Tsukuba, Ibaraki, 305-0052, JAPAN [email protected] 1. Introduction A previous report of Wada (2012) indicated that the horizontal resolution of 2 km was not enough to simulate the maximum intensity and structural change of Typhoon Roke in 2011 although the nonhydrostatic atmosphere model without ocean coupling well reproduced a rapid decrease in central pressure, 30 hPa in a day. In reality, a rapid intensification of Roke occurred when sea surface cooling was induced by the typhoon. This study addresses the sensitivity of horizontal resolution to the simulations of the typhoon. In addition, the sensitivity of an increase in turbulent heat fluxes due to the effect of sea spray induced by strong winds to the simulations was investigated in order to investigate the impact on the maximum intensity and intensification of simulated Roke. 2. Experimental design Summary of numerical simulations performed by Table 1 Summary of ocean coupling/noncoupling, horizontal resolution the atmosphere-wave-ocean coupled model (Wada et al., and sea spray parameterization Experiment Ocean Horizontal Sea spray 2010) is listed in Table1. The coupled model covered coupling resolution nearly a 1600 km x 1600 km computational domain with A2km NO 2 km - a horizontal grid spacing of 2 km in experiments A2km C2km YES 2 km - and C2km, and that of 1.5km in experiments C1.5km and CSP1.5km. The coupled model had 40 vertical levels C1.5km YES 1.5km - with variable intervals from 40 m for the near-surface CSP1.5km YES 1.5km Bao et al.(2000) layer to 1180 m for the uppermost layer. -

Development of and Studies with Coupled Ocean-Atmosphere Models

Section 9 Development of and studies with coupled ocean-atmosphere models Numerical simulations of the intensity change of Typhoon Choiwan (2009) and the oceanic response Akiyoshi Wada *Meteorological Research Institute, Tsukuba, Ibaraki, 305-0052, JAPAN [email protected] 1. Introduction Interactions between typhoons and the ocean are known to be important for predicting their intensity changes. In addition, a strong wind curl accompanied by typhoons induces sea surface cooling by passage of a TC, and causes variations in pCO2 in the upper ocean. The concentration of pCO2 is a function of the concentration of hydrogen ions, which is calculated by given water temperature, salinity, dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) and total alkalinity (ALK). Wada et al. (2011a, b) reported that a simple chemical scheme coupled with an ocean general circulation model (Wada et al., 2011a) or coupled with a nonhydrostatic atmosphere model coupled with a multilayer ocean model and the third generation ocean wave model enabled us to simulate variations in pCO2 and air-sea CO2 flux caused by Typhoons Tina and Winnie (1997) and Typhoon Hai-Tang (2005). However, the variations in pCO2 could not be validated for numerical simulations of Typhoon Hai-Tang (2005) due to lack of observation. Bond et al. (2011) reported that pCO2, the water minus air value, increased dramatically giving a maximum value of 55 atm and then it slowly decreases at the surface mooring buoy named the Kuroshio Extension Observatory (KEO) buoy by passage of Typhoon Choiwan in 2009. In order to clarify the mechanism of the variations in pCO2 in the upper ocean by passage of Choiwan, numerical simulations were performed using a nonhydrostatic atmosphere model coupled with the multilayer ocean model and the third generation ocean wave model. -

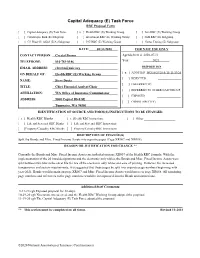

Capital Adequacy (E) Task Force RBC Proposal Form

Capital Adequacy (E) Task Force RBC Proposal Form [ ] Capital Adequacy (E) Task Force [ x ] Health RBC (E) Working Group [ ] Life RBC (E) Working Group [ ] Catastrophe Risk (E) Subgroup [ ] Investment RBC (E) Working Group [ ] SMI RBC (E) Subgroup [ ] C3 Phase II/ AG43 (E/A) Subgroup [ ] P/C RBC (E) Working Group [ ] Stress Testing (E) Subgroup DATE: 08/31/2020 FOR NAIC USE ONLY CONTACT PERSON: Crystal Brown Agenda Item # 2020-07-H TELEPHONE: 816-783-8146 Year 2021 EMAIL ADDRESS: [email protected] DISPOSITION [ x ] ADOPTED WG 10/29/20 & TF 11/19/20 ON BEHALF OF: Health RBC (E) Working Group [ ] REJECTED NAME: Steve Drutz [ ] DEFERRED TO TITLE: Chief Financial Analyst/Chair [ ] REFERRED TO OTHER NAIC GROUP AFFILIATION: WA Office of Insurance Commissioner [ ] EXPOSED ________________ ADDRESS: 5000 Capitol Blvd SE [ ] OTHER (SPECIFY) Tumwater, WA 98501 IDENTIFICATION OF SOURCE AND FORM(S)/INSTRUCTIONS TO BE CHANGED [ x ] Health RBC Blanks [ x ] Health RBC Instructions [ ] Other ___________________ [ ] Life and Fraternal RBC Blanks [ ] Life and Fraternal RBC Instructions [ ] Property/Casualty RBC Blanks [ ] Property/Casualty RBC Instructions DESCRIPTION OF CHANGE(S) Split the Bonds and Misc. Fixed Income Assets into separate pages (Page XR007 and XR008). REASON OR JUSTIFICATION FOR CHANGE ** Currently the Bonds and Misc. Fixed Income Assets are included on page XR007 of the Health RBC formula. With the implementation of the 20 bond designations and the electronic only tables, the Bonds and Misc. Fixed Income Assets were split between two tabs in the excel file for use of the electronic only tables and ease of printing. However, for increased transparency and system requirements, it is suggested that these pages be split into separate page numbers beginning with year-2021. -

NASA's TRMM Satellite Sees Typhoon Roke Intensify Rapidly Before Landfall in Japan 21 September 2011

NASA's TRMM Satellite sees Typhoon Roke intensify rapidly before landfall in Japan 21 September 2011 rainfall accumulation along the track of the storm. The image also showed significant rainfall accumulation (over 200 mm or ~8 inches) over the Japanese Island of Kyushu to the north of Typhoon Roke. This rain system continued to interact with Typhoon Roke in the subsequent 24 hours as Typhoon Roke continued moving north toward Japan's largest Island, Honshu. The second image Kelley created zooms into the inner core of Typhoon Roke during a period of rapid intensification, seen by the TRMM satellite at 1351 UTC (9:51 a.m. EDT) on September 19, 2011. This large-scale image provides context for the 3D radar data (in gray) by showing the three-day surface rainfall accumulation (rainbow colors) along the track of the storm (gray line). Also shown is the significant rainfall accumulation (over 200 mm or ~8 inches) over the Japanese Island of Kyushu to the north of Typhoon Roke. Credit: Credit: NASA/TRMM/Owen Kelley This image zooms into the inner core of Typhoon Roke The Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) during a period of rapid intensification, seen by the satellite captured rainfall and cloud data from TRMM satellite at 1351 UTC (9:51 a.m. EDT) on Sept. Typhoon Roke as it rapidly intensified before 19, 2011. The background is the cloud-top temperatures making landfall in Japan earlier today. (seen by TRMM infrared instrument). Dark gray indicates regions where This image shows shallow clouds (dark gray), clouds above freezing level (blue) and clouds that Typhoon Roke followed a looping path for five approach the tropopause (light-gray) indicating vigorous days while maintaining tropical-storm strength prior convection. -

Investigation on Effects of Initial Schemes for Binary Typhoons Roke and Sonca in 2011

Vol.22 S1 JOURNAL OF TROPICAL METEOROLOGY July 2016 Article ID: 1006-8775(2016) S1-0001-14 INVESTIGATION ON EFFECTS OF INITIAL SCHEMES FOR BINARY TYPHOONS ROKE AND SONCA IN 2011 1, 2 1 1 1 HUANG Yan-yan (黄燕燕) , CHEN Zi-tong (陈子通) , DAI Guang-feng (戴光丰) , ZHANG Cheng-zhong (张诚忠) , CHEN 2 Xun-lai (陈训来) (1. Guangzhou Institute of Tropical and Marine Meteorology/Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Regional Numerical Weather Prediction, CMA, Guangzhou 510080 China; 2. Shenzhen Key Laboratory of Severe Weather in South China, Shenzhen 518040 China) Abstract: Based on the Tropical Region Atmospheric Modeling System for South China Sea (TRAMS), Typhoon Roke (1115) and Sonca (1116) in 2011 which have large forecast errors in numerical operation prediction, have been selected for research focusing on the initial scheme and its influence on forecast. The purpose is to find a clue for model improvement and enhance the performance of the typhoon model. Several initialization schemes have been designed and the corresponding experiments have been done for Typhoon Roke and Sonca. The results show that the forecast error of both typhoons’ track and intensity are less using the initial scheme of relocation and bogus just for the weak Typhoon Sonca, compared with using the scheme for both typhoons. By analysis the influence of the scheme on weak typhoon vortex circulation may be the reason that leads to the improvement. All weak typhoons in 2011 to 2012 are selected for tests. It comes to the conclusion that the initial scheme of relocation and bogus can reduce the error of track and intensity forecast. -

Kitō Jiin in Contemporary Japanese Sōtō Zen Buddhism

Brands of Zen: Kitō jiin in Contemporary Japanese Sōtō Zen Buddhism Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Universität Heidelberg, vorgelegt von: Tim Graf, M.A. Erstgutachterin: Prof. Dr. Inken Prohl Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Harald Fuess Datum: 07.07.2017 Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 6 Research Questions and Goals for This Study ................................................................................ 7 A Theory of Religious Practice ......................................................................................................... 9 Towards a Working Definition of kitō ....................................................................................... 13 Material Religion ......................................................................................................................... 16 Religion and Marketing .............................................................................................................. 17 Methods ............................................................................................................................................ 19 Chapter Outlines ............................................................................................................................. 23 Chapter One: Historical Perspectives on ‘Zen’ and kitō ................................................................ -

Export of 134 Cs and 137 Cs in the Fukushima River Systems at Heavy Rains by Typhoon Roke in September 2011

Biogeosciences, 10, 6215–6223, 2013 Open Access www.biogeosciences.net/10/6215/2013/ doi:10.5194/bg-10-6215-2013 Biogeosciences © Author(s) 2013. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Export of 134 Cs and 137 Cs in the Fukushima river systems at heavy rains by Typhoon Roke in September 2011 S. Nagao1, M. Kanamori2, S. Ochiai1, S. Tomihara3, K. Fukushi4, and M. Yamamoto1 1Low Level Radioactivity Laboratory, Institute of Nature and Environmental Technology, Kanazawa University, Nomi, Ishikawa 923-1224, Japan 2Graduate School of Natural Science and Technology, Kanazawa University, Kakuma, Kanazawa, Ishikawa 920-1192, Japan 3Aquamarine Fukushima, Obama, Iwaki, Fukushima 971-8101, Japan 4Division of Earth Dynamics, Institute of Nature and Environmental Technology, Kanazawa University, Kakuma, Kanazawa, Ishikawa 920-1192, Japan Correspondence to: S. Nagao ([email protected]) Received: 31 December 2012 – Published in Biogeosciences Discuss.: 15 February 2013 Revised: 19 July 2013 – Accepted: 27 July 2013 – Published: 2 October 2013 Abstract. At stations on the Natsui River and the Same River gen explosions (Japanese Government, 2011; Chino et al., in Fukushima Prefecture, Japan, effects of a heavy rain event 2011). Surface deposition of 134Cs and 137Cs shows consid- on radiocesium export were studied after Typhoon Roke dur- erable external radioactivity in a zone extending northwest ing 21–22 September 2011, six months after the Fukushima from the NPP, about 20 km wide and 50–70 km long inside Dai-ichi Nuclear Power Plant accident. Radioactivity of the 80 km zone of the NPP (MEXT, 2011; Yoshida and Taka- 134Cs and 137Cs in river waters was 0.009–0.098 Bq L−1 in hashi, 2012). -

Schedule of Presentations and Abstracts: Updated May 21, 2012

Fourth International Workshop on Extratropical Transition (IWET4) Mont Gabriel Lodge St.-Adèle, Québec Canada May 20-25, 2012 Schedule of presentations and abstracts: Updated May 21, 2012 Monday, May 21: 0815: Welcome and Introduction 0830 Session 1 (ET Climatology) Chair: Shawn Milrad Kimberly M. Wood and Elizabeth A. Ritchie The University of Arizona Title: A 40-year climatology of extratropical transition in the eastern North Pacific. Part I: General characteristics. Extratropical transition has been frequently observed in many tropical basins around the world, including the western North Pacific, the northern Atlantic, and the southwestern Pacific. Conversely, only rare cases have been documented in the eastern North Pacific. This presentation will showcase a climatology of extratropical transition in this basin from 1970 to 2010, including cases which complete ET over open ocean and cases which begin ET but then make landfall before completing the process. This study utilizes 6-hourly reanalysis data from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts at a nominal resolution of 0.703 degrees from 1979 onward (ERA-Interim) and a nominal resolution of 1.125 degrees before 1979 (ERA-40) to produce cyclone phase space plots as well as examine the large-scale features present during extratropical transition in the eastern North Pacific. This presentation will also discuss the structure of ET in the eastern North Pacific. It will cover the average structural changes that occur during ET in this basin as well as explore how these changes differ from those seen elsewhere in the tropics. 0900 Elizabeth A. Ritchie and Kimberly M. Wood The University of Arizona Title: A 40-year climatology of extratropical transition in the eastern North Pacific. -

Analysis on Car Commuters' Behavior During a Massive Downpour Based on Probe Data and Questionnaire Survey

Journal of Japan Society of Civil Engineers, Ser. F3 (Civil Engineering Informatics), Vol. 72, No. 2, I_1-I_13, 2016. ANALYSIS ON CAR COMMUTERS’ BEHAVIOR DURING A MASSIVE DOWNPOUR BASED ON PROBE DATA AND QUESTIONNAIRE SURVEY Mohammad Hannan Mahmud KHAN1, Motohiro FUJITA2 and Wisinee WISETJINDAWAT3 1Student member of JSCE, Graduate Student, Dept. of Civil Eng., Nagoya Institute of Technology (Gokiso, Showa, Nagoya 466-8555, Japan) E-mail: [email protected] 2 Member of JSCE, Professor, Dept. of Civil Eng., Nagoya Institute of Technology (Gokiso, Showa, Nagoya 466-8555, Japan) E-mail: [email protected] 3 Member of JSCE, Assistant Prof., Dept. of Civil Eng., Nagoya Institute of Technology (Gokiso, Showa, Nagoya 466-8555, Japan) E-mail: [email protected] A massive downpour due to Typhoon Roke attacked the Tokai region on 20th September, 2011. Several roads in the northeastern part of Nagoya city and the adjacent areas were closed to traffic, resulting in a serious commuter chaos. In this research, we attempted to explore the effects of departure hours, early or late departure, the significance of acquiring proper traffic information as well as the impacts of road closures on the level of difficulty of home returning trips. Regression models were developed using both questionnaire survey and taxi probe data. Questionnaire survey can gather drivers’ information; however, it is difficult to gather the actual changes in travel condition. On the other hand, probe data can demonstrate a real time change in travel condition at every couple of minutes. Therefore, this study presents a combined usage of both data for a clearer explanation on the travel condition and the behavior of drivers during the typhoon.