Encoding of Bengali Khanda Ta in Unicode Peter Constable, Microsoft Corporation 2004-02-17

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Types of Polar Questions in Javanese Jozina VANDER KLOK 1

Types of polar questions in Javanese Jozina VANDER KLOK University of Oslo This paper describes the different grammatical strategies to form polar questions (broadly including yes-no questions and alternative questions) in Javanese, an area that has not been fully documented before. Focusing on the dialect of Javanese spoken in Paciran, Lamongan, East Java, Indonesia, yes-no questions can be formed with intonation, the particles opo, toh and iyo, or by fronting an auxiliary. Yes-no questions with narrow focus in this dialect are achieved via various syntactic positions of the particle toh in contrast to broad focus sentence- finally. Alternative questions are also formed with toh, either conjoining two constituents or with negation as a tag question. Based on these new findings in Paciran Javanese compared with Standard Javanese, the reflex of the alternative question particle is shown to co-vary with the disjunctive marker of that dialect. Additional dialectal variation concerning syntactic restrictions on auxiliary fronting is also discussed. Finally, combinations of these strategies— unexplored in any dialect—are shown to be possible (e.g., auxiliary fronting plus the particle opo) while other combinations are shown to be impossible (e.g., with the particle opo and particle toh in sentence final position). This paper serves as a benchmark for further investigation into dialectal variation across Javanese as well as into the syntax-semantics and syntax-prosody interfaces in deriving different types of yes-no questions. 1. Introduction1 Polar questions in Javanese—in any dialect—are currently not well-documented. Putting together descriptions from various sources on Standard Javanese, as spoken in the courtly centers of Yogyakarta and Surakarta/Solo, yes-no questions are noted to be formed via (i) intonation, (ii) the particle iya/yha/ya ‘yes’, (iii) the particle apa, and (iv) the particle ta (Horne 1961; Arps et al. -

Ka И @И Ka M Л @Л Ga Н @Н Ga M М @М Nga О @О Ca П

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3319R L2/07-295R 2007-09-11 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation Международная организация по стандартизации Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Proposal for encoding the Javanese script in the UCS Source: Michael Everson, SEI (Universal Scripts Project) Status: Individual Contribution Action: For consideration by JTC1/SC2/WG2 and UTC Replaces: N3292 Date: 2007-09-11 1. Introduction. The Javanese script, or aksara Jawa, is used for writing the Javanese language, the native language of one of the peoples of Java, known locally as basa Jawa. It is a descendent of the ancient Brahmi script of India, and so has many similarities with modern scripts of South Asia and Southeast Asia which are also members of that family. The Javanese script is also used for writing Sanskrit, Jawa Kuna (a kind of Sanskritized Javanese), and Kawi, as well as the Sundanese language, also spoken on the island of Java, and the Sasak language, spoken on the island of Lombok. Javanese script was in current use in Java until about 1945; in 1928 Bahasa Indonesia was made the national language of Indonesia and its influence eclipsed that of other languages and their scripts. Traditional Javanese texts are written on palm leaves; books of these bound together are called lontar, a word which derives from ron ‘leaf’ and tal ‘palm’. 2.1. Consonant letters. Consonants have an inherent -a vowel sound. Consonants combine with following consonants in the usual Brahmic fashion: the inherent vowel is “killed” by the PANGKON, and the follow- ing consonant is subjoined or postfixed, often with a change in shape: §£ ndha = § NA + @¿ PANGKON + £ DA-MAHAPRANA; üù n. -

M. Ricklefs an Inventory of the Javanese Manuscript Collection in the British Museum

M. Ricklefs An inventory of the Javanese manuscript collection in the British Museum In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde 125 (1969), no: 2, Leiden, 241-262 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/29/2021 11:29:04AM via free access AN INVENTORY OF THE JAVANESE MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION IN THE BRITISH MUSEUM* he collection of Javanese manuscripts in the British Museum, London, although small by comparison with collections in THolland and Indonesia, is nevertheless of considerable importance. The Crawfurd collection, forming the bulk of the manuscripts, provides a picture of the types of literature being written in Central Java in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, a period which Dr. Pigeaud has described as a Literary Renaissance.1 Because they were acquired by John Crawfurd during his residence as an official of the British administration on Java, 1811-1815, these manuscripts have a convenient terminus ad quem with regard to composition. A large number of the items are dated, a further convenience to the research worker, and the dates are seen to cluster in the four decades between AD 1775 and AD 1815. A number of the texts were originally obtained from Pakualam I, who was installed as an independent Prince by the British admini- stration. Some of the manuscripts are specifically said to have come from him (e.g. Add. 12281 and 12337), and a statement in a Leiden University Bah ad from the Pakualaman suggests many other volumes in Crawfurd's collection also derive from this source: Tuwan Mister [Crawfurd] asked to be instructed in adat law, with examples of the Javanese usage. -

Design of Javanese Text to Speech Application

Design of Javanese Text to Speech Application Yulia, Liliana, Rudy Adipranata, Gregorius Satia Budhi Informatics Department, Industrial Technology Faculty, Petra Christian University Surabaya, Indonesia [email protected] Abstract—Javanese is one of the many regional languages used in Indonesia. Javanese language is used by most of the population in Java. But now along with the development of the era, the use of regional languages including Javanese language is to be re- duced especially among the younger generation. One way to help conserve the use of Javanese language is to utilize information technologies, one of them is by developing a text to speech appli- cation that can be used to find out how the pronunciation of Ja- vanese language. In this paper, we discussed the design for Java- nese text to speech applications uses finite state automata. The design result will be used as rules to separate syllables when im- plementing text to speech application. Index Terms—Javanese language; Finite state automata; Text to speech. Figure 1: Basic Javanese characters I. INTRODUCTION In addition to the basic characters, the Javanese character Javanese language is a language widely spoken by the peo- has supplementary characters, consist of symbols for express- ple of Java. It is one of the regional languages of many region- ing vowels as well as a combination of two specific conso- al languages spoken in Indonesia. As one of the assets of na- nants. This supplementary characters is called sandhangan tional culture, Javanese language needs to be preserved. The and can be seen in Figure 2 [5]. younger generation is now more interested in learning a for- Symbol Example Read eign language, rather than the native Indonesian local lan- guage. -

Dissertation Information Service

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a manuscript sent to us for publication and microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to pho tograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. Pages in any manuscript may have indistinct print. In all cases the best available copy has been filmed. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. Manuscripts may not always be complete. When it is not possible to obtain missing pages, a note appears to indicate this. 2. When copyrighted materials are removed from the manuscript, a note ap pears to indicate this. 3. Oversize materials (maps, drawings, and charts) are photographed by sec tioning the original, beginning at the upper left hand comer and continu ing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is also filmed as one exposure and is available, for an additional charge, as a standard 35mm slide or m black and white paper format.* 4. Most photographs reproduce acceptably on positive microfilm or micro fiche but lack clarity on xerographic copies made from the microfilm. For an additional charge, all photographs are available in black and white standard 35mm slide format.* *For more information about black and white slides or enlarged paper reproductions, please contact the Dissertations Customer Services Department. Dissertation Information Service University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 N. Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48106 t 8618844 Saleh, Abdul Aziz DETERMINANTS OF ACCESS TO HIGHER EDUCATION IN INDONESIA The Ohio State University Ph.D. -

Old Javanese Legal Traditions in Pre-Colonial Bali

HELEN CREESE Old Javanese legal traditions in pre-colonial Bali Law codes with their origins in Indic-influenced Old Javanese knowledge sys- tems comprise an important genre in the Balinese textual record. Significant numbers of palm-leaf manuscripts, as well as later printed copies in Balinese script and romanized transliteration, are found in the major manuscript col- lections. A general overview of the Old Javanese legal corpus is included in Pigeaud’s four-volume catalogue of Javanese manuscripts, Literature of Java, under the heading ‘Juridical Literature’ (Pigeaud 1967:304-14, 1980:43), but detailed studies remain the exception. In spite of the considerable number of different legal treatises extant, and the insights they provide into pre-colonial judicial practices and forms of government, there have only been a handful of studies of Old Javanese and Balinese legal texts. A succession of nineteenth-century European visitors, ethnographers and administrators, notably Thomas Stamford Raffles (1817), John Crawfurd (1820), H.N. van den Broek (1854), Pierre Dubois,1 R. Friederich (1959), P.L. van Bloemen Waanders (1859), R. van Eck (1878-80) and Julius Jacobs (1883), routinely described legal practices in Bali, but European interest in Balinese legal texts was rarely philological. The first legal text to be published was a Dutch translation, without a word of commentary or explanation, of a section of the Dewadanda (Blokzeijl 1872). Then, in the early twentieth cen- tury, after the establishment of Dutch colonial rule over the entire island in 1908, Balinese (Djilantik and Oka 1909a, 1909b) and later Malay (Djlantik and Schwartz 1918a, 1918b, 1918c) translations of certain law codes were produced at the behest of Dutch officials who maintained that the Balinese priests who were required to administer adat law were unable to understand 1 Pierre Dubois,’Idée de Balie; Brieven over Balie’, [1833-1835], in: KITLV, H 281. -

Introduction to Old Javanese Language and Literature: a Kawi Prose Anthology

THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN CENTER FOR SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES THE MICHIGAN SERIES IN SOUTH AND SOUTHEAST ASIAN LANGUAGES AND LINGUISTICS Editorial Board Alton L. Becker John K. Musgrave George B. Simmons Thomas R. Trautmann, chm. Ann Arbor, Michigan INTRODUCTION TO OLD JAVANESE LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE: A KAWI PROSE ANTHOLOGY Mary S. Zurbuchen Ann Arbor Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies The University of Michigan 1976 The Michigan Series in South and Southeast Asian Languages and Linguistics, 3 Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/ Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 76-16235 International Standard Book Number: 0-89148-053-6 Copyright 1976 by Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies The University of Michigan Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-0-89148-053-2 (paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12818-1 (ebook) ISBN 978-0-472-90218-7 (open access) The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ I made my song a coat Covered with embroideries Out of old mythologies.... "A Coat" W. B. Yeats Languages are more to us than systems of thought transference. They are invisible garments that drape themselves about our spirit and give a predetermined form to all its symbolic expression. When the expression is of unusual significance, we call it literature. "Language and Literature" Edward Sapir Contents Preface IX Pronounciation Guide X Vowel Sandhi xi Illustration of Scripts xii Kawi--an Introduction Language ancf History 1 Language and Its Forms 3 Language and Systems of Meaning 6 The Texts 10 Short Readings 13 Sentences 14 Paragraphs.. -

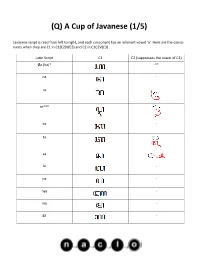

Q) a Cup of Javanese (1/5

(Q) A Cup of Javanese (1/5) Javanese script is read from left to right, and each consonant has an inherent vowel ‘a’. Here are the conso- nants when they are C1 in C1(C2)V(C3) and C2 in C1C2V(C3). Latin Script C1 C2 (suppresses the vowel of C1) Øa (ha)* -** na - ra re*** ka - ta sa la - pa - nya - ma - ga - (Q) A Cup of Javanese (2/5) Javanese script is read from left to right, and each consonant has an inherent vowel ‘a’. Here are the conso- nants when they are C1 in C1(C2)V(C3) and C2 in C1C2V(C3). Latin Script C1 C2 (suppresses the vowel of C1) ba nga - *The consonant is either ‘Ø’ (no consonant) or ‘h,’ but the problem contains only the former. **The ‘-’ means that the form exists, but not in this problem. ***The CV combination ‘re’ (historical remnant of /ɽ/) has its own special letters. ‘ng,’ ‘h,’ and ‘r’ must be C3 in (C1)(C2)VC3 before another C or at the end of a word. All other consonants after V must be C1 of the next syllable. If these consonants end a word, a ‘vowel suppressor’ must be added to suppress the inherent ‘a.’ Latin Script C3 -ng -h -r -C (vowel suppressor) Consonants can be modified to change the inherent vowel ‘a’ in C1(C2)V(C3). Latin Script V* e** (Q) A Cup of Javanese (3/5) Latin Script V* i é u o * If C2 is on the right side of C1, then ‘e,’ ‘i,’ and ‘u’ modify C2. -

Translation As Commentary in the Sanskrit-Old Javanese Didactic and Religious Literature from Java and Bali Andrea Acri and Thomas M

Translation as Commentary in the Sanskrit-Old Javanese Didactic and Religious Literature from Java and Bali Andrea Acri and Thomas M. Hunter* This article discusses the dynamics of translation and exegesis documented in the body of Sanskrit-Old Javanese Śaiva and Buddhist technical literature of the tutur/tattva genre, composed in Java and Bali in the period from c. the ninth to the sixteenth century. The texts belonging to this genre, mainly preserved on palm-leaf manuscripts from Bali, are concerned with the reconfiguration of Indic metaphysics, philosophy, and soteriology along localized lines. Here we focus on the texts that are built in the form of Sanskrit verses provided with Old Javanese prose exegesis – each unit forming a »translation dyad«. The Old Javanese prose parts document cases of linguistic and cultural »localization« that could be regarded as broadly corresponding to the Western categories of translation, paraphrase, and commen- tary, but which often do not fit neatly into any one category. Having introduced the »vyākhyā-style« form of commentary through examples drawn from the early inscriptional and didactic literature in Old Javanese, we present key instances of »cultural translations« as attested in texts composed at different times and in different geo- graphical and religio-cultural milieus, and describe their formal features. Our aim is to do- cument how local agents (re-)interpreted, fractured, and restated the messages conveyed by the Sanskrit verses in the light of their contingent contexts, agendas, and prevalent exegeti- cal practices. Our hypothesis is that local milieus of textual production underwent a pro- gressive »drift« from the Indic-derived scholastic traditions that inspired – and entered into a conversation with – the earliest sources, composed in Central Java in the early medieval period, and progressively shifted towards a more embedded mode of production in East Java and Bali from the eleventh to the sixteenth century and beyond. -

Information, Characters, Unicode

Information, Characters, Unicode Unicode © 24 August 2021 1 / 107 Hidden Moral Small mistakes can be catastrophic! Style Care about every character of your program. Tip: printf Care about every character in the program’s output. (Be reasonably tolerant and defensive about the input. “Fail early” and clearly.) Unicode © 24 August 2021 2 / 107 Imperative Thou shalt care about every Ěaracter in your program. Unicode © 24 August 2021 3 / 107 Imperative Thou shalt know every Ěaracter in the input. Thou shalt care about every Ěaracter in your output. Unicode © 24 August 2021 4 / 107 Information – Characters In modern computing, natural-language text is very important information. (“number-crunching” is less important.) Characters of text are represented in several different ways and a known character encoding is necessary to exchange text information. For many years an important encoding standard for characters has been US ASCII–a 7-bit encoding. Since 7 does not divide 32, the ubiquitous word size of computers, 8-bit encodings are more common. Very common is ISO 8859-1 aka “Latin-1,” and other 8-bit encodings of characters sets for languages other than English. Currently, a very large multi-lingual character repertoire known as Unicode is gaining importance. Unicode © 24 August 2021 5 / 107 US ASCII (7-bit), or bottom half of Latin1 NUL SOH STX ETX EOT ENQ ACK BEL BS HT LF VT FF CR SS SI DLE DC1 DC2 DC3 DC4 NAK SYN ETP CAN EM SUB ESC FS GS RS US !"#$%&’()*+,-./ 0123456789:;<=>? @ABCDEFGHIJKLMNO PQRSTUVWXYZ[\]^_ `abcdefghijklmno pqrstuvwxyz{|}~ DEL Unicode Character Sets © 24 August 2021 6 / 107 Control Characters Notice that the first twos rows are filled with so-called control characters. -

The Unicode Standard, Version 3.0, Issued by the Unicode Consor- Tium and Published by Addison-Wesley

The Unicode Standard Version 3.0 The Unicode Consortium ADDISON–WESLEY An Imprint of Addison Wesley Longman, Inc. Reading, Massachusetts · Harlow, England · Menlo Park, California Berkeley, California · Don Mills, Ontario · Sydney Bonn · Amsterdam · Tokyo · Mexico City Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and Addison-Wesley was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in initial capital letters. However, not all words in initial capital letters are trademark designations. The authors and publisher have taken care in preparation of this book, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode®, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. If these files have been purchased on computer-readable media, the sole remedy for any claim will be exchange of defective media within ninety days of receipt. Dai Kan-Wa Jiten used as the source of reference Kanji codes was written by Tetsuji Morohashi and published by Taishukan Shoten. ISBN 0-201-61633-5 Copyright © 1991-2000 by Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or other- wise, without the prior written permission of the publisher or Unicode, Inc. -

Mbok: Its Distribution, Meaning, and Function

MBOK: ITS DISTRIBUTION, MEANING, AND FUNCTION Ajar Pradika A. Tur Universitas Gadjah Mada Yogyakarta [email protected] Abstract: Mbok, in Javanese language, has not only a ’mother’ in meaning. As a lexicon in the language, mbok in one side truly means a ‘mother’ and still has the same meaning although it experiences the morphological process to be, at least, embok, simbok, or mboke. The variations exist and are spoken by Javanese native speakers throughout the Javanese dialects such as Suroboyoan, Solo, Yogyakarta, Bagelen, and Banyumasan dialects spread from the East Java, Yogyakarta, and Central Java. However, mbok, as a particle has different meaning, even different various meanings relying on its distribution in a sentence. Then the meanings bear its different various functions as well in the sentence based on the context of the sentence (grammatical-semantics meaning). Through Teknik Balik (Converse Technique) the data gained was analyzed to distinguish the position of the particle in the sentence in order to reach its significant different meanings and functions. At least, from the analysis, we have three positions of mbok in the sentences, that are in the initial, middle, and the end of the sentences. These positions affect the meanings and functions that can be seen as follows; ‘, is not it?’ (Tag Question) and ‘is/are” (Verbal Question) for emphasizing, ‘please’ for requesting a help, ‘may be’ and ‘in case’ for expressing possibility, and ‘causing’ for expressing cause-effect. Keywords: mbok, semantics, Banyumasan dialect Mbok, in the Javanese language, has a variety lexical meaning (Wedhawati et al., 2006:204). of meanings that do not merely mean ‘mother’.