9389/32 Paper 3 Interpretations Question October/November 2015 1 Hour Additional Materials: Answer Booklet/Paper *2289019987*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cambridge International Examinations Cambridge Ordinary Level

Cambridge International Examinations Cambridge Ordinary Level HISTORY 2158/13 Paper 1 World Affairs, 1917–1991 May/June 2014 2 hours 30 minutes Additional Materials: Answer Booklet/Paper *9722304068* READ THESE INSTRUCTIONS FIRST If you have been given an Answer Booklet, follow the instructions on the front cover of the Booklet. Write your Centre number, candidate number and name on all the work you hand in. Write in dark blue or black pen. You may use an HB pencil for any diagrams, graphs or rough working. Do not use staples, paper clips, glue or correction fluid. DO NOT WRITE IN ANY BARCODES. Answer five questions. Section A Answer at least one question from this Section. Sections B to F Answer questions from at least two of these Sections. All questions in this paper carry equal marks. The first part of each question is worth 14 marks and the last part is worth 6 marks. Answer each part of the questions chosen as fully as you can. At the end of the examination, fasten all your work securely together. This document consists of 7 printed pages and 1 blank page. DC (LK) 90309 © UCLES 2014 [Turn over 2 Section A International Relations and Developments 1 Describe how the Treaty of Versailles: (a) changed the European borders of Germany; (b) brought Germany’s colonial empire to an end. How far do you agree that Germany was not treated fairly by the terms of the Treaty of Versailles? 2 Describe the main features of: (a) Mussolini’s conquest of Abyssinia in 1935–36; (b) Hitler’s taking of Austria and Czechoslovakia in 1938–39. -

5849622628* Electronic Calculator

UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE INTERNATIONAL EXAMINATIONS General Certificate of Education Advanced Level THINKING SKILLS 9694/31 Paper 3 Problem Analysis and Solution May/June 2012 1 hour 30 minutes Additional Materials: Answer Booklet/Paper *5849622628* Electronic Calculator READ THESE INSTRUCTIONS FIRST If you have been given an Answer Booklet, follow the instructions on the front cover of the booklet. Write your Centre number, candidate number and name on all the work you hand in. Write in dark blue or black pen. Do not use staples, paper clips, highlighters, glue or correction fluid. DO NOT WRITE ON ANY BARCODES. Calculators should be used where appropriate. Answer all the questions. Start each question on a new answer sheet. At the end of the examination, fasten all your work securely together. The number of marks is given in brackets [ ] at the end of each question or part question. This document consists of 8 printed pages and 4 blank pages. IB12 06_9694_31/4RP © UCLES 2012 [Turn over 2 1 Study the information below and answer the questions. Show your working. The gold ducat is a coin currently worth 40 silver pennies, but, because of the scarcity of gold, King Offa is going to decree an increase in its value relative to the silver penny. Ethelred knows that this will be done overnight on one of the next four nights (Mon, Tue, Wed, Thu), and that the value will go up once by 1, 2, or 3 pennies. All possibilities are equally likely. Ethelred only has 30 silver pennies. He could get one or more overnight loans, but it costs a half penny to get a loan of 10 pennies from one day to the next. -

Appendix D: Important Facts About Alcohol and Drugs

APPENDICES APPENDIX D. IMPORTANT FACTS ABOUT ALCOHOL AND DRUGS Appendix D outlines important facts about the following substances: $ Alcohol $ Cocaine $ GHB (gamma-hydroxybutyric acid) $ Heroin $ Inhalants $ Ketamine $ LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide) $ Marijuana (Cannabis) $ MDMA (Ecstasy) $ Mescaline (Peyote) $ Methamphetamine $ Over-the-counter Cough/Cold Medicines (Dextromethorphan or DXM) $ PCP (Phencyclidine) $ Prescription Opioids $ Prescription Sedatives (Tranquilizers, Depressants) $ Prescription Stimulants $ Psilocybin $ Rohypnol® (Flunitrazepam) $ Salvia $ Steroids (Anabolic) $ Synthetic Cannabinoids (“K2”/”Spice”) $ Synthetic Cathinones (“Bath Salts”) PAGE | 53 Sources cited in this Appendix are: $ Drug Enforcement Administration’s Drug Facts Sheets1 $ Inhalant Addiction Treatment’s Dangers of Mixing Inhalants with Alcohol and Other Drugs2 $ National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism’s (NIAAA’s) Alcohol’s Effects on the Body3 $ National Institute on Drug Abuse’s (NIDA’s) Commonly Abused Drugs4 $ NIDA’s Treatment for Alcohol Problems: Finding and Getting Help5 $ National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Library of Medicine’s Alcohol Withdrawal6 $ Rohypnol® Abuse Treatment FAQs7 $ Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration’s (SAMHSA’s) Keeping Youth Drug Free8 $ SAMHSA’s Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality’s (CBHSQ’s) Results from the 2015 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables9 The substances that are considered controlled substances under the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) are divided into five schedules. An updated and complete list of the schedules is published annually in Title 21 Code of Federal Regulations (C.F.R.) §§ 1308.11 through 1308.15.10 Substances are placed in their respective schedules based on whether they have a currently accepted medical use in treatment in the United States, their relative abuse potential, and likelihood of causing dependence when abused. -

Impact of Drug Use on the Street Children 11

National Institute of Social Defence (NISD) A Trainer’s Manual on drug use prevention, treatment and care for street children A Trainer’s Manual on drug use prevention, treatment and care for street children National Institute of Social Defence (NISD) A Trainer’s Manual on Drug Use Prevention, Treatment and Care for Street Children Acknowledgments Acknowledgments We are grateful to Shri Chaitanya Murty- Director NISD, Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment, We are grateful to Shri Chaitanya Murty- Director NISD, Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment, Government of India, Ms. Cristina Albertin, Representative, UNODC, ROSA & Mr. Sunil Kumar, Government of India, Ms. Cristina Albertin, Representative, UNODC, ROSA & Mr. Sunil Kumar, Deputy Director, NCDAP-NISD, Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India for Deputy Director, NCDAP-NISD, Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, Government of India for their guidance and support. their guidance and support. Our sincere thanks to the authors: Our sincere thanks to the authors: Dr. Anju Dhawan- National Drug Dependence Treatment Centre, AIIMS Dr. Anju Dhawan- All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi Dr. Shekhar Sheshadri- NIMHANS Dr. Shekhar Sheshadri- National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences, Bangalore Ms. Rita Panicker- Butterflies Ms. Rita Panicker- Butterflies, New Delhi Dr. Koushik Sinha Deb- Department of Psychiatry and National Drug Dependence Treatment Centre, AIIMS Dr. Koushik Sinha Deb- All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi Dr. Prashanth.R- Department of Psychiatry and National Drug Dependence Treatment Centre, AIIMS Dr. Prashanth.R- All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi Mr. Raj Kumar Raju- Indian Harm Reduction Network Mr. -

Inhalant Abuse: a Volatile Research Agenda

National Institute on Drug Abuse RESEARCH MONOGRAPH SERIES Inhalant Abuse: A Volatile Research Agenda 129 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services • Public Health Service • National Institutes of Health Inhalant Abuse: A Volatile Research Agenda Editors: Charles Wm. Sharp, Ph.D. Fred Beauvais, Ph.D. Richard Spence, Ph.D. NIDA Research Monograph 129 1992 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Public Health Service National Institutes of Health National Institute on Drug Abuse 5600 Fishers Lane Rockville, MD 20857 ACKNOWLEDGMENT This monograph is based on the papers from a technical review on “Inhalant Abuse” held in 1989. The review meeting was sponsored by the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the Texas Commission on Alcohol and Drug Abuse. COPYRIGHT STATUS The National Institute on Drug Abuse has obtained permission from the copyright holders to reproduce certain previously published material as noted in the text. Further reproduction of this copyrighted material is permitted only as part of a reprinting of the entire publication or chapter. For any other use, the copyright holder’s permission is required. All other material in this volume except quoted passages from copyrighted sources is in the public domain and may be used or reproduced without permission from the Institute or the authors. Citation of the source is appreciated. Opinions expressed in this volume are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or official policy of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or any other part of the Department of Health and Human Services. The U.S. Government does not endorse or favor any specific commercial product or company. -

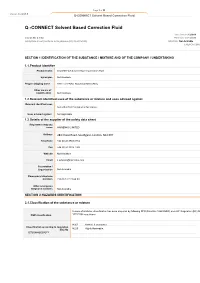

Q -CONNECT Solvent Based Correction Fluid

Page 1 of 11 Version No: 2.1.1.1 Q-CONNECT Solvent Based Correction Fluid Q -CONNECT Solvent Based Correction Fluid 3 Issue Date:01/12/2018 Version No: 2.1.1.2 Print Date: 01/12/2018 Safety Data Sheet (Conforms to Regulations (EC) No 2015/830) Initial Date: Not Available S.REACH.GBR.E SECTION 1 IDENTIFICATION OF THE SUBSTANCE / MIXTURE AND OF THE COMPANY / UNDERTAKING 1.1.Product Identifier Product name Q CONNECT Solvent Based Correction Fluid Synonyms Not Available Proper shipping name PAINT or PAINT RELATED MATERIAL Other means of identification Not Available 1.2.Relevant identified uses of the substance or mixture and uses advised against Relevant identified uses Correction fluid for paper or fax copies. Uses advised against Not Applicable 1.3.Details of the supplier of the safety data sheet Registered company name HAINENKO LIMITED Address 284 Chase Road, Southgate, London, N14 6HF Telephone +44 (0) 20 8882 8734 Fax +44 (0) 20 8882 7749 Website Not Available Email [email protected] Association / Organisation Not Available Emergency telephone numbers +33 (0) 3 27 23 64 00 Other emergency telephone numbers Not Available SECTION 2 HAZARDS IDENTIFICATION 2.1.Classification of the substance or mixture In case of mixtures, classification has been prepared by following DPD (Directive 1999/45/EC) and CLP Regulation (EC) No DSD classification 1272/2008 regulations H302 Harmful if swallowed. Classification according to regulation H225 Highly flammable. (EC) No 1272/2008 [CLP] [1]] Page 2 of 11 Version No: 2.1.1.1 Q-CONNECT Solvent Based Correction Fluid Flammable Liquid Category 2, Acute Toxicity (Oral) Category 4, Aspiration Hazard Category 1, Chronic Aquatic Hazard Category 2 Contains less than 0,1% benzene – (CLP) is applicable. -

Solvents/Inhalants Information for Health Professionals

Solvents/Inhalants Information for Health Professionals Introduction Inhalants compromise a wide variety of vapours, gases, and aerosols that can be inhaled to induce psychoactive (mind-altering) effects. Unlike other drugs, inhalants are available as legal products with low costs and wide availability. Examples include commercial products such as nail polish remover, hair sprays, lighter fluid, cleaning fluids, vegetable frying pan lubricants, and spray paints. These chemicals can be sniffed or inhaled because they are gaseous at room temperature and pressure. “Inhalant” is a general term that includes all substances used in this way. Most inhalants are volatile solvents, which are liquids that easily vaporize at room temperature and can contain many different chemicals that may be psychoactive. The majority of these solvents are produced from petroleum and natural gas. They have an enormous number of industrial, commercial and household uses, and are found in automobile fuels, cleaning fluids, toiletries, adhesives and fillers, paints, paint thinners, felt-tip markers, and many other products. In addition to volatile solvents, aerosols (hair spray, paint spray) can be abused as inhalants. Other inhalants include the nitrites (amyl and butyl, “poppers”, “Rush”) and gases such as the anesthetics nitrous oxide (laughing gas) and ether. Inhalants can be breathed in through the nose or mouth in a variety of ways, including spraying aerosols directly into the nose or mouth, “sniffing” or "snorting” fumes from containers, inhaling from balloons filled with nitrous oxide, “huffing” from an inhalant-soaked rag stuffed in the mouth, or “bagging”- pouring the substance over a cloth or into a plastic bag and breathing in the vapours. -

History 2158/01

UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE INTERNATIONAL EXAMINATIONS General Certificate of Education Ordinary Level HISTORY 2158/01 Paper 1 World Affairs since 1919 October/November 2006 2 hours 30 minutes Additional Materials: Answer Booklet/Paper READ THESE INSTRUCTIONS FIRST If you have been given an Answer Booklet, follow the instructions on the front cover of the Booklet. Write your Centre number, candidate number and name on all the work you hand in. Write in dark blue or black pen. You may use a soft pencil for any diagrams, graphs, or rough working. Do not use staples, paper clips, highlighters, glue or correction fluid. Answer five questions. Answer at least one question from Section A (General Problems) and questions from at least two of the other sections B to F. The first part of each question is worth two-thirds and the second part one-third of the marks. Answer each part of the questions chosen as fully as you can. At the end of the examination, fasten all your work securely together. All questions in this paper carry equal marks. This document consists of 7 printed pages and 1 blank page. SP (CW) S96205/2 © UCLES 2006 [Turn over www.OnlineExamHelp.com 2 Section A General Problems 1 Show how Germany’s status and power in Europe were affected by the terms of the following treaties: (a) Versailles (1919); (b) Locarno (1925). To what extent did the 1920s show an improvement in relations between Germany and other countries? 2 Describe the ways in which Mussolini increased his power in Italy during the years 1919–25. -

PDF Document

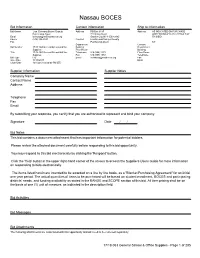

Nassau BOCES Bid Information Contact Information Ship to Information Bid Owner Lisa Schwartz Buyer / Deputy Address PO Box 9195 Address AS INDICATED ON PURCHASE Purchasing Agent 71 Clinton Road ORDERS ISSUED AS A RESULT OF Email [email protected] Garden City, NY 11530-9195 THIS BID Phone (516) 396-2231 Contact Lisa Schwartz/Buyer/Deputy Fax Purchasing Agent NY Department Contact Bid Number 17/18-063 General School & Office Building Department Supplies Floor/Room Building Title 17/18-063 General School & Office Telephone 516 (396) 2231 Floor/Room Supplies Fax 516 (997) 1053 Telephone Bid Type ITB Email [email protected] Fax Issue Date 11/15/2017 Email Close Date 12/7/2017 02:00:00 PM (ET) Supplier Information Supplier Notes Company Name Contact Name Address Telephone Fax Email By submitting your response, you certify that you are authorized to represent and bind your company. Signature Date / / Bid Notes This bid contains a document attachment that has important information for potential bidders. Please review the attached document carefully before responding to this bid opportunity. You may respond to this bid electronically by clicking the 'Respond' button. Click the 'Help' button in the upper right-hand corner of the screen to access the Suppliers Users Guide for more information on responding to bids electronically. The items listed herein are intended to be awarded on a line by line basis, as a "Blanket Purchasing Agreement" for an initial one year period. The actual quantities of items to be purchased will be based on student enrollment, BOCES and participating districts' needs, and funding availability as stated in the RANGE and SCOPE section of this bid. -

Abrdn Plc Small Estate Declaration and Indemnity Form

v1 07/21 For Administration Only REG OPS ROD Small Estate Declaration and Indemnity This form is to allow the Executor(s)/Next of Kin to transfer shares from a person who has passed away into their name(s) and provides information in regards to how the shares can be sold. Please note that completion of this form alone does not automatically sell the shares (see step 8). Please complete this form using block capitals and black ink. If you are not completing any of the boxes, please leave them blank. If you make a mistake cross it through and initial it. Please do not use correction fluid. Please read the Guidance Notes to ensure that the form is completed correctly which will avoid any delay in processing this request. Step 1 Please give the details of the deceased shareholder (see note 1). Shareholder’s name Last residing address and any previous known addresses* Company Shareholder Reference *If more space is needed, an accompanying letter is acceptable Step 2 Please give the details of all additional shareholdings (if applicable) Please use the enclosed additional holdings form to list all shareholdings administered by Equiniti. This is to ensure that this Small Estate Declaration and Indemnity covers them all. Step 3 All next of kin/executors should read the below Declaration To: Equiniti, Royal & Sun Alliance Insurance plc and the company named above and on the additional holdings form. I/We do solemnly and sincerely declare the following: - I am/We are the next of kin or executor(s) of the deceased as shown in the Last Will and Testament or foreign Grant of Representation and are entitled to administer the estate. -

Reach Annex Ii)

Staples - Correction Fluid 20ml and 25g Safety Data Sheet according to Regulation (EC) No. 453/2010 Date of issue: 12/03/2015 Revision date: 12/03/2015 : Version: 1.1 SECTION 1: Identification of the substance/mixture and of the company/undertaking 1.1. Product identifier Product form : Mixture Name : Staples - Correction Fluid 20ml and 25g Product code : CorrFluid 1.2. Relevant identified uses of the substance or mixture and uses advised against 1.2.1. Relevant identified uses Main use category : Consumer use,Professional use Use of the substance/mixture : Correction fluid 1.2.2. Uses advised against No additional information available 1.3. Details of the supplier of the safety data sheet Kores CE GmbH Muthgasse 36 1190 Vienna - Austria T +43 / 1 / 378 07 55 - F +43 / 1/ 318 55 77 [email protected] - www.kores.com 1.4. Emergency telephone number Emergency number : 112 (EU) Country Organisation/Company Address Emergency number IRELAND (REPUBLIC National Poisons Information Centre Beaumont Hospital Beaumont Road : +353 1 8379964 OF) Beaumont Hospital 9 Dublin UNITED KINGDOM National Poisons Information Service (NHS http://www.npis.org 111 (England & Wales only) Direct) or 112 (EU) or 08454 24 24 24 (Scotland) SECTION 2: Hazards identification 2.1. Classification of the substance or mixture Classification according to Regulation (EC) No. 1272/2008 [CLP] Flam. Liq. 2 H225 Aquatic Chronic 2 H411 Full text of H-phrases: see section 16 Classification according to Directive 67/548/EEC [DSD] or 1999/45/EC [DPD] F+; R12 R52/53 Full text of R-phrases: see section 16 Adverse physicochemical, human health and environmental effects No additional information available 2.2. -

UNIVERSITY of CAMBRIDGE INTERNATIONAL EXAMINATIONS General Certificate of Education Ordinary Level

UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE INTERNATIONAL EXAMINATIONS General Certificate of Education Ordinary Level HISTORY 2158/13 Paper 1 World Affairs, 1917–1991 May/June 2013 2 hours 30 minutes Additional Materials: Answer Booklet/Paper *4014360410* READ THESE INSTRUCTIONS FIRST If you have been given an Answer Booklet, follow the instructions on the front cover of the Booklet. Write your Centre number, candidate number and name on all the work you hand in. Write in dark blue or black pen. You may use a pencil for any diagrams, graphs or rough working. Do not use staples, paper clips, highlighters, glue or correction fluid. Answer five questions. Section A Answer at least one question from this Section. Sections B to F Answer questions from at least two of these Sections. All questions in this paper carry equal marks. The first part of each question is worth 14 marks and the last part is worth 6 marks. Answer each part of the questions chosen as fully as you can. At the end of the examination, fasten all your work securely together. This document consists of 8 printed pages. DC (SJF) 73165 © UCLES 2013 [Turn over 2 Section A International Relations and Developments 1 Show how each of the following countries was affected by the Paris peace settlement of 1919–20: (a) Czechoslovakia; (b) Poland; (c) Yugoslavia. Why did the settlement of 1919–20 cause problems in these countries? 2 Describe the arrangements made in 1919–20 for the administration under the League of Nations of the former colonies of: (a) the Ottoman Empire; (b) Germany.