Their Fellow-Men. Temptation by an Unseen Tempter, Is an Experience As Familiar to Every Spiritually-Observant Man, As Rescue by an Unseen Deliverer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

295 Emanuela Borgia (Rome) CILICIA and the ROMAN EMPIRE

EMANUELA BORGIA, CILICIA AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE STUDIA EUROPAEA GNESNENSIA 16/2017 ISSN 2082-5951 DOI 10.14746/seg.2017.16.15 Emanuela Borgia (Rome) CILICIA AND THE ROMAN EMPIRE: REFLECTIONS ON PROVINCIA CILICIA AND ITS ROMANISATION Abstract This paper aims at the study of the Roman province of Cilicia, whose formation process was quite long (from the 1st century BC to 72 AD) and complicated by various events. Firstly, it will focus on a more precise determination of the geographic limits of the region, which are not clear and quite ambiguous in the ancient sources. Secondly, the author will thoroughly analyze the formation of the province itself and its progressive Romanization. Finally, political organization of Cilicia within the Roman empire in its different forms throughout time will be taken into account. Key words Cilicia, provincia Cilicia, Roman empire, Romanization, client kings 295 STUDIA EUROPAEA GNESNENSIA 16/2017 · ROME AND THE PROVINCES Quos timuit superat, quos superavit amat (Rut. Nam., De Reditu suo, I, 72) This paper attempts a systematic approach to the study of the Roman province of Cilicia, whose formation process was quite long and characterized by a complicated sequence of historical and political events. The main question is formulated drawing on – though in a different geographic context – the words of G. Alföldy1: can we consider Cilicia a „typical” province of the Roman empire and how can we determine the peculiarities of this province? Moreover, always recalling a point emphasized by G. Alföldy, we have to take into account that, in order to understand the characteristics of a province, it is fundamental to appreciate its level of Romanization and its importance within the empire from the economic, political, military and cultural points of view2. -

Archaeology and History of Lydia from the Early Lydian Period to Late Antiquity (8Th Century B.C.-6Th Century A.D.)

Dokuz Eylül University – DEU The Research Center for the Archaeology of Western Anatolia – EKVAM Colloquia Anatolica et Aegaea Congressus internationales Smyrnenses IX Archaeology and history of Lydia from the early Lydian period to late antiquity (8th century B.C.-6th century A.D.). An international symposium May 17-18, 2017 / Izmir, Turkey ABSTRACTS Edited by Ergün Laflı Gülseren Kan Şahin Last Update: 21/04/2017. Izmir, May 2017 Websites: https://independent.academia.edu/TheLydiaSymposium https://www.researchgate.net/profile/The_Lydia_Symposium 1 This symposium has been dedicated to Roberto Gusmani (1935-2009) and Peter Herrmann (1927-2002) due to their pioneering works on the archaeology and history of ancient Lydia. Fig. 1: Map of Lydia and neighbouring areas in western Asia Minor (S. Patacı, 2017). 2 Table of contents Ergün Laflı, An introduction to Lydian studies: Editorial remarks to the abstract booklet of the Lydia Symposium....................................................................................................................................................8-9. Nihal Akıllı, Protohistorical excavations at Hastane Höyük in Akhisar………………………………10. Sedat Akkurnaz, New examples of Archaic architectural terracottas from Lydia………………………..11. Gülseren Alkış Yazıcı, Some remarks on the ancient religions of Lydia……………………………….12. Elif Alten, Revolt of Achaeus against Antiochus III the Great and the siege of Sardis, based on classical textual, epigraphic and numismatic evidence………………………………………………………………....13. Gaetano Arena, Heleis: A chief doctor in Roman Lydia…….……………………………………....14. Ilias N. Arnaoutoglou, Κοινὸν, συμβίωσις: Associations in Hellenistic and Roman Lydia……….……..15. Eirini Artemi, The role of Ephesus in the late antiquity from the period of Diocletian to A.D. 449, the “Robber Synod”.……………………………………………………………………….………...16. Natalia S. Astashova, Anatolian pottery from Panticapaeum…………………………………….17-18. Ayşegül Aykurt, Minoan presence in western Anatolia……………………………………………...19. -

Plinius Senior Naturalis Historia Liber V

PLINIUS SENIOR NATURALIS HISTORIA LIBER V 1 Africam Graeci Libyam appellavere et mare ante eam Libycum; Aegyptio finitur, nec alia pars terrarum pauciores recipit sinus, longe ab occidente litorum obliquo spatio. populorum eius oppidorumque nomina vel maxime sunt ineffabilia praeterquam ipsorum linguis, et alias castella ferme inhabitant. 2 Principio terrarum Mauretaniae appellantur, usque ad C. Caesarem Germanici filium regna, saevitia eius in duas divisae provincias. promunturium oceani extumum Ampelusia nominatur a Graecis. oppida fuere Lissa et Cottae ultra columnas Herculis, nunc est Tingi, quondam ab Antaeo conditum, postea a Claudio Caesare, cum coloniam faceret, appellatum Traducta Iulia. abest a Baelone oppido Baeticae proximo traiectu XXX. ab eo XXV in ora oceani colonia Augusti Iulia Constantia Zulil, regum dicioni exempta et iura in Baeticam petere iussa. ab ea XXXV colonia a Claudio Caesare facta Lixos, vel fabulosissime antiquis narrata: 3 ibi regia Antaei certamenque cum Hercule et Hesperidum horti. adfunditur autem aestuarium e mari flexuoso meatu, in quo dracones custodiae instar fuisse nunc interpretantur. amplectitur intra se insulam, quam solam e vicino tractu aliquanto excelsiore non tamen aestus maris inundant. exstat in ea et ara Herculis nec praeter oleastros aliud ex narrato illo aurifero nemore. 4 minus profecto mirentur portentosa Graeciae mendacia de his et amne Lixo prodita qui cogitent nostros nuperque paulo minus monstrifica quaedam de iisdem tradidisse, praevalidam hanc urbem maioremque Magna Carthagine, praeterea ex adverso eius sitam et prope inmenso tractu ab Tingi, quaeque alia Cornelius Nepos avidissime credidit. 5 ab Lixo XL in mediterraneo altera Augusta colonia est Babba, Iulia Campestris appellata, et tertia Banasa LXXV p., Valentia cognominata. -

The Turkish Conquest of Anatolia in the Eleventh Century

Hawliyat is the official peer-reviewed journal of the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences at the University of Balamand. It publishes articles from the field of Humanities. Journal Name: Hawliyat ISSN: 1684-6605 Title: The Turkish Conquest of Anatolia in the Eleventh Century Authors: S P O'Sullivan To cite this document: O’Sullivan, S. (2019). The Turkish Conquest of Anatolia in the Eleventh Century. Hawliyat, 8, 41-93. https://doi.org/10.31377/haw.v8i0.335 Permanent link to this document: DOI: https://doi.org/10.31377/haw.v8i0.335 Hawliyat uses the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-SA that lets you remix, transform, and build upon the material for non-commercial purposes. However, any derivative work must be licensed under the same license as the original. The Turkish Conquest of Anatolia in the Eleventh Century S.P. O'Sullivan Many historical events are part of common knowledge yet are understood only superficially even by specialists. Usually this is because the historical records are insufficient, something we would expect for remote and inconse quential events. But an event, neither remote nor at all unimportant. which remains obscure even in its broadest outlines would be cause for surprise. Such is the case for the conquest of Anatolia by the Turks. which took place during the late II th century. specially between 1071 and 1085. The Turkish con quest was important mainly because it spelt the end of the Greek presence in Asia. The Hellenic movement to the East eventually reached the borders of India and then slowly fell back in stages, each territorial loss inevitably followed by the extinguishing of Greek culture. -

Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-1992 Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance Leon Stratikis University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Modern Languages Commons Recommended Citation Stratikis, Leon, "Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 1992. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/2521 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Leon Stratikis entitled "Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Modern Foreign Languages. Paul Barrette, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: James E. Shelton, Patrick Brady, Bryant Creel, Thomas Heffernan Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation by Leon Stratikis entitled Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses A study of the client kings in the early Roman period Everatt, J. D. How to cite: Everatt, J. D. (1972) A study of the client kings in the early Roman period, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/10140/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk .UNIVERSITY OF DURHAM Department of Classics .A STUDY OF THE CLIENT KINSS IN THE EARLY ROMAN EMPIRE J_. D. EVERATT M.A. Thesis, 1972. M.A. Thesis Abstract. J. D. Everatt, B.A. Hatfield College. A Study of the Client Kings in the early Roman Empire When the city-state of Rome began to exert her influence throughout the Mediterranean, the ruling classes developed friendships and alliances with the rulers of the various kingdoms with whom contact was made. -

THE GEOGRAPHY of GALATIA Gal 1:2; Act 18:23; 1 Cor 16:1

CHAPTER 38 THE GEOGRAPHY OF GALATIA Gal 1:2; Act 18:23; 1 Cor 16:1 Mark Wilson KEY POINTS • Galatia is both a region and a province in central Asia Minor. • The main cities of north Galatia were settled by the Gauls in the third cen- tury bc. • The main cities of south Galatia were founded by the Greeks starting in the third century bc. • Galatia became a Roman province in 25 bc, and the Romans established colonies in many of its cities. • Pamphylia was part of Galatia in Paul’s day, so Perga and Attalia were cities in south Galatia. GALATIA AS A REGION and their families who migrated from Galatia is located in a basin in north-cen- Thrace in 278 bc. They had been invited tral Asia Minor that is largely flat and by Nicomedes I of Bithynia to serve as treeless. Within it are the headwaters of mercenaries in his army. The Galatians the Sangarius River (mode rn Sakarya) were notorious for their destructive and the middle course of the Halys River forays, and in 241 bc the Pergamenes led (modern Kızılırmak). The capital of the by Attalus I defeated them at the battle Hittite Empire—Hattusha (modern of the Caicus. The statue of the dying Boğazköy)—was in eastern Galatia near Gaul, one of antiquity’s most noted the later site of Tavium. The name Galatia works of art, commemorates that victo- derives from the twenty thousand Gauls ry. 1 The three Galatian tribes settled in 1 . For the motif of dying Gauls, see Brigitte Kahl, Galatians Re-imagined: Reading with the Eyes of the Vanquished (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2010), 77–127. -

Faith Tourism Potential of Konya in Terms of Christian Sacred Sites

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by European Scientific Journal (European Scientific Institute) European Scientific Journal July 2015 /SPECIAL/ edition ISSN: 1857 – 7881 (Print) e - ISSN 1857- 7431 FAITH TOURISM POTENTIAL OF KONYA IN TERMS OF CHRISTIAN SACRED SITES Dr. Gamze Temizel Dr. Melis Attar Selcuk University, Faculty of Tourism,Konya/Turkey Abstract Among the countries In the Middle East, Turkey is the second country that has the most biblical sites after Israel. It is called as ―The Other Holy Land‖ because of this reason. The land of Turkey which is bounded by the Mediterranean, Aegean, and Black Seas is referred as Asia Minor or Anatolia in Biblical reference works. Asia Minor or Anatolia as mentioned in history or the present day Turkey is important for Christianity to understand the background of the New Testament. Approximately two-thirds of New Testament books were written either to or from churches in Turkey. The three major apostles; Peter, Paul, and John either ministered or lived in Turkey. Turkey‘s rich spiritual heritage starts at the very beginning in the book of Genesis. Konya or Iconium as mentioned in history is one of the important cities of Turkey in terms of its historical and cultural heritage. It‘s a city that has an important place both in Christian and Islamic world, even in history and present day. Although Konya is famous today because of its Muslim mosques, its theological schools and its connection with the great Sufi mystic Celaleddin Rumi; better known as Mevlana, the 13th century Sufi mystic, poet, philosopher and founder of the Mevlevi order of whirling dervishes, Konya has a biblical significance since it was mentioned in the New Testament as one of the cities visited by Apostle Paul. -

The Global Paul

THE GLOBAL PAUL May 8-20, 2010 Damascus, Baalbeck, Antioch, Tarsus, Cappadocia, Derbe, Lystra, Psidian Antioch,The Laodicea, Hierapolis,Global Aphrodisias, Perga,Paul and Aspendos Cyprus Extension: May 20-22 MAIN TOUR: May 08 Sat Depart New York JFK – Fly Istanbul TK 002 depart at 16:45pm May 09 Sun Arrive Istanbul at 09:25. Take connecting flight to Damascus TK 952 departing at 2:35 pm. Arrive Damascus at 4:35 pm. Your tour guide will meet you with an “SBL” sign. Meet and transfer to your 5 star hotel for overnight. May 10 Mon Damascus This day is entirely dedicated to touring and discovering Damascus. We will explore the national museum of Damascus, the Omayyad mosque surrounded by old pagan temple walls, the straight street of Damascus, which is mentioned in the New Testament in reference to St. Paul, who recovered his sight & baptized in Damascus. Free time to stroll in the old bazaars of Damascus then head to Qasioun Mountain. Back to your hotel. (B,L,D) May 11 Tue Excursion Baalbeck - Damascus After breakfast, transfer to Baalbeck, Full day Baalbeck Sightseeing. Return to Damascus for overnight. (B,L,D) May 12 Wed Damascus – Turkey Border - Antioch Drive Turkish border.Transfer by taxis to hotel in Antioch.(B,L,D) May 13 Thu Antioch area & Seleucia Pieria. Overnight Adana. (B,L,D) May 14 Fri Adana Museum, Tarsus- Cappadocia. Overnight Cappadocia. (B,L,D) May 15 Sat Full day Cappadocia Visit the Cave Churches in Goreme, Zelve Valley, and Underground City. Overnight Cappadocia. (B,L,D) May 16 Sun Cappadocia-Derbe-Karaman Museum- Lystra - Iconium-Konya(B,L,D) May 17 Mon Pisidian Antioch-Yalvaç Museum-Laodicea-Hierapolis. -

Saul, Saul and Acts Exploring Who, Where and When in ACTS

Saul, Saul and Acts Exploring who, where and when in ACTS 3rd Journey Return to Jerusalem THE END for NOW Review Acts 20 – Offering to the poor saints at Jerusalem Macedonia (20:1) Greece (20:2) Macedonia (20:3-6) Where did Paul go? Paul went into Macedonia (those parts: Philippi, Thessalonica and Berea? Illyricum Rom 15:19) Came into Greece (Corinth, Cenchrea, Athens?) Organized a group to deliver an offering to the poor saints in Jerusalem (Rom 15:14-33) Whom did he meet? Them v.2 (Macedonian followers of Paul?) Those where he abode in Greece v. 3 Jews who laid wait for him (a good thing or a bad thing?) v.3 THOSE who were going to Jerusalem with him: Sopater of Berea Aristarchus and Secundus of Thessalonica Gaius and Timotheus of Derbe Tychicus and Trophimus of Asia (Ephesus)… EPH 6: 20-24 Luke from Philippi v.5,6 How long was he there? Time to go over Macedonia Three months in Greece (Corinth) 5 days in Philippi and 7 days in Troas (in ASIA) Macedonia (20:1) Greece (20:2) Macedonia (20:3-6) What did he say or preach? Much exhortation v. 2 He wrote the Book of Romans in verse 3 Acts 19:21 Plan to go to Rome (and Spain) via Jerusalem first 1 Cor 9:1-5 (Is this not Timothy and Erastus?) Rom 15:22-16:4 READ 16:1-5 Phebe delivers the letter to the Romans Looks like Priscilla and Aquila are back in Rome by Acts 20:3, and they have a house church: Rom 16:3-5 ONTO Jerusalem and Rome and Spain via Troas, Miletus, Tyre and Caesarea …. -

Biblical World

MAPS of the PAUL’SBIBLICAL MISSIONARY JOURNEYS WORLD MILAN VENICE ZAGREB ROMANIA BOSNA & BELGRADE BUCHAREST HERZEGOVINA CROATIA SAARAJEVO PISA SERBIA ANCONA ITALY Adriatic SeaMONTENEGRO PRISTINA Black Sea PODGORICA BULGARIA PESCARA KOSOVA SOFIA ROME SINOP SKOPJE Sinope EDIRNE Amastris Three Taverns FOGGIA MACEDONIA PONTUS SAMSUN Forum of Appius TIRANA Philippi ISTANBUL Amisos Neapolis TEKIRDAG AMASYA NAPLES Amphipolis Byzantium Hattusa Tyrrhenian Sea Thessalonica Amaseia ORDU Puteoli TARANTO Nicomedia SORRENTO Pella Apollonia Marmara Sea ALBANIA Nicaea Tavium BRINDISI Beroea Kyzikos SAPRI CANAKKALE BITHYNIA ANKARA Troy BURSA Troas MYSIA Dorylaion Gordion Larissa Aegean Sea Hadrianuthera Assos Pessinous T U R K E Y Adramytteum Cotiaeum GALATIA GREECE Mytilene Pergamon Aizanoi CATANZARO Thyatira CAPPADOCIA IZMIR ASIA PHRYGIA Prymnessus Delphi Chios Smyrna Philadelphia Mazaka Sardis PALERMO Ionian Sea Athens Antioch Pisidia MESSINA Nysa Hierapolis Rhegium Corinth Ephesus Apamea KONYA COMMOGENE Laodicea TRAPANI Olympia Mycenae Samos Tralles Iconium Aphrodisias Arsameia Epidaurus Sounion Colossae CATANIA Miletus Lystra Patmos CARIA SICILY Derbe ADANA GAZIANTEP Siracuse Sparta Halicarnassus ANTALYA Perge Tarsus Cnidus Cos LYCIA Attalia Side CILICIA Soli Korakesion Korykos Antioch Patara Mira Seleucia Rhodes Seleucia Malta Anemurion Pieria CRETE MALTA Knosos CYPRUS Salamis TUNISIA Fair Haven Paphos Kition Amathous SYRIA Kourion BEIRUT LEBANON PAUL’S MISSIONARY JOURNEYS DAMASCUS Prepared by Mediterranean Sea Sidon FIRST JOURNEY : Nazareth SECOND -

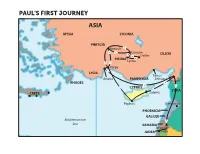

Paul's First Journey

PAUL’S FIRST JOURNEY ASIA MYSIA LYCONIA PHRYGIA Antioch Iconium CILICIA Derbe PISIDIA Lystra Perga LYCIA Tarsus Attalia PAMPHYLIA Seleucia Antioch RHODES CYPRUS SYRIA CRETE Salamis Paphos Damascus PHOENICIA GALILEE Mediterranean Sea SAMARIA Jerusalem JUDEA Gaza PAUL’S SECOND JOURNEY Neapolis Philippi BITHYNIA Amphipolis MACEDONIA Thessalonica CAPPADOCIA Berea Troas ASIA GALATIA GREECE Aegean MYSIA LYCAONIA ACHAIA Sea PHRYGIA Athens Corinth Ephesus Iconium Cenchreae Trogylliun PISIDIA Derbe CILICIA Lystra LYCIA PAMPHYLIA Antioch RHODES CYPRUS SYRIA CRETE Paphos PHOENICIA Mediterranean Sea GALILEE Caesarea SAMARIA Jerusalem JUDEA PAUL’S THIRD JOURNEY Philippi BITHYNIA MACEDONIA Thessalonica CAPPADOCIA Berea Aegean Troas ASIA GALATIA Assos GREECE Sea MYSIA LYCAONIA ACHAIA Chios Mitylene PHRYGIA Antioch Corinth Ephesus PISIDIA CILICIA Samos Miletus Colossae LYCIA Kos PAMPHYLIA Patara RHODES Antioch CYPRUS SYRIA CRETE PHOENICIA Tyre Mediterranean GALILEE Sea Ptolemais Caesarea SAMARIA Jerusalem JUDEA PAUL’S THIRD JOURNEY Philippi BITHYNIA MACEDONIA Thessalonica CAPPADOCIA Berea Aegean Troas ASIA GALATIA Assos GREECE Sea MYSIA LYCAONIA ACHAIA Chios Mitylene PHRYGIA Antioch Corinth Ephesus PISIDIA CILICIA Samos Miletus Colossae LYCIA Kos PAMPHYLIA Patara Antioch RHODES CYPRUS SYRIA CRETE PHOENICIA Tyre Mediterranean GALILEE Sea Ptolemais Caesarea SAMARIA Jerusalem JUDEA PAUL’S JOURNEY TO ROME DALMATIA Black Sea Adraitic THRACE ITALY Sea ROME MACEDONIA Three Taverns PONTUS Appii Forum Pompeii BITHYNIA Puteoli ASIA GREECE Agean Sea Tyrrhenian MYSIA Sea ACHAIA PHRYGIA CAPPADOCIA GALATIA LYCAONIA Ionian Sea PISIDIA SICILY Rhegium CILICIA Syracuse LYCIA PAMPHYLIA CRETE Myca RHODES MALTA SYRIA (MELITA) Clauda Fort CYPRUS Havens Mediterranean Sea PHOENICIA GALILEE Caesarea SAMARIA Antipatris CYRENAICA Jerusalem TRIPOLITANIA LIBYA JUDEA EGYPT.