Minnesota Statewide Multiple Property Documentation Form for the Woodland Tradition Section F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Many-Storied Place

A Many-storied Place Historic Resource Study Arkansas Post National Memorial, Arkansas Theodore Catton Principal Investigator Midwest Region National Park Service Omaha, Nebraska 2017 A Many-Storied Place Historic Resource Study Arkansas Post National Memorial, Arkansas Theodore Catton Principal Investigator 2017 Recommended: {){ Superintendent, Arkansas Post AihV'j Concurred: Associate Regional Director, Cultural Resources, Midwest Region Date Approved: Date Remove not the ancient landmark which thy fathers have set. Proverbs 22:28 Words spoken by Regional Director Elbert Cox Arkansas Post National Memorial dedication June 23, 1964 Table of Contents List of Figures vii Introduction 1 1 – Geography and the River 4 2 – The Site in Antiquity and Quapaw Ethnogenesis 38 3 – A French and Spanish Outpost in Colonial America 72 4 – Osotouy and the Changing Native World 115 5 – Arkansas Post from the Louisiana Purchase to the Trail of Tears 141 6 – The River Port from Arkansas Statehood to the Civil War 179 7 – The Village and Environs from Reconstruction to Recent Times 209 Conclusion 237 Appendices 241 1 – Cultural Resource Base Map: Eight exhibits from the Memorial Unit CLR (a) Pre-1673 / Pre-Contact Period Contributing Features (b) 1673-1803 / Colonial and Revolutionary Period Contributing Features (c) 1804-1855 / Settlement and Early Statehood Period Contributing Features (d) 1856-1865 / Civil War Period Contributing Features (e) 1866-1928 / Late 19th and Early 20th Century Period Contributing Features (f) 1929-1963 / Early 20th Century Period -

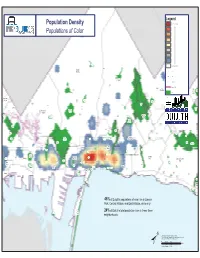

Population Density Populations of Color

Legend Legend Population Density Highest Population Density Populations of Color Sonside Park Lowest Population Density Duluth Heights School Æc Library Kenwood Hospital or Clinic Recreational Trail Rice Lake Park Woodland Athletic Lake Complex Park Annex Pleasant View Park Bayview Duluth Heights Community Heights Recreation Cntr Hartley Field Hartley Park Downer Park Janette Cody Pennel Park Pollay Arlington Park Piedmont Athletic Complex Morley Heights Hts/Parkview Oneota Park Piedmont Hunters Community Recreation Center Park Bagley Nature Area (UMD) Brewer Park Chester Park Bellevue Park Amity Park Amity Creek Park Enger Chester Quarry Municipal Copeland Lakeview Park Community Grant Community Park Golf Course Center Recreation Center Park-UMD Enger Hawk Park Ridge Hawk Ridge Nature Reserve Hilltop Park East Hillside Lincoln Congdon Park Old Park Main Cascade Park Park Portland Wheeler Square Athletic Washington Congdon Complex Central Com Rec Memorial Ctr Community Recreation Center Denfeld Hillside Park Lakeside-Lester Central Park Park Russell Midtown Civic Square Spirit Park Center Point of Rocks Park Valley Wade Sports Point of Complex Rocks Park Manchester Lincoln Square Lake Place Plaza Endion Leif Erickson Rose Garden Park Corner of Park the Lake CBD Park Lakewalk Washington East Square Irving Bayfront Park Oneota Grosvenor Square Lester/Amity Park Canal Park North Shore University Park Kitchi Gammi Park Franklin Park 46% of Duluth's populations of color live in Lincoln Park, Central Hillside, and East Hillside, while only Park 24% of Duluth's total population lives in these three Rice's Point Boat Landing Point neighborhoods. Data Source: Minnesota Population Center. National Historical Geographic Information System: Version 2.0 ± Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota 2011. -

Minnesota Statutes 2020, Chapter 85

1 MINNESOTA STATUTES 2020 85.011 CHAPTER 85 DIVISION OF PARKS AND RECREATION STATE PARKS, RECREATION AREAS, AND WAYSIDES 85.06 SCHOOLHOUSES IN CERTAIN STATE PARKS. 85.011 CONFIRMATION OF CREATION AND 85.20 VIOLATIONS OF RULES; LITTERING; PENALTIES. ESTABLISHMENT OF STATE PARKS, STATE 85.205 RECEPTACLES FOR RECYCLING. RECREATION AREAS, AND WAYSIDES. 85.21 STATE OPERATION OF PARK, MONUMENT, 85.0115 NOTICE OF ADDITIONS AND DELETIONS. RECREATION AREA AND WAYSIDE FACILITIES; 85.012 STATE PARKS. LICENSE NOT REQUIRED. 85.013 STATE RECREATION AREAS AND WAYSIDES. 85.22 STATE PARKS WORKING CAPITAL ACCOUNT. 85.014 PRIOR LAWS NOT ALTERED; REVISOR'S DUTIES. 85.23 COOPERATIVE LEASES OF AGRICULTURAL 85.0145 ACQUIRING LAND FOR FACILITIES. LANDS. 85.0146 CUYUNA COUNTRY STATE RECREATION AREA; 85.32 STATE WATER TRAILS. CITIZENS ADVISORY COUNCIL. 85.33 ST. CROIX WILD RIVER AREA; LIMITATIONS ON STATE TRAILS POWER BOATING. 85.015 STATE TRAILS. 85.34 FORT SNELLING LEASE. 85.0155 LAKE SUPERIOR WATER TRAIL. TRAIL PASSES 85.0156 MISSISSIPPI WHITEWATER TRAIL. 85.40 DEFINITIONS. 85.016 BICYCLE TRAIL PROGRAM. 85.41 CROSS-COUNTRY-SKI PASSES. 85.017 TRAIL REGISTRY. 85.42 USER FEE; VALIDITY. 85.018 TRAIL USE; VEHICLES REGULATED, RESTRICTED. 85.43 DISPOSITION OF RECEIPTS; PURPOSE. ADMINISTRATION 85.44 CROSS-COUNTRY-SKI TRAIL GRANT-IN-AID 85.019 LOCAL RECREATION GRANTS. PROGRAM. 85.021 ACQUIRING LAND; MINNESOTA VALLEY TRAIL. 85.45 PENALTIES. 85.04 ENFORCEMENT DIVISION EMPLOYEES. 85.46 HORSE -

A Bioarchaeological Study of a Prehistoric Michigan Population: Fraaer-Tyra Site (20Sa9) Allison June Muhammad Wayne State University

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations 1-1-2010 A Bioarchaeological Study Of A Prehistoric Michigan Population: Fraaer-Tyra Site (20sa9) Allison June Muhammad Wayne State University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the Organic Chemistry Commons, and the Other Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Muhammad, Allison June, "A Bioarchaeological Study Of A Prehistoric Michigan Population: Fraaer-Tyra Site (20sa9)" (2010). Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 50. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. A BIOARCHAEOLOGICAL STUDY OF A LATE WOODLAND POPULATION FROM MICHIGAN: FRAZER-TYRA SITE (20SA9) by ALLISON JUNE MUHAMMAD DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2010 MAJOR: ANTHROPOLOGY (Archaeology) Approved by: Advisor Date © COPYRIGHT BY ALLISON JUNE MUHAMMAD 2010 All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Bismillahi Rahmani Rahim Ashhadu alla ilaha illa-llahu wa Ashhadu anna Muhammadan abduhu wa rasuluh I would like to acknowledge my beautiful, energetic, loving daughters Bahirah, Laila, and Nadia. You have been my inspiration to complete this journey. I would also like to thank my family and friends for their kindness and their support. I would like to acknowledge the support and guidance of Dr. Mark Baskaran and Dr. Ed Van Hees of the WSU Geology department I would like to acknowledge the dedication and commitment of my dissertation committee to my success, particularly Dr. -

Minnesota Statutes 2020, Section 138.662

1 MINNESOTA STATUTES 2020 138.662 138.662 HISTORIC SITES. Subdivision 1. Named. Historic sites established and confirmed as historic sites together with the counties in which they are situated are listed in this section and shall be named as indicated in this section. Subd. 2. Alexander Ramsey House. Alexander Ramsey House; Ramsey County. History: 1965 c 779 s 3; 1967 c 54 s 4; 1971 c 362 s 1; 1973 c 316 s 4; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 3. Birch Coulee Battlefield. Birch Coulee Battlefield; Renville County. History: 1965 c 779 s 5; 1973 c 316 s 9; 1976 c 106 s 2,4; 1984 c 654 art 2 s 112; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 4. [Repealed, 2014 c 174 s 8] Subd. 5. [Repealed, 1996 c 452 s 40] Subd. 6. Camp Coldwater. Camp Coldwater; Hennepin County. History: 1965 c 779 s 7; 1973 c 225 s 1,2; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 7. Charles A. Lindbergh House. Charles A. Lindbergh House; Morrison County. History: 1965 c 779 s 5; 1969 c 956 s 1; 1971 c 688 s 2; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 8. Folsom House. Folsom House; Chisago County. History: 1969 c 894 s 5; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 9. Forest History Center. Forest History Center; Itasca County. History: 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. 10. Fort Renville. Fort Renville; Chippewa County. History: 1969 c 894 s 5; 1973 c 225 s 3; 1993 c 181 s 2,13 Subd. -

University of Michigan Radiocarbon Dates Xii H

[Ru)Ioc!RBo1, Vol.. 10, 1968, P. 61-114] UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN RADIOCARBON DATES XII H. R. CRANE and JAMES B. GRIFFIN The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan The following is a list of dates obtained since the compilation of List XI in December 1965. The method is essentially the same as de- scribed in that list. Two C02-CS2 Geiger counter systems were used. Equipment and counting techniques have been described elsewhere (Crane, 1961). Dates and estimates of error in this list follow the practice recommended by the International Radiocarbon Dating Conferences of 1962 and 1965, in that (a) dates are computed on the basis of the Libby half-life, 5570 yr, (b) A.D. 1950 is used as the zero of the age scale, and (c) the errors quoted are the standard deviations obtained from the numbers of counts only. In previous Michigan date lists up to and in- cluding VII, we have quoted errors at least twice as great as the statisti- cal errors of counting, to take account of other errors in the over-all process. If the reader wishes to obtain a standard deviation figure which will allow ample room for the many sources of error in the dating process, we suggest doubling the figures that are given in this list. We wish to acknowledge the help of Patricia Dahlstrom in pre- paring chemical samples and David M. Griffin and Linda B. Halsey in preparing the descriptions. I. GEOLOGIC SAMPLES 9240 ± 1000 M-1291. Hosterman's Pit, Pennsylvania 7290 B.C. Charcoal from Hosterman's Pit (40° 53' 34" N Lat, 77° 26' 22" W Long), Centre Co., Pennsylvania. -

Bipolar Technology and Pebble Stone Artifacts

Bipolar Technology and Pebble Stone Artifacts: Experimentation in Stone Tool Manufacture A thesis submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department ofAnthropology and Archaeology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan By Bruce David Low Fall 1997 ( Copyright Bruce David Low, 1997. All rights reserved.) PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereoffor financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head ofthe Department ofAnthropology and Archaeology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan (S7N 2AS) i ABSTRACT There is a general lack of research concerning the technological aspect of pebble stone artifacts throughout the Northern Plains. -

Indiana Archaeology

INDIANA ARCHAEOLOGY Volume 5 Number 2 2010/2011 Indiana Department of Natural Resources Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology (DHPA) ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Indiana Department of Natural Resources Robert E. Carter, Jr., Director and State Historic Preservation Officer Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology (DHPA) James A. Glass, Ph.D., Director and Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer DHPA Archaeology Staff James R. Jones III, Ph.D., State Archaeologist Amy L. Johnson Cathy L. Draeger-Williams Cathy A. Carson Wade T. Tharp Editors James R. Jones III, Ph.D., State Archaeologist Amy L. Johnson, Senior Archaeologist and Archaeology Outreach Coordinator Cathy A. Carson, Records Check Coordinator Publication Layout: Amy L. Johnson Additional acknowledgments: The editors wish to thank the authors of the submitted articles, as well as all of those who participated in, and contributed to, the archaeological projects which are highlighted. Cover design: The images which are featured on the cover are from several of the individual articles included in this journal. Mission Statement: The Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology promotes the conservation of Indiana’s cultural resources through public education efforts, financial incentives including several grant and tax credit programs, and the administration of state and federally mandated legislation. 2 For further information contact: Division of Historic Preservation and Archaeology 402 W. Washington Street, Room W274 Indianapolis, Indiana 46204-2739 Phone: 317/232-1646 Email: [email protected] www.IN.gov/dnr/historic 2010/2011 3 Indiana Archaeology Volume 5 Number 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Authors of articles were responsible for ensuring that proper permission for the use of any images in their articles was obtained. -

Hopewell Archeology: the Newsletter of Hopewell Archeology in the Ohio River Valley Volume 2, Number 2, October 1997

Hopewell Archeology: The Newsletter of Hopewell Archeology in the Ohio River Valley Volume 2, Number 2, October 1997 1. Current Research at Hopewell Culture National Historical Park By Bret J. Ruby, Hopewell Culture National Historical Park, Ohio Archeological research is an essential activity at Hopewell Culture National Historical Park. An active program of field research provides the information necessary to protect and preserve Hopewellian archeological resources. The program also addresses a series of long-standing questions regarding the cultural history and adaptive strategies of Hopewellian populations in the central Scioto region. Presented below are preliminary notices of recent field projects conducted by park personnel with the assistance of the National Park Service's Midwest Archeological Center, Lincoln, Nebraska. These recent efforts are focused on three Hopewellian centers in Ross County. Two of these centers, the Mound City Group and the Hopeton Earthworks, are administered by the National Park Service as units of Hopewell Culture National Historical Park. The third center, the Spruce Hill Works, is privately owned and is being considered for possible inclusion in the park. Research at the Mound City Group Work at the Mound City Group was prompted by plans to install a set of eight new interpretive signs along a trail encircling the mounds and earthworks at the site. Although the Mound City Group has been the focus of archeological investigations for almost 150 years, previous research has focused almost exclusively on the mounds and earthworks themselves (Figure 1), with little attention paid to identifying archeological resources that may lie just outside the earthwork walls. Figure 1. -

Guide to the Duluth Area Attractions

Guide to the Duluth Area Attractions Summer 2018 2018 Adventure Zone Family Fun Center 218-740-4000 / www.adventurezoneduluth.com SUMMER HOURS: Memorial Day - Labor Day Sunday - Thursday: 11am – 10pm Friday & Saturday 11am - Midnight WINTER HOURS: Monday – Thursday: 3 – 9pm Friday & Saturday: 11am – Midnight Sunday: 11am – 9pm DESCRIPTION: “Canal Park’s fun and games from A to Z”. There is something for everyone! The Northland’s newest family attraction boasts over 50,000 square feet of fun, featuring multi-level laser tag, batting cages, mini golf, the largest video/redemption arcade in the area, Vertical Endeavors rock climbing walls, virtual sports challenge, a kid’s playground and more! Make us your party headquarters! RATES: Laser Zone: Laser Tag $6 North Shore Nine: Mini Golf $4 Sport Plays: Batting Cages or Virtual Sports Simulator $1.75 per play or 3 plays for $5 DIRECTIONS: Located in Duluth’s Canal Park Business District at 329 Lake Avenue South, just blocks from Downtown Duluth and the famous Aerial Lift Bridge. DEALS: Adventure Zone offers many Daily Deals and Weekly Specials. A sample of those would include the Ultra Adventure Pass for $17, a Jr. Adventure Pass for $11, Monday Fun Day, Ten Buck Tuesday, Thursday Family Night and a Late Night Special on Fri & Sat for $10! AMENITIES: Meeting and Banquet spaces available with catering options from local restaurants. 2018 Bentleyville “Tour of Lights” 218-740-3535 / www.bentleyvilleusa.org WINTER HOURS: November 17 – December 26, 2018 Sunday – Thursday: 5 - 9pm Friday & Saturday: 5 – 10pm DESCRIPTION: A non-profit, charitable organization that holds a free annual family holiday light show – complete with Santa, holiday music and fire pits for roasting marshmallows. -

Prehistoric Settlements of Coastal Louisiana. William Grant Mcintire Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1954 Prehistoric Settlements of Coastal Louisiana. William Grant Mcintire Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Mcintire, William Grant, "Prehistoric Settlements of Coastal Louisiana." (1954). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 8099. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/8099 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HjEHisroaic smm&ws in coastal Louisiana A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Geography and Anthropology by William Grant MeIntire B. S., Brigham Young University, 195>G June, X9$k UMI Number: DP69477 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI DP69477 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest: ProQuest LLC. -

The Campground Host Volunteer Program

CAMPGROUND HOST PROGRAM THE CAMPGROUND HOST VOLUNTEER PROGRAM MINNESOTA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES 1 CAMPGROUND HOST PROGRAM DIVISION OF PARKS AND RECREATION Introduction This packet is designed to give you the information necessary to apply for a campground host position. Applications will be accepted all year but must be received at least 30 days in advance of the time you wish to serve as a host. Please send completed applications to the park manager for the park or forest campground in which you are interested. Addresses are listed at the back of this brochure. General questions and inquiries may be directed to: Campground Host Coordinator DNR-Parks and Recreation 500 Lafayette Road St. Paul, MN 55155-4039 651-259-5607 [email protected] Principal Duties and Responsibilities During the period from May to October, the volunteer serves as a "live in" host at a state park or state forest campground for at least a four-week period. The primary responsibility is to assist campers by answering questions and explaining campground rules in a cheerful and helpful manner. Campground Host volunteers should be familiar with state park and forest campground rules and should become familiar with local points of interest and the location where local services can be obtained. Volunteers perform light maintenance work around the campground such as litter pickup, sweeping, stocking supplies in toilet buildings and making emergency minor repairs when possible. Campground Host volunteers may be requested to assist in the naturalist program by posting and distributing schedules, publicizing programs or helping with programs. Volunteers will set an example by being model campers, practicing good housekeeping at all times in and around the host site, and by observing all rules.