Globalization and Language: English in Turkey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Felix Baumgartner & Red Bull Media

Issue No. 14 MediaTainmentFINANCEd Appreciate the Value to Business MIPCube fever is back For Decision-Makers and StrategistsmentMT; @JayKayMed Creativity Brings The second edition of the Who Value Creativity an Expendables producer in WWII drama future-of-TV event heats up www.mediatainmentfinance.com Head to Cannes Facebook: MediaTainment Finance; during MIPTV 8-11 April 2013 Twitter: @Mediatain or Tune into www.mipcube.com nvestors spin new Carmaggedon … 3-14 quin romances e-books NEWS Toast & Jam goes sweet on film ; film: Print mediaNitin Sawhneytune into TV;in direct-to-disc Goldman Sachs history sells 50% of CSI page 15 tv: UK tax relief delayed; I Qatar fund 3D printer escalates revolutionises stake in Tiffany’s home building music: Time Warner; Harle games: Stephen King’s novel digital campaign stuck right in the middle of fashion: dia collaborations architecture: India backs theme-park tourism books/prints:Europe’s Illegal richest to retransmit soccerPhotographer players live broadcastin censorship lawsuit country has spawned some of the world’s ads/marketing: sport: page 26 page 34 copyright: investors are lining up for Sports, a share brand … and me Europe’s biggest economy is live entertainment: r jumped from the edge of space and became photography/art: have denounced it as “the FEATURES & REPORTS Don’t turn your nose GERMANY: just text and be key to the never-ending fiscal euro crisis; but this of America’s most respected TV channels; biggest media empires, and foreign s its country of origin, Qatar, fit in? … MIPCube Feature: FELIX The USBAUMGARTNER Administration is said to &page 39 RED BULL MEDIA HOUSE flew to new heights when skydiver Baumgartne the first human to break the speed of sound in free fall; ngfind devices out how might Red hold Bull more and Red than Bull Media House used new technology to give him wings - literally .. -

Türkisch + Kurdisch + German 590 Channels

Türkisch + Kurdisch + German 590 Channels CNN Turk NTV Avrupa Planet Cocuk E2 Turk Shopping Turk Haberturk NTV Sport TV4 Turkey Mavi Karadeniz Med Nuce A Haber HD Sports Tv Eins Festival Kanal Tek Kurdistan S-Haber A Spor Travel Channel Turk Methab TV Knn News A Haber A Spor HD TGRT Belgesel Planet Turk Kurdsat Star Tv Turkiye FB Tv Yaban Tv Planet Mutfak Tishk TV Euro Star TGRT Kral TV Planet Pembe Rojhelat Fox Túrkye TGRT Haber Kral Pop Kanal C Speeda Kanal D Turkiye BRT 1 Köy Tv Maxi Tv Komala TV Euro D 365 Tv Power Turk Uzay Tv Newroz TV ATV Avrupa TRT 1 Nr 1 Turk MCJ Madiasa Shant TV ATV turkiye TRT Turk Gala Tv Yildiz Tv Gali Kurdistan ATV HD TRT Haber Viva Turkey Dost Tv Kanal 4 Kurd Show tv TRT Spor iMusic 1 Berat TV Korek TV Show Tv Turkey TRT Muzik Tatlises TV Sebil Tv Vin TV Show Turk HD TRT Belgesel Kanal T Irmak Tv NRT HD Samanyoulu Turkey TRT Cocuk Kanal S Ulusal Kanal Ronahi Kurdistan Samanyoulu TRT Avaz Tv 2000 Mmc Turk KurdMax TV8 TRT 6 EGE Tv Expo Channel Med Music TV8 Int TRT Diyanet Kon Tv HLT Flava Flash TV TRT HD Konya Tv Turk Hristiyan TV Bliss Bengu Turk TRT 1 HD Sivas SRT Kanal 5 Scuzz Cine5 Euro TRT Haber HD Turkmeneli Kanal 34 True Movies 1 Cine5 Turkiye Yamurack Tv Tek Rumeli TV Kanal 26 True Movies 2 Kanal 7 HD Cartoon Network Turkiye Ictimai TV Kanal 99 Tiny Pop Kanal 7 Avrupa Disney Turk Semerkend TV Avantaj tv Buz Muzik Tv2 Turk Karamel Semerkend HD Kanal B Tiny Pop +1 TV2 HD Kix Kids CCTV News GUNEYDOGU TV Pop Tv Halk Tv MinikaGo Gunaz Tv Dunya TV The Vault NTV Minika Cocuk CNBC-E Turk Sterk Tv PopGirl -

FEC Polarizasy on Kapsama V-Pid A-Pid Format Şifre A9 TV 6502 6602 S

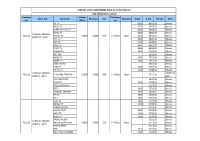

TÜRKSAT UYDU HABERLEŞME KALO TV ve İŞLETME A.Ş YENİ DÖENEM TV LİSTESİ Transpon Frekans Polarizasy Paket Adı Kanal Adı SR (ksps) FEC Kapsama V-pid A-pid Format Şifre der (MHz) on A9 TV 6502 6602 SD Şifresiz AKILLI TV 6503 6603 SD Şifresiz G.ANTEP OLAY TV 6501 6601 SD Şifresiz GENÇ TV 6500 6600 SD Şifresiz TÜRKSAT ANKARA T3A_01 HAYAT TV 12524 22500 '2/3' V - Dikey West 6504 6604 SD Şifresiz PAKET 15 - BATI HRT TV 6505 6605 SD Şifresiz IMC TV 6508 6608 SD Şifresiz LINE TV 6507 6607 SD Şifresiz TİVİTİ TV 6506 6606 SD Şifresiz ADANA TV 5403 5503 SD Şifresiz ART FM 5510 SD Şifresiz BARIŞ TV 5405 5505 SD Şifresiz BEDİR TV 5407 5507 SD Şifresiz CEM RADYO 5511 SD Şifresiz CEM TV 5401 5501 SD Şifresiz ÇİFTÇİ TV 5408 5508 SD Şifresiz TÜRKSAT ANKARA CRYPTOW T3A_01 ESKİŞEHİR STAR FM 12559 27500 '2/3' V - Dikey West 5512 SD PAKET 4 - BATI ORKS HAK MESAJ FM 5515 SD Şifresiz KOZA TV 5404 5504 SD Şifresiz POLİS RADYOSU 5513 SD Şifresiz SRT 1 5406 5506 SD Şifresiz TÜRKSAT TANITIM 5409 5509 SD Şifresiz TV 41 5400 5500 SD Şifresiz TV 5 5402 5502 SD Şifresiz 7/24 TV 5604 5704 SD Şifresiz DENGE TV 5608 5708 SD Şifresiz ERKAM RADYO 5714 SD Şifresiz KANAL FIRAT 5609 5709 SD Şifresiz MGC TV 5606 5706 SD Şifresiz OLAY TV 5601 5701 SD Şifresiz RADYO MÜZİK 5711 SD Şifresiz TÜRKSAT ANKARA T3A_02 RADYO SLOW TIME 12605 27500 '2/3' V - Dikey West 5712 SD Şifresiz PAKET 6 - BATI RADYO SPOR 5713 SD Şifresiz RTV 5610 5710 SD Şifresiz SHOPPING CHANNEL 5605 5705 SD Şifresiz TÜRKSAT ANKARA T3A_02 12605 27500 '2/3' V - Dikey West PAKET 6 - BATI TV 1 5603 5703 SD Şifresiz TV -

The Political Economy of the Media in Turkey: a Sectoral Analysis

TESEV Democratization Program Media Studies Series - 2 The Political Economy of the Media in Turkey: A Sectoral Analysis Ceren Sözeri Zeynep Güney DEMOCRATIZATION PROGRAM The Political Economy of the Media in Turkey: A Sectoral Analysis Ceren Sözeri Zeynep Güney The Political Economy of the Media in Turkey: A Sectoral Analysis Türkiye Ekonomik ve Bankalar Cad. Minerva Han Sosyal Etüdler Vakf› No: 2 Kat: 3 Turkish Economic and Karaköy 34420, İstanbul Social Studies Foundation Tel: +90 212 292 89 03 PBX Fax: +90 212 292 90 46 Demokratikleşme Program› [email protected] Democratization Program www.tesev.org.tr Authors: Production: Myra Ceren Sözeri Publication Identity Design: Rauf Kösemen Zeynep Güney Cover Design: Serhan Baykara Page Layout: Gülderen Rençber Erbaş Prepared for Publication by: Coordination: Sibel Doğan Esra Bakkalbaşıoğlu, Pre-print Coordination: Nergis Korkmaz Mehmet Ekinci Printed by: İmak Ofset Editing: Circulation: 500 copies Josee Lavoie TESEV PUBLICATIONS ISBN 978-605-5832-93-3 Copyright © September 2011 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced electronically or mechanically (photocopy, storage of records or information, etc.) without the permission of the Turkish Economic and Social Studies Foundation (TESEV). The viewpoints in this report belong to the authors, and they may not necessarily concur partially or wholly with TESEV’s viewpoints as a foundation. TESEV would like to extend its thanks to European Commission, Friedrich Ebert Stiftung Turkey, Open Society Foundation Turkey, and TESEV -

SPOR PROGRAMLARI ÖRNEĞİ Mustafa Kara 181153116

YENİ MEDYA TELEVİZYONCULUĞUNDA ETKİLEŞİM; SPOR PROGRAMLARI ÖRNEĞİ Mustafa Kara 181153116 DOKTORA TEZİ Disiplinlerarası İletişim Bilimleri Anabilim Dalı İletişim Bilimleri Doktora Programı Danışman: Prof. Dr. Celal Oktay Yalın İstanbul T.C. Maltepe Üniversitesi Lisansüstü Enstitüsü Şubat, 2021 YENİ MEDYA TELEVİZYONCULUĞUNDA ETKİLEŞİM: SPOR PROGRAMLARI ÖRNEĞİ Mustafa Kara 181153116 Orcid: 0000-0001-5696-1765 DOKTORA TEZİ Disiplinlerarası İletişim Bilimleri Anabilim Dalı İletişim Bilimleri Doktora Programı Danışman: Prof. Dr. C. Oktay Yalın İstanbul T.C. Maltepe Üniversitesi Lisansüstü Enstitüsü Şubat, 2021 JÜRİ VE ENSTİTÜ ONAYI Bu belge, Yükseköğretim Kurulu tarafından 19.01.2021 tarihli “Lisansüstü Tezlerin Elektronik Ortamda Toplanması, Düzenlenmesi ve Erişime Açılmasına İlişkin Yönerge” ile bildirilen 6689 Sayılı Kişisel Verilerin Korunması Kanunu kapsamında gizlenmiştir. ii ETİK İLKE VE KURALLARA UYUM BEYANI Bu belge, Yükseköğretim Kurulu tarafından 19.01.2021 tarihli “Lisansüstü Tezlerin Elektronik Ortamda Toplanması, Düzenlenmesi ve Erişime Açılmasına İlişkin Yönerge” ile bildirilen 6689 Sayılı Kişisel Verilerin Korunması Kanunu kapsamında gizlenmiştir. iii TEŞEKKÜR Doktora çalışmasına başlamamı her zaman teşvik eden, yüreklendiren , yönetim görevindeki tüm yoğunluğuna rağmen vakit ayıran ve izleme jürilerindeki kritik yönlendirmeleriyle yol gösteren değerli hocam, Rektörüm Prof. Dr. Şahin Karasar’a,Tez danışmanım olma nezaketini göstererek, çalışmamın geliştirilmesi ve sonuçlandırılmasındaki katkıları ve nezaketi ile yüreklendirici -

Belgesel Film

filmin ham malzemesinin özelliklerindendir İSTANBUL ÜNİVERSİTESİ AÇIK VE UZAKTAN EĞİTİM FAKÜLTESİ BELGESEL FİLM RADYO TELEVİZYON VE SİNEMA DR. ÖĞR. ÜYESİ ÖZLEM ARDA İSTANBUL ÜNİVERSİTESİ AÇIK VE UZAKTAN EĞİTİM FAKÜLTESİ İSTANBUL ÜNİVERSİTESİ AÇIK VE UZAKTAN EĞİTİM FAKÜLTESİ RADYO TELEVİZYON VE SİNEMA LİSANS PROGRAMI BELGESEL FİLM DR. ÖĞR. ÜYESİ ÖZLEM ARDA Yazar Notu Elinizdeki bu eser, İstanbul Üniversitesi Açık ve Uzaktan Eğitim Fakültesi’nde okutulmak için hazırlanmış bir ders notu niteliğindedir. ÖNSÖZ Belgesel film, sinemanın keşfiyle beraber üretimi başlayan bir film türüdür. Günümüze gelene kadar belgesel film şüphesiz değişim dönüşüm geçirmiştir; ancak değişmeyen ögesi her zaman gerçekliğin film dili ile anlatılması olmuştur. Belgesel sinemanın varlık sebebi insan ve insanların oluşturduğu toplumlardır. Belgesel film işte bu muazzam kaynaktan beslenir. I İÇİNDEKİLER ÖNSÖZ ........................................................................................................................... I İÇİNDEKİLER ............................................................................................................ II KISALTMALAR ......................................................................................................... X YAZAR NOTU ........................................................................................................... XI 1. BELGESEL FİLM TANIMI ................................................................................... 1 Bu Bölümde Neler Öğreneceğiz? .............................................................................. -

Turkish Television Serial Production Processes: Limitations on Creative Practices in the Digital Era

KADİR HAS UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES PROGRAM OF CINEMA AND TELEVISION TURKISH TELEVISION SERIAL PRODUCTION PROCESSES: LIMITATIONS ON CREATIVE PRACTICES IN THE DIGITAL ERA AYŞE YÖRÜKOĞLU SUPERVISORS: ASST. PROF. ELİF AKÇALI ASST. PROF. İREM İNCEOĞLU MASTER’S THESIS ISTANBUL, JULY, 2019 TURKISH TELEVISION SERIAL PRODUCTION PROCESSES: LIMITATIONS ON CREATIVE PRACTICES IN THE DIGITAL ERA AYŞE YÖRÜKOĞLU MASTER’S THESIS SubmItted to the School of Graduate Studies of Kadir Has UniversIty In partIal fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master’s in the Program of Cinema and TeleVIsIon ISTANBUL, AUGUST, 2019 DECLARATION OF RESEARCH ETHICS/ METHODSOF DISSEMINATION I, AYSE YORUKOGLJ,hereby declarethat; e this Master's Thesis is my own original work and that due references have been appropriately provided on all supporting literature and resources; e this Master’s Thesis contains no material that has been submitted or accepted for a degree or diploma in any other educational institution; eI have followed “Kadir Has University Academic Ethics Principles” prepared in accordance with the “The Council of Higher Education’s Ethical Conduct Principles” In addition, I understand that any false claim in respect of this work will result in disciplinary action in accordance with University regulations. Furthermore, both printed and electronic copies of my work will be kept in Kadir Has Information Center underthe following condition as indicated below: + The full content ofmy thesis/project will not be accessible for 6 months. Ifno extension is required by the end of this period, the full content of my thesis/project will be automatically accessible from everywhere by all means. -

Factors and Impacts in the Information Society a Prospective Analysis in the Candidate Countries Report on Turkey

FACTORS AND IMPACTS IN THE INFORMATION SOCIETY A PROSPECTIVE ANALYSIS IN THE CANDIDATE COUNTRIES REPORT ON TURKEY Serdar Sayan (Bilkent University) Sirin Elci and Hanzade Avci (Ankara Cyberpark) The authors of this report are solely responsible for the content, style, language and editorial control. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of the European Commission. April 2004 Technical Report EUR 21383 EN European Commission Joint Research Centre (DG JRC) Institute for Prospective Technological Studies http://www.jrc.es Legal notice Neither the European Commission nor any person acting on behalf of the Commission is responsible for the use which might be made of the following information. Technical Report EUR 21383 EN © European Communities, 2004 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Printed in Spain 2 FACTORS AND IMPACTS IN THE INFORMATION SOCIETY A PROSPECTIVE ANALYSIS IN THE CANDIDATE COUNTRIES Preface PREFACE The Institute for Prospective Technological Studies (IPTS) of the Directorate General Joint Research Centre of the European Commission contracted the International Centre for Economic Growth, European Centre (ICEG EC) to act as the coordinator of a consortium of 11 research institutes to carry out this project. The main objective of the project was to provide a series of national monographs studying the development of the Information Society (IS), including positive and negative impacts, in each of the candidate countries. These monographs offer an assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of each country regarding the development of IS (strongly rooted in factual quantitative data), and a view on their possible outcomes. They provide a clear, contextualised, multi-factoral and multi-causal picture of the input factors that contribute to the success or failure of IS developments, and the relevant output parameters that support mid- and long-term impacts on economic growth, employment and other relevant aspects of the future of each country. -

Türkiye | Media Ownership Monitor

MEDIA OWNERSHIP MONITOR TÜRKIYE SİYASET VE MEDYA TİCARİ ÇIKARLAR HÜKÜMET VE TV This is an automatically generated PDF version of the online resource turkey.mom-rsf.org/en/ retrieved on 2021/05/09 at 00:11 1 / 1131 Reporters Without Borders (RSF) & Bianet - all rights reserved, published under Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. MEDIA OWNERSHIP MONITOR TÜRKIYE Medya sahipliği önemlidir Kitle iletişim araçları, haberlerin toplum tarafından nasıl algılanacağı ve nasıl tartışılacağı üstündeki etkileri ile, kamuoyu oluşturmada rol oynar. Medyanın, fikirlerin ve görüşlerin bağımsız ve çoğulcu olması sağlıklı bir demokratik sistemin güvencesidir. Bu sistemde, iktidar odağı kişilere yönelik eleştiriler de serbestçe dile getirilebilmelidir. Özgür ve bağımsız tercihlerde bulunabilmenin ilk adımı, medyanın sahiplik yapısını izlemek ve bu sahipliğin çoğulculuğunu güvence altına almaktır: Kaynağı bilinmeyen bilginin güvenilirliği nasıl ölçülebilir? Gazeteciler, kimin kontrolünde olduğunu bilmedikleri bir medya kuruluşunda, nasıl hakkıyla çalışabilir? Medya otoriteleri, medya çarkının başında kimin olduğunu bilmeden, sektördeki aşırı güç yoğunlaşmasına nasıl çözüm üretebilirler? Sahiplik yapıları, medya endüstrisinin kaynak kullanımına da etki ederek, medya sektörünün ekonomik gücünü ve etkinliğini şekillendirebilir. Bu da, potansiyel yatırımcılar açısından özellikle önemli bir konudur. Medya ve Sahipleri MEDYA SAHİPLER This is an automatically generated PDF version of the online resource turkey.mom-rsf.org/en/ retrieved on 2021/05/09 at 00:11 2 / 1131 Reporters Without Borders (RSF) & Bianet - all rights reserved, published under Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. MEDIA OWNERSHIP MONITOR TÜRKIYE Bulgular El Koyulan Medya Siyasi İlişkiler Ticari Çıkarlar Türkiye hükümetinin muhalif En büyük 40 medya kuruluşuna En büyük 40 medya kuruluşuna medyayı tasfiye etme çabalarına sahip olan şirket ortaklarının çoğu sahip olan şirket ortaklarının çoğu yönelik eleştiriler AKP iktidarı iş insanları. -

Media Ownership and Financing in Turkey

MEDIA OWNERSHIP AND FINANCES IN TURKEY INCREASING CONCENTRATION AND CLIENTELISM by ASLI TUNÇ INTRODUCTION Turkey has a media atmosphere that revolves around many contradictions. At times it gives hope since it has a dynamic youth and a coterie of well-educat- ed and highly qualified journalists eager to do their profession against all odds. Yet, the other side of the coin is quite grim. Those journalists are trapped in a media system where the notion of integrity lacks on many levels. This research only emphasizes two indicators of media integrity: ownership and finances. It aims to provide some facts and figures leading the reader to comprehend a deeply dysfunctional media structure in the country. However, it has been al- most impossible to get access to basic financial data on the Turkish media mar- ket. Reliable secondary sources, previous reports and in-depth news analyses have been used due to this lack of transparency of media finances. Media sector is just a part of a bigger problem which is the consolidation of the judicial, exec- utive, and legislative branch. In such an environment, the media, ideally as the fourth estate, cannot serve public interest and fulfill its democratic functions. At a glance, the Turkish media scene seems to be quite diverse since there are approximately 3,100 newspapers circulating in Turkey, including some 180 national papers.1 The total circulation of national daily newspapers is 4,304,906 copies in a country with a population of 77.6 million. The broadcasting scene also seems diverse. According to the 2014 data of the Radio and Television Supreme Council (RTÜK), there are 23 national, 17 regional and 205 local television sta- tions, and 38 national, 100 regional and 921 local radio channels in the country. -

Futbol Ekonomisi: Avrupa Ve Türkiye Üzerine Karşılaştırmalı Bir Inceleme

T.C. İSTANBUL ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ İKTİSAT ANABİLİM DALI İKTİSAT POLİTİKASI BİLİM DALI YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ FUTBOL EKONOMİSİ: AVRUPA VE TÜRKİYE ÜZERİNE KARŞILAŞTIRMALI BİR İNCELEME Uygar Delal ÇAKMAK 2501120296 TEZ DANIŞMANI Prof. Dr. Cem SAATÇİOĞLU İSTANBUL – 2019 ÖZ FUTBOL EKONOMİSİ: AVRUPA VE TÜRKİYE ÜZERİNE KARŞILAŞTIRMALI BİR İNCELEME UYGAR DELAL ÇAKMAK Futbol, günümüzde, milyonlarca dolarlık yayın gelirleri, sponsorluk ve reklam anlaşmaları, maç günü gelirleri, futbolcu sözleşmeleri ve etkileşimde bulunduğu yan sektörler ile endüstriyel bir iş koluna dönüşmüş durumdadır. Futbolun boş zaman etkinliğinden ticari bir faaliyete dönüşmesinde profesyonellik, ücret serbestisi, sponsorluk ve reklam anlaşmaları etkili olmuştur. Ancak, futbolun yapısını 1980’li yıllardan sonra yayın alanında yaşanan atılımlar kökten değiştirmiştir. Medya şirketlerinin futbolun reytinginden kar sağlamak için liglerin yayın haklarını satın alması, her sektörden şirketin de futbolun popülaritesinden yararlanmak için kulüplere sponsor olmaları futbol ekonomisinin gelirlerini artırmıştır. Sponsorluk ve yayın gelirleri ile ticarileşen futbolda, aynı dönemde giderler de yüksek oranda artmıştır. Giderlerdeki artışta 1995 yılında getirilen ve futbolcuların hareket özgürlüğünü artıran Bosman Kararları’nın payı büyüktür. Günümüzde, futbol kulüplerinin giderlerinin önemli bölümü ücret giderlerinden oluşmakta, ayrıca, kulüpler oyuncu transferlerine milyonlarca dolar harcamaktadır. Yeni futbol ekonomisi ile gelir-gider dengesini kontrol etmekte zorlanan -

Behavioral Changes of the Audience by the Algorithmic Recommendation Systems Inside Video-On-Demand

CANGÜRMERİÇ BEHAVIORAL CHANGES OF THE AUDIENCE BY THE ALGORITHMIC RECOMMENDATION SYSTEMS INSIDE VIDEO-ON-DEMAND PLATFORMS CONSIDERING THE EXAMPLE OF NETFLIX BEHAVIORAL CHANGES OF THE AUDIENCE THE CHANGESOF BEHAVIORAL A Master’s Thesis RECOMMENDATION SYSTEMS INSIDE VIDEO INSIDE SYSTEMS RECOMMENDATION PLATFORMS by CAN GÜRMERIÇ CONSIDERING THE EXAMPLE OF NETFLIX EXAMPLE THE CONSIDERING OF Department of Communication and Design BY THE ALGORITHMIC THE BY İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University Ankara - ON May 2019 - DEMAND Bilkent2019 University To Can Gürmeriç (Her Şey Çok Güzel Olacak) iii BEHAVIORAL CHANGES OF THE AUDIENCE BY THE ALGORITHMIC RECOMMENDATION SYSTEMS INSIDE VIDEO-ON-DEMAND PLATFORMS CONSIDERİNG THE EXAMPLE OF NETFLIX The Graduate Schools of Economics and Social Sciences of İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University by CAN GÜRMERIÇ In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN MEDIA AND VISUAL STUDIES THE DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATION and DESIGN İHSAN DOĞRAMACI BİLKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA May 2019 iv ABSTRACT BEHAVIORAL CHANGES OF THE AUDIENCE BY THE ALGORITHMIC RECOMMENDATION SYSTEMS INSIDE VIDEO-ON-DEMAND PLATFORMS CONSIDERİNG THE EXAMPLE OF NETFLIX Gürmeriç, Can M. A., Department of Communication and Design Supervisor: Asst. Prof. Dr. Lutz Peschke May 2019 Digital media revolution has provided new possibilities for different industries globally, in lives of individuals including business related areas, entertainment and personal relations. Technological advancements have sped up these changes, especially with the Internet and computational devices. Convergence of the Internet and existing media elements like telephones and computers have altered media, society and the culture of 21st Century. Traditional media forms like television has started to be affected by these changes as well.