Some Problems from Kayardild

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Romani Syntactic Typology Evangelia Adamou, Yaron Matras

Romani Syntactic Typology Evangelia Adamou, Yaron Matras To cite this version: Evangelia Adamou, Yaron Matras. Romani Syntactic Typology. Yaron Matras; Anton Tenser. The Palgrave Handbook of Romani Language and Linguistics, Springer, pp.187-227, 2020, 978-3-030-28104- 5. 10.1007/978-3-030-28105-2_7. halshs-02965238 HAL Id: halshs-02965238 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02965238 Submitted on 13 Oct 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Romani syntactic typology Evangelia Adamou and Yaron Matras 1. State of the art This chapter presents an overview of the principal syntactic-typological features of Romani dialects. It draws on the discussion in Matras (2002, chapter 7) while taking into consideration more recent studies. In particular, we draw on the wealth of morpho- syntactic data that have since become available via the Romani Morpho-Syntax (RMS) database.1 The RMS data are based on responses to the Romani Morpho-Syntax questionnaire recorded from Romani speaking communities across Europe and beyond. We try to take into account a representative sample. We also take into consideration data from free-speech recordings available in the RMS database and the Pangloss Collection. -

Polyvalent Case, Geometric Hierarchies, and Split Ergativity

[For Jackie Bunting, Sapna Desai, Robert Peachey, Chris Straughn, and Zuzana Tomkova (eds.), (2006) Proceedings of the 42nd annual meeting of the Chicago Linguistics Society, Chicago, Ill.] Polyvalent case, geometric hierarchies, and split ergativity JASON MERCHANT University of Chicago Prominence hierarchy effects such as the animacy hierarchy and definiteness hierarchy have been a puzzle for formal treatments of case since they were first described systematically in Silverstein 1976. Recently, these effects have received more sustained attention from generative linguists, who have sought to capture them in treatments grounded in well-understood mechanisms for case assignment cross-linguistically. These efforts have taken two broad directions. In the first, Aissen 1999, 2003 has integrated the effects elegantly into a competition model of grammar using OT formalisms, where iconicity effects emerge from constraint conjunctions between constraints on fixed universal hierarchies (definiteness, animacy, person, grammatical role) and a constraint banning overt morphological expression of case. The second direction grows out of the work of Jelinek and Diesing, and is found most articulated in Jelinek 1993, Jelinek and Carnie 2003, and Carnie 2005. This work takes as its starting point the observation that word order is sometimes correlated with the hierarchies as well, and works backwards from that to conclusions about phrase structure geometries. In this paper, I propose a particular implementation of this latter direction, and explore its consequences for our understanding of the nature of case assignment. If hierarchy effects are due to positional differences in phrase structures, then, I argue, the attested cross-linguistic differences fall most naturally out if the grammars of these languages countenance polyvalent case—that is, assignment of more than one case value to a single nominal phrase. -

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: a Case Study from Koro

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro By Jessica Cleary-Kemp A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair Assistant Professor Peter S. Jenks Professor William F. Hanks Summer 2015 © Copyright by Jessica Cleary-Kemp All Rights Reserved Abstract Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro by Jessica Cleary-Kemp Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair In this dissertation a methodology for identifying and analyzing serial verb constructions (SVCs) is developed, and its application is exemplified through an analysis of SVCs in Koro, an Oceanic language of Papua New Guinea. SVCs involve two main verbs that form a single predicate and share at least one of their arguments. In addition, they have shared values for tense, aspect, and mood, and they denote a single event. The unique syntactic and semantic properties of SVCs present a number of theoretical challenges, and thus they have invited great interest from syntacticians and typologists alike. But characterizing the nature of SVCs and making generalizations about the typology of serializing languages has proven difficult. There is still debate about both the surface properties of SVCs and their underlying syntactic structure. The current work addresses some of these issues by approaching serialization from two angles: the typological and the language-specific. On the typological front, it refines the definition of ‘SVC’ and develops a principled set of cross-linguistically applicable diagnostics. -

Grammatical Categories and Word Classes Pdf

Grammatical categories and word classes pdf Continue 목차 qualities and phrases about qualities and dalakhin scared qualities are afraid of both hard long only the same, identical adjectives and common adverbs phrases and common adverbs comparison and believe adverbs class sayings of place and movement outside away and away from returning inside outside close up the shifts of time and frequency easily confused the words above or more? Across, over or through? Advice or advice? Affect or affect? Every mother of every? Every mother wholly? Allow, allow or allow? Almost or almost? Single, lonely, alone? Along or side by side? Already, still or yet? Also, as well as or too? Alternative (ly), alternative (ly) though or though? Everything or together? Amount, number or quantity? Any more or any more? Anyone, anyone or anything? Apart from or with the exception? arise or rise? About or round? Stir or provoke? As or like? Because or since then? When or when? Did she go or she?. Start or start? Next to or next? Between or between? Born or endured? Bring, take and bring can, can or may? Classic or classic? Come or go? Looking or looking? Make up, compose or compose? Content or content? Different from or different from or different from? Do you do or make? Down or down or down? During or for? All or all? East or East; North or North? Economic or economic? Efficient or effective? Older, older or older, older? The end or the end? Private or specific? Every one or everybody? Except or with exception? Expect, hope or wait? An experience or an experiment? Fall or fall? Far or far? Farther, farther or farther, farther? Farther (but not farther) fast, fast or fast? Fell or did you feel? Female or female; male or male? Finally, finally, finally or finally? First, first or at first? Fit or suit? Next or next? For mother since then? Forget or leave? Full or full? Funny or funny? Do you go or go? Grateful or thankful? Listen or listen (to)? High or long? Historical or historical? A house or a house? How is he...? Or what is .. -

Workshop Proposal: Associated Motion in African Languages WOCAL 2021, Universiteit Leiden Organizers: Roland Kießling (Universi

Workshop proposal: Associated motion in African languages WOCAL 2021, Universiteit Leiden Organizers: Roland Kießling (University of Hamburg) Bastian Persohn (University of Hamburg) Daniel Ross (University of Illinois, UC Riverside) The grammatical category of associated motion (AM) is constituted by markers related to the verb that encode translational motion (e.g. Koch 1984; Guillaume 2016). (1–3) illustrate AM markers in African languages. (1) Kaonde (Bantu, Zambia; Wright 2007: 32) W-a-ká-leta buta. SUBJ3SG-PST-go_and-bring gun ʻHe went and brought the gun.ʻ (2) Wolof (Atlantic, Senegal and Gambia; Diouf 2003, cited by Voisin, in print) Dafa jàq moo tax mu seet-si la FOC.SUBJ3SG be_worried FOC.SUBJ3SG cause SUBJ3SG visit-come_and OBJ2SG ‘He's worried, that's why he came to see you.‘ (3) Datooga (Nilotic, Tanzania; Kießling, field notes) hàbíyóojìga gwá-jòon-ɛ̀ɛn ʃɛ́ɛróodá bàɲêega hyenas SUBJ3SG-sniff-while_coming smell.ASS meat ‘The hyenas come sniffing (after us) because of the meat’s smell.’ Associated motion markers are a common device in African languages, as evidenced in Belkadi’s (2016) ground-laying work, in Ross’s (in press) global sample as well as by the available surveys of Atlantic (Voisin, in press), Bantu (Guérois et al., in press), and Nilotic (Payne, in press). In descriptive works, AM markers are often referred to by other labels, such as movement grams, distal aspects, directional markers, or itive/ventive markers. Typologically, AM systems may vary with respect to the following parameters (e.g. Guillaume 2016): Complexity: How many dedicated AM markers do actually contrast? Moving argument:: Which is the moving entity (S/A vs. -

Transparency in Language a Typological Study

Transparency in language A typological study Published by LOT phone: +31 30 253 6111 Trans 10 3512 JK Utrecht e-mail: [email protected] The Netherlands http://www.lotschool.nl Cover illustration © 2011: Sanne Leufkens – image from the performance ‘Celebration’ ISBN: 978-94-6093-162-8 NUR 616 Copyright © 2015: Sterre Leufkens. All rights reserved. Transparency in language A typological study ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof. dr. D.C. van den Boom ten overstaan van een door het college voor promoties ingestelde commissie, in het openbaar te verdedigen in de Agnietenkapel op vrijdag 23 januari 2015, te 10.00 uur door Sterre Cécile Leufkens geboren te Delft Promotiecommissie Promotor: Prof. dr. P.C. Hengeveld Copromotor: Dr. N.S.H. Smith Overige leden: Prof. dr. E.O. Aboh Dr. J. Audring Prof. dr. Ö. Dahl Prof. dr. M.E. Keizer Prof. dr. F.P. Weerman Faculteit der Geesteswetenschappen i Acknowledgments When I speak about my PhD project, it appears to cover a time-span of four years, in which I performed a number of actions that resulted in this book. In fact, the limits of the project are not so clear. It started when I first heard about linguistics, and it will end when we all stop thinking about transparency, which hopefully will not be the case any time soon. Moreover, even though I might have spent most time and effort to ‘complete’ this project, it is definitely not just my work. Many people have contributed directly or indirectly, by thinking about transparency, or thinking about me. -

Charles J. Fillmore

Obituary Charles J. Fillmore Dan Jurafsky Stanford University Charles J. Fillmore died at his home in San Francisco on February 13, 2014, of brain cancer. He was 84 years old. Fillmore was one of the world’s pre-eminent scholars of lexical meaning and its relationship with context, grammar, corpora, and computation, and his work had an enormous impact on computational linguistics. His early theoret- ical work in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s on case grammar and then frame semantics significantly influenced computational linguistics, AI, and knowledge representation. More recent work in the last two decades on FrameNet, a computational lexicon and annotated corpus, influenced corpus linguistics and computational lexicography, and led to modern natural language understanding tasks like semantic role labeling. Fillmore was born and raised in St. Paul, Minnesota, and studied linguistics at the University of Minnesota. As an undergraduate he worked on a pre-computational Latin corpus linguistics project, alphabetizing index cards and building concordances. During his service in the Army in the early 1950s he was stationed for three years in Japan. After his service he became the first US soldier to be discharged locally in Japan, and stayed for three years studying Japanese. He supported himself by teaching English, pioneering a way to make ends meet that afterwards became popular with generations of young Americans abroad. In 1957 he moved back to the United States to attend graduate school at the University of Michigan. At Michigan, Fillmore worked on phonetics, phonology, and syntax, first in the American Structuralist tradition of developing what were called “discovery proce- dures” for linguistic analysis, algorithms for inducing phones or parts of speech. -

On Passives of Passives Julie Anne Legate, Faruk Akkuş, Milena Šereikaitė, Don Ringe

On passives of passives Julie Anne Legate, Faruk Akkuş, Milena Šereikaitė, Don Ringe Language, Volume 96, Number 4, December 2020, pp. 771-818 (Article) Published by Linguistic Society of America For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/775365 [ Access provided at 15 Dec 2020 15:14 GMT from University Of Pennsylvania Libraries ] ON PASSIVES OF PASSIVES Julie Anne Legate Faruk Akku s¸ University of Pennsylvania University of Pennsylvania Milena Šereikait e˙ Don Ringe University of Pennsylvania University of Pennsylvania Perlmutter and Postal (1977 and subsequent) argued that passives cannot passivize. Three prima facie counterexamples have come to light, found in Turkish, Lithuanian, and Sanskrit. We reex - amine these three cases and demonstrate that rather than counterexemplifying Perlmutter and Postal’s generalization, these confirm it. The Turkish construction is an impersonal of a passive, the Lithuanian is an evidential of a passive, and the Sanskrit is an unaccusative with an instru - mental case-marked theme. We provide a syntactic analysis of both the Turkish impersonal and the Lithuanian evidential. Finally, we develop an analysis of the passive that captures the general - ization that passives cannot passivize.* Keywords : passive, impersonal, voice, evidential, Turkish, Lithuanian, Sanskrit 1. Introduction . In the 1970s and 1980s, Perlmutter and Postal (Perlmutter & Postal 1977, 1984, Perlmutter 1982, Postal 1986) argued that passive verbs cannot un - dergo passivization. In the intervening decades, three languages have surfaced as prima facie counterexamples—Turkish (Turkic: Turkey), Lithuanian (Baltic: Lithuania), and Classical Sanskrit (Indo-Aryan) (see, inter alia, Ostler 1979, Timberlake 1982, Keenan & Timberlake 1985, Özkaragöz 1986, Baker et al. -

Conventions and Abbreviations

Conventions and abbreviations Example sentences consist of four lines. The first line uses a practical orthography. The second line shows the underlying morphemes. The third line is a gloss, and the fourth line provides a free translation in English. In glosses, proper names are represented by initials. Constituents are in square brackets. Examples are numbered separately for each chapter. If elements are marked in other ways (e.g. with boldface), this is indicated where relevant. A source reference is given for each example; the reference code consists of the initials of the speaker (or ‘Game’ for the Man and Tree games), the date the recording was made, and the number of the utterance. An overview of recordings plus reference codes can be found in Appendix I. The following abbreviations and symbols are used in glosses: 1 first person 2 second person 3 third person ADJ adjectiviser ANIM animate APPL applicative CAUS causative CLF classifier CNTF counterfactual COMP complementiser COND conditional CONT continuative DEF definiteness marker DEM demonstrative DIM diminutive DIST distal du dual EMP emphatic marker EXCL exclusive FREE free pronoun FOC focus marker HAB habitual IMP imperative INANIM inanimate INCL inclusive INT intermediate INTJ interjection INTF intensifier IPFV imperfective IRR irrealis MOD modal operator NEG negation marker NOM nominaliser NS non-singular PART partitive https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110675177-206 XXIV Conventions and abbreviations pc paucal PERT pertensive PFV perfective pl plural POSS possessive PRF perfect PROG progressive PROX proximate RECIP reciprocal REDUP reduplication REL relative clause marker sg singular SPEC.COLL specific collective SUB subordinate clause marker TAG tag question marker ZERO person/number reference with no overt realisation - affix boundary = clitic boundary . -

Assigning Roles to Constituents of Sentences

, " CHAPTER 19 Mechanisms of Sentence Processing: Assigning Roles to Constituents of Sentences J. L. McCLELLAND and A. H. KAWAMOTO MUL TIPLE CONSTRAINTS ON ROLE ASSIGNMENT Like many natural cognitive processes , the process of sentence comprehension involves the simultaneous consIderation of a large number of different sources of information. In this chapter, we con- sider one aspect of sentence comprehension: the assignment of the constituents of a sentence to the correct thematic case roles. Case role assignment is not , of ' course , all there is to comprehension, but it reflects one important aspect of the comprehension process, namely, the specification of who did what to whom. Case role assignment is not at all a trivial matter either, as we can see by considering some sentences and the case roles we assign to their constituents. We begin with several sentences using the verb break: (I) The boy broke the window. (2) The rock broke the window. (3) The window broke. (4) The boy broke the window with the rock. (5) The boy broke the window with the curtain. We can see that the assignment of case roles here is quite complex. The first noun phrase (NP) of the sentence can be the Agent (Sen- tences 1 , 4, and 5), the Instrument (Sentence 2), or the Patient 19. SENTENCE PROCESSING 273 (Sentence 3). The NP in the prepositional phrase (PP) could' be the Instrument (Sentence 4), or it could be a Modifier of the second NP as it is in at least one reading of Sentence 5. Another example again brings out the ambiguity of the role assignment of with-NPs: (6) The boy ate the pasta with the sauce. -

Author Index

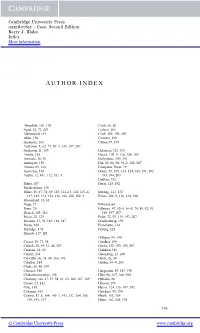

Cambridge University Press 0521807611 - Case, Second Edition Barry J. Blake Index More information AUTHOR INDEX Abondolo, 101, 105 Cook, 66, 80 Agud, 32, 72, 207 Corbett, 104 Aikhenvald, 191 Croft, 192, 193, 207 Allen, 150 Crowley, 100 Andersen, 163 Cutler, 99, 190 Anderson, J., 62, 71, 80–3, 135, 197, 207 Anderson, S., 109 Delancey, 123, 192 Anttila, 165 Dench, 108–9, 116, 154, 190 Aristotle, 18, 30 Derbyshire, 100, 191 Armagost, 156 Dik, 62, 66, 68, 91–2, 188, 207 Artawa, 89, 124 Dionysius Thrax, 19 Austerlitz, 165 Dixon, 56, 105, 114, 124, 185, 191, 192, Austin, 12, 101, 112, 182–3 193, 194, 207 DuBois, 192 Baker, 187 Durie, 124, 192 Balakrishnan, 158 Blake, 15, 67, 78, 89, 107, 114–15, 124, 127–8, Ebeling, 121, 152 137, 143, 151, 154, 158, 186, 188, 192–3 Evans, 108–9, 116, 154, 190 Bloomfield, 13, 63 Bopp, 37 Filliozat, 64 Bowe, 26 Fillmore, 47, 62–3, 66–8, 74, 80, 82, 91, Branch, 105, 116 188, 197, 207 Breen, 28, 125 Foley, 72, 92, 110, 192, 207 Bresnan, 47, 92, 185, 186, 187 Frachtenberg, 190 Bryan, 102 Franchetto, 124 Burridge, 174 Friberg, 123 Burrow, 117, 181 Gilligan, 99, 190 Caesar, 19, 73, 98 Giridhar, 100 Calboli, 18, 19, 31, 48, 207 Giv´on, 112, 192, 193, 207 Cardona, 64, 65 Goddard, 186 Carroll, 138 Greenberg, 15, 160 Carvalho, de, 31, 40, 186, 192 Groot, de, 30 Catullus, 184 Gruber, 67–9, 205 Chafe, 66, 80, 207 Chaucer, 148 Haegeman, 59, 187, 190 Chidambaranathan, 158 Hale, 96, 107, 168, 194 Chomsky, xiii, 47, 57, 58, 61, 62, 186, 187, 189 Halliday, 66 Cicero, 23, 112 Hansen, 193 Cole, 110 Harris, 124, 126, 147, 192 Coleman, 105 Hawkins, 99, 190 Comrie, 87–8, 104, 140–1, 142, 152, 154, 185, Heath, 155, 159 190, 191, 207 Heine, 162, 165, 193 219 © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521807611 - Case, Second Edition Barry J. -

Spatial Semantics, Case and Relator Nouns in Evenki

Spatial semantics, case and relator nouns in Evenki Lenore A. Grenoble University of Chicago Evenki, a Northwest Tungusic language, exhibits an extensive system of nominal cases, deictic terms, and relator nouns, used to signal complex spatial relations. The paper describes the use and distribution of the spatial cases which signal stative and dynamic relations, with special attention to their semantics within a framework using fundamental Gestalt concepts such as Figure and Ground, and how they are used in combination with deictics and nouns to signal specific spatial semantics. Possible paths of grammaticalization including case stacking, or Suffixaufnahme, are dis- cussed. Keywords: spatial cases, case morphology, relator noun, deixis, Suf- fixaufnahme, grammaticalization 1. Introduction Case morphology and relator nouns are extensively used in the marking of spa- tial relations in Evenki, a Tungusic language spoken in Siberia by an estimated 4802 people (All-Russian Census 2010). A close analysis of the use of spatial cases in Evenki provides strong evidence for the development of complex case morphemes from adpositions. Descriptions of Evenki generally claim the exist- ence of 11–15 cases, depending on the dialect. The standard language is based on the Poligus dialect of the Podkamennaya Tunguska subgroup, from the Southern dialect group, now moribund. Because it forms the basis of the stand- ard (or literary) language and as such has been relatively well-studied and is somewhat codified, it usually serves as the point of departure in linguistic de- scriptions of Evenki. However, the written language is to a large degree an artifi- cial construct which has never achieved usage in everyday conversation: it does not function as a norm which cuts across dialects.