Vol. 8, No. 3: Full Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

19-04-HR Haldeman Political File

Richard Nixon Presidential Library Contested Materials Collection Folder List Box Number Folder Number Document Date No Date Subject Document Type Document Description 19 4 Campaign Other Document From: Harry S. Dent RE: Profiles on each state regarding the primary results for elections. 71 pgs. Monday, March 21, 2011 Page 1 of 1 - Democratic Primary - May 5 111E Y~'ilIIE HUUSE GOP Convention - July 17 Primary Results -- --~ -~ ------- NAME party anncd fiJ cd bi.lc!<ground GOVERNORIS RACE George Wallace D 2/26 x beat inc Albert Brewer in runoff former Gov.; 68 PRES cando A. C. Shelton IND 6/6 former St. Sen. Dr. Peter Ca:;;hin NDPA endorsed by the Negro Democratic party in Aiabama NO SENATE RACE CONGRESSIONAL 1st - Jack Edwards INC R x x B. H. Mathis D x x 2nd - B ill Dickenson INC R x x A Ibert Winfield D x x 3rd -G eorge Andrews INC D x x 4th - Bi11 Nichols INC D x x . G len Andrews R 5th -W alter Flowers INC D x x 6th - John Buchanan INC R x x Jack Schmarkey D x x defeated T ito Howard in primary 7th - To m Bevill INC D x x defeated M rs. Frank Stewart in prim 8th - Bob Jones INC D x x ALASKA Filing Date - June 1 Primary - August 25 Primary Re sults NAME party anned filed bacl,ground GOVERNOR1S RACE Keith Miller INC R 4/22 appt to fill Hickel term William Egan D former . Governor SENATE RACE Theodore Stevens INC R 3/21 appt to fill Bartlett term St. -

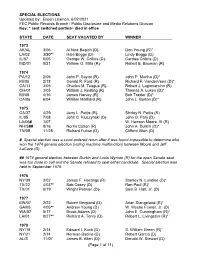

Special Election Dates

SPECIAL ELECTIONS Updated by: Eileen Leamon, 6/02/2021 FEC Public Records Branch / Public Disclosure and Media Relations Division Key: * seat switched parties/- died in office STATE DATE SEAT VACATED BY WINNER 1973 AK/AL 3/06 Al Nick Begich (D)- Don Young (R)* LA/02 3/20** Hale Boggs (D)- Lindy Boggs (D) IL/07 6/05 George W. Collins (D)- Cardiss Collins (D) MD/01 8/21 William O. Mills (R)- Robert E. Bauman (R) 1974 PA/12 2/05 John P. Saylor (R)- John P. Murtha (D)* MI/05 2/18 Gerald R. Ford (R) Richard F. VanderVeen (D)* CA/13 3/05 Charles M. Teague (R)- Robert J. Lagomarsino (R) OH/01 3/05 William J. Keating (R) Thomas A. Luken (D)* MI/08 4/16 James Harvey (R) Bob Traxler (D)* CA/06 6/04 William Mailliard (R) John L. Burton (D)* 1975 CA/37 4/29 Jerry L. Pettis (R)- Shirley N. Pettis (R) IL/05 7/08 John C. Kluczynski (D)- John G. Fary (D) LA/06# 1/07 W. Henson Moore, III (R) NH/S## 9/16 Norris Cotton (R) John A. Durkin (D)* TN/05 11/25 Richard Fulton (D) Clifford Allen (D) # Special election was a court-ordered rerun after it was found impossible to determine who won the 1974 general election (voting machine malfunction) between Moore and Jeff LaCaze (D). ## 1974 general election between Durkin and Louis Wyman (R) for the open Senate seat was too close to call and the Senate refused to seat either candidate. Special election was held in September 1975. -

Mn 2000 MAPS 01133.Pdf (526.3Kb Application/Pdf)

: • • ," ·, .•• > ••• ~· ; ~ : l I / ,.' ._. DIRECTORY MINNESOTA STATE & FEDERAL LEGISLATORS 1975 (J\ jl,\ ! Ii l: ("C.., Cifd t x'.k/n~.; o ;, ::.~ l :, '• ..'.C published as a public service by (g) ~JN NlS OIA AN-4\_LYSIS & PLANNING SYSJ_EM. AG RIC UL TURAL EXTENSION SERVICE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA ,,~7 ST. PAUL, MN 55108 --?- ;1115(1,,,,. > Ir' 1 "-,.--,:, ::__ I c1 "' .,- DIREC~ORY MINNESOTA STATE and FEDERAL LEGISLATORS This Directory was prepared by the staff of the Minnesota Analysis and Plan ning System (MAPS), which is part of the Agricultural Extension Service, University of Minnesota. Informational input for the Directory was acquired from legislative off ices and individual members of the legislature. Costs of preparation and publication have been borne by MAPS and any changes, additions, or corrections should be sent to MAPS at the address listed below. Single copies of the Directory will be sent free of charge to individuals re questing them as long as the supply lasts. MAPS cannot honor requests for free mul tiple copies to organizations, but will consider such orders on a cost-reimburse ment basis. Further information can be obtained by contacting: Minnesota Analysis and Planning System (MAPS) 415 Coffey Hall University of Minnesota St. Paul, MN 55108 Ph. (612) 376-7003 i. District ~ ~ ~ FITZSIMONS 19 ANDERSON lA BRAUN 19A CLAWSON lB CORBID 19B MANGAN 2 MOE 20 JOSEFSON 2A KELLY 20A SMOGARD 2B EKEN 20B STANTON J ARNOLD 21 OLSON JA ANDERSON 21A LINDSTROM JB PRAHL 21B SETZEPPANDT 4 WILLET 22 BERNHAGEN 4A ONGE 22A KVAM 4B SHERWOOD 22B DAHL s PERPICH 2J RENNEKE SA FU GINA 2JA ALBRECHT SB SPANISH 2JB JOHNSON 6 PERPICH 24 PURFEERST 6A BEGICH 24A VANASEK 6B JOHNSON 24B BIRNSTIHL 7 SOLON 2S CONZEMIUS 7A MUNGER 25A WHITE 7B JAROS 2SB SCHULZ B DOTY 26 OLSON BA DOTY 26A MENNING BB ULLAND 26B ERICKSON 9 SILLERS 27 OLSON 9A BEAUCHAMP 27A MANN 98 LANGSETH 278 PETERSON 10 HANSON 2B JENSEN lOA DEGROAT 2BA ESAU 108 GRABA 288 ECKSTEIN 11 OLHOFr 29 UELAND, JR. -

Tobacco Industry in Transition the Tobacco Industry in Transition

•i_r, _ : #w .1o nt. Md' rYrM$ ! i 1ip1 ' _f awret ysrswldsw ° . :' ! • '; : a 1 : I The Tobacco Industry in Transition The Tobacco Industry in Transition Policies for the 1980s Edited by William R. Finger North Carolina Center for Public Policy Research, Inc. LexingtonBooks D.C. Heath and Company Lexington, Massachusetts Toronto Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Main entry under title: The Tobacco industry in transition. 1. Tobacco manufacture and trade-Government policy-United States. 2. Tobacco manufacture and trade-United States. I. Finger, William R. II. North Carolina Center for Public Policy Research. HD9136.T6 338.1'7371'0973 81-47064 ISBN 0-669-04552-7 AACR2 Copyright © 1981 by North Carolina Center for Public Policy Research, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmit- ted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Published simultaneously in Canada Printed in the United States of America International Standard Book Number: 0-669-04552-7 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 81-47064 Contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction William R. Finger Xi Part I The Tobacco Program and the Farmer 1 Chapter 1 Early Efforts to Control the Market-And Why They Failed Anthony J. Badger 3 Chapter 2 The Federal Tobacco Program: How It Works and Alternatives for Change Charles Pugh 13 Chapter 3 Landmarks in the Tobacco Program Charles Pugh 31 Chapter -

Inventory List 3

Brothers of the Century Awarded at the 2004 Alpha Gamma Rho Page 1 of 59 National Convention Charles A. Stewart BOC ID#: 10013 University of Illinois 1906 Charles A. Stewart was initiated into Delta Rho Sigma in 1906. He represented the fraternity at the “marriage” between Delta Rho Sigma and Alpha Gamma Rho. Afterward he served as the first Grand President of Alpha Gamma Rho at the first National Convention held on November 30, 1908 at the Hofbrau Hotel in Chicago. Albert B. Sawyer, Jr. BOC ID#: 10039 University of Illinois 1908 Albert B. Sawyer was initiated into Delta Rho Sigma in 1906. He was the moderator at the “marriage” of Alpha Gamma Rho and Delta Rho Sigma. He kept the minutes of the first meetings. According to Brother Sawyer, the minutes were on two paper place mats bearing the name of Hofbrau (Chicago). At the first national convention held November 30, 1908, Brother Sawyer served as the Grand Secretary and Treasurer. Nathan L. Rice BOC ID#: 10186 University of Illinois 1916 Nathan L. Rice is a long time supporter of Alpha Gamma Rho. He grew up on the family farm in Philo, Illinois. In 1915 Nathan became a member of Alpha Gamma Rho at the University of Illinois. In April of 1918 he was enlisted in World War I. He returned to the University of Illinois in September of 1919. After graduation, Brother Rice returned to the farm and in 1924 accepted the position as President of the Philo Exchange Bank. In 1923 Sleeter Bull asked Brother Rice to write the history of Alpha Gamma Rho. -

Cobbers Invade Munchkinland Wizard Promises to Delight Parents

^^ ••;\ » VOLUME 62 CONCORDIA COLLEGE, MOORHEAD, MINNESOTA, MARCH 36. 1071 No. 15 Vs *?KW ***' lOrfU. ••*> In a tense moment. Dor thy (Kathleen Butz) and Toto (Neoma Meiers) are comforted by their three companians, the Woodsman (Orion Hunter), the Cowardly Lion (Randall Johnson, and the Scare Cobbers crow (Dean Brown). invade Munchkinland JUDY LIEN professional, per se, yet cooper- Penny Matthews. Lord Growley, donated by the McDowall Roof- Oz people pport outfits rented Staff Writer ation and hard work by the Jack Leininger, his daughter ing Company in St. Cloud. The from theatrical companies. huge company has made "Oz" Gloria, Katey Tabaka, and the Cowardly Lion, Munchkins, and Terry Goldman invented et- Follow the yellow brick road! a fun and fanciful endeavor. loyal citizens of Oz royally en- hereal pets that capture all the Follow the yellow brick road Enthusiasm and humor have tertain Dorothy, Tinman, Lion, mystery and magic of this mus- over to the Concordia fieldhouse saved many a rehearsal. and Scarecrow while the ne- ical fairy tale. to see one of the four delightful bulous Wizard roars, smokes Performances began last Kathleen Butz plays Dorothy performances of "The Wizard of and thoroughly terrifies this night and will run tonight and Gale, the young singing char- humble quartet, keeping them Saturday at 8:00 p.m., with a mer transplanted from Kansas waiting with their requests. Children's Matinee Saturday af- to the land of Oz by a summer The Great Oz "humbug" Gerald ternoon at 2:00 p.m. Reserve twister. With the help of the Goth does aptly award their tickets for evening performances Mayor of Munchkin City, pleas with true wizardly in- are available at $2.00, $2.50, and Harold Anderson, and all his sight. -

Interview with Robert Bergland Interviewed by Associate Dean Ann

Interview with Robert Bergland Interviewed by Associate Dean Ann M. Pflaum University of Minnesota Interviewed on April 9, 1999 Robert Bergland - RB Ann Pflaum - AP AP: This is Ann Pflaum. Today is April 9, 1999. I am interviewing the Honorable Robert Bergland, who is, at the moment, a member of the Board of Regents; but, I'm going to ask him for an update of his biography, including his early education, his high school, college, and his career in Washington, if you will. Thank you very much. RB: I was born on July 22, 1928, at Roseau way up in the northern end of the state. My mother was a school teacher. She had graduated from the one-room country school and gone to Bemidji State Normal for two years of training and was licensed to teach school in those rural places. I think she started teaching when she was seventeen years of age. My dad was a Ford Motor Company mechanic and mom and dad had a farm just south of Roseau, which I now own. I graduated from the Roseau public school system in the fall of 1946 during the war time. World War II time had a major impact on my life. My dad had been a soldier in World War I, so he had more than a casual interest in this whole thing as well. I was very interested in farming. We lived on a farm and I could sense that there were important changes developing in farming; that is, new technology was on the horizon, not yet quite available, but it was on its way. -

Exte,Nsions of Remarks

8606 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS March fl~ , 1977 EXTE,NSIONS OF REMARKS NATIONAL AGRICULTURE DAY, Of particular interest to farmers this a "caseload" of as many as four young MARCH 21, 1977 year will be provisions in the farm bill sters simultaneously. Indeed, I am grate concerning price supports, grain reserves, ful for the St. Paul Dispatch article and disaster payments, agricultural research, the attention paid to this side of the HON. MARC L. MARKS and food aid. Very often consumer and many-sided Dick Long and his numer OF PENNSYLVANIA farmer views on these issues differ; the ous good works. His versatility is IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES contention revolves around prices paid acknowledged by the fact that he offici Monday, March 21, 1977 and received for agricultural goods. I ated at both the winter carnival-and Mr. MARKS. Mr. Speaker, I rise in would encourage each of us this year to we ~re well known for our winters in St. tribute today, National Agriculture Day, carefully consider the best way to first, Paul-and the St. Patrick's Day parade to our Nation's 1 % million farmers and assure farmers a fair and adequate re during our salubrious springtime. The farmworkers. Special attention needs to turn in years of less than 100 percent of realization that it snowed on March 17, be paid these fine people this year for the production world market demand-those although the chamber of commerce amazing job they perform. Although this years when overproduction depresses called it sleet, did nothing to quell the group comprises only about 1 % percent prices. -

Extensions of Remarks

March 9, 1978 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 6333 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS CARMAN SCHOOL FOLLOW low-income fam111es-to know success in certain that-as the night the day-the THROUGH PROGRAM CITED BY school," says Mrs. Merle Holzman, Follow mass mailings are sure to follow. Through coordinator. So every ttme a child U.S. OFFICE OF EDUCATION does well, the teacher, aide or parent assist Most of these mailings concern them ant praises htm. "That's good, Johnnny. You selves with issues which bear directly HON. ROBERT McCLORY sounded out the word just right." And with on the senders' desires. Rights they want the compliment may come a token which protected. Regulations they want OF ILLINOIS the child wlll use later to "buy" a special blocked. Federal interference they want IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES privilege. stopped. Bills they want passed. And, all Thursday, March 9, 1978 Children in kindergarten wear plastic too frequently, handouts they want aprons in which to pocket their tokens. First given or prerogatives they want guaran e Mr. McCLORY. Mr. Speaker, I have and second graders each have their own long been a proud and staunch supporter token cup. teed. of the Follow Through program at the Tokens are "earned" during the morning For this reason, I was particularly im Carman Elementary School in Wauke classes which focus on basic skUls. Shortly pressed and moved by the recent flood gan in my 13th Congressional District. before noon, the youngsters get to spend of mail I have receiv~d from citizens them. At that time, the teacher lists on the across this country who support the Just yesterday, a fine feature article on board six activities which they may buy. -

Winona Daily & Sunday News

Winona State University OpenRiver Winona Daily News Winona City Newspapers 5-1-1972 Winona Daily News Winona Daily News Follow this and additional works at: https://openriver.winona.edu/winonadailynews Recommended Citation Winona Daily News, "Winona Daily News" (1972). Winona Daily News. 1158. https://openriver.winona.edu/winonadailynews/1158 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Winona City Newspapers at OpenRiver. It has been accepted for inclusion in Winona Daily News by an authorized administrator of OpenRiver. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ;¦ ' :¦ ' ¦ ¦/ Rain through " GOT IOTS OF ^^y^. Tuesday; chance JINGUN' MONEY fe^sgv Sold Hy CorThra AWontAd of thunderstorms J l^tf&r 117th Year of Publication 2 Sections, 18 ' ' Page 's-, 15 Cents S. Viets Nixon on Vietnam— abandon Ground forces are out By FRANK CORMIER Later Nixon sai dthe Saigon forces could resist success- FLORESVILLE Tex7 (AP)— President Nixon fully, provided the United States continues to supply air and , says no ' ' Quang Tri U.S. ground forces will be recommitted to the stepped-up naval, support. ; . war in South Vietnam but declares Hanoi runs " The President and Mrs. Nixon were overnight guests at ) a very great SAIGON <AP - South Viet- risk'' with its current offensive. the Picosa ranch of Connally, the only Democrat in the Cabi- nam's first provincial capital Nixon net and a man still mentioned as a possible replacement fell to the North Vietnamese to- , inviting questions from a blue-ribbon crowd of Texans at tbe ranch of Treasury Secretary John B. Con- for Vice President Spiro T. -

RIPON a Special Pre-Election Report

RIPON NOVEMBER, 1970 VOl. VI No. 11 ONE DOLLAR • The Raging Political Battles • The Apathetic Voter • The Stakes for Nixon in '72 A Special Pre-Election Report SUMMARY OF CONTENTS THE RIPON SOCIETY, INC. ~I~ o~:~:r!~:n :.-~ ~ bers are young business, acadamlc and professIonal men and wonnm. It has national headquarters in CambrIdge, Massachusatta, chapters In elmm EDITORIAL 3 cities, National AssocIate members throughout the fIfty states, and several affiliated groups of subchapter status. The SocIety is supported iIy cbspler dues, individual contributions and revenues from Its pUblications and con· tract work. The SocIety offers the followIng options for annual amtrIbu· RIPON: 'ENDORSEMENTS 5 tion: Contributor $25 or more: Sustalner $100 or more: Founder $1000 or more. Inquiries about membershIp and chapter organization abaIIId be addressad to the National Executlva Dlrectar. POLITICAL NOTES 6 NATIONAl GOVERNING BOARD OffIcers PRE-ELECTION REPORTS • Josiah Lea Auspitz, PresIdent 'Howard F. Gillett., Jr., Chairman of the Board 'Bruce K. Chapman, ChaIrman of the £Ie:utln CommIttee New York -10 'Mlchaei F. Brewer, VIca·Presldent • Robert L. Beal, Treasurer Pennsylvania -15 'Richard E. Beaman, Secretal1 Sastan Phlladalpbla "Robert Gulick 'Richard R. Block Martin A. Linsky Charles Day Ohio -18 Michael W. Christian Roger Whittlesey Combrldge Seattle 'Robert Davidson 'Thomas A. Alberg Texas -20 David A. Reil Camden Hail Rhea Kemble Wi lIIam Rodgers ChIcago WashIngton Massachusetts -23 ·R. Quincy White, Jr. 'Patricia A. Goldman 'Haroid S. Russell Stepben Herbits George H. Walker III Linda K. Lee Michigan -25 Dalles 'Neil D. Anderson At Large Howard L. Abramson "Chrlstopher T. Bayley Robert A. Wilson Thomas A. -

DESCHLER-BROWN- JOHNSON-SULLIVAN PRECEDENTS of the United States House of Representatives

94th Congress, 2d Session - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - House Document No. 94–661 DESCHLER-BROWN- JOHNSON-SULLIVAN PRECEDENTS OF THE United States House of Representatives By LEWIS DESCHLER, J.D., D.J., M.P.L., LL.D. Parliamentarian of the House, 1928–1974 WM. HOLMES BROWN, J.D. Parliamentarian of the House, 1974–1994 CHARLES W. JOHNSON, III, J.D. Parliamentarian of the House, 1994–2004 JOHN V. SULLIVAN, J.D. Parliamentarian of the House, 2004–2012 VOLUME 18 COVERING PRECEDENTS THROUGH THE 112TH CONGRESS AND EMPLOYING CITATIONS TO THE RULES AND TO THE HOUSE RULES AND MANUAL OF THAT PERIOD WHICH HAVE SUBSEQUENTLY BEEN RECODIFIED AS SHOWN IN H. DOC. 106–320 AT PAGES XIII–XV For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Aug 31 2005 09:08 Feb 11, 2013 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 8879 Sfmt 8879 F:\PRECEDIT\VOL18\CH41-2~1\VOL18C~1 27-6A VerDate Aug 31 2005 09:08 Feb 11, 2013 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 8879 Sfmt 8879 F:\PRECEDIT\VOL18\CH41-2~1\VOL18C~1 27-6A Foreword to Bound Volume 18 The publication of volume 18 of Deschler-Brown-Johnson-Sul- livan Precedents marks the completion of the compilation of modern precedents of the House of Representatives commenced by then Parliamentarian Lewis Deschler in 1974. The volume contains the forty-first and final chapter in the series as well as an appendix authored by former Parliamentarian Charles W.