Minnesota Environmental Issues Oral History Project Minnesota Historical

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book Review of Roberta Walburn, "Miles Lord: the Maverick Judge

Joyful Judicial Pugilist MMMILES LLLORD ::: TTTHE MMMAVERICK JJJUDGE WWWHO BBBROUGROUGHTHT CCCORPORATE AAAMERICA TO JJJUSTICE *** by Roberta Walburn Reviewed by Michael A. Wolff Senator Eugene McCarthy stopped by to see Judge Miles Lord one day in the Fall of 1970, when I was the judge’s law clerk. While tthehe judge finished up some business in his office, McCarthy “confided” to me that his support of Lord’s appointment to the bench was one part of his twotwotwo-two ---partpart plan to solve the problem of judicial workloadsworkloads.. “I figured with Miles on the bench, no one would be crazy enough to try their cases,” the senator said. And if they did, the second part of the senator’s plan was to put Jerry Heaney on the Court of Appeals because “no one would be dumb enough to appeaappeal.”l.”l.”l.” The senator’s plan ––– spoken with tongue planted firmly in cheek ––– did not work. Miles Lord proved to be a wily and dedicated fighter for justice, managing and trying a fascinating array of groundground---- breaking cases. And the Court of Appeals with Judge HeaHeaneyney got plenty of interesting business from Lord’s courtcourt---- room. Lord and his reviewers in the Court of Appeals were wary of one another, to put it mildly. The appeals judjudgesges were not his biggest fans. I could give you citations,citations, gentle reader, but this is not a scholarly review and you can Google for yourself. But a story Judge Lord gleefully told me may suffice: Shortly after he lefleftttt the bench in September 1985, Joan Kroc, recently widowed wife of __________________ * University of Minnesota Press, 384 pages (2017) 1 McDonald’s founder Ray Kroc, was in the Twin Cities and wanted to consult with Lord. -

Results of Elections Attorneys General 1857

RESULTS OF ELECTIONS OF ATTORNEYS GENERAL 1857 - 2014 ------- ※------- COMPILED BY Douglas A. Hedin Editor, MLHP ------- ※------- (2016) 1 FOREWORD The Office of Attorney General of Minnesota is established by the constitution; its duties are set by the legislature; and its occupant is chosen by the voters. 1 The first question any historian of the office confronts is this: why is the attorney general elected and not appointed by the governor? Those searching for answers to this question will look in vain in the debates of the 1857 constitutional convention. That record is barren because there was a popular assumption that officers of the executive and legislative branches of the new state government would be elected. This expectation was so deeply and widely held that it was not even debated by the delegates. An oblique reference to this sentiment was uttered by Lafayette Emmett, a member of the Democratic wing of the convention, during a debate on whether the judges should be elected: I think that the great principle of an elective Judiciary will meet the hearty concurrence of the people of this State, and it will be entirely unsafe to go before any people in this enlightened age with a Constitution which denies them the right to elect all the officers by whom they are to be governed. 2 Contemporary editorialists were more direct and strident. When the convention convened in St. Paul in July 1857, the Minnesota Republican endorsed an elected judiciary and opposed placing appointment power in the chief executive: The less we have of executive patronage the better. -

19-04-HR Haldeman Political File

Richard Nixon Presidential Library Contested Materials Collection Folder List Box Number Folder Number Document Date No Date Subject Document Type Document Description 19 4 Campaign Other Document From: Harry S. Dent RE: Profiles on each state regarding the primary results for elections. 71 pgs. Monday, March 21, 2011 Page 1 of 1 - Democratic Primary - May 5 111E Y~'ilIIE HUUSE GOP Convention - July 17 Primary Results -- --~ -~ ------- NAME party anncd fiJ cd bi.lc!<ground GOVERNORIS RACE George Wallace D 2/26 x beat inc Albert Brewer in runoff former Gov.; 68 PRES cando A. C. Shelton IND 6/6 former St. Sen. Dr. Peter Ca:;;hin NDPA endorsed by the Negro Democratic party in Aiabama NO SENATE RACE CONGRESSIONAL 1st - Jack Edwards INC R x x B. H. Mathis D x x 2nd - B ill Dickenson INC R x x A Ibert Winfield D x x 3rd -G eorge Andrews INC D x x 4th - Bi11 Nichols INC D x x . G len Andrews R 5th -W alter Flowers INC D x x 6th - John Buchanan INC R x x Jack Schmarkey D x x defeated T ito Howard in primary 7th - To m Bevill INC D x x defeated M rs. Frank Stewart in prim 8th - Bob Jones INC D x x ALASKA Filing Date - June 1 Primary - August 25 Primary Re sults NAME party anned filed bacl,ground GOVERNOR1S RACE Keith Miller INC R 4/22 appt to fill Hickel term William Egan D former . Governor SENATE RACE Theodore Stevens INC R 3/21 appt to fill Bartlett term St. -

Results of Elections Attorneys General 1857

RESULTS OF ELECTIONS OF ATTORNEYS GENERAL 1857 - 2010 ------- ※------- COMPILED BY Douglas A. Hedin Editor, MLHP ------- ※------- (2013) 1 FOREWORD The Office of Attorney General of Minnesota is established by the constitution; its duties are set by the legislature; and its occupant is chosen by the voters. 1 The first question any historian of the office confronts is this: why is the attorney general elected and not appointed by the governor? Those searching for answers to this question will look in vain in the debates of the 1857 constitutional convention. That record is barren because there was a popular assumption that officers of the executive and legislative branches of the new state govern- ment would be elected. This expectation was so deeply and widely held that it was not even debated by the delegates. An oblique reference to this sentiment was uttered by Lafayette Emmett, a member of the Democratic wing of the convention, during a debate on whether the judges should be elected: I think that the great principle of an elective Judiciary will meet the hearty concurrence of the people of this State, and it will be entirely unsafe to go before any people in this enlightened age with a Constitution which denies them the right to elect all the officers by whom they are to be governed. 2 Contemporary editorialists were more direct and strident. When the convention convened in St. Paul in July 1857, the Minnesota Republican endorsed an elected judiciary and opposed placing appointment power in the chief executive: The less we have of executive patronage the better. -

Ruth Adler Schnee 2015 Kresge Eminent Artist the Kresge Eminent Artist Award

Ruth Adler Schnee 2015 Kresge Eminent Artist The Kresge Eminent Artist Award honors an exceptional artist in the visual, performing or literary arts for lifelong professional achievements and contributions to metropolitan Detroit’s cultural community. Ruth Adler Schnee is the 2015 Left: Keys, 1949. (© Victoria and Albert Museum, London); right: drawing, Glyphs, 1947. Kresge Eminent Artist. This (Courtesy Cranbrook Archives, The Edward and Ruth Adler Schnee Papers.) monograph commemorates her Shown on cover background: Fancy Free, 1949. (Photograph by R.H. Hensleigh and Tim Thayer, life and work. courtesy Cranbrook Art Museum); top left: Woodleaves, 1998; top right: Narrow Gauge, 1957; top center: Bells, 1995; bottom center: Funhouse, 2000; bottom: Plaid, 2001 reissue. Contents 5 57 Foreword Other Voices: By Rip Rapson Tributes and Reflections President and CEO Nancy E. Villa Bryk The Kresge Foundation Lois Pincus Cohn 6 David DiChiera Artist’s Statement Maxine Frankel Bill Harris Life Gerhardt Knoedel 10 Naomi Long Madgett Destiny Detroit Bill Rauhauser By Ruth Adler Schnee 61 13 Biography Transcendent Vision By Sue Levytsky Kresge Arts In Detroit 21 68 Return to Influence Our Congratulations By Gregory Wittkopp From Michelle Perron 22 Director, Kresge Arts in Detroit Generative Design 69 By Ronit Eisenbach A Note From Richard L. Rogers President Design College for Creative Studies 25 70 Inspiration: Modernism 2014-15 Kresge Arts in By Ruth Adler Schnee Detroit Advisory Council 33 Designs That Sing The Kresge Eminent Artist By R.F. Levine Award and Winners 37 72 The Fabric of Her Life: About The Kresge A Timeline Foundation 45 Shaping Contemporary Board of Trustees Living: Career Highlights Credits Community Acknowledgements 51 Between Two Worlds By Glen Mannisto 54 Once Upon a Time at Adler-Schnee, the Store By Gloria Casella Right: Drawing, Raindrops, 1947. -

Book Reviews

Book rEviEWs Miles Lord: The Maverick Judge Who Brought Corporate America to Justice Roberta Walburn (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017, 400 p., Cloth, $29.95.) In Miles Lord: The Maverick Judge Who Brought Corporate Amer- ica to Justice, Roberta Walburn tells the story of the man Hubert Humphrey once described as “the people’s judge” and who was perhaps the most consequential (and controversial) judge ever to serve on the US District Court for Minnesota. The book is structured through alternating chapters that juxtapose Lord’s life (1919–2016) with his involvement in what was, at the time in the 1980s, one of the largest tort liability cases in the country— the litigation for the Dalkon Shield intrauterine contraceptive device (IUD). Walburn’s approach reveals the threads that ran through Lord’s life and guided his judicial decision- making. Miles Lord was born on Minnesota’s Iron Range, coming of age during the Great Depression. After serving in the air force during World War II, he attended the University of Minnesota Law School, graduating in 1948. Though not a member of the Democratic- Farmer- Labor Party’s founding generation, as a young attorney Lord entered Hubert Humphrey’s orbit and bankruptcy of A. H. Robins and a judicial review of Lord’s pro- was twice elected Minnesota attorney general. Later, Lord fessional and judicial conduct. (He was exonerated.) served as US district attorney. The activism Lord engaged in openly, many do privately. In 1966 President Lyndon Johnson appointed Lord to In Lord’s eyes, the law was not neutral, and he often observed, the federal bench, where he served for nearly two decades. -

Detroit's Grand Bargain

Detroit’s Grand Bargain Philanthropy as a Catalyst for a Brighter Future Irene Hirano Inouye Philanthropic Leadership Fund The Center on Philanthropy & Public Policy University of Southern California About the Center on Phil AnthroPy & PubliC PoliCy The Center on Philanthropy and Public Policy promotes more effective philanthropy and strengthens the nonprofit sector through research that informs philanthropic decision-making and public policy to advance public problem solving. Using California and the West as a laboratory, The Center conducts research on philanthropy, volunteerism, and the role of the nonprofit sector in America’s communities. In order to make the research a catalyst for understanding and action, The Center encourages communication among the philanthropic, nonprofit, and policy communities. This is accomplished through a series of convenings and conversations around research findings and policy issues to help key decision makers work together more effectively to solve public problems and to identify strategies for action. This case study is underwritten by the Irene Hirano The Center on Philanthropy & Public Policy Inouye Philanthropic Leadership Fund at The Center Sol Price School of Public Policy on Philanthropy & Public Policy. University of Southern California We want to acknowledge the assistance of Michael Lewis Hall, Room 210 Thom, and the insights and perspectives offered Los Angeles, California 90089-0626 by the individuals interviewed for this case. Listed Phone: (213) 740-9492 at the end of the case, they included many of the Email: [email protected] principals involved in the Grand Bargain. Website: cppp.usc.edu An electronic copy of the case can be downloaded Copyright ©2017 by on The Center’s website at cppp.usc.edu. -

Working Together

2016 LEGAL AID ANNUAL REPORT WORKING TOGETHER Expanding impact with community partnerships 2016 MID-MINNESOTA LEGAL AID BOARD Robert A. McLeod, President Sara McGrane, First Vice President Larry N. Jensen, Second Vice President Eric Rucker, Past President Timothy M. Kelley, Treasurer Cathy Haukedahl, Secretary Shari Aberle Stan Alleyne Jorge Arrellano Patrick M. Arenz Andrew M. Carlson Michael Elliott Michael T. Feichtinger Anna K.B. Finstrom Brigid Fitzgerald Julie Kisner Thomas G. Kramer Dorraine A. Larison John P. Mandler David M. March Sue McGuigan Nataisia McRoy Rebecca Nathan Christopher R. Smith Rachna Sullivan Mai Thor Kimberly Washington DEAR FRIENDS, In 1913, Legal Aid opened its doors with one attorney, who quickly had more work than he could handle. A partnership with the newly-founded University of Minnesota Law School Clinic expanded services and opportunities for clients, law students and Legal Aid, beginning our tradition of working with partners in our community. We thank you for being among our most important partners. We appreciate your financial and volunteer support as we seek new ways to ensure the laws work as they were meant to, protecting the rights of Minnesotans regardless of financial resources. Now more than ever, partnerships are fundamental to Legal Aid’s impact. our To advocate for In this report, you’ll read about collaborations across the spec- mission the legal rights trum of our work, from well-established community clinics to of disadvantaged brand new partnerships in cooperation with various neighbor- hood organizations to meet specific needs. people to have safe, healthy and We have intentionally developed new strategies for meeting our clients where they go in their every-day life to solve their prob- independent lems — the doctor, neighborhood organizations, domestic violence lives in strong shelters and government offices. -

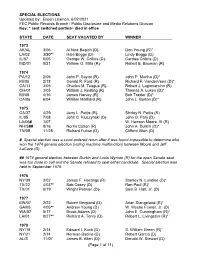

Special Election Dates

SPECIAL ELECTIONS Updated by: Eileen Leamon, 6/02/2021 FEC Public Records Branch / Public Disclosure and Media Relations Division Key: * seat switched parties/- died in office STATE DATE SEAT VACATED BY WINNER 1973 AK/AL 3/06 Al Nick Begich (D)- Don Young (R)* LA/02 3/20** Hale Boggs (D)- Lindy Boggs (D) IL/07 6/05 George W. Collins (D)- Cardiss Collins (D) MD/01 8/21 William O. Mills (R)- Robert E. Bauman (R) 1974 PA/12 2/05 John P. Saylor (R)- John P. Murtha (D)* MI/05 2/18 Gerald R. Ford (R) Richard F. VanderVeen (D)* CA/13 3/05 Charles M. Teague (R)- Robert J. Lagomarsino (R) OH/01 3/05 William J. Keating (R) Thomas A. Luken (D)* MI/08 4/16 James Harvey (R) Bob Traxler (D)* CA/06 6/04 William Mailliard (R) John L. Burton (D)* 1975 CA/37 4/29 Jerry L. Pettis (R)- Shirley N. Pettis (R) IL/05 7/08 John C. Kluczynski (D)- John G. Fary (D) LA/06# 1/07 W. Henson Moore, III (R) NH/S## 9/16 Norris Cotton (R) John A. Durkin (D)* TN/05 11/25 Richard Fulton (D) Clifford Allen (D) # Special election was a court-ordered rerun after it was found impossible to determine who won the 1974 general election (voting machine malfunction) between Moore and Jeff LaCaze (D). ## 1974 general election between Durkin and Louis Wyman (R) for the open Senate seat was too close to call and the Senate refused to seat either candidate. Special election was held in September 1975. -

Mn 2000 MAPS 01133.Pdf (526.3Kb Application/Pdf)

: • • ," ·, .•• > ••• ~· ; ~ : l I / ,.' ._. DIRECTORY MINNESOTA STATE & FEDERAL LEGISLATORS 1975 (J\ jl,\ ! Ii l: ("C.., Cifd t x'.k/n~.; o ;, ::.~ l :, '• ..'.C published as a public service by (g) ~JN NlS OIA AN-4\_LYSIS & PLANNING SYSJ_EM. AG RIC UL TURAL EXTENSION SERVICE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA ,,~7 ST. PAUL, MN 55108 --?- ;1115(1,,,,. > Ir' 1 "-,.--,:, ::__ I c1 "' .,- DIREC~ORY MINNESOTA STATE and FEDERAL LEGISLATORS This Directory was prepared by the staff of the Minnesota Analysis and Plan ning System (MAPS), which is part of the Agricultural Extension Service, University of Minnesota. Informational input for the Directory was acquired from legislative off ices and individual members of the legislature. Costs of preparation and publication have been borne by MAPS and any changes, additions, or corrections should be sent to MAPS at the address listed below. Single copies of the Directory will be sent free of charge to individuals re questing them as long as the supply lasts. MAPS cannot honor requests for free mul tiple copies to organizations, but will consider such orders on a cost-reimburse ment basis. Further information can be obtained by contacting: Minnesota Analysis and Planning System (MAPS) 415 Coffey Hall University of Minnesota St. Paul, MN 55108 Ph. (612) 376-7003 i. District ~ ~ ~ FITZSIMONS 19 ANDERSON lA BRAUN 19A CLAWSON lB CORBID 19B MANGAN 2 MOE 20 JOSEFSON 2A KELLY 20A SMOGARD 2B EKEN 20B STANTON J ARNOLD 21 OLSON JA ANDERSON 21A LINDSTROM JB PRAHL 21B SETZEPPANDT 4 WILLET 22 BERNHAGEN 4A ONGE 22A KVAM 4B SHERWOOD 22B DAHL s PERPICH 2J RENNEKE SA FU GINA 2JA ALBRECHT SB SPANISH 2JB JOHNSON 6 PERPICH 24 PURFEERST 6A BEGICH 24A VANASEK 6B JOHNSON 24B BIRNSTIHL 7 SOLON 2S CONZEMIUS 7A MUNGER 25A WHITE 7B JAROS 2SB SCHULZ B DOTY 26 OLSON BA DOTY 26A MENNING BB ULLAND 26B ERICKSON 9 SILLERS 27 OLSON 9A BEAUCHAMP 27A MANN 98 LANGSETH 278 PETERSON 10 HANSON 2B JENSEN lOA DEGROAT 2BA ESAU 108 GRABA 288 ECKSTEIN 11 OLHOFr 29 UELAND, JR. -

Prioritizing-Place-A

The Center on Philanthropy & Public Policy Sol Price Center for Social Innovation PrioritizingPlace A National Forum on Place-Based Initiatives December 4 – 5, 2014 Davidson Conference Center University of Southern California Sol Price School of Public Policy Forum Sponsors Welcome Dear Colleague, We are delighted you could join us for Prioritizing Place: A National Forum on Place-Based Initiatives. This gathering is the culmination of a year-long inquiry into the state of philanthropic initiatives and public sector efforts to address geographically-concentrated poverty, undertaken by The Center on Philanthropy and Public Policy and the Sol Price Center for Social Innovation. This inquiry has provided an opportunity to step back and take a thoughtful look at the experience of place-based initiatives – whether undertaken by philanthropy or government or a combination of the sectors. We hope that this forum helps to elevate the dialogue above specific best practices or discussions about what works to embrace the larger significance and longevity of place-based as a strategy for the field, and that the insights generated over these two days will be useful to philanthropic and public decision makers as they chart their strategies for moving forward. Our effort has been spearheaded by Elwood Hopkins of Emerging Markets. We have been guided by a first-rate national advisory board. Based on their advice and recommendations, we framed the intellectual agenda for this inquiry and identified leading experts to participate in five small and focused discussions – held in Los Angeles, New York, and Washington, D.C. from April to June 2014 – addressing a different aspect of place-based work. -

Tobacco Industry in Transition the Tobacco Industry in Transition

•i_r, _ : #w .1o nt. Md' rYrM$ ! i 1ip1 ' _f awret ysrswldsw ° . :' ! • '; : a 1 : I The Tobacco Industry in Transition The Tobacco Industry in Transition Policies for the 1980s Edited by William R. Finger North Carolina Center for Public Policy Research, Inc. LexingtonBooks D.C. Heath and Company Lexington, Massachusetts Toronto Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Main entry under title: The Tobacco industry in transition. 1. Tobacco manufacture and trade-Government policy-United States. 2. Tobacco manufacture and trade-United States. I. Finger, William R. II. North Carolina Center for Public Policy Research. HD9136.T6 338.1'7371'0973 81-47064 ISBN 0-669-04552-7 AACR2 Copyright © 1981 by North Carolina Center for Public Policy Research, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmit- ted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Published simultaneously in Canada Printed in the United States of America International Standard Book Number: 0-669-04552-7 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 81-47064 Contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction William R. Finger Xi Part I The Tobacco Program and the Farmer 1 Chapter 1 Early Efforts to Control the Market-And Why They Failed Anthony J. Badger 3 Chapter 2 The Federal Tobacco Program: How It Works and Alternatives for Change Charles Pugh 13 Chapter 3 Landmarks in the Tobacco Program Charles Pugh 31 Chapter