The American Shotgun House: a Study of Its Evolution and the Enduring Presence of the Vernacular in American Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Design Forward, Reverse Engineer

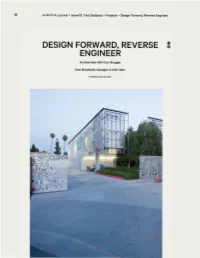

A+R+P+A Journal > Issue 01, Test Subjects> Projects > Design Forward, Reverse Engineer 0 DESIGN FORWARD, REVERSE 0 ENGINEER An interview with Cory Brugger How Morphosis manages to take risks. Published June 23, 2014 Morphosis office In Culver City. Photo: lwan Baan. Thorn Mayne's firm Morphosis has famously roused the ambitions of clients typically reluctant to take risks-even with government agencies such as the General Services Administration (GSA). ARPA .Journal spoke with Cory Brugger at Morphosis to see how the office uses practice as a site for experimentation. As Director of Design Technology, Cory tests ways to leverage technology for the practice, from parametrics to materials prototyping. Editor Janette Kim asked him how ideas about research have emerged within the methods, techniques, and processes of production at Morphosis. Janette Kim: What is the role of research at Morphosis? Cory Brugger: As a small practice (we still run like a ma-and-pa shop), we have been able to stay process-oriented, with small agile teams and Thorn involved throughout the entire project. In the evolution of the practice, design intent has always driven our projects. We start with a concept that evolves relative to the context (social, pragmatic, tectonic, etc.) of the project. R&D isn't something we're setting aside budgets for, but rather something that's always inherent and central to our design process. We find opportunities to explore technology, materials, construction, fabrication techniques, or whatever may be needed to realize the unique goals of each project. JK: This is exactly why I thought of Morphosis for this issue of ARPA .Journal. -

Bloomberg Center Design Fact Sheet

SEPTEMBER 13, 2017 Bloomberg Center Design Fact Sheet 02 PRESS RELEASE 05 ABOUT MORPHOSIS 06 BIOGRAPHY OF THOM MAYNE 07 ABOUT CORNELL TECH 08 PROJECT INFORMATION 09 PROJECT CREDITS 11 PROJECT PHOTOS 13 CONTACT 1 Bloomberg Center Press Release// The Bloomberg Center at Cornell Tech Designed by Morphosis Celebrates Formal Opening Innovative Building is Academic Hub of New Applied Science Campus with Aspiration to Be First Net Zero University Building in New York City NEW YORK, September 13, 2017 – Morphosis Architects today marked the official opening of The Emma and Georgina Bloomberg Center, the academic hub of the new Cornell Tech campus on Roosevelt Island. With the goal of becoming a net zero building, The Bloomberg Center, designed by the global architecture and design firm, forms the heart of the campus, bridging academia and industry while pioneering new standards in environmental sustainability through state-of- the-art design. Spearheaded by Morphosis’ Pritzker Prize-winning founder Thom Mayne and principal Ung-Joo Scott Lee, The Bloomberg Center is the intellectual nerve center of the campus, reflecting the school’s joint goals of creativity and excellence by providing academic spaces that foster collective enterprise and collaboration. “The aim of Cornell Tech to create an urban center for interdisciplinary research and innovation is very much in line with our vision at Morphosis, where we are constantly developing new ways to achieve ever-more-sustainable buildings and to spark greater connections among the people who use our buildings. With the Bloomberg Center, we’ve pushed the boundaries of current energy efficiency practices and set a new standard for building development in New York City,” said Morphosis founder and design director Thom Mayne. -

Historic District Design Guidelines 07

CALHOUN, GEORGIA - HISTORIC DISTRICT DESIGN GUIDELINES 07 Handbook for Owners, Residents, and the Historic Preservation Commission CALHOUN GA INCLUDES INTRODUCTION AND APPENDIX WITH: • Glossary • Secretary of the Interiorʼs Standards for Rehabilitation • Official Calhoun Historic District Ordinance • HPC Rules for Procedure • Resources for Assistance Designed By: Prepared For: The Calhoun Historic Preservation Commission June, 2007 CALHOUN, GEORGIA - HISTORIC DISTRICT DESIGN GUIDELINES 07 Handbook for Owners, Residents, and the Historic Preservation Commission Prepared For: • Calhoun Historic Preservation Commission • City of Calhoun • Calhoun Main Street June, 2007 Designed By: MACTEC Engineering and Consulting, Inc. 396 Plasters Avenue Atlanta, Georgia 30324 404.873.4761 Project 6311-06-0054 HANDBOOK TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1 OVERVIEW CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION CHAPTER 4. COMMERCIAL ARCHITECTURAL GUIDELINES 1.1. Why Have Guidelines? . .1-1 4.1. Storefronts . .2-9 1.2. Calhoun Historic District Map . .1-1 • General Standards 1.3. Retaining a “Sense of Place” . .1-2 • Entrances and Plans . .2-10 1.4. Recognize Change . .1-3 • Doors • Displays . .2-11 CHAPTER 2. HOW TO USE THESE GUIDELINES • Transom Windows . .2-12 2.1. Project Planning and Preservation Principles . .1-4 • Bulkheads . .2-13 • Principle Preservation Methods • Store Cornices / Belt Course / Sign Band . .2-14 • The Secretary of the Interiorsʼ Standards 4.2. Upper Façades . .2-15 2.2. The Historic Preservation Commission (HPC) . .1-6 • Upper Windows 2.3. Relationship to Zoning . .1-7 • Attached Upper Cornices . .2-16 2.4. Design Review Process Flowchart . .1-8 • Roofs . .2-17 1. Materials 2. Parapet Walls 4.3. Rear Façades . .2-18 • Retain Context of the Rear Elevation SECTION 2 • Rear Utilities . -

The Things They've Done : a Book About the Careers of Selected Graduates

The Things They've Done A book about the careers of selected graduates ot the Rice University School of Architecture Wm. T. Cannady, FAIA Architecture at Rice For over four decades, Architecture at Rice has been the official publication series of the Rice University School of Architecture. Each publication in the series documents the work and research of the school or derives from its events and activities. Christopher Hight, Series Editor RECENT PUBLICATIONS 42 Live Work: The Collaboration Between the Rice Building Workshop and Project Row Houses in Houston, Texas Nonya Grenader and Danny Samuels 41 SOFTSPACE: From a Representation of Form to a Simulation of Space Sean tally and Jessica Young, editors 40 Row: Trajectories through the Shotgun House David Brown and William Williams, editors 39 Excluded Middle: Toward a Reflective Architecture and Urbanism Edward Dimendberg 38 Wrapper: 40 Possible City Surfaces for the Museum of Jurassic Technology Robert Mangurian and Mary-Ann Ray 37 Pandemonium: The Rise of Predatory Locales in the Postwar World Branden Hookway, edited and presented by Sanford Kwinter and Bruce Mau 36 Buildings Carios Jimenez 35 Citta Apperta - Open City Luciano Rigolin 34 Ladders Albert Pope 33 Stanley Saitowitz i'licnaei Bell, editor 26 Rem Koolhaas: Conversations with Students Second Editior Sanford Kwinter, editor 22 Louis Kahn: Conversations with Students Second Edition Peter Papademitriou, editor 11 I I I I I IIII I I fo fD[\jO(iE^ uibn/^:j I I I I li I I I I I II I I III e ? I I I The Things They've DoVie Wm. -

Map-Print.Pdf

MAP .................................................... page TOUR 1 .................................................... page TOUR 2 .................................................... page TOUR 3 .................................................... page TOUR 4 .................................................... page TOUR 5 .................................................... page TOUR 6 .................................................... page TOUR 7 .................................................... page TOUR 8 .................................................... page TOUR 9 .................................................... page jodi summers Sotheby’s International realty 310.392.1211 jodi summers Sotheby’s International realty 310.392.1211 Tour 1 - Adelaide Drive - ¾ mile distance Adelaide Drive is located at the Santa Monica Canyon rim and forms the Northern Boundary of the City and features majestic canyon views. Since the turn of the 20th Century, this street has attracted numerous prominent southern Californians. This street is named after Robert Gillis’ daughter, Adelaide. Robert Gillis was the owner of the Santa Monica Land and Water Co. and bought thousands of acres in the Palisades in the 1880s. In 1923, Gillis sold 22,000 acres to Alphonso Bell, who developed Bel Air, and went on to develop the Pacific Palisades. 6. Worrell “Zuni House,” 1923-24 710 Adelaide Pl. Architect Robert Stacey-Judd is best known for his Mayan-themed architecture, as is evident in the Pueblo Revival style home, the only known example of his work in Santa Monica. The design of the house embodies many of the character-defining features of the Pueblo Revival style, including an asymmetrical facade, block composition, and flat roofs with parapets highlighted by red tile coping. Noteworthy are projecting roof beams (a.k.a. vigas) typical of the Zuni tribe of Arizona Indians. The rounded corners of the terraced walls, simulate adobe. A stepped Mayan motif is repeated in the door and window frames. It’s said that the work of this architect "is always a surprise.” 7. -

Tear It Down! Save It! Preservationists Have Gained the Upper Hand in Protecting Historic Buildings

Tear It Down! Save It! Preservationists have gained the upper hand in protecting historic buildings. Now the ques- tion is whether examples of modern architecture— such as these three buildings —deserve the same respect as the great buildings of the past. By Larry Van Dyne The church at 16th and I streets in downtown DC does not match the usual images of a vi- sually appealing house of worship. It bears no resemblance to the picturesque churches of New England with their white clapboard and soaring steeples. And it has none of the robust stonework and stained-glass windows of a Gothic cathedral. The Third Church of Christ, Scientist, is modern architecture. Octagonal in shape, its walls rise 60 feet in roughcast concrete with only a couple of windows and a cantilevered carillon interrupting the gray façade. Surrounded by an empty plaza, it leaves the impression of a supersized piece of abstract sculpture. The church sits on a prime tract of land just north of the White House. The site is so valua- ble that a Washington-based real-estate company, ICG Properties, which owns an office building next door, has bought the land under the church and an adjacent building originally owned by the Christian Science home church in Boston. It hopes to cut a deal with the local church to tear down its sanctuary and fill the assembled site with a large office complex. The congregation, which consists of only a few dozen members, is eager to make the deal — hoping to occupy a new church inside the complex. -

AIA LA Advocacy Platform

DESIGN- THINKING & REGIONAL AWARENESS The AIA LA advocacy platform AIA LA Our Challenges, Our Strengths Southern s a region, we have the best weather, the Awonderful and varied natural terrain and California some of the most creative and diverse people on the planet. It’s important to celebrate LA’s is an idyllic beauty and grace as often, as loudly and as clearly as we can. However, we’re also the place. hotbed for almost every physical, natural and human-made challenge the world has to offer including climate change, severe drought, an aging infrastructure, unaffordable housing, a concrete and treeless environment and, much of the time, unforgiving traffic as well as being in a region prone to earthquakes. Let’s face it. We don’t really have the money, the time and seldom do we seem to have a system in place that has the social and political capital necessary to engage and solve these issues and yet we know we can take on these challenges. A prime example of this is measure R that is making major inroads into our transportation network, so we know we can do it. However continuing to do business as usual - attempting to solve these vast and substantial problems in isolation from each other – will only yield marginal results, at best. By learning to ask better questions, and focusing our efforts on the future we’d like to see how we, as a region, could work together to identify more effective and aspirational solutions. As Architects we are accustomed to integrating complex criteria from multiple disciplines to elicit elegant solutions that satisfy fiscal, social and functional issues. -

Design for What Matters

PAU Fair Housing Act Updates architectmagazine.com Bryony Roberts Ponti’s Denver Art Museum Reborn The Journal of The American Paul Andersen Deryl McKissack Has Seen It All Institute of Architects Design for What Matters The 2021 P/A Award winners care about community and context Flawless—Just As You Intended Keep your envelope design intact from your desk to the jobsite with DensElement® Barrier System. Eliminate WRB-AB design variability and installation inconsistencies, which can degrade your design. By filling microscopic voids in the glass mat and gypsum core via AquaKor™ Technology, a hydrophobic, monolithic surface is created that blocks bulk water while retaining vapor permeability. And with cladding versatility, you can design with nearly any cladding type. Control? With DensElement® Barrier System, it always stays in your hands. Future Up. Visit DensElement.com ©2021 GP Gypsum LLC. All rights reserved. Unless otherwise noted, all trademarks are owned by or licensed to GP Gypsum LLC. Simplified— Just as you requested Introducing DensDefy™ Accessories Specify DensDefy™ Accessories as part of the DensElement® Barrier System to deliver a complete, tested solution for providing water-control continuity—all supported by a Georgia-Pacific warranty. DensDefy™ Liquid Flashing finishes DensElement® Barrier System by blocking bulk water at the seams, fasteners and rough openings, while DensDefy™ Transition Membrane covers all material transitions and areas of movement. You could call it integrated- plus; we just call it simplicity at work. For more information, visit DensDefy.com. ©2021 GP Gypsum LLC. All rights reserved. Unless otherwise noted, all trademarks are owned by or licensed to GP Gypsum LLC. -

The Future of Knoxville's Past

Th e Future of Knoxville’s Past Historic and Architectural Resources in Knoxville, Tennessee Knoxville Historic Zoning Commission October 2006 Adopted by the Knoxville Historic Zoning Commission on October 19, 2006 and by the Knoxville-Knox County Metropolitan Planning Commission on November 9, 2006 Prepared by the Knoxville-Knox County Metropolitan Planning Commission Knoxville Historic Zoning Commissioners J. Nicholas Arning, Chairman Scott Busby Herbert Donaldson L. Duane Grieve, FAIA William Hoehl J. Finbarr Saunders, Jr. Melynda Moore Whetsel Lila Wilson MPC staff involved in the preparation of this report included: Mark Donaldson, Executive Director Buz Johnson, Deputy Director Sarah Powell, Graphic Designer Jo Ella Washburn, Graphic Designer Charlotte West, Administrative Assistant Th e report was researched and written by Ann Bennett, Senior Planner. Historic photographs used in this document are property of the McClung Historical Collection of the Knox County Public Library System and are used by MPC with much gratitude. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction . .5 History of Settlement . 5 Archtectural Form and Development . 9 Th e Properties . 15 Residential Historic Districts . .15 Individual Residences . 18 Commercial Historic Districts . .20 Individual Buildings . 21 Schools . 23 Churches . .24 Sites, Structures, and Signs . 24 Property List . 27 Recommenedations . 29 October 2006 Th e Future Of Knoxville’s Past INTRODUCTION that joined it. Development and redevelopment of riverfront In late 1982, funded in part by a grant from the Tennessee sites have erased much of this earlier development, although Historical Commission, MPC conducted a comprehensive there are identifi ed archeological deposits that lend themselves four-year survey of historic sites in Knoxville and Knox to further study located on the University of Tennessee County. -

Lorcan O'herlihy,Faia a Distinguished Practice

Since founding his firm in 1994, Lorcan O’Herlihy, FAIA has utilized LORCAN architecture as a catalyst of change to shape and enrich the complex, O’HERLIHY,FAIA urban landscape of our contemporary city. The work of his firm, Lorcan O’Herlihy Architects (LOHA), is guided by a conscious understanding that A DISTINGUISHED architecture operates within a layered context of political, developmental, environmental, and social structures. With studios in Los Angeles and PRACTICE Detroit, LOHA has built over 90 projects across three continents. O’Herlihy and LOHA have produced work that has been published in over 20 countries and received over 100 awards throughout the years including the AIA Los Angeles firm of the year. The diverse work of the firm ranges from art galleries, bus shelters, and large-scale neighborhood plans, to large mixed-use developments, housing developments, and university residential complexes. Each project by LOHA exhibits O’Herlihy’s belief that artistry and bold design are key to building a vibrant, social space to elevate the human condition via the built environment. MARIPOSA1038 SL11024 BIG BLUE BUS STOPS O’Herlihy spent his formative years working at I.M. Pei Partners in New York and Paris on the addition to the Grand Louvre Museum. The LORCAN experience working on a project that harmoniously coupled art and O’HERLIHY,FAIA architecture was paramount to his design philosophy and installed a passion for aesthetic improvisation and composition. In addition, O’Herlihy A DISTINGUISHED also worked as a painter, sculptor, and furniture maker. The breath of scales—from being part of a design team for a large public art institution PRACTICE like the Louvre to intimately producing art and objects—melds his inclination for material exploration and formal inflection which form the basis of his eponymous firm, Lorcan O’Herlihy Architects [LOHA]. -

List of House Types

List of house types This is a list of house types. Houses can be built in a • Assam-type House: a house commonly found in large variety of configurations. A basic division is be- the northeastern states of India.[2] tween free-standing or Single-family houses and various types of attached or multi-user dwellings. Both may vary • Barraca: a traditional style of house originated in greatly in scale and amount of accommodation provided. Valencia, Spain. Is a historical farm house from the Although there appear to be many different types, many 12th century BC to the 19th century AD around said of the variations listed below are purely matters of style city. rather than spatial arrangement or scale. Some of the terms listed are only used in some parts of the English- • Barndominium: a type of house that includes liv- speaking world. ing space attached to either a workshop or a barn, typically for horses, or a large vehicle such as a recreational vehicle or a large recreational boat. 1 Detached single-unit housing • Bay-and-gable: a type of house typically found in the older areas of Toronto. Main article: Single-family detached home • Bungalow: any simple, single-storey house without any basement. • A-frame: so-called because of the appearance of • the structure, namely steep roofline. California Bungalow • Addison house: a type of low-cost house with metal • Cape Cod: a popular design that originated in the floors and cavity walls made of concrete blocks, coastal area of New England, especially in eastern mostly built in the United Kingdom and in Ireland Massachusetts. -

Digitally Fabricated LOW-COST HOUSING Material, Joint and Prototype

Department of Civil, Building and Environmental Engineering PhD in Architectural Engineering and Urban Planning Curriculum Building Architecture Cycle XXIX Doctoral Dissertation Digitally Fabricated LOW-COST HOUSING Material, Joint and Prototype By: Kareem Elsayed Supervisor Professor Antonio Fioravanti June 2017 ii Dipartimento di Ingegneria Civile, Edile e Ambientale Dottorato in Ingegneria dell'Architettura e dell'Urbanistica Curriculum Edile Architettura XXIX ciclo Dottorato di Ricerca Fabbricazione Digitale nella produzione di ALLOGGI A BASSO COSTO Materiale, giunto e prototipo Da: Kareem Elsayed Supervisore Professore Antonio Fioravanti Giugno 2017 iii iv Contents Acknowledgments .................................................................................................................................................... viii Abstract ............................................................................................................................................................................ xi 1 CHAPTER 1 | Introduction ................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Problem definition ......................................................................................................................................... 2 1.2 Research questions ........................................................................................................................................ 4 1.3 Aims and objectives ......................................................................................................................................