Downloaded27 from Brill.Com09/29/2021 10:35:02PM Via Free Access 78 Ji

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Misrepresentation of Representation: in Defense of Regional Storytelling in Netflix's the New Legends of Monkey

The Misrepresentation of Representation: In Defense of Regional Storytelling in Netflix’s The New Legends of Monkey KATE MCEACHEN The 2018 Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC Me), Television New Zealand (TVNZ), and Netflix’s coproduction of the original series The New Legends of Monkey (2018) is a fantasy-based television series that reimagines Monkey (1978), a British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) dubbing of the Japanese television series Saiyūki 西遊記. Saiyūki was an adaptation of the historically significant Chinese novel Xiyou ji (Wu Cheng’en, 1592), known in English as Journey to the West. Monkey gained a cult following in Australia, New Zealand, and other international markets leading to the 2018 reboot The New Legends of Monkey, which, unlike Monkey, was released in the United States (Flanagan). This new iteration prompted cultural confusion from those largely unfamiliar with the preceding series, the contexts in which it was introduced to English-speaking viewers in Australia and New Zealand, or the cult response that resulted. This article presents the recent series with this background in mind and within the context of locally produced television in New Zealand, where The New Legends of Monkey was filmed. Analysis of online discussions exposes the interpretive differences arising from this lack of context regarding the show’s connection to Monkey and highlights the problems viewers face interpreting stories outside of their local production markets—an increasingly relevant problem as more regional productions become accessible to a wide range of audiences through transnational streaming services like Netflix. The 2018 The New Legends of Monkey television adaptation, produced by and for the Australian and New Zealand markets and co-produced for international KATE MCEACHEN is currently pursuing her Doctoral Degree in Cultural Studies at The University of Southern Queensland in Australia. -

Archiving Movements: Short Essays on Materials of Anime and Visual Media V.1

Contents Exhibiting Anime: Archive, Public Display, and the Re-narration of Media History Gan Sheuo Hui ………… 2 Utilizing the Intermediate Materials of Anime: Royal Space Force: The Wings of Honnêamise Ishida Minori ………… 17 The Film through the Archive and the Archive through the Film: History, Technology and Progress in Royal Space Force: The Wings of Honnêamise Dario Lolli ………… 25 Interview with Yamaga Hiroyuki, Director of Royal Space Force: The Wings of Honnêamise What Do Archived Materials Tell Us about Anime? Kim Joon Yang ………… 31 Exhibiting Manga: Impulses to Gain from the Archiving/Unearthing Anime Project Jaqueline Berndt ………… 36 Analyzing “Regional Communities” with “Visual Media” and “Materials” Harada Ken’ichi ………… 41 About the Archive Center for Anime Studies in Niigata University ………… 45 Exhibiting Anime: Archive, Public Display, and the Re-narration of Media History Gan Sheuo Hui presumably, the majority are in various storage Background of the Project places after their production cycles. It is not The exhibition “A World is Born: The uncommon that they are forgotten, displaced or Emerging Arts and Designs in 1980s Japanese eventually discarded due to the expenses incurred Animation” (19-31 March 2018) hosted at DECK, for storage. In many ways, these materials an independent art space in Singapore, is encompass an often forgotten yet significant part of an ongoing research collaboration research resource essential for understanding between the researchers from Puttnam School key aspects of Japanese animation production of Film and Animation in Singapore and the cultures and practices. Archive Center for Anime Studies in Niigata “A World is Born” was an exhibition focusing University (ACASiN). -

Images of Women in Chinese Literature. Volume 1. REPORT NO ISBN-1-880938-008 PUB DATE 94 NOTE 240P

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 385 489 SO 025 360 AUTHOR Yu-ning, Li, Ed. TITLE Images of Women in Chinese Literature. Volume 1. REPORT NO ISBN-1-880938-008 PUB DATE 94 NOTE 240p. AVAILABLE FROM Johnson & Associates, 257 East South St., Franklin, IN 46131-2422 (paperback: $25; clothbound: ISBN-1-880938-008, $39; shipping: $3 first copy, $0.50 each additional copy). PUB TYPE Books (010) Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Chinese Culture; *Cultural Images; Females; Folk Culture; Foreign Countries; Legends; Mythology; Role Perception; Sexism in Language; Sex Role; *Sex Stereotypes; Sexual Identity; *Womens Studies; World History; *World Literature IDENTIFIERS *Asian Culture; China; '`Chinese Literature ABSTRACT This book examines the ways in which Chinese literature offers a vast array of prospects, new interpretations, new fields of study, and new themes for the study of women. As a result of the global movement toward greater recognition of gender equality and human dignity, the study of women as portrayed in Chinese literature has a long and rich history. A single volume cannot cover the enormous field but offers volume is a starting point for further research. Several renowned Chinese writers and researchers contributed to the book. The volume includes the following: (1) Introduction (Li Yu- Wing);(2) Concepts of Redemption and Fall through Woman as Reflected in Chinese Literature (Tsung Su);(3) The Poems of Li Qingzhao (1084-1141) (Kai-yu Hsu); (4) Images of Women in Yuan Drama (Fan Pen Chen);(5) The Vanguards--The Truncated Stage (The Women of Lu Yin, Bing Xin, and Ding Ling) (Liu Nienling); (6) New Woman vs. -

Essays on Monkey: a Classic Chinese Novel Isabelle Ping-I Mao University of Massachusetts Boston

University of Massachusetts Boston ScholarWorks at UMass Boston Critical and Creative Thinking Capstones Critical and Creative Thinking Program Collection 9-1997 Essays on Monkey: A Classic Chinese Novel Isabelle Ping-I Mao University of Massachusetts Boston Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.umb.edu/cct_capstone Recommended Citation Ping-I Mao, Isabelle, "Essays on Monkey: A Classic Chinese Novel" (1997). Critical and Creative Thinking Capstones Collection. 238. http://scholarworks.umb.edu/cct_capstone/238 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Critical and Creative Thinking Program at ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. It has been accepted for inclusion in Critical and Creative Thinking Capstones Collection by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at UMass Boston. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ESSAYS ON MONKEY: A CLASSIC . CHINESE NOVEL A THESIS PRESENTED by ISABELLE PING-I MAO Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies, University of Massachusetts Boston, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS September 1997 Critical and Creative Thinking Program © 1997 by Isabelle Ping-I Mao All rights reserved ESSAYS ON MONKEY: A CLASSIC CHINESE NOVEL A Thesis Presented by ISABELLE PING-I MAO Approved as to style and content by: Delores Gallo, As ciate Professor Chairperson of Committee Member Delores Gallo, Program Director Critical and Creative Thinking Program ABSTRACT ESSAYS ON MONKEY: A CLASSIC CHINESE NOVEL September 1997 Isabelle Ping-I Mao, B.A., National Taiwan University M.A., University of Massachusetts Boston Directed by Professor Delores Gallo Monkey is one of the masterpieces in the genre of the classic Chinese novel. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 329 4th International Conference on Contemporary Education, Social Sciences and Humanities (ICCESSH 2019) A Study of Polysemy and Multi-translation in Tao Te Ching Yan Wang Fuzhou University of International Studies and Trade Fuzhou, China Abstract—Only 5000 words in Tao Te Ching have exhausted all the phenomena in the world. A statistic has been II. SELECTION OF THE TRANSLATED VERSIONS OF TAO made among these 5000 words. Many words are repetitive, TE CHING which shows that a word or a phase has more than one This study chooses the translation versions of Arthur meaning. It has achieved such a profound and magnificent Waley and Gu Zhengkun as the subjects of study. The reason connotation of Tao Te Ching. A thorough study of polysemy is is that they live in different times and represent two different an important prerequisite for the translation of Tao Te Ching to convey its essence well. Therefore, the article screened the cultures of the East and the West. Translation is essentially a polysemy in Tao Te Ching and found many words and phrases process of cultural transmission, and the attributes of culture have more than one meaning. The article chooses “shàng”, will not change with time and space. Therefore, the “xíng”, “shàn” and “qù”, which are polysemous and appear comparison between Chinese and Western versions can frequently, as research objects. It is of great significance to better reveal whether the cultural connotations contained in study the accurate translation of these representative words for Tao Te Ching can be reproduced in the translated version. -

International Reinterpretations

International Reinterpretations 1 Remakes know no borders… 2 … naturally, this applies to anime and manga as well. 3 Shogun Warriors 4 Stock-footage series 5 Non-US stock-footage shows Super Riders with the Devil Hanuman and the 5 Riders 6 OEL manga 7 OEL manga 8 OEL manga 9 Holy cow, more OEL manga! 10 Crossovers 11 Ghost Rider? 12 The Lion King? 13 Godzilla 14 Guyver 15 Crying Freeman 16 Fist of the North Star 17 G-Saviour 18 Blood: the Last Vampire 19 Speed Racer 20 Imagi Studios 21 Ultraman 6 Brothers vs. the Monster Army (Thailand) The Adventure Begins (USA) Towards the Future (Australia) The Ultimate Hero (USA) Tiga manhwa 22 Dragonball 23 Wicked City 24 City Hunter 25 Initial D 26 Riki-Oh 27 Asian TV Dramas Honey and Clover Peach Girl (Taiwan) Prince of Tennis (Taiwan) (China) 28 Boys Over Flowers Marmalade Boy (Taiwan) (South Korea) Oldboy 29 Taekwon V 30 Super Batman and Mazinger V 31 Space Gundam? Astro Plan? 32 Journey to the West (Saiyuki) Alakazam the Great Gensomaden Saiyuki Monkey Typhoon Patalliro Saiyuki Starzinger Dragonball 33 More “Goku”s 34 The Water Margin (Suikoden) Giant Robo Outlaw Star Suikoden Demon Century Akaboshi 35 Romance of the Three Kingdoms (Sangokushi) Mitsuteru Yokoyama’s Sangokushi Kotetsu Sangokushi BB Senshi Sangokuden Koihime Musou Ikkitousen 36 World Masterpiece Theater (23 seasons since 1969) Moomin Heidi A Dog of Flanders 3000 Leagues in Search of Mother Anne of Green Gables Adventures of Tom Sawyer Swiss Family Robinson Little Women Little Lord Fauntleroy Peter -

An Analysis of the English Translation of Li Bai's Poems

International Journal of English, Literature and Social Science (IJELS) Vol-4, Issue-4, Jul – Aug 2019 https://dx.doi.org/10.22161/ijels.4437 ISSN: 2456-7620 An Analysis of the English Translation of Li Bai’s Poems Huang Shanshan1, Wang Feng2 1School of Foreign Studies, Yangtze University, Hubei, 434023 PRC China Email: [email protected] 2School of Foreign Studies, Yangtze University, Hubei, 434023 PRC China Email:[email protected] (correspondence) Abstract— For more than 300 years, Li Bai’s poems have been translated, introduced and disseminated in large quantities, which undoubtedly plays an important role in the out-going of Chinese culture. Based on the general historical context of the English translation of Li Bai’s poems and the collected data about his translations, this study analyses the characteristics of his English translation in different periods and sums up how Li Bai’s poems have claimed the world literary status. Keywords— Li Bai’s poems, English translation, characteristics, the world literary status. I. INTRODUCTION II. In recent years, scholars in China and other countries 2.1 Before the 20th Century: the Initial Stage have become more and more enthusiastic about the As early as the 18th century, there were sporadic records translation of Li Bai’s poems and have made some of the poet Li Bai in the West. Most of these records were achievements. However, the research field is relatively made by missionaries, diplomats or sinologists. It is based isolated, mainly focusing on the translation theory or on these early explorations that the translation and practice, lacking of comprehensive interdisciplinary introduction of Li Bai’s poems can be developed rapidly research. -

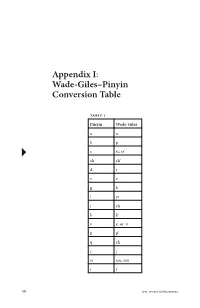

Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table

Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table Table 1 Pinyin Wade-Giles aa bp c ts’, tz’ ch ch’ dt ee gk iyi jch kk’ oe or o pp’ qch rj si ssu, szu tt’ 58 DOI: 10.1057/9781137303394 Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table 59 xhs yi i yu u, yu you yu z ts, tz zh ch zi tzu -i (zhi) -ih (chih) -ie (lie) -ieh (lieh) -r (er) rh (erh) Examples jiang chiang zhiang ch’iang zi tzu zhi chih cai tsai Zhu Xi Chu Hsi Xunzi Hsün Tzu qing ch’ing xue hsüeh DOI: 10.1057/9781137303394 60 Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table Table 2 Wade–Giles Pinyin aa ch’ ch ch j ch q ch zh ee e or oo ff hh hs x iyi -ieh (lieh) -ie (lie) -ih (chih) -i (zhi) jr kg k’ k pb p’ p rh (erh) -r (er) ssu, szu si td t’ t ts’, tz’ c ts, tz z tzu zi u, yu u yu you DOI: 10.1057/9781137303394 Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table 61 Examples chiang jiang ch’iang zhiang ch‘ing qing chih zhi Chu Hsi Zhu Xi hsüeh xue Hsün Tzu Xunzi tsai cai tzu zi DOI: 10.1057/9781137303394 Appendix II: Concordance of Key Philosophical Terms ⠅ai (To love) 1.5, 1.6, 3.17, 12.10, 12.22, 14.7, 17.4, 17.21 (9) 䘧 dao (Way, Path, Road, The Way, To tread a path, To speak, Doctrines, etc.) 1.2, 1.5, 1.11, 1.12, 1.14, 1.15, 2.3, 3.16, 3.24, 4.5, 4.8, 4.9, 4.15, 4.20, 5.2, 5.7, 5.13, 5.16, 5.21, 6.12, 6.17, 6.24, 7.6, 8.4, 8.7, 8.13, 9.12, 9.27, 9.30, 11.20, 11.24, 12.19, 12.23, 13.25, 14.1, 14.3, 14.19, 14.28, 14.36, 15.7, 15.25, 15.29, 15.32, 15.40, 15.42, 16.2, 16.5, 16.11, 17.4, 17.14, 18.2, 18.5, 18.7, 19.2, 19.4, 19.7, 19.12, 19.19, 19.22, 19.25. -

Fiction-2-2018-2.Pdf

Journey the the West (With a Twist) Quarry Bay School, Bratton, Luke - 8 t was a usual evening. Sun Wukong, Zhu Bajie, White Dragon Horse and Tang Sanzang were all happily sitting around the Dining table feasting on a banquet. Everyone was having a good time. They I were telling jokes and reminding everyone about good times. Except for one thing. Zhu Bajie was acting very strangely. He just wasn't being himself. Tang Sanzang seemed to be the only one who noticed Zhu Bajie and his unusual behaviour. As it got late, they all accidentally fell asleep at the table. Sun Wukong was exhausted but just couldn't fall asleep. Out of the darkness, he saw a mysterious figure move around. When it left, Sun Wukong woke up White Dragon Horse and Tang Sanzang but Zhu Bajie was nowhere to be found. Sun Wukong explained everything about how he saw a mysterious shadow and how Zhu Bajie had disappeared. That is when Tang Sanzang joined into the conversation. He told Sun Wukong and White Dragon Horse about how he noticed that Zhu Bajie was acting strangely during dinner. The three of them decided that the next day the second they woke up they were going to search for Zhu Bajie. It was dawn. White Dragon Horse, Tang Sanzang and Sun Wukong set off for their terrific quest. White Dragon Horse agreed to carry all the supplies. Even though they knocked on every door they could find and asked if anyone had seen Zhu Bajie. But the truth fell upon them. -

MANHUA MODERNITY HINESE CUL Manhua Helped Defi Ne China’S Modern Experience

CRESPI MEDIA STUDIES | ASIAN STUDIES From fashion sketches of Shanghai dandies in the 1920s, to phantasma- goric imagery of war in the 1930s and 1940s, to panoramic pictures of anti- American propaganda rallies in the 1950s, the cartoon-style art known as MODERNITY MANHUA HINESE CUL manhua helped defi ne China’s modern experience. Manhua Modernity C TU RE o ers a richly illustrated and deeply contextualized analysis of these il- A lustrations from the lively pages of popular pictorial magazines that enter- N UA D tained, informed, and mobilized a nation through a half century of political H M T and cultural transformation. N H O E A “An innovative reconceptualization of manhua. John Crespi’s meticulous P study shows the many benefi ts of interpreting Chinese comics and other D I M C illustrations not simply as image genres but rather as part of a larger print E T culture institution. A must-read for anyone interested in modern Chinese O visual culture.” R R I CHRISTOPHER REA, author of The Age of Irreverence: A New History A of Laughter in China L N “A rich media-centered reading of Chinese comics from the mid-1920s T U U I I through the 1950s, Manhua Modernity shifts the emphasis away from I R R T T ideological interpretation and demonstrates that the pictorial turn requires T N N examinations of manhua in its heterogenous, expansive, spontaneous, CHINESE CULTURE AND THE PICTORIAL TURN AND THE PICTORIAL CHINESE CULTURE Y and interactive ways of engaging its audience’s varied experiences of Y fast-changing everyday life.” YINGJIN ZHANG, author of Cinema, Space, and Polylocality in a Globalizing China JOHN A. -

Self and Society in Pre-Modern Chinese Literature

Self and Society in Pre-modern Chinese Literature ASIA 3891: Special Topics Fall 2015 MWF 10:10-11:00 Buttrick Hall 250 Prof. Guojun Wang ([email protected]) Office Hours: MW 11:15-12:15 (and by appointment) (Prior knowledge of Chinese language or literature is NOT required) Course Description: How did traditional Chinese people think and write about their selves, society, state, and nature? How have these traditions sustained a millennia-long civilization? How is today’s China connected or severed from its past? And above all, how can we answer these questions through reading Chinese literature? This course is the first of two survey courses on Chinese literature from pre-dynastic to contemporary periods (the second one will be offered in 2016 spring). This ASIA 3891 Self and Society in Pre-modern Chinese Literature 2 course introduces the major intellectual traditions, literary texts, and authors in pre-modern China (ca. 17th century BCE to 13th century CE). The readings follow a chronological order, but in each period we focus on some particular themes about self and society. The central topics include the intersections between literature and history, religion, gender, urban life, and print culture. This introductory course will provide you with a firm grasp of Chinese literary tradition, and prepare you for further studies in Chinese literature and history. Through this course, you will be familiar with China’s intellectual traditions and literary history, hone the skills of close reading, and learn to think and write critically. Class meets three times a week. Each class meeting comprises a 30-minute lecture followed by a 20-minute discussion. -

The Legend of Monkey Comes to Life for ABC, TVNZ and Netflix

Media Release: Thursday April 20, 2017 The Legend of Monkey comes to life for ABC, TVNZ and Netflix New TV series produced by See-Saw Films and Jump Film & TV Production is underway in New Zealand on the major new live action television series The Legend of Monkey, which will premiere on ABC, TVNZ and on Netflix around the world in 2018. Inspired by the 16th Century Chinese fable Journey to the West, the 10-part half hour series follows a teenage girl and a trio of fallen gods on a perilous journey as they attempt to bring an end to a demonic reign of chaos and restore balance to their world. The talented and diverse young cast includes Chai Hansen (Mako Mermaids, The 100) as Monkey, with Luciane Buchanan (Filthy Rich, Blue Rose) playing Tripitaka, Josh Thomson (Terry Teo, 7 Days, The Project) playing Pigsy and Emilie Cocquerel (Lion, An Accidental Soldier) playing Sandy. The series is being filmed at stunning locations in and around Auckland, New Zealand, as well as on spectacular purpose-built sets that bring to life the magical fantasy world our characters inhabit. The Legend of Monkey is being produced for ABC, TVNZ and Netflix by the Oscar and Emmy-winning production company See-Saw Films together with Jump Film & TV. The series is an official New Zealand/Australian co-production with principal investment from Screen Australia in association with Screen NSW, Fulcrum Media Finance and the New Zealand Screen Production Grant. Head writer is the acclaimed Jacquelin Perske (Seven Types of Ambiguity, Spirited, Will) with both Craig Irvin (Nowhere Boys) and Samantha Strauss (Dance Academy) providing additional writing services.