Confucianism.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 329 4th International Conference on Contemporary Education, Social Sciences and Humanities (ICCESSH 2019) A Study of Polysemy and Multi-translation in Tao Te Ching Yan Wang Fuzhou University of International Studies and Trade Fuzhou, China Abstract—Only 5000 words in Tao Te Ching have exhausted all the phenomena in the world. A statistic has been II. SELECTION OF THE TRANSLATED VERSIONS OF TAO made among these 5000 words. Many words are repetitive, TE CHING which shows that a word or a phase has more than one This study chooses the translation versions of Arthur meaning. It has achieved such a profound and magnificent Waley and Gu Zhengkun as the subjects of study. The reason connotation of Tao Te Ching. A thorough study of polysemy is is that they live in different times and represent two different an important prerequisite for the translation of Tao Te Ching to convey its essence well. Therefore, the article screened the cultures of the East and the West. Translation is essentially a polysemy in Tao Te Ching and found many words and phrases process of cultural transmission, and the attributes of culture have more than one meaning. The article chooses “shàng”, will not change with time and space. Therefore, the “xíng”, “shàn” and “qù”, which are polysemous and appear comparison between Chinese and Western versions can frequently, as research objects. It is of great significance to better reveal whether the cultural connotations contained in study the accurate translation of these representative words for Tao Te Ching can be reproduced in the translated version. -

An Analysis of the English Translation of Li Bai's Poems

International Journal of English, Literature and Social Science (IJELS) Vol-4, Issue-4, Jul – Aug 2019 https://dx.doi.org/10.22161/ijels.4437 ISSN: 2456-7620 An Analysis of the English Translation of Li Bai’s Poems Huang Shanshan1, Wang Feng2 1School of Foreign Studies, Yangtze University, Hubei, 434023 PRC China Email: [email protected] 2School of Foreign Studies, Yangtze University, Hubei, 434023 PRC China Email:[email protected] (correspondence) Abstract— For more than 300 years, Li Bai’s poems have been translated, introduced and disseminated in large quantities, which undoubtedly plays an important role in the out-going of Chinese culture. Based on the general historical context of the English translation of Li Bai’s poems and the collected data about his translations, this study analyses the characteristics of his English translation in different periods and sums up how Li Bai’s poems have claimed the world literary status. Keywords— Li Bai’s poems, English translation, characteristics, the world literary status. I. INTRODUCTION II. In recent years, scholars in China and other countries 2.1 Before the 20th Century: the Initial Stage have become more and more enthusiastic about the As early as the 18th century, there were sporadic records translation of Li Bai’s poems and have made some of the poet Li Bai in the West. Most of these records were achievements. However, the research field is relatively made by missionaries, diplomats or sinologists. It is based isolated, mainly focusing on the translation theory or on these early explorations that the translation and practice, lacking of comprehensive interdisciplinary introduction of Li Bai’s poems can be developed rapidly research. -

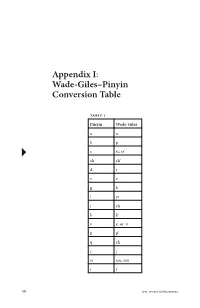

Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table

Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table Table 1 Pinyin Wade-Giles aa bp c ts’, tz’ ch ch’ dt ee gk iyi jch kk’ oe or o pp’ qch rj si ssu, szu tt’ 58 DOI: 10.1057/9781137303394 Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table 59 xhs yi i yu u, yu you yu z ts, tz zh ch zi tzu -i (zhi) -ih (chih) -ie (lie) -ieh (lieh) -r (er) rh (erh) Examples jiang chiang zhiang ch’iang zi tzu zhi chih cai tsai Zhu Xi Chu Hsi Xunzi Hsün Tzu qing ch’ing xue hsüeh DOI: 10.1057/9781137303394 60 Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table Table 2 Wade–Giles Pinyin aa ch’ ch ch j ch q ch zh ee e or oo ff hh hs x iyi -ieh (lieh) -ie (lie) -ih (chih) -i (zhi) jr kg k’ k pb p’ p rh (erh) -r (er) ssu, szu si td t’ t ts’, tz’ c ts, tz z tzu zi u, yu u yu you DOI: 10.1057/9781137303394 Appendix I: Wade-Giles–Pinyin Conversion Table 61 Examples chiang jiang ch’iang zhiang ch‘ing qing chih zhi Chu Hsi Zhu Xi hsüeh xue Hsün Tzu Xunzi tsai cai tzu zi DOI: 10.1057/9781137303394 Appendix II: Concordance of Key Philosophical Terms ⠅ai (To love) 1.5, 1.6, 3.17, 12.10, 12.22, 14.7, 17.4, 17.21 (9) 䘧 dao (Way, Path, Road, The Way, To tread a path, To speak, Doctrines, etc.) 1.2, 1.5, 1.11, 1.12, 1.14, 1.15, 2.3, 3.16, 3.24, 4.5, 4.8, 4.9, 4.15, 4.20, 5.2, 5.7, 5.13, 5.16, 5.21, 6.12, 6.17, 6.24, 7.6, 8.4, 8.7, 8.13, 9.12, 9.27, 9.30, 11.20, 11.24, 12.19, 12.23, 13.25, 14.1, 14.3, 14.19, 14.28, 14.36, 15.7, 15.25, 15.29, 15.32, 15.40, 15.42, 16.2, 16.5, 16.11, 17.4, 17.14, 18.2, 18.5, 18.7, 19.2, 19.4, 19.7, 19.12, 19.19, 19.22, 19.25. -

Arthur Waley (1889-1966), Chinese Poetry in Translation

Arthur Waley (1889-1966), Chinese Poetry in Translation John Minford, 5 March 2016 Hang Seng Management College Culture & Translation Series ‘This prince among literati’ — Sacheverell Sitwell 1889: Arthur Waley, born Arthur Schloss to David Frederick Schloss (son of Sigismund Schloss), and Jacob Waley’s older daughter Rachel Sophia. Arthur Schloss’ 1885 article on the Jews of Rumania shows him to have been much in sympathy with the views and interests of Rachel's late father, who was President of the Anglo-Jewish Association. David’s oldest son, Sigismund David, who was born in 1887, later rose to be the second secretary of the Treasury, and was eventually knighted for his services to the British Empire. 1900-1902: Waley attended Lockers Park preparatory school for boys, where Guy Burgess 1911-1963 (also an Apostle, and a Soviet spy) was later also a pupil. 1903-1906: at Rugby School. Arthur left Rugby a year early, in 1906, after a solid classical grounding. He won the Latin Prize and had already earned a classical fellowship at Kings College. 1907-1910: at Cambridge Cambridge Encounters At King’s College in 1907 Waley encountered the Cambridge ‘Apostle’ G E. Moore, with his philosophy of ‘the pleasures of human relationships’. In 1908, Waley delivered a paper to a group including John Maynard Keynes on ‘the passionate love of comrades’. Another important influence was Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson, author of Letters from John Chinaman (1901), who was his tutor at King’s and first introduced him to China. After passing Part 1 of the Classical Tripos exam with a First Class in 1910, Waley spent a year in Germany and France, learning the languages of those countries and gaining reading access to their literatures. -

The Tale of Genji: a Bibliography of Translations and Studies

The Tale of Genji: A Bibliography of Translations and Studies This is intended to be a comprehensive list and thus contains some items that I would not recommend to my students. I should be glad to remedy any errors or omissions. Except for foreign-language translations, the bibliography is restricted to publications in English and I apologize for this limitation. It is divided into the following sub-sections: 1. Translations 2. On Translators and Translations 3. Secondary Sources 4. Genji Art 5. Genji Reception (Noh Drama; Nise Murasaki inaka Genji; Twentieth-century Responses; Secondary Sources) 6. Film, Musical, and Manga Versions GGR, September 2012 1. Translations (arranged in chronological order of publication) 1. Waley, Arthur (1889-1966). The Tale of Genji. 6 vols. London: George Allen and Unwin, 1925-1933.* 2. Benl, Oscar (1914-1986). Die Geschichte vom Prinzen Genji. 2 vols. Zürich: Mannese Verlag, 1966. 3. Ryu Jung 柳呈. Kenji iyagi. 2 vols. Seoul: 乙酉文化社, 1975.** 4. Seidensticker, Edward G. (1921-2007). The Tale of Genji. 2 vols. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1976. 5. Feng Zikai [Hō Shigai] 豊子凱 (1898-1975). Yuanshi wuyu. 3 vols. Beijing, 1980. Originally translated 1961-1965; publication was delayed by the Cultural Revolution, 1966-1976, and the translation finally appeared in 1980. 6. Lin Wen-Yueh [Rin Bungetsu] 林文月. Yüan-shih wu-yü. 2 vols. Taipei, 1982. Originally published 1976-1978. 7. Sieffert, René (1923-2004). Le Dit du Genji. 2 vols. Paris: Publications Orientalistes de France, 1988. Originally published 1977-1985. 8. Sokolova-Deliusina, Tatiana. Povest o Gendzi: Gendzi-monogatari. 6 vols. -

Style, Wit and Word-Play

Style, Wit and Word-Play Style, Wit and Word-Play: Essays in Translation Studies in Memory of David Hawkes Edited by Tao Tao Liu, Laurence K. P. Wong and Chan Sin-wai Style, Wit and Word-Play: Essays in Translation Studies in Memory of David Hawkes, Edited by Tao Tao Liu, Laurence K. P. Wong and Chan Sin-wai This book first published 2012 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2012 by Tao Tao Liu, Laurence K. P. Wong and Chan Sin-wai and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-3571-4, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-3571-8 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE .................................................................................................... vii Tao Tao Liu, Laurence K. P. Wong and Chan Sin-wai INTRODUCTION............................................................................................ ix “STYLE, WIT AND WORD-PLAY” – REMEMBERING DAVID HAWKES (1923-2009) Tao Tao Liu A TRIBUTE TO BROTHER STONE ................................................................... 1 John Minford WHAT IS THE POINT OF MAKING TRANSLATIONS INTO ENGLISH OF CHINESE LITERATURE: RE-EXAMINING ARTHUR WALEY AND DAVID HAWKES ......... 15 Tao Tao Liu SURPRISING THE MUSES: DAVI D HAWKES’ A LITTLE PRIMER OF TU FU ...... 33 Laurence K. P. Wong MIND THE GAP: THE HAWKES-MINFORD TRANSITION IN THE STORY OF THE STONE ..................................................................... 115 Chloë Starr THE TRANSLATOR AS SCHOLAR AND EDITOR: ON PREPARING A NEW CHINESE TEXT FOR THE BILINGUAL THE STORY OF THE STONE ................ -

Eating Murasaki Shikibu Scriptworlds, Reverse-Importation, and the Tale of Genji

Journal of World Literature 1 (2016) 259–274 brill.com/jwl Eating Murasaki Shikibu Scriptworlds, Reverse-Importation, and The Tale of Genji Matthew Chozick University of Birmingham, uk and Temple University, Japan Campus [email protected] Abstract The fifth-century transmission of China’s sophisticated writing system to Japan prompted a cascade of textual and literary developments on the archipelago. Retrofit to support Japanese phonetics and syntax, a hybrid script and literature evolved; from this negotiation of texts emerged Murasaki Shikibu’s The Tale of Genji in eleventh cen- tury Kyoto. While Genji is celebrated today as Japan’s enduring national classic, it fell out of print for much of two centuries preceding its first translation into Victorian era English. This paper examines how interregional exchanges of translations and scripts have amplified the critical and popular success of Genji. It will be argued that English translations of Genji helped to provide a stylistic and typographic model for reintro- ducing the text to modern Japanese readers as a mass-market novel. In theorizing about such matters, the Japanese concept of reverse-importation will be introduced and intercultural transferences are contextualized within Oswald de Andrade’s notion of cultural cannibalism. Keywords Murasaki Shikibu – The Tale of Genji – translation studies – reverse-importation – Japanese literature – Hannibal Lecter … Genji attracts patrons with both the quality and variety of the food on offer with its unique décor. Diners who wish to enjoy the full Japanese experience can reserve the Tatami Room, where the floor is covered in dried rushes, in accordance with the ancient Japanese tradition. -

Heian: a Time and Place

Heian: A Time and Place Ann Jannetta and J. Thomas Rimer The Japanese word "Heian" evokes an image of Japan's history and literature as they developed in this capital city from the eighth to the twelfth century. The name "Heian" means "Peace and Tranquility," words which in fact describe the political order, social stability, and rich cultural development which we now associate with Japan's Heian period. The site of Heian on the Kamo River was chosen by Emperor Kanmu (r. 781-806), who took the bold step of moving the massive imperial bureaucracy to Heian from the former capital at Nara in 794. While earlier capital city sites can be seen scattered over the plains and valleys of Japan's Kansai region, depicting the instability of political power within the imperial court before Emperor Kanmu came to power, the move to Heian would be a permanent one. Heian, now called Kyoto (which means "capital city"), would remain Japan's capital for more than a thousand years. Like Japan's earlier capitals, Heian was built to resemble magnificent Chang'an (present-day Xi'an), the Chinese capital during the Tang dynasty. During the Taika (645-650) and Nara periods (Nara period spanned 710-784), Japanese envoys (called Kentōshi) had visited Tang China and had witnessed its place at the center of Chinese political power and culture. They had returned to Japan and reproduced Changan's layout and architectural features, putting the emperor and his court at the center of Japan's political, religious, and social life. The site of Heian was considered an excellent one for several reasons. -

A Collection of Papers of Arthur Waley and Beryl De Zoete

A COLLECTION OF PAPERS OF ARTHUR WALEY AND BERYL DE ZOETE BY FRANCIS A. JOHNS Bibliographer, Rutgers University Library HE fact that the Library, thanks to the Duncan D. Sutphen and George V. N. Baldwin bequests, recently acquired a Tcollection of books and papers formerly belonging to Arthur Waley and Beryl de Zoete has prompted some requests for a listing of material. As it is not at present possible to produce a detailed inventory, this necessarily brief general description may be helpful and indicative to those interested. Waley's work in the field of Japanese and Chinese studies is too extensive and well known to need comment here. He began about the time of the first World War and between then and 1964 he produced some forty books as well as over seventy-five articles. However, one comes upon other writings of his on very diverse sub- jects in the periodicals of the time. Articles on history, art, anthro- pology, the ballet and skiing, even a translation from the Apocalypse, and mention of his version of Hroswitha's Callimachus, which was performed at the Haymarket Theater in 1920. But poetry has been a lifelong interest ever since his undergraduate days. At King's Col- lege, Cambridge, where he was a year behind his friend Rupert Brooke, also a Rugbeian, Waley read Classics. Waley knew Beryl de Zoete, who died in 1962, for nearly fifty years. A pupil of Dalcroze, she wrote books on dancing in Bali, India and Ceylon, which are basic and authoritative works. Her linguistic gifts were extraordinary. -

BAI JUYI and the NEW YUEFU MOVEMENT by JORDAN

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Oregon Scholars' Bank BAI JUYI AND THE NEW YUEFU MOVEMENT by JORDAN ALEXANDER GWYTHER A THESIS Presented to the Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts June 2013 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Jordan Alexander Gwyther Title: Bai Juyi and the New Yuefu Movement This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures by: Yugen Wang Chairperson Maram Epstein Member Allison Groppe Member and Kimberly Andrews Espy Vice President for Research and Innovation; Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2013 ii © 2013 Jordan Alexander Gwyther iii THESIS ABSTRACT Jordan Alexander Gwyther Master of Arts Department of East Asian Languages and Literatures June 2013 Title: Bai Juyi and the New Yuefu Movement Centering my focus on a detailed translation of the poetry of Bai Juyi's New Yuefu, I will reconstruct the poet’s world on the foundation of political allegory found within his verse. Bai Juyi once said that there are four elements that compose poetry as a whole: Likened to a blossoming fruit tree, the root of poetry is in its emotions, its branches in its wording, its flowers in its rhyme and voice, and lastly its final culmination in the fruits of its meaning. -

Genji Monogatari Over a Millennium1

(Para)Translations of Genji Monogatari over a millennium1 Gisele Tyba Mayrink Orgado e Daniel Serravalle de Sá* Introduction Written between the end of the tenth century and the beginning of the eleventh century, during the Heian period (794-1185), Genji Monogatari is one of the most celebrated literary texts of Japanese culture. Its authorship is attributed to Murasaki Shikibu. This millennial work is regarded as the first literary novel written by a woman in the world. Its importance goes well beyond Japan, taking its place in the so-called “western” literary milieu, especially after its wide dissemination in English and later in other European languages. The complexity of its style, with dialogues written in verse form and the colloquial use of terminologies and expressions of the time make the text challenging to contemporary readers. Translations into modern Japanese, making this ancient text comprehensible to a contemporary readership, were crucial to updates of the work. Likewise, translations into other languages have helped overcome 10.17771/PUCRio.TradRev.48209 linguistic-cultural barriers for readers who do not speak Japanese. It will be argued here that the recent popularization of The Tale of Genji stems from this process of translating and from the paratextual elements about the translation procedures that usually accompany its translations. If on one hand, translations guarantee the survival of the text, on the other hand, they also modify it. 1 Este artigo resulta de pesquisa realizada para o Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso de Bacharelado em Letras Inglês (2018), na Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina. Parte da referida pesquisa foi publicada no idioma português no periódico Ilha do Desterro (2019). -

Downloaded27 from Brill.Com09/29/2021 10:35:02PM Via Free Access 78 Ji

Journal of chinese humanities � (���6) 77-97 brill.com/joch A Comparative Study of Two Major English Translations of The Journey to the West: Monkey and The Monkey and the Monk Hao Ji Abstract As two major English translations of a famous sixteenth-century Chinese novel The Journey to the West, Monkey by Arthur Waley and The Monkey and the Monk by Anthony Yu differ in many respects due to the translators’ different concerns and translation strategies. Whereas Waley’s translation omits many episodes and significantly changes textual features of the original novel, Yu’s translation is more literal and faithful to the original. Through a comparison of the different approaches in these two translations, this paper aims to delineate important differences in textual features and images of protagonists and demonstrate how such differences, especially the changing represen- tation of Tripitaka, might affect English-language readers’ understanding of religious references and themes in the story. It also seeks to help us reconsider the relationship between translations and the original text in the age of world literature through a case study of English translations of The Journey to the West. Keywords comparison – Monkey – The Monkey and the Monk – translation – Xiyou ji An immensely popular novel in China and East Asia, Xiyou ji 西遊記 (The Journey to the West), often attributed to Wu Cheng’en 吳承恩 (ca. 1500-1582), is loosely based on the pilgrimage of the historical figure Xuanzang 玄奘 * Hao Ji 郝稷 is an assistant professor of Chinese, Department of Modern Languages and Literatures, College of the Holy Cross, Worcester, MA, USA; e-mail: [email protected].