INTRODUCTION Par G.D. Rowley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LA INFLUENCIA De FRANCISCO HERNÁNDEZ En La CONSTITUCIÓN De La BOTÁNICA MATERIA MÉDICA MODERNAS

JOSÉ MARíA LÓPEZ PIÑERO JOSÉ PARDO TOMÁS LA INFLUENCIA de FRANCISCO HERNÁNDEZ (1515-1587) en la CONSTITUCIÓN de la BOTÁNICA y la MATERIA MÉDICA MODERNAS INSTITUTO DE ESTUDIOS DOCUMENTALES E HISTÓRICOS SOBRE LA CIENCIA UNIVERSITAT DE VALENCIA - C. S. 1. C. VALENCIA, 1996 La influencia de Francisco Hernández (1515·1587) en la constitución de la botánica y la materia médica modernas CUADERNOS VALENCIANOS DE HISTORIA DE LA MEDICINA y DE LA CIENCIA LI SERIE A (MONOGRAFÍAS) JOSÉ MARÍA LÓPEZ PIÑERO JOSÉ PARDO TOMÁS La influencia de Francisco Hernández (1515-1587) en la constitución de la botánica y la materia médica modernas INSTITUTO DE ESTUDIOS DOCUMENTALES E HISTÓRICOS SOBRE LA CIENCIA UNIVERSITAT DE VALENCIA - C.S.I.C. VALENCIA, 1996 IMPRESO EN ESPA~A PRINTED IN SPAIN I.S.B.N. 84-370-2690-3 DEPÓSITO LEGAL: v. 3.795 - 1996 ARTES GRÁFICAS SOLER, S. A. - LA OLlVERETA, 28 - 46018 VALENCIA Sumario Los estudios sobre Francisco Hernández y su obra ...................................... 9 El marco histórico de la influencia de Hernández: la constitución de la botánica y de la materia médica modernas ........................................ 21 Francisco Hernández y su Historia de las plantas de Nueva España .......................................................................................... 35 El conocimiento de las plantas americanas en la Europa de la transición de los siglos XVI al XVII ........................................................... 113 La edición de materiales de la Historia de las plantas de Nueva España durante la primera -

Caryophyllales 2018 Instituto De Biología, UNAM September 17-23

Caryophyllales 2018 Instituto de Biología, UNAM September 17-23 LOCAL ORGANIZERS Hilda Flores-Olvera, Salvador Arias and Helga Ochoterena, IBUNAM ORGANIZING COMMITTEE Walter G. Berendsohn and Sabine von Mering, BGBM, Berlin, Germany Patricia Hernández-Ledesma, INECOL-Unidad Pátzcuaro, México Gilberto Ocampo, Universidad Autónoma de Aguascalientes, México Ivonne Sánchez del Pino, CICY, Centro de Investigación Científica de Yucatán, Mérida, Yucatán, México SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Thomas Borsch, BGBM, Germany Fernando O. Zuloaga, Instituto de Botánica Darwinion, Argentina Victor Sánchez Cordero, IBUNAM, México Cornelia Klak, Bolus Herbarium, Department of Biological Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa Hossein Akhani, Department of Plant Sciences, School of Biology, College of Science, University of Tehran, Iran Alexander P. Sukhorukov, Moscow State University, Russia Michael J. Moore, Oberlin College, USA Compilation: Helga Ochoterena / Graphic Design: Julio C. Montero, Diana Martínez GENERAL PROGRAM . 4 MONDAY Monday’s Program . 7 Monday’s Abstracts . 9 TUESDAY Tuesday ‘s Program . 16 Tuesday’s Abstracts . 19 WEDNESDAY Wednesday’s Program . 32 Wednesday’s Abstracs . 35 POSTERS Posters’ Abstracts . 47 WORKSHOPS Workshop 1 . 61 Workshop 2 . 62 PARTICIPANTS . 63 GENERAL INFORMATION . 66 4 Caryophyllales 2018 Caryophyllales General program Monday 17 Tuesday 18 Wednesday 19 Thursday 20 Friday 21 Saturday 22 Sunday 23 Workshop 1 Workshop 2 9:00-10:00 Key note talks Walter G. Michael J. Moore, Berendsohn, Sabine Ya Yang, Diego F. Registration -

Pilosocereus Robinii) Using New Genetic Tools Tonya D

Volume 31: Number 2 > 2014 The Quarterly Journal of the Florida Native Plant Society Palmetto Fern Conservation in a Biodiversity Hotspot ● Saving the Endangered Florida Key Tree Cactus Saving the Endangered Florida Key Tree Cactus (Pilosocereus robinii) Using New Genetic Tools Tonya D. Fotinos, Dr. Joyce Maschinski & Dr. Eric von Wettberg Biological systems around the globe are being threatened by human-induced landscape changes, habitat degradation and climate change (Barnosky et al. 2011; Lindenmayer & Fischer 2006; Thomas et al. 2004; Tilman et al. 1994). Although there is a considerable threat across the globe, numerically the threat is highest in the biodiversity hotspots of the world. Of those hotspots, South Florida and the Caribbean are considered in the top five areas for conservation action because of the high level of endemism and threat (Myers et al. 2000). South Florida contains roughly 125 endemic species and is the northernmost limit of the distribution of many tropical species (Abrahamson 1984; Gann et al. 2002). The threat to these species comes predominantly from sea level rise, which could be >1 m by the end of the century (Maschinski et al. 2011). Above: Pilosocereus robinii stand in the Florida Keys. Photo: Jennifer Possley, Center for Tropical Conservation/Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden. Above: Pilosocereus robinii in bloom at the Center for Tropical Conservation. Photo: Devon Powell, Center for Tropical Conservation/Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden. 12 ● The Palmetto Volume 31:2 ● 2014 Restoration of imperiled populations is a priority for mitigating the looming species extinctions (Barnosky et al. 2011). Populating new or previously occupied areas or supple- menting a local population of existing individuals are strategies that improve the odds that a population or species will survive. -

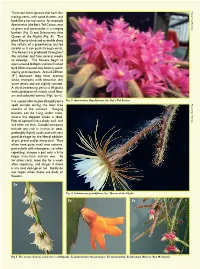

There Are Other Species That Have Thin Trailing Stems, with Spine Clusters

There are other species that have thin MottramPhoto: Roy Mottram Photo: Roy trailing stems, with spine clusters, and look like a normal cactus, for example Aporocactus (the Rat’s Tail Cactus, easy to grow and spectacular in a hanging basket) (Fig. 3) and Selenicereus (the Queen of the Night) (Fig. 4). This plant likes to climb and scramble along the rafters of a greenhouse, but be careful as it can push through vents. The flowers are produced throughout the summer and take several weeks to develop. The flowers begin to open around 8.00pm and are finished by 8.00am the next day, but it is worth staying up to see them. Around 230mm (9”) diameter, they form creamy white trumpets with brownish thin outer petals and are slightly scented. A third interesting genus is Rhipsalis with a profusion of, mainly, small flow- ers and colourful berries (Figs. 5a–c). It is a good idea to give all epiphytes a Fig. 3 Aporocactus flagelliformis, the Rat’s Tail Cactus spell outside during the frost free months of the summer. Hanging baskets can be hung under trees, where the dappled shade is ideal. Pots of epicacti like a shady wall, and will often set fruit. Suitable composts include any rich in humus or peat, preferably slightly acidic and with very good drainage by the liberal addition of grit, gravel and/or sharp sand. They often have quite small root systems, particularly schlumbergeras, so when repotting, choose a pot only a little larger than their current one. As for other cacti, leave dry for a week after repotting, and longer if there is any root damage or rot. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

SYSTEMATICS OF TRIBE TRICHOCEREEAE AND POPULATION GENETICS OF Haageocereus (CACTACEAE) By MÓNICA ARAKAKI MAKISHI A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2008 1 © 2008 Mónica Arakaki Makishi 2 To my parents, Bunzo and Cristina, and to my sisters and brother. 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I want to express my deepest appreciation to my advisors, Douglas Soltis and Pamela Soltis, for their consistent support, encouragement and generosity of time. I would also like to thank Norris Williams and Michael Miyamoto, members of my committee, for their guidance, good disposition and positive feedback. Special thanks go to Carlos Ostolaza and Fátima Cáceres, for sharing their knowledge on Peruvian Cactaceae, and for providing essential plant material, confirmation of identifications, and their detailed observations of cacti in the field. I am indebted to the many individuals that have directly or indirectly supported me during the fieldwork: Carlos Ostolaza, Fátima Cáceres, Asunción Cano, Blanca León, José Roque, María La Torre, Richard Aguilar, Nestor Cieza, Olivier Klopfenstein, Martha Vargas, Natalia Calderón, Freddy Peláez, Yammil Ramírez, Eric Rodríguez, Percy Sandoval, and Kenneth Young (Peru); Stephan Beck, Noemí Quispe, Lorena Rey, Rosa Meneses, Alejandro Apaza, Esther Valenzuela, Mónica Zeballos, Freddy Centeno, Alfredo Fuentes, and Ramiro Lopez (Bolivia); María E. Ramírez, Mélica Muñoz, and Raquel Pinto (Chile). I thank the curators and staff of the herbaria B, F, FLAS, LPB, MO, USM, U, TEX, UNSA and ZSS, who kindly loaned specimens or made information available through electronic means. Thanks to Carlos Ostolaza for providing seeds of Haageocereus tenuis, to Graham Charles for seeds of Blossfeldia sucrensis and Acanthocalycium spiniflorum, to Donald Henne for specimens of Haageocereus lanugispinus; and to Bernard Hauser and Kent Vliet for aid with microscopy. -

The Wonderful World of Cacti. July 7, 2020

OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY EXTENSION Succulents part 1: The wonderful world of cacti. July 7, 2020 Betzy Rivera. Master Gardener Volunteer OSU Extension – Franklin County OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY EXTENSION Succulent plants Are plants with parts that are thickened and fleshy, capacity that helps to retain water in arid climates. Over 25 families have species of succulents. The most representative families are: Crassulaceae, Agavaceae, Aizoaceae, Euphorbiacea and Cactaceae. 2 OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY EXTENSION The Cactaceae family is endemic to America and the distribution extends throughout the continent from Canada to Argentina, in addition to the Galapagos Islands and Antilles Most important centers of diversification (Bravo-Hollis & Sánchez-Mejorada, 1978; Hernández & Godínez, 1994; Arias-Montes, 1993; Anderson, 2001; Guzmán et al., 2003; Ortega- Baes & Godínez-Alvarez, 2006 3 OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY EXTENSION There is an exception — one of the 1,800 species occurs naturally in Africa, Sri Lanka, and Madagascar Rhipsalis baccifera 4 OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY EXTENSION The Cactaceae family includes between ~ 1,800 and 2,000 species whose life forms include climbing, epiphytic, shrubby, upright, creeping or decumbent plants, globose, cylindrical or columnar in shape (Bravo-Hollis & Sánchez-Mejorada, 1978; Hernández & Godínez, 1994; Guzmán et al., 2003). 5 OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY EXTENSION Cacti are found in a wide variety of environments, however the greatest diversity of forms is found in arid and semi-arid areas, where they play an important role in maintaining the stability of ecosystems (Bravo-Hollis & Sánchez-Mejorada, 1978; Hernández & Godínez, 1994; Guzmán et al., 2003). 6 OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY EXTENSION The Cactaceae family are dicotyledonous plants 2 cotyledons Astrophytum myriostigma (common names: Bishop´s cap cactus, bishop’s hat or miter cactus) 7 OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY EXTENSION General Anatomy of a Cactus Cactus spines are produced from specialized structures called areoles, a kind of highly reduced branch. -

Espostoa Br.& R

2021/09/25 08:03 1/10 Espostoa Br.& R. Espostoa Br.& R. Cet article est basé sur l'original écrit par Graham Charles et publié dans le British Cactus and Succulent Journal 17(2): 69-79 (1999). Vous en trouverez une traduction sur le Cactus Francophone : Espostoa Br.& R. Il est ici modifié et corrigé à la lumière de nouvelles découvertes. Notez que dans l'article original, la fig 1. à la page 68 a été incorrectement légendée. On doit lire “Espostoa melanostele dans le Canyon Tinajas, près de Lima GC157.04” Although cerei are not the most popular cacti for growers restricted by cultivation in glasshouses, almost all collections have at least one representative of this beautiful genus. Most species are easy to cultivate and the hairy stems of many species make them an attractive addition to any collection, even in a small glasshouse. In pots, they are slower growing than many cerei, a factor which also makes them good show plants, frequently seen winning the Cereus class. For exhibitors, those species with stems covered with white hair catch the judge's eye. The hair can also hide minor blemishes on the stem which would more likely get spotted and count against other less covered species! In keeping with the fashionable trend towards the broader concept of genera, Espostoa has been expanded in recent years to include species previously included in the separate genera Pseudoespostoa Backbg., Thrixanthocereus Backbg. and Vatricania Backbg. Recent molecular studies have shown that Vatricania is not an Espostoa and so it will be excluded from this revised article. -

Cactus Explorers Journal

Bradleya 34/2016 pages 100–124 What is a cephalium? Root Gorelick Department of Biology and School of Mathematics & Statistics and Institute of Interdisciplinary Studies, Carleton University, 1125 Raven Road, Ottawa, Ontario K1S 5B6 Canada (e-mail: [email protected]) Photographs by the author unless otherwise stated. Summary : There are problems with previous at - gibt meist einen abgrenzbaren Übergang vom tempts to define ‘cephalium’, such as via produc - photosynthetisch aktiven Gewebe zum nicht pho - tion of more hairs and spines, confluence of tosynthetisch aktiven und blütentragenden areoles, or periderm development at or under - Cephalium, die beide vom gleichen Triebspitzen - neath each areole after flowering. I propose using meristem abstammen. Cephalien haben eine an - the term ‘cephalium’ only for a combination of dere Phyllotaxis als die vegetativen these criteria, i.e. flowering parts of cacti that Sprossabschnitte und sitzen der vorhandenen have confluent hairy or spiny areoles exterior to a vegetativen Phyllotaxis auf. Wenn blühende Ab - thick periderm, where these hairs, spines, and schnitte nur einen Teil der oben genannten Merk - periderms arise almost immediately below the male aufweisen, schlage ich vor, diese Strukturen shoot apical meristem, and with more hairs and als „Pseudocephalien“ zu bezeichnen. spines on reproductive parts than on photosyn - thetic parts of the shoot. Periderm development Introduction and confluent areoles preclude photosynthesis of Most cacti (Cactaceae) are peculiar plants, cephalia, which therefore lack or mostly lack even for angiosperms, with highly succulent stomata. There is almost always a discrete tran - stems, numerous highly lignified leaves aka sition from photosynthetic vegetative tissues to a spines, lack of functional photosynthetic leaves, non-photosynthetic flower-bearing cephalium, CAM photosynthesis, huge sunken shoot apical both of which arise from the same shoot apical meristems, and fantastic stem architectures meristem. -

Bradleya 31/2013 Pages 142-149

Bradleya 31/2013 pages 142-149 Coleocephalocereus purpureus has a cephalium; Micrantho - cereus streckeri has a pseudocephalium (Cereeae, Cactoideae, Cactaceae) Root Gorelick Department of Biology, School of Mathematics & Statistics, and Institute of Interdisciplinary Studies Carleton University, 1125 Colonel By Drive, Ottawa, Ontario K1S 5B6 Canada. (email: [email protected]). Photographs by the author Summary : The putatively closely related cactus Introduction genera of Coleocephalocereus , Micranthocereus , Cactaceae (cacti) in the tribe Cactoideae have Cereus , Monvillea , and Stetsonia have a wide a wide range of reproductive anatomies ranging range in specialization of reproductive portions of from cephalia to pseudocephalia to forms where the shoot, from cephalium to pseudocephalium to reproductive and vegetative structures are indis - no specialization. After briefly summarizing the tinguishable (Buxbaum, 1964, 1975; Mauseth, shifting uses of the terms ‘cephalium’ and ‘pseudo - 2006). cephalium’, I provide gross morphological evi - For instance, Melocactus Link & Otto, Disco - dence that Coleocephalocereus purpureus has a cactus Pfeiffer, and Espostoa Britton & Rose have true cephalium that is formed of a continuous true cephalia in which the flowering parts are not swath of bristles and hairs, with its underlying photosynthetic because every epidermal cell con - thick cortex of parenchyma replaced by a narrow tains a modified leaf that is a hair, bristle, or layer of cork. By contrast, Micranthocereus streck - spine, with no stomata amongst the epidermal eri has a pseudocephalium composed of nothing cells (Mauseth, 2006). Furthermore, there are more than larger hairier areoles in which the un - changes to the internal anatomy of cephalia, derlying epidermis is still photosynthetic and the where the underlying cortex is not a wide swath of underlying cortex is still a thick layer of highly succulent parenchyma, but instead a thin parenchyma without any noticeable cork. -

Some Major Families and Genera of Succulent Plants

SOME MAJOR FAMILIES AND GENERA OF SUCCULENT PLANTS Including Natural Distribution, Growth Form, and Popularity as Container Plants Daniel L. Mahr There are 50-60 plant families that contain at least one species of succulent plant. By far the largest families are the Cactaceae (cactus family) and Aizoaceae (also known as the Mesembryanthemaceae, the ice plant family), each of which contains about 2000 species; together they total about 40% of all succulent plants. In addition to these two families there are 6-8 more that are commonly grown by home gardeners and succulent plant enthusiasts. The following list is in alphabetic order. The most popular genera for container culture are indicated by bold type. Taxonomic groupings are changed occasionally as new research information becomes available. But old names that have been in common usage are not easily cast aside. Significant name changes noted in parentheses ( ) are listed at the end of the table. Family Major Genera Natural Distribution Growth Form Agavaceae (1) Agave, Yucca New World; mostly Stemmed and stemless Century plant and U.S., Mexico, and rosette-forming leaf Spanish dagger Caribbean. succulents. Some family yuccas to tree size. Many are too big for container culture, but there are some nice small and miniature agaves. Aizoaceae (2) Argyroderma, Cheiridopsis, Mostly South Africa Highly succulent leaves. Iceplant, split-rock, Conophytum, Dactylopis, Many of these stay very mesemb family Faucaria, Fenestraria, small, with clumps up to Frithia, Glottiphyllum, a few inches. Lapidaria, Lithops, Nananthus, Pleisopilos, Titanopsis, others Delosperma; several other Africa Shrubs or ground- shrubby genera covers. Some marginally hardy. Mestoklema, Mostly South Africa Leaf, stem, and root Trichodiadema, succulents. -

Cactology II

Edited & published by Alessandro Guiggi Viale Lombardia 59, 21053 Castellanza (VA), Italy International Cactaceae Research Center (ICRC) [email protected] The texts have been written by Alessandro Guiggi Roy Mottram revised the English text The texts in Spanish have been translated by M. Patricia Palacios R. The texts in French have been translated by Gérard Delanoy Illustrations by the author & individual contributors All right reserved No parts of this issue may be reproduced in any form, without permission from the Publisher © Copyright ICRC ISSN 1971-3010 Cover illustration Adult plant of Melocactus intortus subsp. broadwayi with its cephalium from Micoud, Saint Lucia, Lesser Antilles. Photo by J. Senior. Back cover illustration Crested plant of Pilosocereus lanuginosus subsp. colombianus cult. hort. Jardin Exotique of Monaco. Photo by A. Guiggi. Nomenclatural novelties proposed in this issue Melocactus caesius subsp. lobelii (Suringar) Guiggi comb. nov. Melocactus macracanthos subsp. stramineus (Suringar) Guiggi comb. et stat nov. Melocactus mazelianus subsp. andinus Guiggi comb. et stat. nov. Melocactus mazelianus subsp. schatzlii (Till et R. Gruber) Guiggi comb. et stat. nov. Melocactus mazelianus subsp. schatzlii forma guanensis (Xhonneux et Fernandez- Alonso) Guiggi comb. et stat. nov. Pilosocereus lanuginosus subsp. colombianus (Rose) Guiggi comb. et stat. nov. Pilosocereus lanuginosus subsp. moritzianus (Otto ex Pfeiffer) Guiggi comb. et stat. nov. Pilosocereus lanuginosus subsp. tillianus (Gruber et Schatzl) Guiggi comb. et stat. nov. Praepilosocereus Guiggi gen. nov. Praepilosocereus mortensenii (Croizat) Guiggi comb. nov. Subpilocereus fricii (Backeberg) Guiggi comb. nov. Subpilocereus fricii subsp. horrispinus (Backeberg) Guiggi comb. et stat. nov. Corrigendum Cactology I Pag. 23: The geographical distribution of Consolea spinosissima subsp. -

Cacti, Biology and Uses

CACTI CACTI BIOLOGY AND USES Edited by Park S. Nobel UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley Los Angeles London University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 2002 by the Regents of the University of California Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cacti: biology and uses / Park S. Nobel, editor. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ). ISBN 0-520-23157-0 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Cactus. 2. Cactus—Utilization. I. Nobel, Park S. qk495.c11 c185 2002 583'.56—dc21 2001005014 Manufactured in the United States of America 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 01 10 987654 321 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48–1992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper). CONTENTS List of Contributors . vii Preface . ix 1. Evolution and Systematics Robert S. Wallace and Arthur C. Gibson . 1 2. Shoot Anatomy and Morphology Teresa Terrazas Salgado and James D. Mauseth . 23 3. Root Structure and Function Joseph G. Dubrovsky and Gretchen B. North . 41 4. Environmental Biology Park S. Nobel and Edward G. Bobich . 57 5. Reproductive Biology Eulogio Pimienta-Barrios and Rafael F. del Castillo . 75 6. Population and Community Ecology Alfonso Valiente-Banuet and Héctor Godínez-Alvarez . 91 7. Consumption of Platyopuntias by Wild Vertebrates Eric Mellink and Mónica E. Riojas-López . 109 8. Biodiversity and Conservation Thomas H. Boyle and Edward F. Anderson . 125 9. Mesoamerican Domestication and Diffusion Alejandro Casas and Giuseppe Barbera . 143 10. Cactus Pear Fruit Production Paolo Inglese, Filadelfio Basile, and Mario Schirra .