09 Becomes City 151-162

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LEICESTER - Loughborough - EAST MIDLANDS AIRPORT - DERBY

LEICESTER - Loughborough - EAST MIDLANDS AIRPORT - DERBY Mondays to Fridays pm am am am am am am am am am am am am am am am am am am pm pm pm pm pm pm LEICESTER Gravel Street Stop Z1 11.55 12.55 1.55 2.55 3.55 - 4.55 - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - LEICESTER St Margarets Bus Stn - - - - - - - - - - 5.55 - 6.25 6.45 7.05 7.25 7.45 8.05 8.30 50 10 30 4.10 4.30 4.50 5.10 5.30 5.50 LOUGHBOROUGH High Street arr 12.20 1.20 2.20 3.20 4.20 - 5.20 - - - 6.17 - 6.53 7.13 7.33 7.58 8.18 8.38 8.58 18 38 58 4.38 4.58 5.18 5.43 6.03 6.18 LOUGHBOROUGH High Street dep 12.20 1.20 2.20 3.20 4.20 4.50 5.20 5.40 5.55 6.10 6.19 6.39 6.54 7.14 7.34 7.59 8.19 8.39 8.59 19 39 59 4.39 4.59 5.19 5.44 6.04 6.19 Hathern opp Anchor Inn 12.32 1.32 2.32 3.32 4.32 5.02 5.32 5.52 6.07 6.22 6.28 6.48 7.03 7.23 7.43 8.08 8.28 8.48 9.08 then 28 48 08 4.48 5.08 5.33 5.58 6.18 6.28 Long Whatton Piper Drive l l l l l l l l l l 6.32 l l 7.27 l l 8.32 l l at 32 l l l l 5.37 l l 6.32 Diseworth opp Bull & Swan l l l l l l l l l l 6.38 l l 7.33 l l 8.38 l l these 38 l l l l 5.43 l l 6.38 Kegworth Square 12.38 1.38 2.38 3.38 4.38 5.08 5.38 5.58 6.13 6.28 l 6.54 7.09 l 7.49 8.14 l 8.54 9.14 mins l 54 14 4.54 5.14 l 6.04 6.24 l Pegasus Business Park 12.42 1.42 2.42 3.42 4.42 5.12 5.42 6.02 6.17 6.32 6.41 7.01 7.16 7.36 7.56 8.21 8.41 9.01 9.21 past 41 01 21 until 5.01 5.21 5.46 6.11 6.31 6.41 EAST MIDLANDS AIRPORT arr 12.45 1.45 2.45 3.45 4.45 5.15 5.45 6.05 6.20 6.35 6.44 7.04 7.19 7.39 7.59 8.24 8.44 9.04 9.24 each 44 04 24 5.04 5.24 5.49 6.14 6.34 6.44 EAST MIDLANDS AIRPORT -

Leicester Area Strategic Advice 2020

How can growth and partners’ aspirations be accommodated in the Leicester area over the coming decades? Leicester Area Strategic Advice July 2020 02 Contents 01: Foreword 03 02: Executive Summary 04 03: Continuous Modular Strategic Planning 07 04: Leicester Area Strategic Context 08 05: Delivering Additional Future Services 12 06: Leicester Area Capacity 16 07: Accommodating Future Services 22 08: Recommendations and Next Steps 27 Photo credits: Front cover - lower left: Jeff Chapman Front cover - lower right: Jamie Squibbs Leicester Area Strategic Advice July 2020 03 01 Foreword The Leicester Area Strategic Advice forms part of the The report was produced collaboratively with inputs railway industry’s Long-Term Planning Process covering from key, interested organisations and considers the the medium-term and long-term planning horizon. impact of planned major programmes such as High Investment in the railway is an aid to long-term Speed 2 (HS2), and the strategies and aspirations of sustainable growth for the Leicester area, supporting bodies such as Leicester City Council, the Department economic, social and environmental objectives. of Transport (DfT), Midlands Connect and the Train Network Rail has worked collaboratively with rail and Freight Operating Companies. industry stakeholders and partners to develop long- The recommendations from this report support term plans for a safe, reliable and efficient railway to Network Rail’s focus of putting passengers first by support economic growth across Britain. aiming to increase the number of direct services from This study has considered the impact of increased Leicester Station, supporting freight growth and demand for passenger services in the medium and improving performance and satisfaction with the rail long term, starting from a baseline of today’s railway, network. -

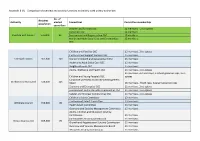

Changes in the Ethnic Diversity of the Christian Population in England

National Census 2001 and 2011 Changes in the Ethnic Diversity of the Christian Population in England between 2001 and 2011 East Midlands Region Council for Christian Unity 2014 CONTENTS Foreword from the Chair of the Council for Christian Unity Page 1 Summary and Headlines Page 2 Introduction Page 2 Christian Ethnicity - Comparison of 2001 and 2011 Census Data Page 5 In England Page 5 By region Page 8 Overall trends Page 24 Analysis of Regional data by local authority Page 27 Introduction Page 27 Tables and Figures Page 28 Annex 2 Muslim Ethnicity in England Page 52 Census 2001/2011 East Midlands CCU(14)C3 Changes in the Ethnic Diversity of the Christian Population in England between 2001 and 2011 Foreword from the Chair of the Council for Christian Unity There are great ecumenical, evangelistic, pastoral and missional challenges presented to all the Churches by the increasing diversity of Christianity in England. The comparison of Census data from 2001 and 2011about the ethnic diversity of the Christian population, which is set out in this report, is one element of the work the Council for Christian Unity is doing with a variety of partners in this area. We are very pleased to be working with the Research and Statistics Department and the Committee for Minority Ethnic Anglican Affairs at Church House, and with Churches Together in England on a number of fronts. We hope that the set of eight reports, for each of the eight regions of England, will be a helpful resource for Church Leaders, Dioceses, Districts and Synods, Intermediate Ecumenical Bodies and local churches. -

Comparison of Overview and Scrutiny Functions at Similarly Sized Unitary Authorities

Appendix B (4) – Comparison of overview and scrutiny functions at similarly sized unitary authorities No. of Resident Authority elected Committees Committee membership population councillors Children and Families OSC 12 members + 2 co-optees Corporate OSC 12 members Cheshire East Council 378,800 82 Environment and Regeneration OSC 12 members Health and Adult Social Care and Communities 15 members OSC Children and Families OSC 15 members, 2 co-optees Customer and Support Services OSC 15 members Cornwall Council 561,300 123 Economic Growth and Development OSC 15 members Health and Adult Social Care OSC 15 members Neighbourhoods OSC 15 members Adults, Wellbeing and Health OSC 21 members, 2 co-optees 21 members, 4 church reps, 3 school governor reps, 2 co- Children and Young People's OSC optees Corporate Overview and Scrutiny Management Durham County Council 523,000 126 Board 26 members, 4 faith reps, 3 parent governor reps Economy and Enterprise OSC 21 members, 2 co-optees Environment and Sustainable Communities OSC 21 members, 2 co-optees Safeter and Stronger Communities OSC 21 members, 2 co-optees Children's Select Committee 13 members Environment Select Committee 13 members Wiltshere Council 496,000 98 Health Select Committee 13 members Overview and Scrutiny Management Committee 15 members Adults, Children and Education Scrutiny Commission 11 members Communities Scrutiny Commission 11 members Bristol City Council 459,300 70 Growth and Regeneration Scrutiny Commission 11 members Overview and Scrutiny Management Board 11 members Resources -

Income, Skills and Deprivation in Leicester and Nottingham

Institute for Applied Economics and Social Value East Midlands Economic Data Repository Short Report 21-02 Income, Skills and Deprivation in Leicester and Nottingham Data for this report is available at If citing this work please use: Cartwright, E., T. Luong and Al. Orazgani (2021) ‘Income, skills and deprivation in Leicester and Nottingham’. IAESV EMEDR Data Brief 21-02. Introduction In this data brief we provide some background on economic deprivation in Leicester and Nottingham. The data in this report largely pre-dates the coronavirus pandemic and so identifies long-term economic challenges in the respective cities. The coronavirus pandemic will no doubt exasperate these challenges. In the brief we look at: • Measures of deprivation, • Employment and wages, • Skills and type of employment. Key findings • Leicester and Nottingham are two of the most deprived areas in England with high levels of income deprivation and skills deprivation. • In comparison to other cities, Leicester and Nottingham residents earn relatively low salaries and work in relatively low-skilled occupations. • In comparison to other cities, Leicester residents have relatively low levels of qualification. Nottingham is closer to the national average. Definitions We focus on Leicester and Nottingham as defined by the unitary authority boundary. We also focus on people who are resident in the two cities, rather than people who work there. Source of data. We are using data from a range of sources but primarily the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE) and the Annual Population Survey (APS), accessed on Nomis. The Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings is based on a snapshot of the workforce in April of each year. -

NHS North Lincolnshire Clinical Commissioning Group 2014-15

NHS North Lincolnshire Clinical Commissioning Group 2014-15 Annual Report Contents 1. Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….…… 1 2. Welcome from the CCG Chair and Chief Officer ………………………………………………………….….. 3 3. Member Practices Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………….. 5 4. Strategic Report 4.1 About the CCG and its community ……………………………………………………………………….….. 9 4.2 The CCG business model ………………………………………………………………………………………….. 11 4.3 The CCG strategy ……………………………………………………………………………………………………… 13 4.4 Achievements this year ……………………………………………………………………………………………. 15 4.5 Risks facing the CCG …………………………………………………………………………………………………. 18 4.6 CCG performance …………………………………………………………………………………….…………..….. 19 4.7 The wider context in which the CCG operates …………………………………………………….……. 20 4.8 The CCG’s year-end financial position ………………………………………………………………………. 21 4.9 Going concern ………………………………………………………………………………………………….…….... 22 4.10 Assurance Framework ……………………………………………………………………………………………. 22 4.11 Sustainability Report ………………………………………………………………………………………………. 27 4.12 Equality and Diversity Report …………………………………………………………………………………. 32 4.13 Key Performance indicators ……………………………………………………………………………………. 36 4.14 Accountable Officer Declaration……………………………………………………………………………… 36 5. The Members’ Report 5.1 The Governing Body ………………………………………………………………………………………………… 37 5.2 Member practices of the CCG ……………………………………………………………………………..…. 38 5.3 Audit Group …………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 41 5.4 Committee and Sub-committee membership and Declarations of interest -

Derby Nottingham Leicester # # # # # # # Cc05 : East Midlands

T070 #17 A38 EUROGAUGE-CAPABLE NORTH- A61 HIGH SPEED UK : REGIONAL MAPS SOUTH FREIGHT ROUTE 0 ASHFIELD PARKWAY 07 1 ALFRETON T04 CC05 : EAST MIDLANDS KIRKBY in MML T069 2828 ASHFIELD T05 214 © NETWORK2020 MAPPING JULY 2018 A6 FOR EXPLANATION OF SYMBOLS IN M1 T068 HSUK MAPPING SEE KEY PLAN K01 HSUK 27 A60 FOR FURTHER INFO SEE HSUK EAST MIDLANDS RAIL STRATEGY T067 NOTTINGHAM–BOTTESFORD–GRANTHAM 16 ROUTE UPGRADED & BOTTESFORD–NEWARK A38 # HUCK- BELPER A610 ROUTE RESTORED TO ACCESS ECML TO 0T066 NALL SOUTH & NORTH AND ENHANCE INTERCITY GREAT NORTHERN ROUTE 1 FLOWS THROUGH NOTTINGHAM FROM DERBY TO EREWASH EASTWOOD BIRMINGHAM- VALLEY RESTORED TO NOTTINGHAM ALLOW DIRECT ACCESS TO DIRECT HS HSUK FROM UPGRADED NOTTINGHAM ROUTE VIA XCML ROUTE VIA DERBY RESTORED T065 EXPRESS D065 26 DERBY TRANSIT TEARDROP D064 (NET) T064 NOTTINGHAM D063 ILKESTON N161 N065 N068 PRIMARY HIGH D062 N162 N064 N067 SPEED INTERCITY HUB AT DERBY HSUK & NORTH-SOUTH MIDLAND EUROGAUGE FREIGHT N066 15 ROUTE VIA TOTON YARD # D061 & EREWASH VALLEY LINE, 0 T063 A52 A38 UPGRADED/RESTORED TO N063 D001 4 TRACKS 1 25 A46 DERBY T062 D060 A52 N062 A606 NOTE ONGOING A453 NET EXTENSIONS D059 A6 MML T061 TO TOTON & XCML N061 PRIMARY HIGH SPEED CLIFTON INTERCITY HUB AT D058 NOTTINGHAM MIDLAND A50 T060 POTENTIAL FREIGHT YARD 5 D057 & TRAIN MAINTENANCE 5 24A #14 DEPOT AT TOTON 24 HSUK0 DIRECT HIGH SPEED ACCESS TO NOTTINGHAM VIA NEW DERBY AVOIDING LINE UPGRADED AS 1 EAST T059 ROUTE AVOIDING ATTEN- CORE ELEMENT OF EUROGAUGE- MML BOROUGH LEVEL CROSSINGS CAPABLE NORTH-SOUTH FREIGHT ROUTE MIDLANDS -

List of Polling Stations for Leicester City

List of Polling Stations for Leicester City Turnout Turnout City & Proposed 2 Polling Parliamentary Mayoral Election Ward & Electorate development Stations Election 2017 2019 Acting Returning Officer's Polling Polling Place Address as at 1st with potential at this Number comments District July 2019 Number of % % additional location of Voters turnout turnout electorate Voters Abbey - 3 member Ward Propose existing Polling District & ABA The Tudor Centre, Holderness Road, LE4 2JU 1,842 750 49.67 328 19.43 Polling Place remains unchanged Propose existing Polling District & ABB The Corner Club, Border Drive, LE4 2JD 1,052 422 49.88 168 17.43 Polling Place remains unchanged Propose existing Polling District & ABC Stocking Farm Community Centre, Entrances From Packwood Road And Marwood Road, LE4 2ED 2,342 880 50.55 419 20.37 Polling Place remains unchanged Propose existing Polling District & ABD Community of Christ, 330 Abbey Lane, LE4 2AB 1,817 762 52.01 350 21.41 Polling Place remains unchanged Propose existing Polling District & ABE St. Patrick`s Parish Centre, Beaumont Leys Lane, LE4 2BD 2 stations 3,647 1,751 65.68 869 28.98 Polling Place remains unchanged Whilst the Polling Station is adequate, ABF All Saints Church, Highcross Street, LE1 4PH 846 302 55.41 122 15.76 we would welcome suggestions for alternative suitable premises. Propose existing Polling District & ABG Little Grasshoppers Nursery, Avebury Avenue, LE4 0FQ 2,411 1,139 66.61 555 27.01 Polling Place remains unchanged Totals 13,957 6,006 57.29 2,811 23.09 Aylestone - 2 member Ward AYA The Cricketers Public House, 1 Grace Road, LE2 8AD 2,221 987 54.86 438 22.07 The use of the Cricketers Public House is not ideal. -

23-25 Whitley Street Reading, Berkshire RG2 0EG Flats 26, 27

Flats 26, 27 & 39 Minster Court LOT 2 Lower Brown Street 81 Leicester, Leicestershire LE1 5TH By Order of a Housing Association Three flats located in an attractive block let on Assured Shorthold Tenancies, well located for the centre of Leicester and De Montfort University. Investment let at £17,820 per annum . Tenure Leicester Leasehold. 125 year lease from 29th Description September 2002. • Three flats located in an attractive Ground rent £100 per annum. apartment block • Two allocated parking spaces Location • Situated by the junction with York Road Accommodation and Tenancies • A variety of shops, cafés, bars and A schedule of Accommodation and restaurants can be found close by in Tenancies is set out bel ow. the centre of Leicester • Castle Park and Nelson Mandela Park Total Current Rent £17,820 per annum are both within easy reach • Highly convenient for De Montfort University and Leicester Royal Infirmary Unit Accommodation Tenancy Rent (p.c. m.) Flat 26 One Bedroom Flat Assured Shorthold Tenancy £450 Plan not to scale Flat 27 Two Bedroom Flat Assured Shorthold Tenancy £560 Crown Copyright reserved. Flat 39 One Bedroom Flat Assured Shorthold Tenancy £475 This plan is based upon the Ordnance Survey Map with the sanction of the Controller of H M Stationery Office. LOT 23-25 Whitley Street 82 Reading, Berkshire RG2 0EG A mid terrace building arranged as a ground floor shop unit (let at £17,000 per annum) and a ten bedroom fully licensed vacant HMO above which has been recently refurbished. Well located in the centre of Reading, close to local shops and restaurants. -

Identifying Richard III – an Interview with Dr Turi King

The Post Hole Special Feature Identifying Richard III – an interview with Dr Turi King Emily Taylor1 1Department of Archaeology, University of York, The King’s Manor, York, YO1 7EP Email: [email protected] In light of the recent discovery of Richard III, Dr Turi King, lecturer in genetics and archaeology at the University of Leicester, talks about her involvement in the research project that found England’s final Plantagenet king in this exclusive interview with The Post Hole. You were an important part in the exciting search for Richard III. When did you become involved with the project? Richard Buckley contacted me about the idea of my involvement in 2011, but it wasn’t until August 2012 that the project went ahead. The University of Leicester worked in collaboration with the Richard III Society and Leicester City Council and the search didn’t begin until 2012 due to issues with getting funding sorted and carrying out the desk-based survey. In 1986, David Baldwin wrote an article called 'King Richard's Grave in Leicester' giving the potential location of Richard’s grave. Then the historian John Ashdown-Hill wrote a book in 2011, The Last Days of Richard III, which again spoke about the likely location of the grave and also included a section on the possibility of identifying Richard through DNA analysis. John had traced a female line relative of Richard III, Joy Ibsen, who could act as a comparator if any putative remains of Richard III were found. This, among other things, inspired Philippa Langley to contact the University of Leicester Archaeological Services about the possibility of carrying out an archaeological project. -

Interpreting Differential Health Outcomes Among Minority Ethnic Groups in Wave 1 and 2

Interpreting differential health outcomes among minority ethnic groups in wave 1 and 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. It is clear from ONS quantitative studies that all minority ethnic groups in the UK have been at higher risk of mortality throughout the Covid-19 pandemic (high confidence). Data on wave 2 (1st September 2020 to 31st January 2021) shows a particular intensity in this pattern of differential mortality among Bangladeshi and Pakistani groups (high confidence). 2. This paper draws on qualitative and sociological evidence to understand trends highlighted by the ONS data and suggests that the mortality rates in Bangladeshi and Pakistani groups are due to the amplifying interaction of I) health inequities, II) disadvantages associated with occupation and household circumstances, III) barriers to accessing health care, and IV) potential influence of policy and practice on Covid-19 health- seeking behaviour (high confidence). I) Health inequities 3. Pakistani and Bangladeshi groups suffer severe, debilitating underlying conditions at a younger age and more often than other minority ethnic groups due to health inequalities. They are more likely to have two or more health conditions that interact to produce greater risk of death from Covid-19 (high confidence). 4. Long-standing health inequities across the life course explain, in part, the persistently high levels of mortality among these groups in wave 2 (high confidence). II) Disadvantages associated with occupation and household circumstances 5. Occupation: Pakistani and Bangladeshi communities are more likely to be involved in: work that carries risks of exposure (e.g. retail, hospitality, taxi driving); precarious work where it is more difficult to negotiate safe working conditions or absence for sickness; and small-scale self-employment with a restricted safety net and high risk of business collapse (high confidence). -

Be Part of Nottingham's Most Vibrant Leisure Destination

BE PART OF NOTTINGHAM'S MOST VIBRANT LEISURE DESTINATION NOTTINGHAM'S NUMBER ONE LEISURE AND ENTERTAINMENT DESTINATION, BASED IN THE HEART OF NOTTINGHAM CITY CENTRE 200,000 SQ FT OF LEISURE SPACE – 02 – THE CORNERHOUSE l NOTTINGHAM THE CORNERHOUSE l NOTTINGHAM NOTTINGHAM IS THE LARGEST URBAN CONURBATION WITHIN THE EAST MIDLANDS AREA York LOCATIONM6 LEEDS BRADFORD KINGSTON UPON HULL Rochdale Wakefield Southport M62 Huddersfield Scunthorpe Bolton M1 M180 Grimsby Barnsley Doncaster Wigan Oldham MANCHESTER Rotherham A15 LIVERPOOL Stockport SHEFFIELD A1 M56 M1 Lincoln A158 M6 Chester A1 A46 A15 Crewe STOKE -ON-TRENT NOTTINGHAM A17 DERBY M6 A46 M1 Stafford A1 Shrewsbury Norwich Tamworth M42 Telford Great Yarmouth M54 LEICESTER WOLVERHAMPTON Peterborough M69 Nuneaton Lowestoft Corby BIRMINGHAM A1 (M) M6 COVENTRY M45 n Nottingham is an attractive historic city and is the n The Nottingham Express Transit tram network, which largest urban conurbation within the east Midlands area. opened following an expansion in August 2015, provides THE NET TRAM NETWORK The closest large city is Leicester which is located services to approximately 23 million passengers a year. CARRIES OVER 23 MILLION approximately 30 miles to the south. n Nottingham has very good road and transport n The city has an exceptional public transport network, communications with the M1 motorway only PASSENGERS A YEAR boasting the largest bus network in England. 5 miles to the west of the city centre and directly n Nottingham Railway Station provides connections to accessed via the