The Isle of Wight in the English Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Road Name Town 123456

List of roads treated APPENDIX 1 P1 Priority Snow Clearance Route P1 and P2 Precautionary Salting Routes SALT OUTE P1 OUTE SALT P2 OUTE SALT ROAD CLASS ROUTE NUMBER SECTION ROAD NAME TOWN 123456 ADELAIDE GROVE EAST COWES C R 1 All 1 - - - - - AFTON ROAD FRESHWATER A R 5 Newport Rd to Freshwater Bay - - - - 5 - AFTON ROAD FRESHWATER A R 6 School Green Rd to Newport Rd - - - - - 6 ALBERT STREET VENTNOR A R 3 All - - 3 - - - ALEXANDRA ROAD RYDE B R 1 St Johns Hill to Gt Preston Rd 1 - - - - - ALEXANDRA ROAD RYDE B R 1 St Johns Hill to Easthill Rd 1 - - - - - ALPINE ROAD VENTNOR A R 3 - - 3 - - - ALUM BAY NEW ROAD TOTLAND B R 6 Church Hill to Cliff Road - - - - - 6 ALVERSTONE ROAD NEWCHURCH C R 3 Newport Rd to Forest Rd / All - - 3 - - - ALVERSTONE SHUTE NEWCHURCH C R 3 All - - 3 - - - APPLEFORD ROAD GODSHILL C R 4 All - - - 4 - - APPLEY ROAD RYDE B R 1 Easthill Rd to Marlborough Rd 1 - - - - - APPLEY ROAD RYDE B R 2 Marlborough Rd to Puckpool Hill - 2 - - - - ARGYLL STREET RYDE R 1 All 1 - - - - - ARRETON ROAD ARRETON A R 3 All - - 3 - - - ARRETON STREET ARRETON A R 3 All - - 3 - - - ARTHURS HILL SHANKLIN A R 3 All - - 3 - - - ASHEY ROAD RYDE C R 1 Upton Rd to Smallbrook Lane 1 - - - - - ASHEY ROAD RYDE C R 2 Smallbrook Lane to Brading Down - 2 - - - - ATHERLEY ROAD SHANKLIN C R 3 All - - 3 - - - AVENUE ROAD FRESHWATER A R 6 All - - - - - 6 AVENUE ROAD SANDOWN A B R 3 All - - 3 - - - BARING ROAD COWES R 6 - - - - - 6 BARRACK SHUTE NITON A R 4 All - - - 4 - - BEACHFIELD ROAD SANDOWN B R 3 All - - 3 - - - BEAPER SHUTE BRADING A R 2 All - 2 -

Wind Farm Search Areas

Isle of Wight Windfarm Site Search Assessment September 2008 Isle of Wight Wind farm Site Assessment Project Title: Wind Farm Site Assessment Report Title: Isle of Wight Windfarm Site Search Assessment Project No: 49316016 Report Ref: Status: Draft for client comment Client Contact Name: Wendy Perera Client Company Name: Isle of Wight Council Issued By: URS Corporation Ltd St George’s House 5 St George’s Road London SW19 4DR Document Production / Approval Record Issue No: Name Signature Date Position Prepared Ben Stephenson and 29 August GIS Manager by Maria Ayerra 2008 Project Manager Checked Maria Ayerra 29 August Project Manager by 2008 Approved Andrew Bradbury 29 August Associate Director by 2008 Document Revision Record Issue No Date Details of Revisions 1 01 September 2008 Draft for client comment 2 07 September 2008 Client comments for URS 3 11 September 2008 Client comments review 4 19 September 2008 Client responses for URS 5 23 September 2008 Report Edition Isle of Wight Windfarm Site Assessment i LIMITATION URS Corporation Limited (URS) has prepared this Report for the sole use of in accordance with the Agreement under which our services were performed. No other warranty, expressed or implied, is made as to the professional advice included in this Report or any other services provided by us. This Report may not be relied upon by any other party without the prior and express written agreement of URS. Unless otherwise stated in this Report, the assessments made assume that the sites and facilities will continue to be used for their current purpose without significant change. -

Historic Environment Action Plan the Undercliff

Directorate of Community Services Director Sarah Mitchell Historic Environment Action Plan The Undercliff Isle of Wight County Archaeology and Historic Environment Service October 2008 01983 823810 archaeology @iow.gov.uk Iwight.com HEAP for the Undercliff. INTRODUCTION This HEAP Area has been defined on the basis of geology, topography, land use and settlement patterns which differentiate it from other HEAP areas. This document identifies essential characteristics of the Undercliff as its geomorphology and rugged landslip areas, its archaeological potential, its 19 th century cottages ornés /marine villas and their grounds, and the Victorian seaside resort character of Ventnor. The Area has a highly distinctive character with an inner cliff towering above a landscape (now partly wooded) demarcated by stone boundary walls. The most significant features of this historic landscape, the most important forces for change and key management issues are considered. Actions particularly relevant to this Area are identified from those listed in the Isle of Wight HEAP Aims, Objectives and Actions. ANALYSIS AND ASSESSMENT Location, Geology and Topography • The Undercliff is identified as a discrete Landscape Character Type in the Isle of Wight AONB Management Plan (2004, 132). • The Area lies to the south of the South Wight Downland , from which it is separated by vertical cliffs forming a geological succession from Ferrugunious Sands through Sandrock, Carstone, Gault Clay, Upper Greensand, Chert Beds and Lower Chalk (Hutchinson 1987, Fig. 6). o The zone between the inner cliff and coastal cliff is a landslip area o This landslip is caused by groundwater lubrication of slip planes within the Gault Clays and Sandrock Beds. -

SOUTH WEST Newquay Beach Newquay, Facing the Atlantic Ocean

SOUTH WEST Newquay Beach Newquay, facing the Atlantic Ocean on the North Cornwall Coast, is the largest resort in Cornwall. There are many different beaches to choose from including: Towan Beach, Fistral Beach, Lusty Glaze, Holywell Bay and Crantock. Reachable by a stiff walk from the village of West Pentire, is Porth Joke, also known as Polly Joke, a delightful suntrap of a beach, surrounded by low cliffs, some with sea caves, unspoilt and popular with families. A stream runs down the valley, and open fields and low dunes lead right onto the head of the beach. The beach is popular with body boarders. Often cattle from the nearby Kelseys, an ancient area of springy turfed grassland, rich in wildflowers, can be found drinking from the stream. Beyond the headland is Holywell Bay arguably one of the most beautiful beaches in Cornwall, backed by sand dunes framed by the Gull Rocks off shore. Reachable by a 15 minute walk from the Car Park. It is a nice walk west along the Coast to Penhale Point, with superb views across Perran Bay, with Perranporth in the middle distance. Nearest Travelodge: Stay at the St Austell Travelodge, Pentewan Road, St Austell, Cornwall, PL25 5BU from as little as £29 per night, best deals can be found online at www.travelodge.co.uk Clifton Suspension Bridge- Bristol The Clifton Suspension Bridge, is the symbol of the city of Bristol. Stroll across for stunning views of the Avon gorge and elegant Clifton. For almost 150 years this Grade I listed structure has attracted visitors from all over the world. -

Steam Railway

STEAM RAILWAY VENTURES IN SANDOWN 1864 - 1879 - 1932 - 1936 - 1946 - 1948 - 1950 When a Beyer Peacock 2-4-0 locomotive entered the newly built Sandown Railway Station on August 23rd 1864, it was the first steam passenger train to grace the town. It is more than probable that many local people had never seen the likes of it before, even more unlikely was that many of them would ride on one, as the cost of railway travel was prohibitive for the working class at the time. The Isle of Wight Railway ran from Ryde St. Johns Road to Shanklin until 1866 when the extension to Ventnor was completed. The London & South Western Railway in conjunction with the London Brighton & South Coast Railway, joined forces to build the Railway Pier at Ryde and complete the line from Ryde St. Johns to the Pier Head in 1880. The line to Ventnor was truncated at Shanklin and closed to passengers in April 1966, leaving the 8½ miles that remains today. On August 23rd 2008 the initial section will have served the Island for 144 years, and long may it continue. The Isle of Wight Railway, in isolation on commencement from the Cowes and Newport Railway (completed in 1862) were finally connected by a branch line from Sandown to Newport in 1879. Curiously named, the Isle of Wight Newport Junction Railway, it ran via Alverstone, Newchurch, Merstone, Horringford, Blackwater and Shide. Never a financial success, it served the patrons of the line well, especially during the war years, taking hundreds of workers to the factories at East and West Cowes. -

Historic Environment Action Plan South-West Wight Coastal Zone

Island Heritage Service Historic Environment Action Plan South-West Wight Coastal Zone Isle of Wight County Archaeology and Historic Environment Service October 2008 01983 823810 archaeology @iow.gov.uk Iwight.com HEAP for South-West Wight Coastal Zone INTRODUCTION This HEAP Area has been defined on the basis of geology, topography land use and settlement patterns which differentiate it from other HEAP areas. Essential characteristics of the South-West Wight Coastal Zone include the long coastline and cliffs containing fossils and archaeological material, the pattern of historic lanes, tracks and boundaries, field patterns showing evidence of open-field enclosure, valley-floor land, historic villages, hamlets and dispersed farmsteads, and vernacular architecture. The Military Road provides a scenic and historically significant route along the coast. The settlements of Mottistone, Hulverstone, Brighstone and Shorwell straddle the boundary between this Area and the West Wight Downland Edge & Sandstone Ridge. Historically these settlements exploited both Areas. For the sake of convenience these settlements are described in the HEAP Area document for the West Wight Downland Edge & Sandstone Ridge even where they fall partially within this Area. However, they are also referred to in this HEAP document where appropriate. This document considers the most significant features of the historic landscape, the most important forces for change, and the key management issues. Actions particularly relevant to this Area are identified from those listed in the Isle of Wight HEAP Aims, Objectives and Actions. ANALYSIS AND ASSESSMENT Location, Geology and Topography • Occupies strip of land between West Wight Downland Edge & Sandstone Ridge and coast. • Coastline within this Area stretches from Compton to Shepherd’s Chine and comprises soft, eroding cliffs with areas of landslip. -

Land at Borthwood Lane | Newchurch | Sandown | PO36 OHH Guide Price £48,000

Land at Borthwood Lane | Newchurch | Sandown | PO36 OHH Guide Price £48,000 An area of land which extends to approximately 5 acres and is Freehold. The land is currently Approximately 5 Acres of pasture and has easy access to the Island's extensive bridleway network. The land is partly Land hedged and fenced. The neighbouring Borthwood Copse (National Trust) is a Site of Important Currently used as Pasture Nature Conservation (S.I.N.C.) and is home to many species of wildlife including the Island's Land well-known red squirrels. Access to Bridleways Secure gated entrance Property Description From Newport take the A3056 signal to Sandown. Proceed through Arreton an at Thompson Nursery and turn left into An area of land which extends to approximately 5 acres and is Watery Lane. At the cross roads go straight ahead into Forest Freehold. The land is currently pasture and has easy access to the Island's extensive bridleway network. The land is partly hedged and Road and then left into Alverstone Road. Do not turn left into fenced. The neighbouring Borthwood Copse (National Trust) is a Site Skinners Hill; Borthwood Lane will be found on the right hand of Important Nature Conservation (S.I.N.C.) and is home to many side. Turn into the lane and the Land will be found on the right species of wildlife including the Island's well-known red squirrels. side after 300m Newchurch Newchurch is a very popular village in the south east of the Viewing arrangements Island about 8 miles from Island’s main shopping and Viewing is strictly by appointment with the Sole Agents Biles & administrative centre of Newport. -

(ALERT ) on Attitudes and Confidence in Managing Critically Ill Adult Patients

Resuscitation 65 (2005) 329–336 Impact of a one-day inter-professional course (ALERTTM) on attitudes and confidence in managing critically ill adult patientsଝ Peter Featherstone a, b, Gary B. Smith b, c, ∗, Maggie Linnell d, Simon Easton d, Vicky M. Osgood b a Portsmouth Institute of Medicine, Health & Social Care, University of Portsmouth, UK b Portsmouth Hospitals NHS Trust, UK c Institute of Health & Community Studies, University of Bournemouth, UK d Department of Psychology, University of Portsmouth, UK Received 12 October 2004; accepted 10 December 2004 Abstract Anecdotal evidence suggests that anxiety and lack of confidence in managing acutely ill patients adversely affects performance. We evaluated the impact of attending an ALERTTM course on the confidence levels and attitudes of healthcare staff in relation to the recognition and management of acutely ill patients. A questionnaire, which examined knowledge, experience, confidence and teamwork, was distributed to participants prior to commencing an ALERTTM course. One hundred and thirty-one respondents agreed to participate in a follow-up questionnaire 6 weeks after completing the course. Respondents reported significantly more knowledge (pre 5.47 ± 1.69, post 7.37 ± 1.22; p < 0.01) in recognising a critically ill patient after attending an ALERTTM course. Mean scores for respondents’ confidence in their ability to recognise a critically ill patient (pre 6.04; post 7.71; t = 11.74; p < 0.01), keep such a patient alive (pre 5.70; post 7.30; t = 10.01; p < 0.01) and remember all the life-saving measures (pre 5.60; post 7.32; t = 11.71; p < 0.01) were increased. -

Neolithic & Early Bronze Age Isle of Wight

Neolithic to Early Bronze Age Resource Assessment The Isle of Wight Ruth Waller, Isle of Wight County Archaeology and Historic Environment Service September 2006 Inheritance: The map of Mesolithic finds on the Isle of Wight shows concentrations of activity in the major river valleys as well two clusters on the north coast around the Newtown Estuary and Wooton to Quarr beaches. Although the latter is likely due to the results of a long term research project, it nevertheless shows an interaction with the river valleys and coastal areas best suited for occupation in the Mesolithic period. In the last synthesis of Neolithic evidence (Basford 1980), it was claimed that Neolithic activity appears to follow the same pattern along the three major rivers with the Western Yar activity centred in an area around the chalk gap, flint scatters along the River Medina and greensand activity along the Eastern Yar. The map of Neolithic activity today shows a much more widely dispersed pattern with clear concentrations around the river valleys, but with clusters of activity around the mouths of the four northern estuaries and along the south coast. As most of the Bronze Age remains recorded on the SMR are not securely dated, it has been difficult to divide the Early from the Late Bronze Age remains. All burial barrows and findspots have been included within this period assessment rather than the Later Bronze Age assessment. Nature of the evidence base: 235 Neolithic records on the County SMR with 202 of these being artefacts, including 77 flint or stone polished axes and four sites at which pottery has been recovered. -

The Top Cliff Walk

THE TOP CLIFF WALK It is less than two miles along the top cliff from St. Lawrence to Niton. There is only one stiff climb, one stile and, except immediately after heavy rain, very little mud. So it is a relatively easy walk, yet exhilarating at all times of the year, with a winter bonus of sunsets over the English Channel. Although the flora is not as varied as on the bottom cliff, wildlife is abundant, especially birds, with raptors frequently riding the thermals and skylarks common in summer. Officially, the walk is a section of the Isle of Wight Coastal Path. From St. Lawrence village shop, head up Spindlers Road and turn left at the junction with Seven Sisters Road. About a hundred yards along Seven Sisters Road you will see a signpost to Whitwell on you right. Follow this path, which crosses the route of the former railway then climbs quite steeply up the cliff face. The entrance to the old St. Lawrence railway tunnel is hidden in the dense vegetation below. When you emerge on the cliff-top you will see a signpost ahead of you at a grassy crossways. Turn left here, following the sign to Niton, and just keep going! As you cross this first field, with the communications mast on your right, there are fine views south across the Undercliff towards the "Sugar Loaf" beside Woody Bay. Soon you will reach the only stile on the route and for a while the view south is obscured by the cliff- top hedge, but looking north you can see across Whitwell to Newport, ten miles away. -

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 17Xh DECEMBER 1971 13871

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 17xH DECEMBER 1971 13871 Objections to the proposal must be sent in Alternative routes are available as follows: writing stating the grounds on which they are being Via Apse Heath made to the undersigned by 10th January 1972, quot- Lake ing the reference 39.04/881. Sandown Peter Boyce, Clerk of the County Council. Adgestone County Hall, Alverstone Hertford. Or Newchurch 17th December 1971. (293) Brading Down Adgestone Alverstone HAZEL GROVE AND BRAMHALL L. H. Baines, Clerk of the County Council. URBAN DISTRICT COUNCIL County Hall, The Urban District of Hazel Grove and Bramhall Newport, I.W. (Robins Lane, Bramhall) (Weight Restriction) Order 15th December 1971. ' ' (457) 1971. Notice is hereby given that the Hazel Grove and Bramhall Urban District Council propose to make ISLE OF WIGHT COUNTY COUNCIL an Order under section 1 (1), (2) and (3) of the The Isle of Wight (Forest Road, Winford) (Tem- Road Traffic Regulation Act 1967, as amended, the porary Prohibition of Through Traffic) Order No. effect of which will be to restrict to 2 tons the 1 1972. unladen weight of vehicles using Robins Lane, Bram- Notice is hereby given that the Isle of Wight County hall, from the junction with Hardy Drive to the Council acting in pursuance of its powers under junction with St. Michael's Avenue. There will be section 12 (1) of the Road Traffic Regulation Act the usual exemptions for access to premises and 1967, as amended by Part IX of the Transport Act •to enable works to be carried out in the road, etc. -

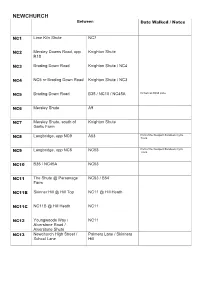

NEWCHURCH Between Date Walked / Notes

NEWCHURCH Between Date Walked / Notes NC1 Lime Kiln Shute NC7 NC2 Mersley Downs Road, opp Knighton Shute R18 NC3 Brading Down Road Knighton Shute / NC4 NC4 NC5 nr Brading Down Road Knighton Shute / NC3 NC5 Brading Down Road B35 / NC10 / NC45A Known as Blind Lane NC6 Mersley Shute A9 NC7 Mersley Shute, south of Knighton Shute Garlic Farm Langbridge, opp NC9 A53 Part of the Newport-Sandown Cycle NC8 Track Langbridge, opp NC8 NC53 Part of the Newport-Sandown Cycle NC9 Track NC10 B35 / NC45A NC53 NC11 The Shute @ Parsonage NC53 / B54 Farm NC11B Skinner Hill @ Hill Top NC11 @ Hill Heath NC11C NC11B @ Hill Heath NC11 NC12 Youngwoods Way / NC11 Alverstone Road / Alverstone Shute NC13 Newchurch High Street / Palmers Lane / Skinners School Lane Hill NC14 Palmers Lane Dyers Lane Path obstructed not walkable NC15 Skinners Hill Alverstone Road NC16 Winford Road Alverstone Road NC17 Alverstone Main Road, opp Burnthouse Lane / NC44 Alverstone squirrel hide NC42 / youngwoods Way NC18 Burnthouse Lane / NC44 SS48 NC19 Alverstone Road NC20 / NC21 NC20 Alverstone Road / SS54 @ Cheverton Farm Borthwood Copse Borthwood Lane campsite NC21 Alverstone Road NC19 / NC20 / NC21 NC22 Borthwood Lane, opp NC19 NC22A @ Embassy Way Sandown airport @ Beaulieu Cottages runway ________________ SS30 @ Scotchells Brook SS28 @ Sandown Air Port NC22A NC22 / NC22B @ Embassy NC22 / SS25 Way Scotchells Brook Lane / NC22 / NC22A Known as Embassy Way – Sandown NC22B airport NC23 @ Embassy Way NC23 Borthwood Lane, opp Scotchells Brook Lane / SS57 NC24 Hale Common (A3056) @ Winford