HEAP for Isle of Wight Rural Settlement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gatcombe House G a T C O M B E P a R K • I S L E O F W I G H T Gatcombe House Gatcombe Park • Isle of Wight

GATCOMBE HOUSE G A T C O M B E P A R K • I S L E O F W I G H T GATCOMBE HOUSE GATCOMBE PARK • ISLE OF WIGHT Newport: 3 miles • Cowes 9 miles • Fishbourne Ferry 9.5 miles (Portsmouth Harbour from 45 mins) Battersea Heliport 35 mins (All mileages and time approximate) An exemplar of Georgian elegance ACCOMMODATION Entrance porch • Reception hall • Drawing room • Dining room • Billiard room • Study • Office Sitting room • Gymnasium • Kitchen/breakfast room • Preparation kitchen • Staircase hall Utility room • Cloakroom • Extensive cellars Main bedroom with adjoining bathroom and dressing room with separate loo Two further bedrooms with adjoining bathrooms • Additional six bedrooms and bathrooms One bedroom staff flat • Studio The Coach House: Entrance hall • Kitchen/living room • Sitting room • Utility room • Loo Artist’s studio • Two studies • Main bedroom with adjoining bathroom Three further bedrooms and bathroom • Garden Stable Cottage: Entrance hall • Kitchen/living room • Main bedroom with adjoining bathroom Two further bedrooms and bathroom • Loo • Garden Formal gardens and lawns • Rose garden • Parkland • Pastureland • Woodland Walled courtyard with greenhouse and herb borders • Ornamental lake • Specimen and ornamental trees Grade II listed bridge • Swimming Pool • Pavilion • Tennis court • Garaging and outbuildings Extensive agricultural buildings with adjoining field In all about 48 acres (19.35 hectares) George Nares Steven Moore Savills Country Department Savills Winchester [email protected] [email protected] 020 7016 3822 01962 834 010 Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the text HISTORY Gatcombe Park estate has an exciting and colourful history with records preceding the Norman Conquest and the village of Gatcombe is listed in the Domesday Book. -

Issue 24 Autumn 2019

Quarr Abbey Issue 24 NEWSLETTER Autumn 2019 Unity of Life The man had just parked his bicycle and was taking off his helmet when, seeing me, he sort of abruptly asked: “Tell me, Father: What should I do so that Friends of Quarr what I do when I am praying in this amazing church and what I do outside The Friends are pleased to report that become one thing?” – “Good question”, I replied “How can our life be ‘one’?” the retiring collection from the Concert This question concerns all, but in a sense, it lies at the heart of monastic of Sacred Music, performed in the identity. The monk strives for unity. The Latin word monachus, which gave Abbey Church by the Orpheus Singers the English ‘monk’, comes from the Greek ‘monos’: ‘one’. The monks’ life in aid of our Accessible Paths Project, tends towards unity. They pursue it and already manifest it: a community at amounted to £712. The Gift Aid of £118 prayer is a sign of unity. will go to the abbey. It is not always easy, though. On the one hand, one has to consent to positive I would like to thank the Orpheus Singers on behalf of the Friends for tensions such as prayer and work; solitude and community; retreat and performing the concert and helping us hospitality. At first, they may be seen as tearing us apart. Well managed, they with our fundraising efforts in aid of this actually create a dynamic. The different poles of our lives begin to enrich one project. another. -

Planning and Infrastructure Services

PLANNING AND INFRASTRUCTURE SERVICES The following planning applications and appeals have been submitted to the Isle of Wight Council and can be viewed online https://www.iow.gov.uk/Residents/Environment-Planning-and-Waste/Planning/Planning-Development/Applic ation-search-view-and-comment using the link labelled ‘planning register’. Comments on the applications must be received within 21 days from the date of this press list, and comments for agricultural prior notification applications must be received within 7 days to ensure they be taken into account within the officer report. Comments on planning appeals must be received by the Planning Inspectorate within 5 weeks of the appeal start date (or 6 weeks in the case of an Enforcement Notice appeal). Details of how to comment on an appeal can be found (under the relevant LPA reference number) at https://www.iow.gov.uk/Residents/Environment-Planning-and-Waste/Planning/Planning-Development/Applic ation-search-view-and-comment For householder, advertisement consent or minor commercial (shop) applications, in the event of an appeal against a refusal of planning permission, representations made about the application will be sent to Planning Inspectorate, and there will be no further opportunity to comment at appeal stage. Should you wish to withdraw a representation made during such an application, it will be necessary to do so in writing within 4 weeks of the start of an appeal. All written representations relating to applications will be made available to view online. PLEASE NOTE THAT APPLICATIONS -

STENBURY FEDERATION Interim Executive Headteacher: Mr M Snow Chair of Governors: Mrs D Barker [email protected]

STENBURY FEDERATION Interim Executive Headteacher: Mr M Snow Chair of Governors: Mrs D Barker [email protected] Chillerton & Rookley Primary Godshill Primary Main Road, Chillerton School Road, Godshill Isle of Wight, PO30 3EP Isle of Wight, PO38 3HJ Tel. 01983 721207 Tel. 01983 840246 [email protected] [email protected] Wednesday 14th July 2021 Re: Godshill Class Structure for September 2021 Dear Parents and Carers, We are really looking forward to the end of term and a well-earned rest. Many of you will be wanting to know which classes and teachers your children will be having. The class structure for September will be: Class Class Name Teacher / Lead Support Staff Entrance to School Nursery Bembridge Windmill Marie Seaman Jim Palmer Nursery Gate Kate McKenzie Alana Monroe Reception Calbourne Mill Mrs Polly Smith Dawn Sargent Reception Gate – Lizzie Burden Car park Year 1/2 Osbourne House Miss Kirsty Hart Wendy Whitewood Main Entrance Year 2/3 The Needles Mr Conner Knight Lisa Young Main Entrance Brogan Bodman Year 4/5 Carisbrooke Castle Mrs Westhorpe and Jodie Wendes Car park side Mrs Tombleson entrance Year 5 Yarmouth Castle Mr Tim Smith Chantelle De’ath Steps side of school Lauren Shaw-Yates Year 6 St Catherine’s Mrs Boakes Danny Chapman Steps side of school Oratory Any pupils that are in the mixed class of Year 1/2 or 4/5 that are in Year 2 or 5 will be contacted individually by the school. School will start at 8:45am for all pupils. School finishes for all pupils at 3:00pm, except for Reception, who will finish at 2:55pm. -

Post-Medieval and Modern Resource Assessment

THE SOLENT THAMES RESEARCH FRAMEWORK RESOURCE ASSESSMENT POST-MEDIEVAL AND MODERN PERIOD (AD 1540 - ) Jill Hind April 2010 (County contributions by Vicky Basford, Owen Cambridge, Brian Giggins, David Green, David Hopkins, John Rhodes, and Chris Welch; palaeoenvironmental contribution by Mike Allen) Introduction The period from 1540 to the present encompasses a vast amount of change to society, stretching as it does from the end of the feudal medieval system to a multi-cultural, globally oriented state, which increasingly depends on the use of Information Technology. This transition has been punctuated by the protestant reformation of the 16th century, conflicts over religion and power structure, including regicide in the 17th century, the Industrial and Agricultural revolutions of the 18th and early 19th century and a series of major wars. Although land battles have not taken place on British soil since the 18th century, setting aside terrorism, civilians have become increasingly involved in these wars. The period has also seen the development of capitalism, with Britain leading the Industrial Revolution and becoming a major trading nation. Trade was followed by colonisation and by the second half of the 19th century the British Empire included vast areas across the world, despite the independence of the United States in 1783. The second half of the 20th century saw the end of imperialism. London became a centre of global importance as a result of trade and empire, but has maintained its status as a financial centre. The Solent Thames region generally is prosperous, benefiting from relative proximity to London and good communications routes. The Isle of Wight has its own particular issues, but has never been completely isolated from major events. -

Historic Environment Action Plan the Undercliff

Directorate of Community Services Director Sarah Mitchell Historic Environment Action Plan The Undercliff Isle of Wight County Archaeology and Historic Environment Service October 2008 01983 823810 archaeology @iow.gov.uk Iwight.com HEAP for the Undercliff. INTRODUCTION This HEAP Area has been defined on the basis of geology, topography, land use and settlement patterns which differentiate it from other HEAP areas. This document identifies essential characteristics of the Undercliff as its geomorphology and rugged landslip areas, its archaeological potential, its 19 th century cottages ornés /marine villas and their grounds, and the Victorian seaside resort character of Ventnor. The Area has a highly distinctive character with an inner cliff towering above a landscape (now partly wooded) demarcated by stone boundary walls. The most significant features of this historic landscape, the most important forces for change and key management issues are considered. Actions particularly relevant to this Area are identified from those listed in the Isle of Wight HEAP Aims, Objectives and Actions. ANALYSIS AND ASSESSMENT Location, Geology and Topography • The Undercliff is identified as a discrete Landscape Character Type in the Isle of Wight AONB Management Plan (2004, 132). • The Area lies to the south of the South Wight Downland , from which it is separated by vertical cliffs forming a geological succession from Ferrugunious Sands through Sandrock, Carstone, Gault Clay, Upper Greensand, Chert Beds and Lower Chalk (Hutchinson 1987, Fig. 6). o The zone between the inner cliff and coastal cliff is a landslip area o This landslip is caused by groundwater lubrication of slip planes within the Gault Clays and Sandrock Beds. -

Schedule 2019 24/06/19 2 23/12/19 OFF

Mobile Library Service Weeks 2019 Mobile Mobile Let the Library come Library Library w / b Week w / b Week Jan 01/01/19 HLS July 01/07/19 HLS to you! 07/01/19 HLS 08/07/19 HLS 14/01/9 1 15/07/19 1 21/01/19 2 22/07/19 2 28/01/19 HLS 29/07/19 HLS Feb 04/02/19 HLS Aug 05/08/19 HLS 11/02/19 1 12/08/19 1 18/02/19 2 19/08/19 2 25/02/19 HLS 26/08/19* HLS Mar 04/03/19 HLS Sept 02/09/19 HLS 11/03/19 1 09/09/19 1 18/03/19 2 16/09/19 2 25/03/19 HLS 23/09/19 OFF April 01/04/19 HLS 30/09/19 HLS 08/04/19 1 Oct 07/10/19 15/04/19 2 14/10/19 22/04/19 OFF 21/10/19 29/04/19 HLS 28/10/19 May 06/05/19* HLS Nov 04/11/19 13/05/19 1 11/11/19 20/05/19 2 18/11/19 OFF 27/05/19* OFF 25/11/19 June 03/06/19 HLS Dec 02/12/19 10/06/19 1 09/12/19 17/06/19 HLS 16/12/19 Schedule 2019 24/06/19 2 23/12/19 OFF 06/05/19—May Day Bank Holiday 27/05/19—Whitsun Bank Holiday 26/08/19—August Bank Holiday The Home Library Service (HLS) operates on weeks when the Mobile Library is not on the road. -

Historic Environment Action Plan West Wight Chalk Downland

Directorate of Community Services Director Sarah Mitchell Historic Environment Action Plan West Wight Chalk Downland Isle of Wight County Archaeology and Historic Environment Service October 2008 01983 823810 archaeology @iow.gov.uk Iwight.com HEAP for West Wight Chalk Downland. INTRODUCTION The West Wight Chalk Downland HEAP Area has been defined on the basis of geology, topography and historic landscape character. It forms the western half of a central chalk ridge that crosses the Isle of Wight, the eastern half having been defined as the East Wight Chalk Ridge . Another block of Chalk and Upper Greensand in the south of the Isle of Wight has been defined as the South Wight Downland . Obviously there are many similarities between these three HEAP Areas. However, each of the Areas occupies a particular geographical location and has a distinctive historic landscape character. This document identifies essential characteristics of the West Wight Chalk Downland . These include the large extent of unimproved chalk grassland, great time-depth, many archaeological features and historic settlement in the Bowcombe Valley. The Area is valued for its open access, its landscape and wide views and as a tranquil recreational area. Most of the land at the western end of this Area, from the Needles to Mottistone Down, is open access land belonging to the National Trust. Significant historic landscape features within this Area are identified within this document. The condition of these features and forces for change in the landscape are considered. Management issues are discussed and actions particularly relevant to this Area are identified from those listed in the Isle of Wight HEAP Aims, Objectives and Actions. -

Land at Borthwood Lane | Newchurch | Sandown | PO36 OHH Guide Price £48,000

Land at Borthwood Lane | Newchurch | Sandown | PO36 OHH Guide Price £48,000 An area of land which extends to approximately 5 acres and is Freehold. The land is currently Approximately 5 Acres of pasture and has easy access to the Island's extensive bridleway network. The land is partly Land hedged and fenced. The neighbouring Borthwood Copse (National Trust) is a Site of Important Currently used as Pasture Nature Conservation (S.I.N.C.) and is home to many species of wildlife including the Island's Land well-known red squirrels. Access to Bridleways Secure gated entrance Property Description From Newport take the A3056 signal to Sandown. Proceed through Arreton an at Thompson Nursery and turn left into An area of land which extends to approximately 5 acres and is Watery Lane. At the cross roads go straight ahead into Forest Freehold. The land is currently pasture and has easy access to the Island's extensive bridleway network. The land is partly hedged and Road and then left into Alverstone Road. Do not turn left into fenced. The neighbouring Borthwood Copse (National Trust) is a Site Skinners Hill; Borthwood Lane will be found on the right hand of Important Nature Conservation (S.I.N.C.) and is home to many side. Turn into the lane and the Land will be found on the right species of wildlife including the Island's well-known red squirrels. side after 300m Newchurch Newchurch is a very popular village in the south east of the Viewing arrangements Island about 8 miles from Island’s main shopping and Viewing is strictly by appointment with the Sole Agents Biles & administrative centre of Newport. -

Charles I: the Court at War

6TH NOVEMBER 2019 Theatres of Revolution: the Stuart Kings and the Architecture of Disruption – Charles I: The Court at War PROFESSOR SIMON THURLEY In my last lecture I described what happened when through choice or catastrophe a monarch cannot rule or live in the palaces and places designed for it. King James I subverted English courtly conventions and established a series of unusual royal residences that gave him privacy and freedom from conventional royal etiquette. Although court protocol prevailed at Royston, there was none of the grandeur that the Tudor monarchs would have expected. Indeed, from our perspective Royston was not a palace at all, just a jumble of houses in a market town. Today we turn our attention to King Charles I. In a completely different way from his father he too ended up living in places which we would hesitate to call palaces. But the difference was that he strove at every turn to maintain the magnificence and dignity due to him as sovereign. On 22 August 1642 King Charles raised his standard at Nottingham signalling the end of a stand-off with Parliament and the beginning of what became Civil War. Since the 10th January, when Charles had abandoned London, after his botched attempt to arrest five members of parliament, he had been on the move. Hastily exiting from Whitehall, he arrived late at Hampton Court which was quite unprepared to receive the royal family; it was cold and only partially furnished when Charles entered his privy lodgings. But the king’s main concern was security, not comfort, and preparations were undertaken at lightning speed for the king and queen to move to the safety of Windsor Castle. -

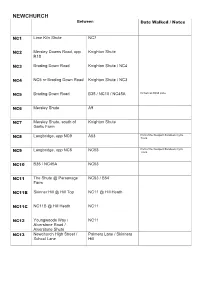

NEWCHURCH Between Date Walked / Notes

NEWCHURCH Between Date Walked / Notes NC1 Lime Kiln Shute NC7 NC2 Mersley Downs Road, opp Knighton Shute R18 NC3 Brading Down Road Knighton Shute / NC4 NC4 NC5 nr Brading Down Road Knighton Shute / NC3 NC5 Brading Down Road B35 / NC10 / NC45A Known as Blind Lane NC6 Mersley Shute A9 NC7 Mersley Shute, south of Knighton Shute Garlic Farm Langbridge, opp NC9 A53 Part of the Newport-Sandown Cycle NC8 Track Langbridge, opp NC8 NC53 Part of the Newport-Sandown Cycle NC9 Track NC10 B35 / NC45A NC53 NC11 The Shute @ Parsonage NC53 / B54 Farm NC11B Skinner Hill @ Hill Top NC11 @ Hill Heath NC11C NC11B @ Hill Heath NC11 NC12 Youngwoods Way / NC11 Alverstone Road / Alverstone Shute NC13 Newchurch High Street / Palmers Lane / Skinners School Lane Hill NC14 Palmers Lane Dyers Lane Path obstructed not walkable NC15 Skinners Hill Alverstone Road NC16 Winford Road Alverstone Road NC17 Alverstone Main Road, opp Burnthouse Lane / NC44 Alverstone squirrel hide NC42 / youngwoods Way NC18 Burnthouse Lane / NC44 SS48 NC19 Alverstone Road NC20 / NC21 NC20 Alverstone Road / SS54 @ Cheverton Farm Borthwood Copse Borthwood Lane campsite NC21 Alverstone Road NC19 / NC20 / NC21 NC22 Borthwood Lane, opp NC19 NC22A @ Embassy Way Sandown airport @ Beaulieu Cottages runway ________________ SS30 @ Scotchells Brook SS28 @ Sandown Air Port NC22A NC22 / NC22B @ Embassy NC22 / SS25 Way Scotchells Brook Lane / NC22 / NC22A Known as Embassy Way – Sandown NC22B airport NC23 @ Embassy Way NC23 Borthwood Lane, opp Scotchells Brook Lane / SS57 NC24 Hale Common (A3056) @ Winford -

WALKING EXPERIENCES: TOP of the WIGHT Experience Sustainable Transport

BE A WALKING EXPERIENCES: TOP OF THE WIGHT Experience sustainable transport Portsmouth To Southampton s y s rr Southsea Fe y Cowe rr Cowe Fe East on - ssenger on - Pa / e assenger l ampt P c h hi Southampt Ve out S THE EGYPT POINT OLD CASTLE POINT e ft SOLENT yd R GURNARD BAY Cowes e 5 East Cowes y Gurnard 3 3 2 rr tsmouth - B OSBORNE BAY ishbournFe de r Lymington F enger Hovercra Ry y s nger Po rr as sse Fe P rtsmouth/Pa - Po e hicl Ve rtsmouth - ssenger Po Rew Street Pa T THORNESS AS BAY CO RIVE E RYDE AG K R E PIER HEAD ERIT M E Whippingham E H RYDE DINA N C R Ve L Northwood O ESPLANADE A 3 0 2 1 ymington - TT PUCKPOOL hic NEWTOWN BAY OO POINT W Fishbourne l Marks A 3 e /P Corner T 0 DODNOR a 2 0 A 3 0 5 4 Ryde ssenger AS CREEK & DICKSONS Binstead Ya CO Quarr Hill RYDE COPSE ST JOHN’S ROAD rmouth Wootton Spring Vale G E R CLA ME RK I N Bridge TA IVE HERSEY RESERVE, Fe R Seaview LAKE WOOTTON SEAVIEW DUVER rr ERI Porcheld FIRESTONE y H SEAGR OVE BAY OWN Wootton COPSE Hamstead PARKHURST Common WT FOREST NE Newtown Parkhurst Nettlestone P SMALLBROOK B 4 3 3 JUNCTION PRIORY BAY NINGWOOD 0 SCONCE BRIDDLESFORD Havenstreet COMMON P COPSES POINT SWANPOND N ODE’S POINT BOULDNOR Cranmore Newtown deserted HAVENSTREET COPSE P COPSE Medieval village P P A 3 0 5 4 Norton Bouldnor Ashey A St Helens P Yarmouth Shaleet 3 BEMBRIDGE Cli End 0 Ningwood Newport IL 5 A 5 POINT R TR LL B 3 3 3 0 YA ASHEY E A 3 0 5 4Norton W Thorley Thorley Street Carisbrooke SHIDE N Green MILL COPSE NU CHALK PIT B 3 3 9 COL WELL BAY FRES R Bembridge B 3 4 0 R I V E R 0 1