(ALERT ) on Attitudes and Confidence in Managing Critically Ill Adult Patients

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SOUTH WEST Newquay Beach Newquay, Facing the Atlantic Ocean

SOUTH WEST Newquay Beach Newquay, facing the Atlantic Ocean on the North Cornwall Coast, is the largest resort in Cornwall. There are many different beaches to choose from including: Towan Beach, Fistral Beach, Lusty Glaze, Holywell Bay and Crantock. Reachable by a stiff walk from the village of West Pentire, is Porth Joke, also known as Polly Joke, a delightful suntrap of a beach, surrounded by low cliffs, some with sea caves, unspoilt and popular with families. A stream runs down the valley, and open fields and low dunes lead right onto the head of the beach. The beach is popular with body boarders. Often cattle from the nearby Kelseys, an ancient area of springy turfed grassland, rich in wildflowers, can be found drinking from the stream. Beyond the headland is Holywell Bay arguably one of the most beautiful beaches in Cornwall, backed by sand dunes framed by the Gull Rocks off shore. Reachable by a 15 minute walk from the Car Park. It is a nice walk west along the Coast to Penhale Point, with superb views across Perran Bay, with Perranporth in the middle distance. Nearest Travelodge: Stay at the St Austell Travelodge, Pentewan Road, St Austell, Cornwall, PL25 5BU from as little as £29 per night, best deals can be found online at www.travelodge.co.uk Clifton Suspension Bridge- Bristol The Clifton Suspension Bridge, is the symbol of the city of Bristol. Stroll across for stunning views of the Avon gorge and elegant Clifton. For almost 150 years this Grade I listed structure has attracted visitors from all over the world. -

Screening Review of the Bournemouth, Dorset and Poole Minerals Strategy 2014

Cabinet 8 September 2020 Screening Review of the Bournemouth, Dorset and Poole Minerals Strategy 2014 For Decision Portfolio Holder: Cllr D Walsh, Planning Local Councillor(s): All Wards Executive Director: John Sellgren, Executive Director of Place Report Author: Trevor Badley Title: Lead Project Officer (Minerals & Waste) Tel: 01305 224675 Email: [email protected] Report Status: Public Recommendation: That: i) it be noted that following Screening of the Bournemouth, Dorset and Poole Minerals Strategy 2014 for Review, a full or partial Review of the Minerals Strategy will not be undertaken this year. Officers will continue monitoring the Minerals Strategy 2014 and it will be screened again in 2021. ii) the Dorset Council Local Development Scheme is updated accordingly to reflect these actions. iii) the 2020 Review of the Bournemouth, Dorset and Poole Minerals Strategy 2014 , attached as an Appendix to this report, is made publicly available. Reason for Recommendation: Paragraph 33 of the National Planning Policy Framework 2019 requires that a local plan should be reviewed after five years to consider whether a formal full or partial Plan Review is required. To ensure that Dorset Council complies with this requirement, the Bournemouth, Dorset and Poole Minerals Strategy 2014 was screened to assess whether a full or partial Review was required. It was found that a Review did not need to be initiated this year. The Dorset Council Local Development Scheme needs to be updated to reflect this, and planning guidance requires that the report of the screening exercise is made publicly available. 1. Executive Summary The Bournemouth, Dorset and Poole Minerals Strategy 2014 (MS) was adopted more than five years ago, and as required by the National Planning Policy Framework 2019 it has been assessed to determine whether a formal full (the whole document) or partial (only selected policies) Review is required. -

Bournemouth & Poole Seafront Map And

Chill out in our American diner with sea views! Delicious food and cocktails served all day EVENT VENUE HIRE BEACH HUTS HISTORIC PIERS BEACH SAFETY The Prom Diner, Boscombe Promenade, Undercliff Drive, Boscombe, BH5 1BN Monday - Sunday from 9am until late (weather dependant) The Branksome Dene Room is the ultimate back drop Our traditional beach huts are available for hire along Whether you’re looking for family fun or a relaxing Our beaches are some of the safest in the country BOURNEMOUTH & to your private or corporate event and is set above ten miles of stunning Bournemouth and Poole coastline stroll, visit our historic seaside piers. At Bournemouth with professional RNLI beach lifeguards operating Poole’s beautiful award winning beaches. The room from Southbourne to Sandbanks. Beach huts are perfect Pier, enjoy a bite to eat and take in the stunning during the season. There are zones for swimmers is a licensed venue for civil ceremonies and a flexible for taking in the spectacular sea views or simply relaxing seaside scenery at Key West Restaurant, while the kids and windsurfers with lifeguard patrols and ‘Baywatch’ POOLE SEAFRONT space that allows you to create the perfect gathering and watching the world go by. let off some steam at RockReef, the indoor climbing towers to ensure a safe, fun and relaxing time. Rangers or meeting. Features include: and high wire activity centre. Why not also enjoy a regularly patrol seafront areas throughout the year. PierView Room for hire! few games at the Pier Amusements or an exhilarating MAP AND • Seating capacity for 50 people or 80 including patio Sun Safety slip-slap-slop: slip on a t-shirt, slap on a bournemouth.co.uk/pierviewroom pier-to-shore zip wire?! Private venue hire situated on the seafront, adjacent to The Prom Diner • Preparation area for food hat, and slop on the sunscreen. -

South Western Main Line: Southampton - Bournemouth

Train Simulator – South Western Main Line: Southampton - Bournemouth South Western Main Line: Southampton - Bournemouth © Copyright Dovetail Games 2019, all rights reserved Release Version 1.0 Page 1 Train Simulator – South Western Main Line: Southampton - Bournemouth Contents 1 Route Map ............................................................................................................................................ 4 2 Rolling Stock ........................................................................................................................................ 5 3 Driving the Class 444 & Class 450 ...................................................................................................... 7 Cab Controls ....................................................................................................................................... 7 Key Layout .......................................................................................................................................... 8 Class 444/450 Sander ......................................................................................................................... 8 Class 444/450 Power Reduction Button ............................................................................................. 8 5 Driving the LNER A2 60532 “Blue Peter”............................................................................................. 9 Cab Controls ...................................................................................................................................... -

Bournemouth Destination Report

Bournemouth destination report 1 VisitEngland Destination tracker: • Since April 2015, the national tourist boards of VisitEngland, VisitScotland and VisitWales have been tracking visitor perceptions of holiday destinations across GB in a single research vehicle. • Data in this report is from April 2015 – September 2016 • This study explores behavioural and experience measures such as, visitation, spend, stay length, satisfaction and advocacy within individual destinations. As well as the imagery perceptions of each destination. • In the report there are 3 samples for comparison; those from whom this destination was the most recently visited, those who claim to visit a seaside destination at C52 and finally a GB average. • All respondents are GB holiday takers, having taken a GB break in the past 12 months or are expecting to in the next 12 months. This accounts for approx. 49% of the population. • Significant differences will be indicated by a black↑/orange↓ arrow against seaside destinations and a blue↑/red↓ against GB. • This report provides a snapshot of: 1. A demographic split of destination visitors 2. The behaviours exhibited at the destination: How loyal are they to the destination and how satisfied were they with their trip? 3. How GB holiday makers perceive this destination and how does it compare with others? • Finally there is a summary of findings. 2 Who is visiting? Ever Visited Bournemouth : Visited destination in the last 3 years Region of Bournemouth Seaside Great Britain origin Wales 4% 6% 5% 58% Gender Bournemouth Seaside -

PLAN for CHILDREN, YOUNG PEOPLE and THEIR FAMILIES December 2016 - March 2020

PLAN FOR CHILDREN, YOUNG PEOPLE AND THEIR FAMILIES December 2016 - March 2020 Working in partnership for 1 children, young people & families Plan for Children, Young People and their Families 2016 – 2020 This is the 2016 refresh of our Plan for Children, Young People and their Families 2014-2017 All photographs throughout this publication are of Bournemouth children, used with permission Alternative formats can be provided. For language translations or large print, please contact: 01202 456222 or [email protected] Plan for Children, Young People and their Families 2016 – 2020 Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Mission, Vision and Principles .................................................................................................................. 4 The National Context ............................................................................................................................ 5 The Local Context ................................................................................................................................ 7 The Plan ........................................................................................................................................... 10 What we know and what we are going to do about it ............................................................................. 12 Ensuring Delivery of our Plan .................................................................................................................. -

South West Peninsula Route Strategy March 2017 Contents 1

South West Peninsula Route Strategy March 2017 Contents 1. Introduction 1 Purpose of Route Strategies 2 Strategic themes 2 Stakeholder engagement 3 Transport Focus 3 2. The route 5 Route Strategy overview map 7 3. Current constraints and challenges 9 A safe and serviceable network 9 More free-flowing network 9 Supporting economic growth 9 An improved environment 10 A more accessible and integrated network 10 Diversionary routes 15 Maintaining the strategic road network 16 4. Current investment plans and growth potential 17 Economic context 17 Innovation 17 Investment plans 17 5. Future challenges and opportunities 23 6. Next steps 31 i R Lon ou don to Scotla te nd East London Or bital and M23 to Gatwick str Lon ategies don to Scotland West London to Wales The division of rou tes for the F progra elixstowe to Midlands mme of route strategies on t he Solent to Midlands Strategic Road Network M25 to Solent (A3 and M3) Kent Corridor to M25 (M2 and M20) South Coast Central Birmingham to Exeter A1 South West Peninsula London to Leeds (East) East of England South Pennines A19 A69 North Pen Newccaastlstlee upon Tyne nines Carlisle A1 Sunderland Midlands to Wales and Gloucest M6 ershire North and East Midlands A66 A1(M) A595 South Midlands Middlesbrougugh A66 A174 A590 A19 A1 A64 A585 M6 York Irish S Lee ea M55 ds M65 M1 Preston M606 M621 A56 M62 A63 Kingston upon Hull M62 M61 M58 A1 M1 Liver Manchest A628 A180 North Sea pool er M18 M180 Grimsby M57 A616 A1(M) M53 M62 M60 Sheffield A556 M56 M6 A46 A55 A1 Lincoln A500 Stoke-on-Trent A38 M1 Nottingham -

HMO Register

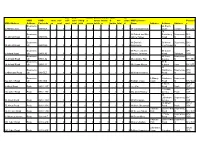

non- bedr permi permit-shared- share wc- HMO HMO store self- self- oom- living- t- house kitche d- wc- share HMO Licensee Postcod HMO Address Address Postcode ys cont cont total total occup holds n bathro total d Name Address Address Address e Bournemo 26 South 5 Abbott Close uth BH9 1EX 2 0 5 5 1 5 5 1 1 1 1 Mr Christopher Ely Close London N6 5UQ 18 Bournemo Mr Robert and Mrs Saxonbury Bournemou BH6 34 Abbott Road uth BH9 1HA 2 0 5 5 1 5 5 1 3 0 2 Janice Halsey Road th 5NB Bournemo Mr Dominik 59 Heron Bournemou BH9 40 Abbott Road uth BH9 1HA 2 0 5 5 1 5 5 1 2 0 2 Kaczmarek Court Road th 1DF Bournemo Mr Peter and Mrs 65 Castle SP1 5 Acland Road uth BH9 1JQ 2 0 5 5 1 5 5 1 2 0 2 Joanne Jennings Road Salisbury 3RN Bournemo 48 Cecil Bournemou 53 Acland Road uth BH9 1JQ 2 0 5 5 1 5 5 1 2 0 2 Ms Caroline Trist Avenue th BH8 9EJ Bournemo 91 St 66 Acland Road uth BH9 1JJ 2 0 5 5 1 5 5 1 2 0 1 Ms Susan Noone Aubyns Hove BH3 2TL 83 Bournemo Wimborne Bournemou BH3 6 Albemarle Road uth BH3 7LZ 2 0 6 6 1 0 0 1 1 0 2 Mr Nick Gheissari Road th 7AN 9 Bournemo 9 Albany Wimborne Bournemou 12a Albert Road uth BH1 1BZ 4 0 6 6 1 6 6 1 2 0 4 Rodrigo Costa Court Road th BH2 6LX 8 Albert BH12 8 Albert Road Poole BH12 2BZ 2 0 5 5 0 5 5 1 0 5 0 Lee Vine Road Poole 2BZ 1 Glenair BH14 20a Albert Road Poole BH12 2BZ 2 0 6 6 1 6 6 1 3 0 3 Mrs Anita Bowley Avenue Poole 8AD 44 Littledown Bournemou BH7 53 Albert Road Poole BH12 2BU 2 0 6 6 1 6 6 1 2 2 2 Mr Max Goode Avenue th 7AP 75 Albert BH12 75 Albert Road Poole BH12 2BX 2 0 7 7 0 7 7 1 1 1 2 Mr Mark Sherwood Road -

The Isle of Wight in the English Landscape

THE ISLE OF WIGHT IN THE ENGLISH LANDSCAPE: MEDIEVAL AND POST-MEDIEVAL RURAL SETTLEMENT AND LAND USE ON THE ISLE OF WIGHT HELEN VICTORIA BASFORD A study in two volumes Volume 1: Text and References Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Bournemouth University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2013 2 Copyright Statement This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and due acknowledgement must always be made of the use of any material contained in, or derived from, this thesis. 3 4 Helen Victoria Basford The Isle of Wight in the English Landscape: Medieval and Post-Medieval Rural Settlement and Land Use Abstract The thesis is a local-scale study which aims to place the Isle of Wight in the English landscape. It examines the much discussed but problematic concept of ‘islandness’, identifying distinctive insular characteristics and determining their significance but also investigating internal landscape diversity. This is the first detailed academic study of Isle of Wight land use and settlement from the early medieval period to the nineteenth century and is fully referenced to national frameworks. The thesis utilises documentary, cartographic and archaeological evidence. It employs the techniques of historic landscape characterisation (HLC), using synoptic maps created by the author and others as tools of graphic analysis. An analysis of the Isle of Wight’s physical character and cultural roots is followed by an investigation of problems and questions associated with models of settlement and land use at various scales. -

Bournemouth & Isle of Wight

P2020 England_Brochure A4 17/02/2020 09:15 Page 39 ENGLAND ENGLAND BBoouurrnneemmoouutthh && IIssllee OOff WWiigghhtt Bournemouth Isle Of Wight Tour Stratford Upon Avon Southampton Salisbury The New Forest Bath Solent Cruise Holiday Itinerary Sands Hotel Day 1: Join your tour Dublin City Centre or Full Day - New Forest, Southampton ★★★ at Dublin Ferryport for the short sea crossing & Lyndhurst ★★★ to Holyhead. On arrival in Holyhead we join Our tour takes us into the New Forest as we Located on the west cliff, just a short stroll from our coach and depart for our hotel in the West head to the village of Lyndhurst where Alice Bournemouth town centre and close to the cliff top Midlands for dinner and overnight stay. Liddell, the inspiration for Alice In park which offers panoramic sea views stretching from the Isle Of Wight to Pool and beyond. The Day 2: After breakfast we depart our hotel Wonderland, is buried. We continue on tour Sands Hotel has a sun terrace at the front of the for Bournemouth in Dorset the South of to the city of Southampton with its hotel, lift, coffee shop, 2 guest lounges, bar and England. Travelling through the Warwickshire prestigious harbour. Free time for personal pool table. Hotel entertainment suite features dance floor and live nightly entertainment. All countryside to Stratford Upon Avon and sightseeing before returning to our hotel for evening dinner and overnight . bedrooms are ensuite, flatscreen TV. Free WiFi in onwards visiting Salisbury and one of the public areas. finest medieval Cathedrals in Britain today. Full Day - The Isle Of Wight & Nightly Entertainment Featuring the tallest spire in Britain the Scenic Solent Cruise Chapter House holds the original Magna We drive to Ocean Village at Southampton Carta. -

Bournemouth's Climate Change Strategy

A CLIMATE CHANGE STRATEGY FOR BOURNEMOUTH 2016-2020 Bournemouth Action Help us increase global resilience on Climate Change: and reach our target of a 30% reduction What you can do in CO2 by 2020. If you work in Bournemouth: Turn off equipment when Car share, cycle, walk or use public Join the Bournemouth Food not in use transport to get to work Assembly and collect fresh, local produce in the town centre If you live in Bournemouth: Insulate your loft and Install renewable energy Grow some of your own food cavity walls If you visit Bournemouth: Look out for locally produced Use public transport, Take your litter home or recycle and Fairtrade food cycle or walk in our segregated bins If you go to school in Bournemouth: Walk, cycle or scoot Encourage your school Make your school a to school to be an Eco-School Fairtrade School If you run a business in Bournemouth: Buy green energy from your Join the Dorset Green Request a free waste audit energy company Business Network from the Council How Bournemouth is tackling Climate Change Green infrastructure: protecting parks, trees, Built infrastructure: gardens and countryside Sustainable food: improving the resilience of roads encouraging local food and buildings production and long Making Changes (Adaptation) term security Bournemouth is adapting for the extreme weather changes that are happening now and in the near future. We expect Bournemouth to be warmer with more intense rainfall and more frequent storms. We are working on the priority areas shown here: Public health: Council: Preventing -

Western Gateway Sub-National Transport Body

Western Gateway Sub-national Transport Body Regional Evidence Base and MRN / LLM Scheme Priorities July 2019 Western Gateway Sub-national Transport Body Regional Evidence Base & MRN / LLM Scheme Priorities – July 2019 This document has been produced with the help and support of the following local authority officers. The process of producing this has demonstrated true collaboration and partnership working: Alexis Edwards James White Alice Jennings Jason Humm Allan Creedy Julian McLaughlin Andrew Davies Kate Baldwin Arina Salhorta Kelvin Packer Bella Fortune Laura Russ Ben Watts Louise Fradd Bill Cotton Luisa Senft-Hayward Bill Davies Mandy Bishop Colin Chick Nigel Riglar Colin Medus Nuala Gallagher David Carter Parvis Khansari David Simmons Peter Mann Elizabeth Mills Robert Murphy Emma Blackham Steven Thorne Ewan Wilson Wayne Sayers Western Gateway Sub-national Transport Body Regional Evidence Base & MRN / LLM Scheme Priorities – July 2019 WESTERN GATEWAY SUB-NATIONAL TRANSPORT BODY Regional Evidence Base and MRN / LLM Scheme Priorities This document has been produced for the Department for Transport to consider alongside the Western Gateways Major Road Network and Large Local Major funding submission. It provides an overview of the emerging Regional Evidence Base produced to support the Western Gateway’s Strategic Transport Plan. The information contained within the Regional Evidence Base shall be added to as the Strategic Transport Plan progresses. Contents Amendment Record This report has been issued and amended as follows: Issue Revision Description Date Signed 1.0 Document issued 24/07/19 BW Western Gateway Sub-national Transport Body Regional Evidence Base & MRN / LLM Scheme Priorities – July 2019 Contents 1.0 Introduction ...............................................................................................................................