View Myanmar Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

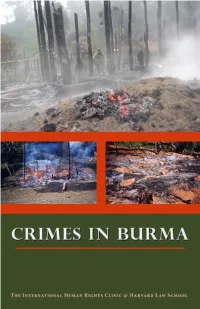

Crimes in Burma

Crimes in Burma A Report By Table of Contents Preface iii Executive Summary 1 Methodology 5 I. History of Burma 7 A. Early History and Independence in 1948 7 B. Military Rule: 1962-1988 9 C. The 1988 Popular Uprising and Democratic Elections in 1990 11 D. Military Rule Since 1988 12 II. International Criminal Law Framework 21 A. Crimes Against Humanity: Chapeau or Common Elements 24 B. War Crimes: Chapeau or Common Elements 27 C. Enumerated or Prohibited Acts 30 III. Human Rights Violations in Burma 37 A. Forced Displacement 39 B. Sexual Violence 51 C. Extrajudicial Killings and Torture 64 D. Legal Evaluation 74 ii Preface IV. Precedents for Action 77 A. The Security Council’s Chapter VII Powers 78 B. The Former Yugoslavia 80 C. Rwanda 82 D. Darfur 84 E. Burma 86 Conclusion 91 Appendix 93 Acknowledgments 103 Preface For many years, the world has watched with horror as the human rights nightmare in Burma has unfolded under military rule. The struggle for democracy of Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and other political prisoners since 1988 has captured the imagination of people around the world. The strength of Buddhist monks and their Saffron Revolution in 2007 brought Burma to the international community’s attention yet again. But a lesser known story—one just as appalling in terms of human rights—has been occurring in Burma over the past decade and a half: epidemic levels of forced labor in the 1990s, the recruitment of tens of thousands of child soldiers, widespread sexual violence, extrajudicial killings and torture, and more than a million displaced persons. -

Q&A on Elections in BURMA

Q&A ON ELECTIONS IN BURMA PHOTOGRapHS BY PLATON Q&A ON ELECTIONS IN BuRma INTRODUCTION PHOTOGRapHS BY PLATON Burma will hold multi-party elections on November 7, 2010, the first in 20 years. Some contend the elections could spark a gradual process of democratization and the opening of civil society space in Burma. Human Rights Watch believes that the elections must be seen in the context of the Burmese military government’s carefully manufactured electoral process over many years that is designed to ensure continued military rule, albeit with a civilian façade. The generals’ “Road Map to Disciplined Democracy” has been a path filled with human rights violations: the brutal crackdown on peaceful protesters in 2007, the doubling of the number of political prisoners in Burma since then to more than 2000, the marginalization of WIN MIN, CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER ethnic minority communities in border areas, a rewritten constitution that A medical student at the time, Win undermines rights and guarantees continued military rule, and carefully Min became a leader of the 1988 constructed electoral laws that subtly bar the main opposition candidates. pro-democracy demonstrations in Burma. After years fighting in the jungle, Win Min has become one of the This political repression takes place in an environment that already sharply restricts most articulate intellectuals in exile. freedom of association, assembly, and expression. Burma’s media is tightly controlled Educated at Harvard University, he is by the authorities, and many media outlets trying to report on the elections have been now one of the driving forces behind an innovative collective called the Vahu (in reduced to reporting on official announcements’ and interviews with party leaders: no Burmese: Plural) Development Institute, public opinion or opposition is permitted. -

University of Yangon Department of Anthropology

UNIVERSITY OF YANGON DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY EDUCATION AND HEALTH EDUCATION IN SITPINQUIN VILLAGE THANLYIN TOWNSHIP, YANGON SOE MOE NAiNG M.A. Antb.6 (2009-2010) YANGON MAY,20tO UNIVERSITY OF YANGON DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY EDUCATION AND HEALTH EDUCATION IN SITPINQUIN VILLAGE THANLYINTOWNSHIP, YANGON SOE MOE NAING M.A. Anth.6 (2009-2010) YANGON MAY,2010 UNIVERSITY OF YANGON DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY EDUCATION AND HEALTH EDUCAnON IN SITPINQUIN VILLAGE THANLYIN TOWNSHIP, YANGON Research Thesis is submitted for Master Degree in Anthropology Submitted By SOE MOE NAING M.A. Anth.6 ( 2009- 2010 ) YANGON 2010 EDUCATION AND HEALTH EDUCATION IN SITPINQUIN VILLAGE THANLYIN TOWNSHIP, YANGON EDUCATION AND HEALTH EDUCATION IN SITPINQUIN VILLAGE THANLYINTOWNSHlP, YANGON SOE MOE NAING M.A. Anth.6 ( 2009- 2010 ) Master Degree in Anthropology Department of Anthropology May. 2010 proved by Board of Examiners -.1:fl'-"'J'G k,J ~D:p\(\'" ............~~~. .. .... .... .. ?f.l~ . Chairperson External Examiner (Mya Mya Khln.Dr.] ( Myint Myint Aye) Associate Professor/Head Lecturer! Head Departmentof Anthropology Department ofAnthropology University ofYangon University of Dagon Supervisor Co-supervisor ( Mya Thidar Aung) ( Zin Mar Latt ) Department of Anthropology Department ofAnthropology University of Yangon University of Yangon Contents No. Particular Page Acknowledgements Abstract Key words Introduction Chapter (I) Research Methodology Data Collection 0). Key Informant Interview (ii). Interview (iii). Focus Group Interview Data Analysis 2 Chapter (II) Background Research Area 3 (I). History of Sitpinquin Village 3 (2). Geographical Selling 4 (3). Communication and Transportation 4 (4). Population 5 (5). Pattern ofHousing 6 (6). Operational Definition 6 Chapter (tIl) Education 8 (1). Local Perception on Education 8 (2). -

Burma's Prisons and Labour Camps

P.O Box 93, Mae Sot, Tak Province 63110, Thailand e.mail: [email protected] website: www.aappb.org ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Burma’s Prisons and Labour Camps: Silent Killing Fields Summary 250 In October 2008, reports emerged from Burma that the 200 military junta had ordered its courts to expedite the trials of 150 political activists. Since then, Sentenced 100 357 activists have been handed Transferred down harsh punishments, 50 including sentences of up to 104 years.1 Shortly after sentencing, 0 the regime began to systematically transfer political prisoners to prisons all around Burma, far from their families. This has a serious detrimental impact on both their physical and mental health. Medical supplies in prisons are wholly inadequate, and often only obtained through bribes to prison officials. It is left to the families to provide medicines, but prison transfers make it very difficult for them to visit their loved ones in jail. Prison transfers are also another form of psychological torture by the regime, aimed at both the prisoners and their families. Since November 2008, at least 228 political prisoners have been transferred to jails away from their families.2 The long-term consequences for the health of political prisoners recently transferred will be very serious. 1 AAPP, 30 April 2009. 2 AAPP, 30 April 2009. 1 At least 127 political prisoners are currently in poor health. At least 19 of them are in urgent need of proper medical treatment. Political prisoners’ right to healthcare is systematically denied by the regime. Burma’s healthcare system in prisons is completely inadequate, especially in jails in remote areas. -

B COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 194/2008 of 25

2008R0194 — EN — 23.12.2009 — 004.001 — 1 This document is meant purely as a documentation tool and the institutions do not assume any liability for its contents ►B COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 194/2008 of 25 February 2008 renewing and strengthening the restrictive measures in respect of Burma/Myanmar and repealing Regulation (EC) No 817/2006 (OJ L 66, 10.3.2008, p. 1) Amended by: Official Journal No page date ►M1 Commission Regulation (EC) No 385/2008 of 29 April 2008 L 116 5 30.4.2008 ►M2 Commission Regulation (EC) No 353/2009 of 28 April 2009 L 108 20 29.4.2009 ►M3 Commission Regulation (EC) No 747/2009 of 14 August 2009 L 212 10 15.8.2009 ►M4 Commission Regulation (EU) No 1267/2009 of 18 December 2009 L 339 24 22.12.2009 Corrected by: ►C1 Corrigendum, OJ L 198, 26.7.2008, p. 74 (385/2008) 2008R0194 — EN — 23.12.2009 — 004.001 — 2 ▼B COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 194/2008 of 25 February 2008 renewing and strengthening the restrictive measures in respect of Burma/Myanmar and repealing Regulation (EC) No 817/2006 THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Community, and in particular Articles 60 and 301 thereof, Having regard to Common Position 2007/750/CFSP of 19 November 2007 amending Common Position 2006/318/CFSP renewing restrictive measures against Burma/Myanmar (1), Having regard to the proposal from the Commission, Whereas: (1) On 28 October 1996, the Council, concerned at the absence of progress towards democratisation and at the continuing violation of human rights in Burma/Myanmar, imposed certain restrictive measures against Burma/Myanmar by Common Position 1996/635/CFSP (2). -

MYANMAR: Why the U.S

SUPPORTING HUMAN RIGHTS IN MYANMAR: Why the U.S. Should Maintain Existing Sanctions Authority MAY 2016 SUPPORTING HUMAN RIGHTS IN MYANMAR 1 COVER PHOTO: Kachin Independence Army soldiers on patrol, Kachin State © Ryan Roco 2013 Fortify Rights works to ensure and defend human rights for all. We investigate human rights abuses, engage stakeholders, and strengthen initiatives led by human rights defenders, affected communities, and civil society. We believe in the effectiveness of evidence-based research, the power of strategic truth telling, and the importance of working in close collaboration with individuals, communities, and movements. Fortify Rights is an independent, nonprofit organization based in Southeast Asia and registered in the United States and Switzerland. www.fortifyrights.org United to End Genocide is the largest activist organization in America dedicated to preventing and ending genocide and mass atrocities worldwide. The United to End Genocide community includes faith leaders, students, artists, investors and genocide survivors, and all those who believe we must fulfill the promise the world made following the Holocaust-“Never Again!” www.endgenocide.org SUPPORTING HUMAN RIGHTS IN MYANMAR: Why the U.S. Should Maintain Existing Sanctions Authority MAY 2016 SUPPORTING HUMAN RIGHTS IN MYANMAR 4 CONTENTS SUMMARY................................................................................................................................ 1 METHODOLOGY .....................................................................................................................5 -

Field Survey and Collection of Traditionally Grown Crops in Northern Areas of Myanmar, 2006

〔植探報 Vol. 23 : 161 ~ 175,2007〕 ミャンマー北部における伝統的作物の調査と収集(2006年) 渡邉 和男 1)・YE TINT TUN 2)・河瀨 眞琴 3) 1) 筑波大学大学院・生命環境科学研究科 2) ミャンマー農業灌漑省・ミャンマー農業公社 3) 農業生物資源研究所・ジーンバンク Field Survey and Collection of Traditionally Grown Crops in Northern Areas of Myanmar, 2006 Kazuo WATANABE1), Ye Tint Tun2) and Makoto KAWASE3) 1) Graduate School of Life and Environment Sciences, Tsukuba University, 1-1-1 Tennodai, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-8572, Japan 2) Myanma Rice Research Institute, Myanma Agriculture Service, Hmowbi, Yangon, Myanmar, 3) Genebank, National Institute of Agrobiological Sciences, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-8602, Japan Summary Myanmar has been suggested to harbor genetic diversity of wild and cultivated rice and several other cultivated plants. Systematic field survey and collection of plant genetic resources were, however, not so intensively organized there. A limited number of explorations were organized by IRRI in early 1990s, by JICA Seedbank Project during 1997 to 2002, and by NIAS Genebank Project from 1999 to 2005. A field exploration was planned and carried out to investigate and collect genetic variation of upland rice, small millets, pulses, ginger and turmeric in Kachin State in cooperation of scientists of Tsukuba University (Japan), National Institute of Agrobiological Sciences (Japan) and the Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation (Myanmar) from November 14 to December 1, 2006. This field research was funded by a Grand-in-Aid for Overseas Scientific Research of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan. Even though our botanical trip was not so smoothly carried out as planned mainly due to severe road conditions caused by unexpected weather, we successfully surveyed a wide range of areas in Kachin State, and collected 90 samples of plant genetic resources. -

Additional Agenda Item, Report of the Officers of the Governing Bodypdf

International Labour Conference Provisional Record 2-2 101st Session, Geneva, May–June 2012 Additional agenda item Report of the Officers of the Governing Body 1. At its 313th Session (March 2012), the Governing Body requested its Officers to undertake a mission (the “Mission”) to Myanmar and to report to the International Labour Conference at its 101st Session (2012) on all relevant issues, with a view to assisting the Conference’s consideration of a review of the measures previously adopted by the Conference 1 to secure compliance by Myanmar with the recommendations of the Commission of Inquiry that had been established to examine the observance by Myanmar of its obligation in respect of the Forced Labour Convention, 1930 (No. 29). 2. The Mission, composed of Mr Greg Vines, Chairperson of the Governing Body, Mr Luc Cortebeeck, Worker Vice-Chairperson of the Governing Body, and Mr Brent Wilton, Secretary of the Employers’ group of the Governing Body, as the personal representative of Mr Daniel Funes de Rioja, the Employer Vice-Chairperson of the Governing Body, visited Myanmar from 1 to 5 May 2012. The Mission met with authorities at the highest level, including: the President of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar; the Speaker of the Parliament’s lower house; the Minister of Labour; the Minister of Foreign Affairs; the Attorney-General; other representatives of the Government; and the Commander-in-Chief of the Defence Services. It was also able to meet and discuss with Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, President of the National League for Democracy (NLD); representatives of other opposition political parties; the National Human Rights Commission; labour activists; the leaders of newly registered workers’ organizations; and employers’ representatives from the Union of Myanmar Federation of Chambers of Commerce and Industry (UMFCCI) and recently registered employers’ organizations. -

A Comparison of the First and Fiftieth Year of Burmese Law Reports

385 A COMPARISON OF THE FIRST AND FIFTIETH YEAR OF INDEPENDENT BURMA'S LAW REPORTS By Myint Zan* This article compares the annual Law Reports of the first year of Burmese independence in 1948 with those published in the fiftieth year of Burmese independence (1998). In making the comparison, the author highlights the fundamental changes that occurred in the structure and composition of the highest courts in Burma, along with relevant background and factors effecting these changes. There was a movement away from the predominant use of English in 1948 towards judgments exclusively in Burmese in the 1998 Law Reports. Burma's neighbours, who shared a common law legal heritage, did not follow this trend after their independence. This shift, combined with Burma's isolation from the rest of the world, makes analysis of Burmese case law from the past three and a half decades very difficult for anyone not proficient in the Burmese language. This article tries to fill the lacunae as far as the Law Report from the fiftieth year of Burma's independence is concerned. Cet article propose une comparaison des recueils de jurisprudence publiés annuellement sur une période d'un demi-siècle, à compter de la première année de l'indépendance birmane en 1948, jusqu'au cinquantième anniversaire de son indépendance en 1998. A la faveur de cette comparaison, l'auteur souligne les changements fondamentaux qui ont affecté la structure et composition des cours birmanes mais s'intéresse aussi au contexte dans lesquels ces changements ont été effectués. Il souligne ainsi que le mouvement contre l'usage de l'anglais dans les recueils des décisions de justice des cours birmanes, amorcé après 1948, a trouvé son point d'aboutissement en 1998, date à laquelle seule la langue birmane est utilisée. -

Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar

Myanmar Development Research (MDR) (Present) Enlightened Myanmar Research (EMR) Wing (3), Room (A-305) Thitsar Garden Housing. 3 Street , 8 Quarter. South Okkalarpa Township. Yangon, Myanmar +951 562439 Acknowledgement of Myanmar Development Research This edition of the “Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010-2012)” is the first published collection of facts and information of political parties which legally registered at the Union Election Commission since the pre-election period of Myanmar’s milestone 2010 election and the post-election period of the 2012 by-elections. This publication is also an important milestone for Myanmar Development Research (MDR) as it is the organization’s first project that was conducted directly in response to the needs of civil society and different stakeholders who have been putting efforts in the process of the political transition of Myanmar towards a peaceful and developed democratic society. We would like to thank our supporters who made this project possible and those who worked hard from the beginning to the end of publication and launching ceremony. In particular: (1) Heinrich B�ll Stiftung (Southeast Asia) for their support of the project and for providing funding to publish “Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010-2012)”. (2) Party leaders, the elected MPs, record keepers of the 56 parties in this book who lent their valuable time to contribute to the project, given the limited time frame and other challenges such as technical and communication problems. (3) The Chairperson of the Union Election Commission and all the members of the Commission for their advice and contributions. -

Myanmar Update February 2016 Report

STATUS OF HUMAN RIGHTS & SANCTIONS IN MYANMAR FEBRUARY 2016 REPORT Summary. This report reviews the February 2016 developments relating to human rights in Myanmar. Relatedly, it addresses the interchange between Myanmar’s reform efforts and the responses of the international community. I. Political Developments......................................................................................................2 A. Election-Related Developments and Power Transition...............................................2 B. Constitutional Reform....................................................................................................3 C. International and Community Sanctions......................................................................4 II. Civil and Political Rights...................................................................................................4 A. Press and Media Laws/Restrictions...............................................................................4 B. Official Corruption.........................................................................................................5 III. Political Prisoners..............................................................................................................5 IV. Governance and Rule of Law...........................................................................................6 V. Economic Development.....................................................................................................7 A. Land Seizures..................................................................................................................7 -

Myanmar Amnesty International Submission to the UN Universal Periodic Review Tenth Session of the UPR Working Group, January 2011

Myanmar Amnesty International submission to the UN Universal Periodic Review Tenth session of the UPR Working Group, January 2011 B. Normative and institutional framework of the State The administration of justice in Myanmar is marked by the absence of an independent judiciary and the criminalization of peaceful political dissent. The provisions of the 2008 Constitution and many laws do not meet international human rights standards. Myanmar has only ratified two international human rights treaties, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women and the Convention of the Rights of the Child; however, the provisions of these are not adequately reflected in domestic law. The Constitution The new Constitution was adopted in a referendum held in the immediate aftermath of Cyclone Nargis in May 2008. It will come into force after national elections slated to take place towards the end of 2010. Amnesty International has serious concerns in relation to a number of elements within the Constitution that undermine international human rights standards and enable impunity for perpetrators of human rights violations, including past violations: • There are no provisions explicitly prohibiting torture and other ill‐treatment. There are similarly no provisions guaranteeing the rights of arrested persons to be informed promptly of the nature and cause of any charges against them or to a fair and public hearing, and the right of those arrested to be brought before a court within 24 hours does not extend to “matters on precautionary measures” taken on security and similar grounds. Provisions on freedom of expression, association and assembly are restricted by vague references to “community peace and tranquillity” (Article 354).