A Comparison of the First and Fiftieth Year of Burmese Law Reports

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

B COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 194/2008 of 25

2008R0194 — EN — 23.12.2009 — 004.001 — 1 This document is meant purely as a documentation tool and the institutions do not assume any liability for its contents ►B COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 194/2008 of 25 February 2008 renewing and strengthening the restrictive measures in respect of Burma/Myanmar and repealing Regulation (EC) No 817/2006 (OJ L 66, 10.3.2008, p. 1) Amended by: Official Journal No page date ►M1 Commission Regulation (EC) No 385/2008 of 29 April 2008 L 116 5 30.4.2008 ►M2 Commission Regulation (EC) No 353/2009 of 28 April 2009 L 108 20 29.4.2009 ►M3 Commission Regulation (EC) No 747/2009 of 14 August 2009 L 212 10 15.8.2009 ►M4 Commission Regulation (EU) No 1267/2009 of 18 December 2009 L 339 24 22.12.2009 Corrected by: ►C1 Corrigendum, OJ L 198, 26.7.2008, p. 74 (385/2008) 2008R0194 — EN — 23.12.2009 — 004.001 — 2 ▼B COUNCIL REGULATION (EC) No 194/2008 of 25 February 2008 renewing and strengthening the restrictive measures in respect of Burma/Myanmar and repealing Regulation (EC) No 817/2006 THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Community, and in particular Articles 60 and 301 thereof, Having regard to Common Position 2007/750/CFSP of 19 November 2007 amending Common Position 2006/318/CFSP renewing restrictive measures against Burma/Myanmar (1), Having regard to the proposal from the Commission, Whereas: (1) On 28 October 1996, the Council, concerned at the absence of progress towards democratisation and at the continuing violation of human rights in Burma/Myanmar, imposed certain restrictive measures against Burma/Myanmar by Common Position 1996/635/CFSP (2). -

Additional Agenda Item, Report of the Officers of the Governing Bodypdf

International Labour Conference Provisional Record 2-2 101st Session, Geneva, May–June 2012 Additional agenda item Report of the Officers of the Governing Body 1. At its 313th Session (March 2012), the Governing Body requested its Officers to undertake a mission (the “Mission”) to Myanmar and to report to the International Labour Conference at its 101st Session (2012) on all relevant issues, with a view to assisting the Conference’s consideration of a review of the measures previously adopted by the Conference 1 to secure compliance by Myanmar with the recommendations of the Commission of Inquiry that had been established to examine the observance by Myanmar of its obligation in respect of the Forced Labour Convention, 1930 (No. 29). 2. The Mission, composed of Mr Greg Vines, Chairperson of the Governing Body, Mr Luc Cortebeeck, Worker Vice-Chairperson of the Governing Body, and Mr Brent Wilton, Secretary of the Employers’ group of the Governing Body, as the personal representative of Mr Daniel Funes de Rioja, the Employer Vice-Chairperson of the Governing Body, visited Myanmar from 1 to 5 May 2012. The Mission met with authorities at the highest level, including: the President of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar; the Speaker of the Parliament’s lower house; the Minister of Labour; the Minister of Foreign Affairs; the Attorney-General; other representatives of the Government; and the Commander-in-Chief of the Defence Services. It was also able to meet and discuss with Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, President of the National League for Democracy (NLD); representatives of other opposition political parties; the National Human Rights Commission; labour activists; the leaders of newly registered workers’ organizations; and employers’ representatives from the Union of Myanmar Federation of Chambers of Commerce and Industry (UMFCCI) and recently registered employers’ organizations. -

Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar

Myanmar Development Research (MDR) (Present) Enlightened Myanmar Research (EMR) Wing (3), Room (A-305) Thitsar Garden Housing. 3 Street , 8 Quarter. South Okkalarpa Township. Yangon, Myanmar +951 562439 Acknowledgement of Myanmar Development Research This edition of the “Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010-2012)” is the first published collection of facts and information of political parties which legally registered at the Union Election Commission since the pre-election period of Myanmar’s milestone 2010 election and the post-election period of the 2012 by-elections. This publication is also an important milestone for Myanmar Development Research (MDR) as it is the organization’s first project that was conducted directly in response to the needs of civil society and different stakeholders who have been putting efforts in the process of the political transition of Myanmar towards a peaceful and developed democratic society. We would like to thank our supporters who made this project possible and those who worked hard from the beginning to the end of publication and launching ceremony. In particular: (1) Heinrich B�ll Stiftung (Southeast Asia) for their support of the project and for providing funding to publish “Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010-2012)”. (2) Party leaders, the elected MPs, record keepers of the 56 parties in this book who lent their valuable time to contribute to the project, given the limited time frame and other challenges such as technical and communication problems. (3) The Chairperson of the Union Election Commission and all the members of the Commission for their advice and contributions. -

Placement Test for the 2019 English Language Training for Government Officials

Placement Test for The 2019 English Language Training for Government Officials The 2019 English Language Training for Government Officials, in cooperation between the Union Civil Service Board, New Zealand Embassy (Yangon), and Victoria University in Wellington; will be conducted at the Office No. 17, the Union Civil Service Board (UCSB), Nay Pyi Taw. Placement Test for this training programme will be held from 10:00am to 10:35 am on 16 November 2018 (Friday). As registration will be started at 09:00 am, all candidates are requested to arrive by not later than 09:15am for your registration. Subsequently, sharing session of exam information will be commenced at 09:40 am for your kind attention. As the applicants are aware, the list of applicants are divided into three (3) different groups (Senior Level, Middle Level, and Staff Officer Level). For your ease to find the role numbers, the UCSB would like to use such terms “S” “ M” and “SO” respectively, “ S” herein referred to the Senior Level, “M” used for middle level, and SO referred to Staff Officer Level. -2- Union Civil Service Board Nomination Lists to attend English Language Training for Government Officials Group (1) Director Level and Above Level and Same Salary Functionaries Roll No. Name Designation Ministry/Organization Remark S- 1 U Aung Kyaw Zaw Director President’s Office S- 2 U Thein Win Director President’s Office S- 3 U Bhone Kyi Aung Deputy Director The Pyidaungsu Hluttaw General S- 4 U Zaw Oo Director The Pyithu Hluttaw S- 5 U Zaw Min Aung Director The Supreme Court of -

Commission Regulation (EC)

L 108/20 EN Official Journal of the European Union 29.4.2009 COMMISSION REGULATION (EC) No 353/2009 of 28 April 2009 amending Council Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 renewing and strengthening the restrictive measures in respect of Burma/Myanmar THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, (3) Common Position 2009/351/CFSP of 27 April 2009 ( 2 ) amends Annexes II and III to Common Position 2006/318/CFSP of 27 April 2006. Annexes VI and VII Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European to Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 should, therefore, be Community, amended accordingly. Having regard to Council Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 of (4) In order to ensure that the measures provided for in this 25 February 2008 renewing and strengthening the restrictive Regulation are effective, this Regulation should enter into measures in respect of Burma/Myanmar and repealing Regu- force immediately, lation (EC) No 817/2006 ( 1), and in particular Article 18(1)(b) thereof, HAS ADOPTED THIS REGULATION: Whereas: Article 1 1. Annex VI to Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 is hereby (1) Annex VI to Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 lists the replaced by the text of Annex I to this Regulation. persons, groups and entities covered by the freezing of funds and economic resources under that Regulation. 2. Annex VII to Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 is hereby replaced by the text of Annex II to this Regulation. (2) Annex VII to Regulation (EC) No 194/2008 lists enter- prises owned or controlled by the Government of Article 2 Burma/Myanmar or its members or persons associated with them, subject to restrictions on investment under This Regulation shall enter into force on the day of its publi- that Regulation. -

Myanmar (Burma): a Reading Guide Andrew Selth

Griffith Asia Institute Research Paper Myanmar (Burma): A reading guide Andrew Selth i About the Griffith Asia Institute The Griffith Asia Institute (GAI) is an internationally recognised research centre in the Griffith Business School. We reflect Griffith University’s longstanding commitment and future aspirations for the study of and engagement with nations of Asia and the Pacific. At GAI, our vision is to be the informed voice leading Australia’s strategic engagement in the Asia Pacific— cultivating the knowledge, capabilities and connections that will inform and enrich Australia’s Asia-Pacific future. We do this by: i) conducting and supporting excellent and relevant research on the politics, security, economies and development of the Asia-Pacific region; ii) facilitating high level dialogues and partnerships for policy impact in the region; iii) leading and informing public debate on Australia’s place in the Asia Pacific; and iv) shaping the next generation of Asia-Pacific leaders through positive learning experiences in the region. The Griffith Asia Institute’s ‘Research Papers’ publish the institute’s policy-relevant research on Australia and its regional environment. The texts of published papers and the titles of upcoming publications can be found on the Institute’s website: www.griffith.edu.au/asia-institute ‘Myanmar (Burma): A reading guide’ February 2021 ii About the Author Andrew Selth Andrew Selth is an Adjunct Professor at the Griffith Asia Institute, Griffith University. He has been studying international security issues and Asian affairs for 45 years, as a diplomat, strategic intelligence analyst and research scholar. Between 1974 and 1986 he was assigned to the Australian missions in Rangoon, Seoul and Wellington, and later held senior positions in both the Defence Intelligence Organisation and Office of National Assessments. -

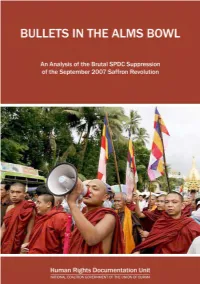

Bullets in the Alms Bowl

BULLETS IN THE ALMS BOWL An Analysis of the Brutal SPDC Suppression of the September 2007 Saffron Revolution March 2008 This report is dedicated to the memory of all those who lost their lives for their part in the September 2007 pro-democracy protests in the struggle for justice and democracy in Burma. May that memory not fade May your death not be in vain May our voices never be silenced Bullets in the Alms Bowl An Analysis of the Brutal SPDC Suppression of the September 2007 Saffron Revolution Written, edited and published by the Human Rights Documentation Unit March 2008 © Copyright March 2008 by the Human Rights Documentation Unit The Human Rights Documentation Unit (HRDU) is indebted to all those who had the courage to not only participate in the September protests, but also to share their stories with us and in doing so made this report possible. The HRDU would like to thank those individuals and organizations who provided us with information and helped to confirm many of the reports that we received. Though we cannot mention many of you by name, we are grateful for your support. The HRDU would also like to thank the Irish Government who funded the publication of this report through its Department of Foreign Affairs. Front Cover: A procession of Buddhist monks marching through downtown Rangoon on 27 September 2007. Despite the peaceful nature of the demonstrations, the SPDC cracked down on protestors with disproportionate lethal force [© EPA]. Rear Cover (clockwise from top): An assembly of Buddhist monks stage a peaceful protest before a police barricade near Shwedagon Pagoda in Rangoon on 26 September 2007 [© Reuters]; Security personnel stepped up security at key locations around Rangoon on 28 September 2007 in preparation for further protests [© Reuters]; A Buddhist monk holding a placard which carried the message on the minds of all protestors, Sangha and civilian alike. -

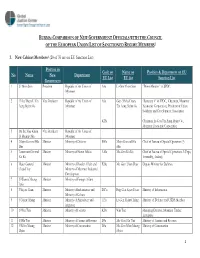

28 of 35 Are on EU Sanction List)

BURMA: COMPARISON OF NEW GOVERNMENT OFFICIALS WITH THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION LIST OF SANCTIONED REGIME MEMBERS1 1. New Cabinet Members2 (28 of 35 are on EU Sanction List) Position in Code on Name on Position & Department on EU No Name New Department EU List EU list Sanction List Government 1 U Thein Sein President Republic of the Union of A4a Lt-Gen Thein Sein “Prime Minister” of SPDC Myanmar 2 Thiha Thura U Tin Vice President Republic of the Union of A5a Gen (Thiha Thura) “Secretary 1” of SPDC, Chairman, Myanmar Aung Myint Oo Myanmar Tin Aung Myint Oo Economic Corporation, President of Union Solidarity and Development Association K23a Chairman, Lt-Gen Tin Aung Myint Oo, Myanmar Economic Corporation 3 Dr. Sai Mao Kham Vice President Republic of the Union of @ Maung Ohn Myanmar 4 Major General Hla Minister Ministry of Defense B10a Major General Hla Chief of Bureau of Special Operation (3) Min Min 5 Lieutenant General Minister Ministry of Home Affairs A10a Maj-Gen Ko Ko Chief of Bureau of Special Operations 3 (Pegu, Ko Ko Irrawaddy, Arakan). 6 Major General Minister Ministry of Border Affairs and E28a Maj-Gen Thein Htay Deputy Minister for Defence Thein Htay Ministry of Myanmar Industrial Development 7 U Wunna Maung Minister Ministry of Foreign Affairs Lwin 8 U Kyaw Hsan Minister Ministry of Information and D17a Brig-Gen Kyaw Hsan Ministry of Information Ministry of Culture 9 U Myint Hlaing Minister Ministry of Agriculture and 115a Lt-Gen Myint Hlaing Ministry of Defence and USDA Member Irrigation 10 U Win Tun Minister Ministry -

QUARTERLY PROGRESS REPORT July to September 2017

NATIONAL COMMUNITY DRIVEN DEVELOPMENT PROJECT Project No: H814-MM and IDA Credit no: 56870 QUARTERLY PROGRESS REPORT July to September 2017 Submitted in compliance with Section II A of the Financing Agreement between the Republic of the Union of Myanmar and the International Development Association Presented by: National Community Driven Development Secretariat Department of Rural Development Draft 18 October 2017 NCDDP Quarterly Progress Report (July – Sept 2017) List of Abbreviations and Acronyms BER - Bid Evaluation Report BG - Block Grant BGA - Block Grant Agreement CFA - Community Force Account CDD - Community-driven Development DRD - Department of Rural Development DSW - Department of Social Welfare ECOPs - Environmental Codes of Practice EMP - Environmental Management Plan EOI - Expression of Interest (procurement document) ESMF - Environmental and Social Management Framework GESI - Gender Empowerment and Social Inclusion GWG - Gender Working Group MEB - Myanmar Economic Bank NOL - No-Objection Letter (WB document) OM - Operation Manual PSC - Performance Security Guarantee PMIS - Project Management Information System RFP - Request for Proposals RFQ - Request for Quotations TOF - Training of Facilitators TTF - Training of Technical Facilitators TOT - Training of Trainers TS - Township TTA - Township Technical Assistance UTA - Union Level Technical Assistance VL - Village Leader VTDSC - Village Tract Development Support Committee VPSC - Village Project Support Committee VTDP - Village Tract Development Plan VTPSC - Village Tract -

Recent Arrests List

ARRESTS No. Name Sex Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and S: 8 of the Export and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Import Law and S: 25 Superintendent Kyi 1 (Daw) Aung San Suu Kyi F State Counsellor (Chairman of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw chief ministers and ministers in the states and of the Natural Disaster Lin of Special Branch regions were also detained. Management law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and S: 25 of the Natural President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Superintendent Myint 2 (U) Win Myint M President (Vice Chairman-1 of NLD) 1-Feb-21 Disaster Management House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw chief ministers and ministers in the states and Naing law regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s 3 (U) Henry Van Thio M Vice President 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw chief ministers and ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Speaker of the Amyotha Hluttaw, the President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s 4 (U) Mann Win Khaing Than M upper house of the Myanmar 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Nay Pyi Taw chief ministers and ministers in the states and parliament regions were also detained. -

Chronology of Political Prisoners in Burma for October 2008 • • • • • • • • • • • • Summary of Current Situation

Chronology of Political Prisoners in Burma for October 2008 • • • • • • • • • • • • Summary of Current Situation There are a total of 2,147 political prisoners in Burma. These include: Category Number Monks 217 Members of Parliament 17 Students 265 Women 180 NLD members 468 Members of the Human Rights Defenders and 35 Promoters network Ethnic nationalities 211 Cyclone Nargis volunteers 22 Teachers 22 Media activists 41 Lawyers 12 In poor health 107 Since the protests in August, leading to last September’s Saffron Revolution, a total of 1,022 activists have been arrested. Monthly Trend Analysis In October, there were 18 arrests, 45 activists were sentenced and 20 were released. In comparison with September, there were fewer arrests (18 compared to 88 in September), but many more activists have been sentenced (45 compared to 18 in September). September marked the anniversary of last year’s Saffron Revolution, and the regime cracked down on activists engaged in activities to mark the anniversary, which accounts for the high number of arrests last month. This month has seen a push by the regime to bring legal proceedings against political activists to a swift conclusion, in a series of grossly unfair trials. Unfair Trials Trials of political prisoners have been taking place in closed sessions, with family members denied permission to attend. Trials of high profile prisoners like 88 Generation Group leaders Min Ko Naing and monk leaders have been held in Insein Prison special court, presided over by judges from various Rangoon District courts. Defence lawyers have been given insufficient time to prepare their cases. In some instances defence lawyers were prevented from presenting their case in court altogether. -

Burma (Myanmar)

report Burma (Myanmar): The Time for Change By Martin Smith Acknowledgements Minority Rights Group International Minority Rights Group International (MRG) gratefully acknowl- Minority Rights Group International (MRG) is a non-govern- edges the support of all organizations and individuals who mental organization (NGO) working to secure the rights of gave financial and other assistance for this report ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities and indigenous peo- ples worldwide, and to promote cooperation and The Author understanding between communities. Our activities are Martin Smith is a writer and journalist specializing in Burmese focused on international advocacy, training, publishing and and ethnic minority affairs. He is author of Burma: Insurgency outreach. We are guided by the needs expressed by our and the Politics of Ethnicity, and he has reported for a variety worldwide partner network of organizations which represent of media, including the Guardian and the BBC. His television minority and indigenous peoples. work includes the documentaries, Dying for Democracy (UK Channel Four) and Forty Million Hostages (BBC). He has also MRG works with over 130 organizations in nearly 60 coun- written papers and reports for a number of academic institu- tries. Our governing Council, which meets twice a year, has tions and non-governmental organizations, including Article members from 10 different countries. MRG has consultative 19, World University Service, Tokyo University of Foreign Stud- status with the United Nations Economic and Social Council ies and Anti-Slavery International. Other publications include (ECOSOC), and is registered as a charity and a company Ethnic Groups in Burma: Development, Democracy and limited by guarantee under English law.