MYANMAR: Why the U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crimes in Burma

Crimes in Burma A Report By Table of Contents Preface iii Executive Summary 1 Methodology 5 I. History of Burma 7 A. Early History and Independence in 1948 7 B. Military Rule: 1962-1988 9 C. The 1988 Popular Uprising and Democratic Elections in 1990 11 D. Military Rule Since 1988 12 II. International Criminal Law Framework 21 A. Crimes Against Humanity: Chapeau or Common Elements 24 B. War Crimes: Chapeau or Common Elements 27 C. Enumerated or Prohibited Acts 30 III. Human Rights Violations in Burma 37 A. Forced Displacement 39 B. Sexual Violence 51 C. Extrajudicial Killings and Torture 64 D. Legal Evaluation 74 ii Preface IV. Precedents for Action 77 A. The Security Council’s Chapter VII Powers 78 B. The Former Yugoslavia 80 C. Rwanda 82 D. Darfur 84 E. Burma 86 Conclusion 91 Appendix 93 Acknowledgments 103 Preface For many years, the world has watched with horror as the human rights nightmare in Burma has unfolded under military rule. The struggle for democracy of Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and other political prisoners since 1988 has captured the imagination of people around the world. The strength of Buddhist monks and their Saffron Revolution in 2007 brought Burma to the international community’s attention yet again. But a lesser known story—one just as appalling in terms of human rights—has been occurring in Burma over the past decade and a half: epidemic levels of forced labor in the 1990s, the recruitment of tens of thousands of child soldiers, widespread sexual violence, extrajudicial killings and torture, and more than a million displaced persons. -

Q&A on Elections in BURMA

Q&A ON ELECTIONS IN BURMA PHOTOGRapHS BY PLATON Q&A ON ELECTIONS IN BuRma INTRODUCTION PHOTOGRapHS BY PLATON Burma will hold multi-party elections on November 7, 2010, the first in 20 years. Some contend the elections could spark a gradual process of democratization and the opening of civil society space in Burma. Human Rights Watch believes that the elections must be seen in the context of the Burmese military government’s carefully manufactured electoral process over many years that is designed to ensure continued military rule, albeit with a civilian façade. The generals’ “Road Map to Disciplined Democracy” has been a path filled with human rights violations: the brutal crackdown on peaceful protesters in 2007, the doubling of the number of political prisoners in Burma since then to more than 2000, the marginalization of WIN MIN, CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER ethnic minority communities in border areas, a rewritten constitution that A medical student at the time, Win undermines rights and guarantees continued military rule, and carefully Min became a leader of the 1988 constructed electoral laws that subtly bar the main opposition candidates. pro-democracy demonstrations in Burma. After years fighting in the jungle, Win Min has become one of the This political repression takes place in an environment that already sharply restricts most articulate intellectuals in exile. freedom of association, assembly, and expression. Burma’s media is tightly controlled Educated at Harvard University, he is by the authorities, and many media outlets trying to report on the elections have been now one of the driving forces behind an innovative collective called the Vahu (in reduced to reporting on official announcements’ and interviews with party leaders: no Burmese: Plural) Development Institute, public opinion or opposition is permitted. -

SUPPORTING the MOVEMENT for a FREE and DEMOCRATIC BURMA 2002-2012 “We Have Been Knocking on This Door for a Long Time and It’S Never Opened

THE STORY OF OUR IMPACT SUPPORTING THE MOVEMENT FOR A FREE AND DEMOCRATIC BURMA 2002-2012 “We have been knocking on this door for a long time and it’s never opened. Now we are knocking and it’s opened a little. We are ready to struggle and push it until it opens further.” — Karen Human Rights Group, an AJWS grantee working on human rights in Burma “If you stand together, your voice will be heard.” —Women’s human rights activist and AJWS grantee, Burma ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This case study was written by Elyse Lightman Samuels, in collaboration with AJWS’s staff working on Burma, and with editing support from Leah Kaplan Robins. It was designed by Davyd Pittman and Elizabeth Leih. We would like to thank our courageous grantees cited in this case study, who provided valuable input on the history of the civil and political rights movement in Burma and key feedback on drafts. Without them, this story would not be possible. PUBLISHED JULY 2012 COVER Monks, nuns and other citizens march in a peaceful demonstration during the Saffron Revolution. PHOTO BETH JONES Table of Contents Introduction 2 Background: Mounting Terror and Early Attempts at Opposition 3 Documenting and Voicing Shared Problems Leads to Results 3 Women are Empowered to Take the Lead 4 Underground Communications Efforts Support the Saffron Revolution 5 A Disaster Spawns Further Growth of the Grassroots Movement 6 Women Insist that Burma’s Crimes be Investigated 6 Citizens Demand Fair Elections and a Constitution that Ensures Equality for All 6 The Door to Human Rights Begins to Open 7 Civil Society Plays a Role in Peace Negotiations 8 Volunteers Help Build Sustainable Organizations 8 Looking Ahead 8 INTRODUCTION The story of Burma is one of the most profound examples of progress in global justice that AJWS has ever seen. -

FIDH Report Half Empty: Burma's Political Parties and Their Human Rights Commitments

Half Empty: Burma’s political parties and their human rights commitments November 2015 / N°668a November © AFP PHOTO / Soe Than Win MPs attend parliamentary session in Naypyidaw on July 4, 2012. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Foreword 4 2. Executive summary 4 3. Methodology 5 4. Outgoing Parliament disappoints on human rights 7 11 5.1 - Media freedom 12 5.2 - Religious discrimination 12 5.3 - Role of the military 13 5.4 - Accountability for past crimes 13 5.5 - Legislative reform 14 5.6 - Women’s rights 14 5.7 - Death penalty 14 5.8 - Ethnic minority rights 15 15 5.10 - Human rights defenders 15 5.11 - Investment, development, and infrastructure projects 16 5.12 - Next government’s top priorities 16 6. Recommendations to elected MPs 17 7. Appendixes 20 7.1 - Appendix 1: Survey’s complete results 20 7.2 - Appendix 2: Political parties contesting the 8 November election 25 1. FOREWORD By Tomás Ojea Quintana, former UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar to visit the new Parliament in Myanmar, I was able to economic course. 2. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Suu Kyi, is expected to win. 1 Burma Issues & Concerns Vol. 6: The generals’ election, January 2011 4 FIDH - HALF EMPTY: BURMA’S POLITICAL PARTIES AND THEIR HUMAN RIGHTS COMMITMENTS concerns. The report provides numerous recommendations to MPs, based on statements and reports issued by various UN special procedures as well as resolutions adopted by 3. METHODOLOGY [See Appendix 2: Political parties contesting the 8 November election Appendix 1: Survey’s complete results FIDH - HALF EMPTY: BURMA’S POLITICAL PARTIES AND THEIR HUMAN RIGHTS COMMITMENTS 5 6 FIDH - HALF EMPTY: BURMA’S POLITICAL PARTIES AND THEIR HUMAN RIGHTS COMMITMENTS 4. -

Report of Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar

A/HRC/39/64 Advance Edited Version Distr.: General 12 September 2018 Original: English Human Rights Council Thirty-ninth session 10–28 September 2018 Agenda item 4 Human rights situations that require the Council’s attention Report of the independent international fact-finding mission on Myanmar* Summary The Human Rights Council established the independent international fact-finding mission on Myanmar in its resolution 34/22. In accordance with its mandate, the mission focused on the situation in Kachin, Rakhine and Shan States since 2011. It also examined the infringement of fundamental freedoms, including the rights to freedom of expression, assembly and peaceful association, and the question of hate speech. The mission established consistent patterns of serious human rights violations and abuses in Kachin, Rakhine and Shan States, in addition to serious violations of international humanitarian law. These are principally committed by the Myanmar security forces, particularly the military. Their operations are based on policies, tactics and conduct that consistently fail to respect international law, including by deliberately targeting civilians. Many violations amount to the gravest crimes under international law. In the light of the pervasive culture of impunity at the domestic level, the mission finds that the impetus for accountability must come from the international community. It makes concrete recommendations to that end, including that named senior generals of the Myanmar military should be investigated and prosecuted in an international criminal tribunal for genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes. * The present report was submitted after the deadline in order to reflect the most recent developments. A/HRC/39/64 Contents Page I. -

Shadow Report Prepared by GEN for CEDAW and It Has Partnered with the Global Justice Center for the Information Gathering and Preparation of This Report

ABOUT GLOBAL JUSTICE CENTER The Global Justice Center is a US-based human rights organization with consultative status to the United Nations that works to achieve sustainable justice, peace and security by building a global rule of law based on gender equality and universally enforced international human rights laws. ABOUT GENDER EQUALITY NETWORK Gender Equality Network (GEN) is a Myanmar-based diverse and inclusive network of more than a hundred civil society organizations, national and international NGOs and Technical Resource Persons, working to bring about gender equality and the fulfillment of women's rights in Myanmar. This is the first shadow report prepared by GEN for CEDAW and it has partnered with the Global Justice Center for the information gathering and preparation of this report. GEN brings solid in- country expertise and experience to the table, and as an in-country lobbying force it has worked closely on all the issues highlighted in this report. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS GEN would like to acknowledge the time and effort put into the preparation of this report by the CEDAW NGO Report Working Group, drawn from the GEN membership. The Working Group met several times over the course of March-May 2016 to ensure the shadow report reflects all the concerns raised by the members of the GEN and the most pressing factors hindering the advancement of women’s rights in Myanmar. (Please see Annex 1 for a list of all contributors.) TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary .................................................................................................................. -

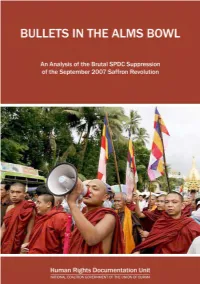

Bullets in the Alms Bowl

BULLETS IN THE ALMS BOWL An Analysis of the Brutal SPDC Suppression of the September 2007 Saffron Revolution March 2008 This report is dedicated to the memory of all those who lost their lives for their part in the September 2007 pro-democracy protests in the struggle for justice and democracy in Burma. May that memory not fade May your death not be in vain May our voices never be silenced Bullets in the Alms Bowl An Analysis of the Brutal SPDC Suppression of the September 2007 Saffron Revolution Written, edited and published by the Human Rights Documentation Unit March 2008 © Copyright March 2008 by the Human Rights Documentation Unit The Human Rights Documentation Unit (HRDU) is indebted to all those who had the courage to not only participate in the September protests, but also to share their stories with us and in doing so made this report possible. The HRDU would like to thank those individuals and organizations who provided us with information and helped to confirm many of the reports that we received. Though we cannot mention many of you by name, we are grateful for your support. The HRDU would also like to thank the Irish Government who funded the publication of this report through its Department of Foreign Affairs. Front Cover: A procession of Buddhist monks marching through downtown Rangoon on 27 September 2007. Despite the peaceful nature of the demonstrations, the SPDC cracked down on protestors with disproportionate lethal force [© EPA]. Rear Cover (clockwise from top): An assembly of Buddhist monks stage a peaceful protest before a police barricade near Shwedagon Pagoda in Rangoon on 26 September 2007 [© Reuters]; Security personnel stepped up security at key locations around Rangoon on 28 September 2007 in preparation for further protests [© Reuters]; A Buddhist monk holding a placard which carried the message on the minds of all protestors, Sangha and civilian alike. -

Myanmar: UN Human Rights Council Must Urge Newly-Elected Government to Prioritise Legal Reform to Guarantee the Right to Freedom of Expression

Myanmar: UN Human Rights Council must urge newly-elected government to prioritise legal reform to guarantee the right to freedom of expression 23 December 2020 ARTICLE 19 Free Word Centre 60 Farringdon Road London, EC1R 3GA United Kingdom T: +44 20 7324 2500 F: +44 20 7490 0566 E: [email protected] W: www.article19.org Tw: @article19org Fb: facebook.com/article19org © ARTICLE 19, 2020 This work is provided under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-ShareAlike 2.5 licence. You are free to copy, distribute and display this work and to make derivative works, provided you: 1) give credit to ARTICLE 19; 2) do not use this work for commercial purposes; 3) distribute any works derived from this publication under a licence identical to this one. To access the full legal text of this licence, please visit: http://creativecommons. org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/legalcode. ARTICLE 19 would appreciate receiving a copy of any materials in which information from this report is used. Introduction 2 CONTENTS Introduction 4 Prosecution of journalists, human rights defenders, and others exercising the right to freedom of expression and peaceful assembly 4 Digital rights 6 Suppression of expression during the 2020 elections 8 Hate speech 10 Introduction 3 INTRODUCTION One year after the Human Rights Council (‘the Council’) adopted Resolution 43/261 on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, the government’s efforts to suppress dissent continue unabated. In the past year, despite the Council’s recommendation that Myanmar repeal or amend laws that criminalise expression, Myanmar authorities have continued to prosecute journalists, human rights defenders and others who speak critically of the government or military. -

1 February 2020 Myanmar: UN Human Rights Council Must Act To

February 2020 Myanmar: UN Human Rights Council must act to secure key reforms ahead of 2020 elections In the year since the Human Rights Council (the Council) adopted Resolution 40/291 on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, the space for political discourse and participation in the country has continued to shrink. Ahead of national elections widely expected to be held in November 2020, Myanmar authorities must facilitate the full political participation of all sectors of society, ensuring that individuals may freely express their opinions, even when they are controversial or critical of the government, military or other vested interests. In the past year, Myanmar authorities have continued to violate the rights to freedom of expression, information, peaceful assembly and association while cracking down on online and offline speech. Under the guise of tackling ‘hate speech,’ Myanmar authorities have expedited efforts to pass so-called ‘anti- hatred’ legislation, which risks aggravating discrimination against religious and ethnic minority groups. Authorities have yet to take meaningful steps to promote the rights of religious or ethnic minorities within the country and to guarantee their full political participation. The ongoing internet shutdown in Rakhine State – affecting nine townships and now entering its ninth month – is one of the longest ever recorded and an egregious violation of the rights to freedom of expression and information. It disproportionately affects some of Myanmar’s most vulnerable minorities and hinders the reporting of human rights violations in an active conflict zone. The government has arbitrarily applied restrictive legislation to stifle criticism of political leaders and military authorities. -

Human Rights Council the Economic Interests of the Myanmar Military

A/HRC/42/CRP.3 5 August 2019 English only Human Rights Council Forty-second session 9–27 September 2019 Agenda item 4 Human Rights situations that require the Council’s attention The economic interests of the Myanmar military Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on Myanmar An earlier version of this repot, released on 5 August 2019, misindentified details related to a number of companies and individuals. They have been corrected in this version of the report, and are outlined in “Update from the UN Independent International Fact- Finding Mission on Myanmar on its report on “The economic interests of Myanmar’s military”, available on the Mission’s website at https://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/MyanmarFFM/Pages/EconomicInterestsMyanmarMilitary.aspx GE. A/HRC/42/CRP.3 Contents Page I. Executive summary and key recommendations ............................................................................... 3 II. Mandate, methodology, international legal and policy framework .................................................. 6 A. Mandate ................................................................................................................................... 6 B. Methodology ............................................................................................................................ 7 C. International legal and policy framework ................................................................................ 8 III. Mapping Tatmadaw economic structures and interests ................................................................... -

Human Rights in Myanmar: Ethnic Cleansing

36th session of the UN Human Rights Council Human Rights in Myanmar: Ethnic Cleansing Friday 15 September 2017 15h00 – 16h30 Room XXVII, Palais des Nations, Geneva Concept Note The situation in Myanmar is alarmingly deteriorating. Myanmar government is repeatedly condemned for grave breaches of international human rights law and international humanitarian law. However, mass atrocities against Rohingya Muslim minority in Rakhine State continue to these days and seriously worsened within the last month. The government fails to ensure the halt of violence and protection from abuse against ethnic minorities, particularly Rohingya religious minority. The incitement to discrimination and violence based on national, racial and religious hatred is widespread and systematic. Within the general context of anti-Muslim rhetoric, the security forces have implemented persecution policies for decades. Ethnic minorities are targeted within the so-called “Burmanization” policy and the most shocking is the case of Rohingya. For centuries the Rohingya community of approximately 1.3 million members mostly live in Rakhine State with historical roots in Myanmar dating back to ancient times. Nevertheless, the government refuses to give them the nationality and instead it uses the term “Bengali” to refer to Rohingya as foreigners. Over 100,000 ethnic minority Rohingya have taken a perilous journey to leave the country by sea; the Rohingya are fleeing horrific Apartheid-like conditions where 140,000 are confined in what many describe as "concentration camps".1 It is estimated some 350,000 Rohingya have fled Myanmar in search of protection in Bangladesh, including an estimated 74,000 who arrived in late 2016 as a result of a security crackdown in northern Rakhine State.2 According to UNHCR, in less than three weeks over 270,000 people have fled to Bangladesh, three times more than the 87,000 who fled the previous operation. -

Structural Barriers to Accountability for Human Rights Abuses in Burma

FACT SHEET | OCTOBER 2018 Structural Barriers To Accountability For Human Rights Abuses In Burma Recent reports detailing the heinous human rights abuses committed in Rakhine State in Burma have triggered calls for perpetrators to be held accountable, both domestically and internationally. The Office of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court (“ICC”) has opened a preliminary examination1 and the UN Human Rights Council has established an investigative mechanism to collect, preserve, and analyze evidence of crimes.2 International action is not only justified but absolutely necessary given the impossibility of holding perpetrators to account using domestic justice mechanisms. Decades of unchecked human rights abuses against ethnic groups in other areas of Burma and deeply-entrenched domestic structural barriers preventing accountability have emboldened the military and contributed to the current crisis. Without international action to address and tackle Burma’s culture of impunity and the structural barriers that underpin them, this pattern will likely continue unabated. This Fact Sheet details the domestic structural barriers that impede accountability for perpetrators and preclude justice for victims of human rights abuses in Burma. These obstacles, formalized with the “adoption” by a spurious referendum of a new Constitution of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar (the “Constitution”) in 2008, prevent any full accounting for human rights violations committed by the military (the “Tatmadaw” or “Defense Forces”) in Burma. Obstacles