Myanmar's Armed Forces and the Rohingya Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crimes in Burma

Crimes in Burma A Report By Table of Contents Preface iii Executive Summary 1 Methodology 5 I. History of Burma 7 A. Early History and Independence in 1948 7 B. Military Rule: 1962-1988 9 C. The 1988 Popular Uprising and Democratic Elections in 1990 11 D. Military Rule Since 1988 12 II. International Criminal Law Framework 21 A. Crimes Against Humanity: Chapeau or Common Elements 24 B. War Crimes: Chapeau or Common Elements 27 C. Enumerated or Prohibited Acts 30 III. Human Rights Violations in Burma 37 A. Forced Displacement 39 B. Sexual Violence 51 C. Extrajudicial Killings and Torture 64 D. Legal Evaluation 74 ii Preface IV. Precedents for Action 77 A. The Security Council’s Chapter VII Powers 78 B. The Former Yugoslavia 80 C. Rwanda 82 D. Darfur 84 E. Burma 86 Conclusion 91 Appendix 93 Acknowledgments 103 Preface For many years, the world has watched with horror as the human rights nightmare in Burma has unfolded under military rule. The struggle for democracy of Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and other political prisoners since 1988 has captured the imagination of people around the world. The strength of Buddhist monks and their Saffron Revolution in 2007 brought Burma to the international community’s attention yet again. But a lesser known story—one just as appalling in terms of human rights—has been occurring in Burma over the past decade and a half: epidemic levels of forced labor in the 1990s, the recruitment of tens of thousands of child soldiers, widespread sexual violence, extrajudicial killings and torture, and more than a million displaced persons. -

Karen-Burmese Refugees

Karen-Burmese Refugees An orientation for health workers and volunteers Developed by Christine Dziedzic, Student Project Officer Community Nutrition Unit, Annerley Road Community Health Background Information • The Karen-Burmese live in mountainous jungle regions of Myanmar (southern and eastern), and Thailand • Myanmar is located in South- East Asia – Formally known as Burma – Developing and largely rural – Bordered by China, Tibet, Laos, Thailand, Bangladesh and India Source: cyberschoolbus.un.org Community Nutrition Unit, Annerley Road Community Health P: (07) 3010 3550 Myanmar - Background InformationWorld Health Organisation (2006) • Population: 50 519 000 • Life expectancy at birth: – 61 years • Infant mortality rate – Per 1000 live births: 106 – 4.7 / 1000 in Australia (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2006) • Language: Burmese – Indigenous peoples have their own languages Flag of Myanmar – Over 126 dialects Source: cyberschoolbus.un.org Community Nutrition Unit, Annerley Road Community Health P: (07) 3010 3550 History of Myanmar • 1886: Became a province of British India • 1948: Gained independence • 1962: Military dictatorship took power – Large outflow of refugees • 1988: Martial law declared – Increased refugee numbers • State of civil war for much of the past 50 years Community Nutrition Unit, Annerley Road Community Health P: (07) 3010 3550 Ethnic Groups • Major ethnic group: Burmese • Largest indigenous population: Karen • Other indigenous races include: – Shans – Chins – Mon – Rakhine – Katchin • Ethnic tension -

Rohingya – the Name and Its Living Archive Jacques Leider

Rohingya – the Name and its Living Archive Jacques Leider To cite this version: Jacques Leider. Rohingya – the Name and its Living Archive. 2018. hal-02325206 HAL Id: hal-02325206 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02325206 Submitted on 25 Oct 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Spotlight: The Rakhine Issue Rohingya – the Name and its Living Archive Jacques P. Leider deconstructs the living history of the name “Rohingya.” he intriguingly opposing trends about using, not to do research on the history of the Rohingya and the name Tusing or rejecting the name “Rohingya” illustrate itself. Rohingyas and pro-Rohingya activists were keen to a captivating history of the naming and self-identifying prove that the Union of Burma had already recognised the of Arakan’s Muslim community. Today, “Rohingya” is Rohingya as an ethnic group in the 1950s and 1960s so that globally accepted as the name for most Muslims in North their citizenship rights could not be denied. Academics and Rakhine. But authorities and most people in Myanmar still independent researchers also formed archives containing use the term “Bengalis” in referring to the self-identifying official and non-official documents that allowed a close Rohingyas, linking them to Bangladesh and Burma’s own examination of the chronological record. -

Dr. Jacques P. Leider (Bangkok; Yangon) Muslimische Gemeinschaften Im Buddhistischen Myanmar Die Rohingyafrage. Vom Ethno-Kultur

Gastvorträge zu Religion und Politik in Myanmar / Südostasien Dr. Jacques P. Leider (Bangkok; Yangon) Montag, 25.Juni, 16-18 Uhr. Ort: Hüfferstrasse 27, 3.Obergeschoss, Raum B.3.06 Muslimische Gemeinschaften im buddhistischen Myanmar Der Vortrag bietet einen historischen Überblick über die Bildung muslimischer Gemeinschaften von der Zeit der buddhistischen Königreiche über die Kolonialzeit bis in die Zeit des unabhängigen Birmas (Myanmar). Das Wiedererstarken eines buddhistischen Nationalismus der birmanischen Bevölke-rungsmehrheit ist Hintergund islamophober Gewaltexzesse im Zuge der politischen Öffnung seit 2011. Der historische Rückblick versucht die Aktualität in die gesellschaftlichen Zusammenhänge und die zeitgenössiche Geschichte des Landes einzuordnen. Dienstag, 26.Juni, 10-12 Uhr. Ort: Johannisstr. 8-10, KTh V Die Rohingyafrage. Vom ethno-kulturellen Konflikt zum Vorwurf des staatlichen Genozids Die Rohingyas stellen die grösste muslimische Bevölkerungsgruppe in Myanmar. Die Hälfte der Muslime die die Rohingyaidentität in Anspruch nimmt, lebt aber, teils seit Jahrzehnten, ausserhalb des Landes. Ihre langjährige Unterdrückung, ihre politische Verfolgung und ihre massive Vertreibung haben die humanitären und legalen Aspekte der Rohingyafrage insbesondere seit Mitte 2017 ins Zen-trum des globalen Interesses an Myanmar gerückt. Der Vortrag wird insbesondere die widersprüch-lichen myanmarischen und internationalen Positionen zur Rohingyafrage besprechen. © Sai Lin Aung Htet Dr. Jacques P. Leider ist Historiker und Südostasienforscher der Ecole française d’Extrême-Orient und lebt in Bangkok und Yangon. Der Schwerpunkt seiner wissenschaftlichen Arbeit liegt im Bereich der frühmodernen und kolonialen Geschichte der Königreiche Arakans (Rakhine State) und Birmas (Myanmar). Im Rahmen des ethno-religiösen Konflikts in Rakhine State hat er sich verstärkt mit dem Hintergrund der Identitätsbildung der muslimischen Rohingya im Grenzgebiet zu Bangladesh beschäftigt. -

Q&A on Elections in BURMA

Q&A ON ELECTIONS IN BURMA PHOTOGRapHS BY PLATON Q&A ON ELECTIONS IN BuRma INTRODUCTION PHOTOGRapHS BY PLATON Burma will hold multi-party elections on November 7, 2010, the first in 20 years. Some contend the elections could spark a gradual process of democratization and the opening of civil society space in Burma. Human Rights Watch believes that the elections must be seen in the context of the Burmese military government’s carefully manufactured electoral process over many years that is designed to ensure continued military rule, albeit with a civilian façade. The generals’ “Road Map to Disciplined Democracy” has been a path filled with human rights violations: the brutal crackdown on peaceful protesters in 2007, the doubling of the number of political prisoners in Burma since then to more than 2000, the marginalization of WIN MIN, CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER ethnic minority communities in border areas, a rewritten constitution that A medical student at the time, Win undermines rights and guarantees continued military rule, and carefully Min became a leader of the 1988 constructed electoral laws that subtly bar the main opposition candidates. pro-democracy demonstrations in Burma. After years fighting in the jungle, Win Min has become one of the This political repression takes place in an environment that already sharply restricts most articulate intellectuals in exile. freedom of association, assembly, and expression. Burma’s media is tightly controlled Educated at Harvard University, he is by the authorities, and many media outlets trying to report on the elections have been now one of the driving forces behind an innovative collective called the Vahu (in reduced to reporting on official announcements’ and interviews with party leaders: no Burmese: Plural) Development Institute, public opinion or opposition is permitted. -

Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Import Law Dekkhina and President U Win Myint Were and S: 25 of the District Detained

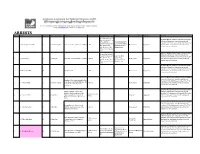

Current No. Name Sex /Age Father's Name Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Address Remark Condition Superintendent Myanmar Military Seizes Power Kyi Lin of and Senior NLD leaders S: 8 of the Export Special Branch, including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Import Law Dekkhina and President U Win Myint were and S: 25 of the District detained. The NLD’s chief Natural Disaster Administrator ministers and ministers in the Management law, (S: 8 and 67), states and regions were also 1 (Daw) Aung San Suu Kyi F General Aung San State Counsellor (Chairman of NLD) 1-Feb-21 Penal Code - Superintendent House Arrest Naypyitaw detained. 505(B), S: 67 of Myint Naing Arrested State Counselor Aung the (S: 25), U Soe San Suu Kyi has been charged in Telecommunicatio Soe Shwe (S: Rangoon on March 25 under ns Law, Official 505 –b), Section 3 of the Official Secrets Secret Act S:3 Superintendent Act. Aung Myo Lwin (S: 3) Myanmar Military Seizes Power S: 25 of the and Senior NLD leaders Natural Disaster including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi Superintendent Management law, and President U Win Myint were Myint Naing, Penal Code - detained. The NLD’s chief 2 (U) Win Myint M U Tun Kyin President (Vice Chairman-1 of NLD) 1-Feb-21 Dekkhina House Arrest Naypyitaw 505(B), S: 67 of ministers and ministers in the District the states and regions were also Administrator Telecommunicatio detained. ns Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. -

Senate TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 18, 2018

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 115 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 164 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 18, 2018 No. 155 House of Representatives The House was not in session today. Its next meeting will be held on Thursday, September 20, 2018, at 9:30 a.m. Senate TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 18, 2018 The Senate met at 10 a.m. and was U.S. SENATE, until they leaked it to the press on the called to order by the Honorable CINDY PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE, eve of the scheduled committee vote. Washington, DC, September 18, 2018. HYDE-SMITH, a Senator from the State But as my colleague, the senior Sen- of Mississippi. To the Senate. ator from Texas, said yesterday, the f Under the provisions of rule I, para- graph 3, of the Standing Rules of the blatant malpractice demonstrated by PRAYER Senate, I hereby appoint the Honorable our colleagues across the aisle will not The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- CINDY HYDE-SMITH, a Senator from the stop the Senate from moving forward fered the following prayer: State of Mississippi, to perform the du- in a responsible manner. Let us pray. ties of the Chair. As I said yesterday, I have full con- Eternal God, whose mercy is great ORRIN G. HATCH, unto the Heavens, help us to do what is President pro tempore. fidence in Chairman GRASSLEY to lead right. May we not forget that You are Mrs. HYDE-SMITH thereupon as- the committee through the sensitive the judge of the Earth and that we are sumed the Chair as Acting President and highly irregular situation in which accountable to You. -

The Sentinel Period Ending 27 Oct 2018

The Sentinel Human Rights Action :: Humanitarian Response :: Health :: Education :: Heritage Stewardship :: Sustainable Development __________________________________________________ Period ending 27 October 2018 This weekly digest is intended to aggregate and distill key content from a broad spectrum of practice domains and organization types including key agencies/IGOs, NGOs, governments, academic and research institutions, consortiums and collaborations, foundations, and commercial organizations. We also monitor a spectrum of peer- reviewed journals and general media channels. The Sentinel’s geographic scope is global/regional but selected country-level content is included. We recognize that this spectrum/scope yields an indicative and not an exhaustive product. The Sentinel is a service of the Center for Governance, Evidence, Ethics, Policy & Practice, a program of the GE2P2 Global Foundation, which is solely responsible for its content. Comments and suggestions should be directed to: David R. Curry Editor, The Sentinel President. GE2P2 Global Foundation [email protected] The Sentinel is also available as a pdf document linked from this page: http://ge2p2-center.net/ Support this knowledge-sharing service: Your financial support helps us cover our costs and address a current shortfall in our annual operating budget. Click here to donate and thank you in advance for your contribution. _____________________________________________ Contents [click on link below to move to associated content] :: Week in Review :: Key Agency/IGO/Governments Watch - Selected Updates from 30+ entities :: INGO/Consortia/Joint Initiatives Watch - Media Releases, Major Initiatives, Research :: Foundation/Major Donor Watch -Selected Updates :: Journal Watch - Key articles and abstracts from 100+ peer-reviewed journals :: Week in Review A highly selective capture of strategic developments, research, commentary, analysis and announcements spanning Human Rights Action, Humanitarian Response, Health, Education, Holistic Development, Heritage Stewardship, Sustainable Resilience. -

Myanmar Buddhism of the Pagan Period

MYANMAR BUDDHISM OF THE PAGAN PERIOD (AD 1000-1300) BY WIN THAN TUN (MA, Mandalay University) A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SOUTHEAST ASIAN STUDIES PROGRAMME NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE 2002 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to the people who have contributed to the successful completion of this thesis. First of all, I wish to express my gratitude to the National University of Singapore which offered me a 3-year scholarship for this study. I wish to express my indebtedness to Professor Than Tun. Although I have never been his student, I was taught with his book on Old Myanmar (Khet-hoà: Mranmâ Râjawaà), and I learnt a lot from my discussions with him; and, therefore, I regard him as one of my teachers. I am also greatly indebted to my Sayas Dr. Myo Myint and Professor Han Tint, and friends U Ni Tut, U Yaw Han Tun and U Soe Kyaw Thu of Mandalay University for helping me with the sources I needed. I also owe my gratitude to U Win Maung (Tampavatî) (who let me use his collection of photos and negatives), U Zin Moe (who assisted me in making a raw map of Pagan), Bob Hudson (who provided me with some unpublished data on the monuments of Pagan), and David Kyle Latinis for his kind suggestions on writing my early chapters. I’m greatly indebted to Cho Cho (Centre for Advanced Studies in Architecture, NUS) for providing me with some of the drawings: figures 2, 22, 25, 26 and 38. -

Total Detention, Charge and Fatality Lists

ARRESTS No. Name Sex /Age Father's Name Position Date of Arrest Section of Law Plaintiff Current Condition Address Remark S: 8 of the Export and Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD Import Law and S: 25 leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and of the Natural Superintendent Kyi President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s Disaster Management Lin of Special Branch, 1 (Daw) Aung San Suu Kyi F General Aung San State Counsellor (Chairman of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and law, Penal Code - Dekkhina District regions were also detained. 505(B), S: 67 of the Administrator Telecommunications Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD S: 25 of the Natural leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Disaster Management Superintendent President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s law, Penal Code - Myint Naing, 2 (U) Win Myint M U Tun Kyin President (Vice Chairman-1 of NLD) 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and 505(B), S: 67 of the Dekkhina District regions were also detained. Telecommunications Administrator Law Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and President U Win Myint were detained. The NLD’s 3 (U) Henry Van Thio M Vice President 1-Feb-21 House Arrest Naypyitaw chief ministers and ministers in the states and regions were also detained. Myanmar Military Seizes Power and Senior NLD leaders including Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and Speaker of the Union Assembly, the President U Win Myint were detained. -

Frontier Capitalism and Politics of Dispossession in Myanmar: the Case of the Mwetaung (Gullu Mual) Nickel Mine in Chin State Einzenberger, Rainer

www.ssoar.info Frontier Capitalism and Politics of Dispossession in Myanmar: the Case of the Mwetaung (Gullu Mual) Nickel Mine in Chin State Einzenberger, Rainer Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Einzenberger, R. (2018). Frontier Capitalism and Politics of Dispossession in Myanmar: the Case of the Mwetaung (Gullu Mual) Nickel Mine in Chin State. ASEAS - Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies, 11(1), 13-34. https:// doi.org/10.14764/10.ASEAS-2018.1-2 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY-NC-ND Lizenz This document is made available under a CC BY-NC-ND Licence (Namensnennung-Nicht-kommerziell-Keine Bearbeitung) zur (Attribution-Non Comercial-NoDerivatives). For more Information Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu den CC-Lizenzen finden see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/deed.de Aktuelle Südostasienforschung Current Research on Southeast Asia Frontier Capitalism and Politics of Dispossession in Myanmar: The Case of the Mwetaung (Gullu Mual) Nickel Mine in Chin State Rainer Einzenberger ► Einzenberger, R. (2018). Frontier capitalism and politics of dispossession in Myanmar: The case of the Mwetaung (Gullu Mual) nickel mine in Chin State. Austrian Journal of South-East Asian Studies, 11(1), 13-34. Since 2010, Myanmar has experienced unprecedented political and economic changes described in the literature as democratic transition or metamorphosis. The aim of this paper is to analyze the strategy of accumulation by dispossession in the frontier areas as a precondition and persistent element of Myanmar’s transition. -

Siti Umayatun, S.Hum. TESIS

PERAN KOREA MUSLIM FEDERATION (KMF) DALAM PERTUMBUHAN ISLAM DI KOREA SELATAN TAHUN 1967-2015 M Disusun Oleh : Siti Umayatun, S.Hum. NIM : 1520510121 TESIS Diajukan Kepada Pascasarjana UIN Sunan Kalijaga Untuk Memenuhi Salah Satu Syarat Guna Memperoleh Gelar Master of Arts (M. A) Program Studi Interdisciplinary Islamic Studies (IIS) Konsentrasi Sejarah KebudayaanIslam YOGYAKARTA 2017 ABSTRAK Pada era Modern, bersamaan dengan Perang Korea tahun 1950-1953 M benih ajaran agama Islam mulai tumbuh di semenanjung Korea Selatan melalui kontak hubungan dengan pasukan perdamaian Turki. Dakwah bil hal tentara Turki selama terjadi perang melahirkan beberapa Muallaf generasi pertama Muslim Korea. Jumlah mereka pertahunnya meningkat sehingga terbentuk perkumpulan Muslim Korea dan tahun 1967 M menjadi organisasi Korea Muslim Federation (KMF) yang statusnya diakui oleh pemerintah Korea bahkan diberi surat izin mendirikan bangunan. Semua Muslim yang diorganisir KMF awalnya benar-benar bagian integral dari bangsa Korea yang menjadi Muallaf bukan karena kedatangan imigran Muslim dari negara-negara Islam. Sejak tahun 1970-an pemerintah Korea membantu KMF dalam perkembangan Islam, padahal selama itu mereka simpati pada Zionis dan pro Israel bahkan sejak masa kemerdekaan sampai sekarang berada di bawah naungan Amerika. Pemerintah Korea memperlakukan Muslim atas dasar sama dengan kelompok agama lainnya, tidak mendiskriminasi bahkan membuka pintu lebar-lebar dakwah KMF dengan memberikan sebidang tanah untuk pembangunan masjid dan universitas Islam. Meski Islam agama baru dan minoritas di Korea namun memiliki posisi terhormat dan stategis. Dalam memobilisasi perkembangan Islam, KMF melakukan kaderisasi mengirim beberapa pemuda Muslim Korea ke negara- negara Muslim untuk belajar Islam dan melakukan riset. Terlihat bahwa minoritas Muslim Korea punya nasip lebih cerah dan menjanjikan jika dibandingkan dengan keadaan minoritas Muslim lainnya.