1 February 2020 Myanmar: UN Human Rights Council Must Act To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

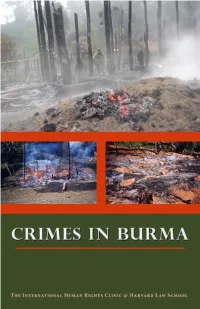

Crimes in Burma

Crimes in Burma A Report By Table of Contents Preface iii Executive Summary 1 Methodology 5 I. History of Burma 7 A. Early History and Independence in 1948 7 B. Military Rule: 1962-1988 9 C. The 1988 Popular Uprising and Democratic Elections in 1990 11 D. Military Rule Since 1988 12 II. International Criminal Law Framework 21 A. Crimes Against Humanity: Chapeau or Common Elements 24 B. War Crimes: Chapeau or Common Elements 27 C. Enumerated or Prohibited Acts 30 III. Human Rights Violations in Burma 37 A. Forced Displacement 39 B. Sexual Violence 51 C. Extrajudicial Killings and Torture 64 D. Legal Evaluation 74 ii Preface IV. Precedents for Action 77 A. The Security Council’s Chapter VII Powers 78 B. The Former Yugoslavia 80 C. Rwanda 82 D. Darfur 84 E. Burma 86 Conclusion 91 Appendix 93 Acknowledgments 103 Preface For many years, the world has watched with horror as the human rights nightmare in Burma has unfolded under military rule. The struggle for democracy of Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and other political prisoners since 1988 has captured the imagination of people around the world. The strength of Buddhist monks and their Saffron Revolution in 2007 brought Burma to the international community’s attention yet again. But a lesser known story—one just as appalling in terms of human rights—has been occurring in Burma over the past decade and a half: epidemic levels of forced labor in the 1990s, the recruitment of tens of thousands of child soldiers, widespread sexual violence, extrajudicial killings and torture, and more than a million displaced persons. -

Q&A on Elections in BURMA

Q&A ON ELECTIONS IN BURMA PHOTOGRapHS BY PLATON Q&A ON ELECTIONS IN BuRma INTRODUCTION PHOTOGRapHS BY PLATON Burma will hold multi-party elections on November 7, 2010, the first in 20 years. Some contend the elections could spark a gradual process of democratization and the opening of civil society space in Burma. Human Rights Watch believes that the elections must be seen in the context of the Burmese military government’s carefully manufactured electoral process over many years that is designed to ensure continued military rule, albeit with a civilian façade. The generals’ “Road Map to Disciplined Democracy” has been a path filled with human rights violations: the brutal crackdown on peaceful protesters in 2007, the doubling of the number of political prisoners in Burma since then to more than 2000, the marginalization of WIN MIN, CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER ethnic minority communities in border areas, a rewritten constitution that A medical student at the time, Win undermines rights and guarantees continued military rule, and carefully Min became a leader of the 1988 constructed electoral laws that subtly bar the main opposition candidates. pro-democracy demonstrations in Burma. After years fighting in the jungle, Win Min has become one of the This political repression takes place in an environment that already sharply restricts most articulate intellectuals in exile. freedom of association, assembly, and expression. Burma’s media is tightly controlled Educated at Harvard University, he is by the authorities, and many media outlets trying to report on the elections have been now one of the driving forces behind an innovative collective called the Vahu (in reduced to reporting on official announcements’ and interviews with party leaders: no Burmese: Plural) Development Institute, public opinion or opposition is permitted. -

Minorities Under Threat, Diversity in Danger: Patterns of Systemic Discrimination in Southeast Myanmar

Minorities under Threat, Diversity in Danger: Patterns of Systemic Discrimination in Southeast Myanmar Karen Human Rights Group November 2020 Minorities under Threat, Diversity in Danger: Patterns of Systemic Discrimination in Southeast Myanmar Written and published by the Karen Human Rights Group KHRG #2020-02, November 2020 For front and back cover photo captions, please refer to the final page of this report. The Karen Human Rights Group (KHRG) was founded in 1992 and documents the situation of villagers and townspeople in rural southeast Myanmar through their direct testimonies, supported by photographic and other evidence. KHRG operates independently and is not affiliated with any political or other organisation. Examples of our work can be seen online at www.khrg.org. Printed copies of our reports may be obtained subject to approval and availability by sending a request to [email protected]. This report is published by KHRG, © KHRG 2020. All rights reserved. Contents may be reproduced or distributed on a not-for-profit basis or quotes for media and related purposes but reproduction for commercial purposes requires the prior permission of KHRG. The final version of this report was originally written in English and then translated into Burmese. KHRG refers to the English language report as the authoritative version. This report is not for commercial sale. The printing of this report is supported by: DISCLAIMER The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of Karen Human Rights Group and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of HARP Facility. Contents Introduction .................................................................................................... 4 Methodology .................................................................................................. 7 Abbreviations................................................................................................. 9 Map: KHRG’s operation area ..................................................................... -

January Chronology 2016

JANUARY CHRONOLOGY 2016 Summary of the CurreNt SituatioN: There are 86 political prisoNers incarcerated in Burma. 399 actiVists are curreNtly awaitiNg trial for political actioNs. Picture from IrraWaddy © 2016 Accessed JaNuary 28, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS MONTH IN REVIEW ............................................................................................................................................................ 1 DETENTIONS ......................................................................................................................................................................... 2 SENTENCES ........................................................................................................................................................................... 3 RELEASES ............................................................................................................................................................................... 4 CONDITIONS OF DETENTIONS ..................................................................................................................................... 5 DEMONSTRATIONS & RESTRICTIONS ON POLITICAL & CIVIL LIBERTIES .............................................. 7 LAND ISSUES ......................................................................................................................................................................... 8 RELATED HUMAN RIGHT NEWS ................................................................................................................................. -

MYANMAR: Why the U.S

SUPPORTING HUMAN RIGHTS IN MYANMAR: Why the U.S. Should Maintain Existing Sanctions Authority MAY 2016 SUPPORTING HUMAN RIGHTS IN MYANMAR 1 COVER PHOTO: Kachin Independence Army soldiers on patrol, Kachin State © Ryan Roco 2013 Fortify Rights works to ensure and defend human rights for all. We investigate human rights abuses, engage stakeholders, and strengthen initiatives led by human rights defenders, affected communities, and civil society. We believe in the effectiveness of evidence-based research, the power of strategic truth telling, and the importance of working in close collaboration with individuals, communities, and movements. Fortify Rights is an independent, nonprofit organization based in Southeast Asia and registered in the United States and Switzerland. www.fortifyrights.org United to End Genocide is the largest activist organization in America dedicated to preventing and ending genocide and mass atrocities worldwide. The United to End Genocide community includes faith leaders, students, artists, investors and genocide survivors, and all those who believe we must fulfill the promise the world made following the Holocaust-“Never Again!” www.endgenocide.org SUPPORTING HUMAN RIGHTS IN MYANMAR: Why the U.S. Should Maintain Existing Sanctions Authority MAY 2016 SUPPORTING HUMAN RIGHTS IN MYANMAR 4 CONTENTS SUMMARY................................................................................................................................ 1 METHODOLOGY .....................................................................................................................5 -

Burma's Political Prisoners and U.S. Sanctions

Burma’s Political Prisoners and U.S. Sanctions Michael F. Martin Specialist in Asian Affairs September 15, 2014 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R42363 c11173008 . Burma’s Political Prisoners and U.S. Sanctions Summary The release of all Burma’s political prisoners is one of the fundamental goals of U.S. policy. Several of the laws imposing sanctions on Burma—including the Burmese Freedom and Democracy Act of 2003 (P.L. 108-61) and the Tom Lantos Block Burmese JADE (Junta’s Anti- Democratic Efforts) Act of 2008 (P.L. 110-286)—require the release of all political prisoners before the sanctions can be terminated. The Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2014 (P.L. 113- 76) requires the Department of State and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) to “support programs for former political prisoners” in Burma, as well as “monitor the number of political prisoners in Burma.” Burma’s President Thein Sein pledged during a July 2013 trip to the United Kingdom to release all “prisoners of conscience” in his country by the end of the year. Since his announcement, he granted amnesties or pardons on seven occasions. While President Thein Sein has asserted that all political prisoners have been freed, several Burmese organizations maintain that dozens of political prisoners remain in jail and that new political prisoners continue to be arrested and sentenced. Hopes for a democratic government and national reconciliation in Burma depend on the release of prisoners, including those associated with the country’s ethnic groups. Several ethnic-based political parties have stated they will not participate in parliamentary elections until their members are released. -

'Going Back to the Old Ways'

‘GOING BACK TO THE OLD WAYS’ A NEW GENERATION OF PRISONERS OF CONSCIENCE IN MYANMAR On 8 November 2015 Myanmar will hold widely anticipated general elections – the first since President Thein Sein and his quasi-civilian government came to power in 2011 after almost five decades of military rule. The elections take place against a backdrop of Under pressure from the international commu- much-touted political, economic, and social re- nity, in 2012 and 2013 President Thein Sein forms, which the government hopes will signal ordered mass prisoner releases which saw to the international community that progress is hundreds of prisoners of conscience freed after being made. years – and in some cases more than a decade – behind bars. These releases prompted cautious “As the election is getting near, most of the optimism that Myanmar was moving towards people who speak out are getting arrested. greater respect for freedom of expression. In I am very concerned. Many activists… are response, the international community began to facing lots of charges. This is a situation relax the pressure, believing that the authorities the government has created – they can pick could and would finally bring about meaningful up anyone they want, when they want.” and long-lasting human rights reforms. Human rights activist from Mandalay, “They [the authorities] have enough July 2015. laws, they can charge anyone with anything. At the same time, they want Yet for many in Myanmar’s vibrant civil society, to pretend that people have rights. But the picture isn’t as rosy as it is often portrayed. as soon as you make problems for them Since the start of 2014, the authorities have or their business they will arrest you.” increasingly stifled peaceful activism and dis- sent – tactics usually associated with the former Min Ko Naing, former prisoner of conscience and military government. -

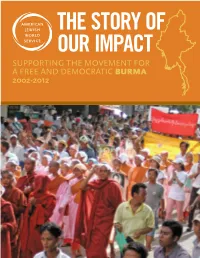

SUPPORTING the MOVEMENT for a FREE and DEMOCRATIC BURMA 2002-2012 “We Have Been Knocking on This Door for a Long Time and It’S Never Opened

THE STORY OF OUR IMPACT SUPPORTING THE MOVEMENT FOR A FREE AND DEMOCRATIC BURMA 2002-2012 “We have been knocking on this door for a long time and it’s never opened. Now we are knocking and it’s opened a little. We are ready to struggle and push it until it opens further.” — Karen Human Rights Group, an AJWS grantee working on human rights in Burma “If you stand together, your voice will be heard.” —Women’s human rights activist and AJWS grantee, Burma ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This case study was written by Elyse Lightman Samuels, in collaboration with AJWS’s staff working on Burma, and with editing support from Leah Kaplan Robins. It was designed by Davyd Pittman and Elizabeth Leih. We would like to thank our courageous grantees cited in this case study, who provided valuable input on the history of the civil and political rights movement in Burma and key feedback on drafts. Without them, this story would not be possible. PUBLISHED JULY 2012 COVER Monks, nuns and other citizens march in a peaceful demonstration during the Saffron Revolution. PHOTO BETH JONES Table of Contents Introduction 2 Background: Mounting Terror and Early Attempts at Opposition 3 Documenting and Voicing Shared Problems Leads to Results 3 Women are Empowered to Take the Lead 4 Underground Communications Efforts Support the Saffron Revolution 5 A Disaster Spawns Further Growth of the Grassroots Movement 6 Women Insist that Burma’s Crimes be Investigated 6 Citizens Demand Fair Elections and a Constitution that Ensures Equality for All 6 The Door to Human Rights Begins to Open 7 Civil Society Plays a Role in Peace Negotiations 8 Volunteers Help Build Sustainable Organizations 8 Looking Ahead 8 INTRODUCTION The story of Burma is one of the most profound examples of progress in global justice that AJWS has ever seen. -

Monthly Chronology of Burma's Political Prisoners for November

P.O Box 93, Mae Sot, Tak Province 63110, Thailand e.mail: [email protected] website: www.aappb.org ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Monthly Chronology of Burma's Political Prisoners for November, 2013 P.O Box 93, Mae Sot, Tak Province 63110, Thailand e.mail: [email protected] website: www.aappb.org SUMMARY OF THE CURRENT SITUATION 66 political prisoners were released on November 15th. This month also saw the sentencing of 30 activists, several of which paid fines rather than face imprisonment. A large number of those imprisoned are farmers sentenced under Section 18 of The Peaceful Assembly Law and Section 505 (b) of The Penal Code. MONTH IN REVIEW The release of 66 political prisoners is welcomed by AAPP (B) and we hope the end of the year will see the release of the remaining detainees. However it is important to remain aware of the high number of political activists who are still facing trial, particularly those who were part of the mass release this month. Individuals such as Naw Ohn Hla and Aung Soe and his colleagues are still facing further charges under various sections of law. It is possible that despite their recent release they will be convicted again very soon. Given the limitations imposed upon them by Section 401 releases, they face lengthy periods in prison under their current charges. A recent interview with Khin Nyunt, the former chief of Burma’s military intelligence unit, reiterates the attitude high ranking officials have taken towards political activists. He stated that “They are looking out for their own interests by saying they were imprisoned without reason. -

FIDH Report Half Empty: Burma's Political Parties and Their Human Rights Commitments

Half Empty: Burma’s political parties and their human rights commitments November 2015 / N°668a November © AFP PHOTO / Soe Than Win MPs attend parliamentary session in Naypyidaw on July 4, 2012. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Foreword 4 2. Executive summary 4 3. Methodology 5 4. Outgoing Parliament disappoints on human rights 7 11 5.1 - Media freedom 12 5.2 - Religious discrimination 12 5.3 - Role of the military 13 5.4 - Accountability for past crimes 13 5.5 - Legislative reform 14 5.6 - Women’s rights 14 5.7 - Death penalty 14 5.8 - Ethnic minority rights 15 15 5.10 - Human rights defenders 15 5.11 - Investment, development, and infrastructure projects 16 5.12 - Next government’s top priorities 16 6. Recommendations to elected MPs 17 7. Appendixes 20 7.1 - Appendix 1: Survey’s complete results 20 7.2 - Appendix 2: Political parties contesting the 8 November election 25 1. FOREWORD By Tomás Ojea Quintana, former UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar to visit the new Parliament in Myanmar, I was able to economic course. 2. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Suu Kyi, is expected to win. 1 Burma Issues & Concerns Vol. 6: The generals’ election, January 2011 4 FIDH - HALF EMPTY: BURMA’S POLITICAL PARTIES AND THEIR HUMAN RIGHTS COMMITMENTS concerns. The report provides numerous recommendations to MPs, based on statements and reports issued by various UN special procedures as well as resolutions adopted by 3. METHODOLOGY [See Appendix 2: Political parties contesting the 8 November election Appendix 1: Survey’s complete results FIDH - HALF EMPTY: BURMA’S POLITICAL PARTIES AND THEIR HUMAN RIGHTS COMMITMENTS 5 6 FIDH - HALF EMPTY: BURMA’S POLITICAL PARTIES AND THEIR HUMAN RIGHTS COMMITMENTS 4. -

A Chance to Fix in Time” Analysis of Freedom of Expression in Four Years Under the Current Government

Athan – Freedom of Expression Activist Organization “A Chance to Fix in Time” Analysis of Freedom of Expression in Four Years Under the Current Government 4 Research Report “A Chance to Fix in Time” Analysis of Freedom of Expression in Four Years Under the Current Government Research Report Athan – Freedom of Expression Activist Organization A Chance to Fix in Time: Analysis of Freedom of Expression in Four Years Under the Current Government Table of Contents Chapters Contents Pages Organisational Background d - Research Methodology 2 - Photo Copyright Chapter (1): Introduction 2 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Overall Analysis of Prosecutions within Four Years 4 Chapter (2): Freedom of Expression 8 2.1 Lawsuits under Telecommunications Law 9 2.2 Lawsuits under the Law Protecting the Privacy and Security 14 of Citizens 2.3 National Record and Archive Law 17 2.4 Lawsuits under Section 505(a), (b) and (c) of the Penal Code 18 2.5 Lawsuits under Section 500 of the Penal Code 23 2.6 Electronic Transactions Law Must Be Repealed 24 2.7 Lawsuits with Sedition Charge under Section 124(a) of the 25 Penal Code 2.8 Lawsuits under Section 295 of the Penal Code 26 2.9 Three Stats Where Free Expression Violated Most 27 Chapter (3): Freedom of Peaceful Assembly and Procession 30 3.1 More Restrictions Included in Drafted Amendment Bill 31 Chapter (4): Media Freedom 34 4.1 News Media Law Lacks of Protection for Media Freedom and 34 Journalistic Rights 4.2 The Tatmadaw’s Filing Lawsuits Against Irrawaddy and 36 Reuters News Agencies a Table of Contents A Chance to -

USAID/BURMA MONTHLY ATMOSPHERIC REPORT October 2019

USAID/BURMA MONTHLY ATMOSPHERIC REPORT October 2019 Contract Number: 72048218C00004 Myanmar Analytical Activity Acknowledgement This report has been written by Kimetrica LLC (www.kimetrica.com) and Bindez Insights (https://bindez.com) as part of the Myanmar Analytical Activity, and is therefore the exclusive property of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Melissa Earl (Kimetrica) is the author of this report and reachable at [email protected] or at Kimetrica LLC, 80 Garden Center, Suite A-368, Broomfield, CO 80020. The author’s views in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. OCTOBER 2019 AT A GLANCE Fighting in Shan and Rakhine States Continues. In Shan State, 20 civilians were injured and 4 killed, and in Rakhine State 25 civilians were injured, at least 8 killed, and thousands displaced. (Pages 2 and 4) Tatmadaw and Kachin Independence Army Conflict Flares Up. For the first time since the Tatmadaw announced its unilateral ceasefire nine months ago, the Tatmadaw and the Kachin Independence Army fought in October. (Page 2) Karen National Liberation Army and Mon National Liberation Army Clash. The Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA) and the Mon National Liberation Army (MNLA) clashed in a territorial dispute this month in Ye Township, Mon State, and Kawkareik Township. (Page 2) Karen Martyr’s Day Organizers Found Guilty. Karen Martyr’s Day Organizers were sentenced to 15 days in prison for not cooperating with authorities under the Peaceful Assembly and Peaceful Procession Law after organizing a peaceful march to commemorate Karen Martyr’s Day in Yangon.