Quid Pro Quo, Knowledge Spillover and Industrial Quality Upgrading

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Development of Pedestrian Protection for the Qoros 3 Sedan

13th International LS-DYNA Users Conference Session: Occupant Safety Development of Pedestrian Protection for the Qoros 3 Sedan Niclas Brannberg, Pere Fonts, Chenhui Huang, Andy Piper, Roger Malkusson Qoros Automotive Co., Ltd. 15/F HSBC Building IFC, No 8. Century Avenue Shanghai 200120, P.R. China Abstract Pedestrian protection has become an important part of the Euro NCAP consumer test and to achieve a 5-star rating for crash safety, a good rating for the different pedestrian load cases is imperative. It was decided at the very start of the Qoros 3 Sedan’s development program that this should be made a priority. A skilled team of safety engineers defined the layout of the vehicle to support this target, and an extensive simulation program using LS-DYNA® was planned to define and validate the design intent without compromising the design of the vehicle as well as maintaining all other important vehicle functions. This paper will provide an insight into part of the journey taken to establish a new vehicle brand in China, fulfilling high European safety standards at an affordable cost, and how Qoros succeeded in this mission with a combination of skills, extensive CAE analysis and finally the validation of the recipe during physical testing. The paper will highlight how the high rating for pedestrian protection was obtained and give a short overview of the complete safety development of the Qoros 3 Sedan. Introduction This paper introduces Qoros and the development of the first vehicle on Qoros’ new compact-segment platform, the Qoros 3 Sedan. It is difficult to present a whole vehicle development in one paper so this text focuses on pedestrian protection as the main topic and will discuss how the rating for pedestrian protection was obtained in the Euro NCAP test as well as discussing some areas where difficulties were encountered with the initial assessment using CAE. -

2017 Passenger Vehicles Actual and Reported Fuel Consumption: a Gap Analysis

2017 Passenger Vehicles Actual and Reported Fuel Consumption: A Gap Analysis Innovation Center for Energy and Transportation December 2017 1 Acknowledgements We wish to thank the Energy Foundation for providing us with the financial support required for the execution of this report and subsequent research work. We would also like to express our sincere thanks for the valuable advice and recommendations provided by distinguished industry experts and colleagues—Jin Yuefu, Li Mengliang, Guo Qianli,. Meng Qingkuo, Ma Dong, Yang Zifei, Xin Yan and Gong Huiming. Authors Lanzhi Qin, Maya Ben Dror, Hongbo Sun, Liping Kang, Feng An Disclosure The report does not represent the views of its funders nor supporters. The Innovation Center for Energy and Transportation (iCET) Beijing Fortune Plaza Tower A Suite 27H No.7 DongSanHuan Middle Rd., Chaoyang District, Beijing 10020 Phone: 0086.10.6585.7324 Email: [email protected] Website: www.icet.org.cn 2 Glossary of Terms LDV Light Duty Vehicles; Vehicles of M1, M2 and N1 category not exceeding 3,500kg curb-weight. Category M1 Vehicles designed and constructed for the carriage of passengers comprising no more than eight seats in addition to the driver's seat. Category M2 Vehicles designed and constructed for the carriage of passengers, comprising more than eight seats in addition to the driver's seat, and having a maximum mass not exceeding 5 tons. Category N1 Vehicles designed and constructed for the carriage of goods and having a maximum mass not exceeding 3.5 tons. Real-world FC FC values calculated based on BearOil app user data input. -

France Toutes Les Voitures Particulières Du Groupe

ANALYSE DE PRESSE DE 14H00 30/08/2018 FRANCE TOUTES LES VOITURES PARTICULIÈRES DU GROUPE PSA HOMOLOGUÉES EN WLTP Toutes les voitures particulières Peugeot, Citroën, DS, Opel et Vauxhall sont aujourd’hui homologués selon le protocole WLTP, plus représentatif de la consommation de carburant en usage réel. Grâce à des choix technologiques judicieux réalisés par anticipation de la réglementation – SCR « Selective Catalytic Reduction » et GPF « Filtre à particules essence », le Groupe PSA est ainsi à l’avant-garde de la mise en œuvre des normes les plus strictes. « Nos choix technologiques pour traiter les émissions polluantes, comme la SCR lancée en 2013 sur tous nos moteurs diesel, et plus récemment le GPF sur les moteurs essence à injection directe, nous permettent de proposer à nos clients des véhicules respectueux de l’environnement et de maintenir notre leadership en matière de réduction des émissions », explique Gilles Le Borgne, directeur de la qualité et de l’ingénierie du Groupe PSA. La prochaine étape concernera la norme Euro-6.d-Temp, qui sera applicable à partir de septembre 2019. Cette dernière prendra également en compte les émissions polluantes (NOx, PN) mesurées en conditions de conduite réelles sur routes ouvertes ou RDE (Real Driving Emissions). Source : COMMUNIQUE DE PRESSE GROUPE PSA (29/8/18) Par Alexandra Frutos ALLEMAGNE BMW S’EST ASSOCIÉ À LUFTHANSA POUR PROMOUVOIR LA VISION INEXT Le constructeur allemand BMW s’est associé à la compagnie aérienne Lufthansa pour promouvoir la Vision iNext, sa voiture hautement automatisée et 100 % électrique. BMW a en effet organisé une tournée sur 5 jour pour présenter la Vision iNext en Europe, aux Etats- Unis et en Chine. -

Geely Automobile Holdings (175 HK)– BUY HKD12.00 Key Trends in China’S PV Market Over the Next Three Years: 1

Sector Initiation Hong Kong ! 5 May 2017 Consumer Cyclical | Automobiles & Components Neutral Automobiles & Components Stocks Covered: 3 Competition In The New Era Ratings (Buy/Neutral/Sell): 1 / 2 / 0 We expect growth in China’s PV market to slow to 5%/3% in 2017/2018 Top Pick Target Price respectively, due to diminishing effects of purchase tax cuts. We see three Geely Automobile Holdings (175 HK)– BUY HKD12.00 key trends in China’s PV market over the next three years: 1. Local brands to expand market share; 2. EV sales to grow at a higher pace vs fuel cars; 3. SUVs to continue to lead the market. China’s PV sales and growth rate on the uptrend Our sector Top Pick is Geely on its improved model portfolio and good synergy with Volvo. We also initiate coverage on BYD and GWM with NEUTRAL recommendations. Our sector call is NEUTRAL. We initiate coverage on China’s auto manufacturers with a NEUTRAL weighting. We expect passenger vehicles and minibus (collectively known as PV) sales in 2017/2018 to grow by 5%/3% respectively, slowing from 7%/15% registered in 2015/2016 respectively. This is as due to the diminishing effects of purchase tax discounts on cars with 1.6L displacement and below, to 25% starting 2017 from 50% in Oct 2015. Note that part of 2017’s PV sales were pre- sold in 2016, and part of PV sales in 2018 would be partially pre-sold in 2017. Solid growth expected in various segments, such as sport utility vehicles (SUVs), electric vehicles (EVs), smart vehicles, cars with displacements above 1.6L, premium brands, price-insensitive auto buyers, and in areas such as lower- Source: China Passenger Car Association (CPCA) tier cities. -

Pwc China Automobile Industry M&A Review and Outlook

Epidemic Prevention and Response to COVID-19 in the Automobile Industry Series Issue 2 — PwC China Automobile industry M&A Review and Outlook The epidemic has prompted many practitioners and managers in the industry to re-examine and plan for the medium-and long-term development of auto industry, accelerating industry transformation and upgrade. PwC auto team emphasizes on the following aspect of tax & legal, M&A and telematics system to analyze the related solutions. In this article, we mainly focus on the M&A aspect, hoping to give some inspirational idea to the practitioners in the industry. China’s automobile industry has developed rapidly in the opportunities. Moreover, an increasing number of companies past decade. Benefiting from “bringing in” and “going out” with advanced technology and capital will continue entering policy, both domestic and foreign OEMs have successfully into the market which fuels more M&A activities in the realized high growth through a series of mergers and automobile industry. acquisitions (M&A). Since 2018, the development of China In this article, we will analyze the automobile industry from automobile market has been slowing down, and the “CASE” four aspects: review of China’s auto industry M&A deals, trend has been having impact on OEMs. As new businesses main deal drivers and changes of auto industry, the future models are emerging, it has also led to blurring of M&A trend, and key initiatives in response to market boundaries between industries. Auto companies have been changes. actively using M&A deals to transform the automobile industry. At the beginning of 2020, the coronavirus outbreak severely impacted the supply chain of automobile industry, thus resulted in demands for business restructuring and transformation. -

Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Automobility in China Dr. Toni Marzotto

Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad Automobility in China Dr. Toni Marzotto “The mountains are high and the emperor is far away.” (Chinese Proverb)1 Title: The Rise of China's Auto Industry: Automobility with Chinese Characteristics Curriculum Project: The project is part of an interdisciplinary course taught in the Political Science Department entitled: The Machine that Changed the World: Automobility in an Age of Scarcity. This course looks at the effects of mass motorization in the United States and compares it with other countries. I am teaching the course this fall; my syllabus contains a section on Chinese Innovations and other global issues. This project will be used to expand this section. Grade Level: Undergraduate students in any major. This course is part of Towson University’s new Core Curriculum approved in 2011. My focus in this course is getting students to consider how automobiles foster the development of a built environment that comes to affect all aspects of life whether in the U.S., China or any country with a car culture. How much of our life is influenced by the automobile? We are what we drive! Objectives and Student Outcomes: My objective in teaching this interdisciplinary course is to provide students with an understanding of how the invention of the automobile in the 1890’s has come to dominate the world in which we live. Today an increasing number of individuals, across the globe, depend on the automobile for many activities. Although the United States was the first country to embrace mass motorization (there are more cars per 1000 inhabitants in the United States than in any other country in the world), other countries are catching up. -

Sustainability Report Bmw Brilliance Automotive Ltd. Contents

2015 SUSTAINABILITY REPORT BMW BRILLIANCE AUTOMOTIVE LTD. CONTENTS CONTENTS INTRODUCTION SUSTAINABILITY MANAGEMENT PRODUCT RESPONSIBILITY Preface 3 1.1 Our management approach 10 2.1 Our management approach 39 Our point of view 4 1.2 Stakeholder engagement 16 2.2 Efficient mobility 44 Highlights 2015 5 1.3 Compliance, anti-corruption and 18 2.3 Product safety 48 An overview of BMW Brilliance 6 human rights 2.4 Customer satisfaction 51 ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION SUPPLIER MANAGEMENT EMPLOYEES 3.1 Our management approach 57 4.1 Our management approach 72 5.1 Our management approach 87 3.2 Energy consumption and emissions 59 4.2 Minimising supplier risk 77 5.2 Attractive employer 90 3.3 Waste reduction 63 4.3 Utilising supplier opportunities 83 5.3 Occupational health and safety 96 3.4 Water 68 5.4 Training and development 99 CORPORATE CITIZENSHIP APPENDIX 6.1 Our management approach 107 7.1 About this report 120 6.2 Corporate citizenship 112 7.2 UN Global Compact index 121 7.3 GRI G4 content index 125 2 PREFACE Next, a further step in developing China’s very own new energy vehicle brand. In the future, we will expand our offering of locally developed, produced and environmentally friendly premium vehicles for our Chinese customers. Digitalisation is an important driver for sustainability. We are developing new solutions for intelligent mobility AT BMW BRILLIANCE, WE SEE SUSTAINABILITY AS products and services. At the same time, we are increasing the quality of our products, as well as the speed A KEY TO OUR CONTINUOUS SUCCESS IN CHINA. -

Official Journal L 315 of the European Union

Official Journal L 315 of the European Union ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ Volume 57 English edition Legislation 1 November 2014 Contents II Non-legislative acts REGULATIONS ★ Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 1170/2014 of 29 October 2014 correcting the Slovenian version of Commission Regulation (EC) No 504/2008 implementing Council Directives 90/426/EEC and 90/427/EEC as regards methods for the identification of equidae (1) 1 ★ Commission Regulation (EU) No 1171/2014 of 31 October 2014 amending and correcting Annexes I, III, VI, IX, XI and XVII to Directive 2007/46/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing a framework for the approval of motor vehicles and their trailers, and of systems, components and separate technical units intended for such vehicles (1) .................. 3 Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) No 1172/2014 of 31 October 2014 establishing the standard import values for determining the entry price of certain fruit and vegetables ...................... 13 DECISIONS 2014/768/EU: ★ Commission Implementing Decision of 30 October 2014 establishing the type, format and frequency of information to be made available by the Member States on integrated emission management techniques applied in mineral oil and gas refineries, pursuant to Directive 2010/75/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council (notified under document C(2014) 7517) (1) .............................................................................................................. 15 2014/769/EU: ★ Commission Implementing Decision of 30 October 2014 confirming or amending the average specific emissions of CO2 and specific emissions targets for manufacturers of new light commercial vehicles for the calendar year 2013 pursuant to Regulation (EU) No 510/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council (notified under document C(2014) 7863) ................... -

GUANGZHOU AUTOMOBILE GROUP CO., LTD. 廣州汽車集團股份有限公司 (A Joint Stock Company Incorporated in the People’S Republic of China with Limited Liability) (Stock Code: 2238)

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. GUANGZHOU AUTOMOBILE GROUP CO., LTD. 廣州汽車集團股份有限公司 (a joint stock company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) (Stock Code: 2238) 2016 INTERIM RESULTS ANNOUNCEMENT I. IMPORTANT NOTICE (I) The Board, the supervisory committee and the directors, supervisors and senior management of the Company warrant that the contents contained herein are true, accurate and complete. There are no false representations or misleading statements contained in or material omissions from this announcement, and they will jointly and severally accept responsibility. (II) All directors of the Company have attended the meetings of the Board. (III) The interim financial report of the Company is unaudited. The Audit Committee of the Company has reviewed the unaudited interim results of the Company for the six months ended 30 June 2016 and agreed to submit it to the Board for approval. (IV) Zhang Fangyou, the Chairman of the Company, Zeng Qinghong, the General Manager of the Company, Wang Dan, the person in charge of accounting function and Li Canhui, the manager of the accounting department (Chief of Accounting), warrant the truthfulness, accuracy and completeness of the financial report contained in this announcement. (V) The Board of the Company proposed payment of interim dividend of RMB0.8 (tax inclusive) in cash for every 10 shares to all shareholders. -

KEY TOOL .Cdr

NO. Brand Remote Type NO. Brand Remote Type NO. Brand Remote Type NO. Brand Remote Type 1 GQ43VT13T-315 215 After 2006 M6/2011 before M3 315 327 MG3 Wireless remote transponder 46 118 13 Sunny/Sylphy/Tiida radio w ave MG 2 GQ43VT13T-433 216 2006 before M6 315 328 MG5 Wireless remote transponder 46 119 Nissan VDO(Trunk w ith panic) 315 329 D50/R50 315 3 Chrysier Chrysier 300C 315 version 2 217 After 2011 M3/M6 433 120 Nissan VDO 315 330 Venucia R30 433 4 Chrysier 300C 315 218 11 M3/M6 classic folding 433 331 T70 315 5 Chrysier 300C 433 121 Nissan VDO 433 219 Mazda 41846 41805 313M 332 Saima (Mitsubishi system V73) 6 After 2012 Excelle 433 122 Nissan 433 220 41846_41805-TW 313M HF 333 Saibao/Saima/Lubao 315 7 GL8/CenturyGM2-3/Regal 315M 123 Yumsun/Oting 221 M5/M2 MITSUBISHI systems 315 334 15 E3 433 8 GL8 Nissan 124 New Sylphy folding 222 M5 433 335 9DW315 9 Excelle 315 223 M2 336 QQ 9AK 315 10 Buick Excelle 315.5 125 Trunk w ith panic 315 224 2008 before Jiefang 315 337 QQ 9CN 315 12 New Hummer H2/Enclave /GMC 126 P2700 225 2009 before Weile 315 338 QQ 9DW 433 13 Buick all models 127 P2700 226 After 2010 Jiefang 315 339 QQ 9EU 433 14 The Old Excelle 433 128 Bluebird 227 After 2013 Jiefang 315 340 A3/A5 w ith boot 315 15 First Land 341 A3/A5 w ithout boot 433 129 Tiida/Sunny/14 Sylphy 433 228 15 Jiefang J6 folding 315 16 11 Mondeo-Zhisheng/12-15 Focus/KUGA 433 342 A3/A5 w ithout boot 315 130 Subaru 315 229 FAW Xiali N5 Weizhi 315 (duplicable) 17 Focus/Mondeo/Fiesta 343 Chery A3/A5 w ith boot/Fengyun 2 433 230 Weizhi 315 18 Focus folding -

Understanding Auto Fincos

Global Research 18 March 2019 Fundamental Analytics Equities Behind the numbers: Autos Global Valuation, Modelling & Accounting Geoff Robinson, CA FCA Analyst [email protected] +44-20-7567 1706 Julian Radlinger, CFA Analyst [email protected] +44-20-7568 1171 Renier Swanepoel Analyst [email protected] +44-20-7568 9025 Patrick Hummel, CFA Analyst [email protected] +41-44-239 79 23 Guy Weyns, PhD Analyst We launch the second of our series of collaborative sector analyses … [email protected] The Fundamental Analytics team has teamed up with the UBS Global Auto Sector team +65-6495 3507 (17 analysts across six regions) to deliver the second in its series of collaborative reports Paul Gong (see the first one on pharmaceuticals here). This report focuses on all things Autos. It is Analyst written to (1) provide investors new to Autos with an exhaustive overview of everything [email protected] that's relevant to understand the sector from an industry and company perspective, (2) +852-2971 7868 help new and seasoned investors alike frame their financial statement and earnings Colin Langan, CFA quality analysis, and (3) provide a guide to the most commonly used accounting Analyst practices and pitfalls specific to the sector, how to spot them, interpret and adjust for [email protected] +1-212-713 9949 them. This report is the go-to Global Auto sector hand-book for equity investors. Kohei Takahashi … including a detailed global sector run-through … Analyst Our report starts with a ~50-page sector primer written on the basis of the combined [email protected] expertise and wealth of resources of the UBS Global Auto Sector team. -

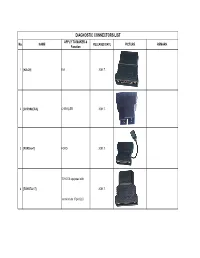

DIAGNOSTIC CONNECTORS LIST APPLY to MAKER & No

DIAGNOSTIC CONNECTORS LIST APPLY TO MAKER & No. NAME RELEASED DATE PICTURE REMARK Function 1 [KIA-20] KIA 2001.7. 2 [CHRYSLER-6] CHRYSLER 2001.7. 3 [FORD-6+1] FORD 2001.7. TOYOTA equipped with 4 [TOYOTA-17] 2001.7. semicircular 17pin DLC 5 [MITSUBISHI/HYUNDAI-12+16] MITSUBISHI & HYUNDAI 2002.11. 6 [HONDA-3] HONDA 2002.11. MAZDA equipped with 7 [MAZDA-17] 2002.12. semicircular 17pin DLC 8 [HAIMA-17] HAINAN MAZDA 2002.12. Most maker any model 9 [SMART OBDII-16] 2002.5. without CAN BUS 10 [NISSAN-14+16] NISSAN 2003.10. 11 [CHANGAN-3] CHANGAN 2003.11. 12 [JIANGLING-16] JIANGXI ISUZU 2003.3. 13 [SUZUKI-3] SUZUKI 2003.3. 14 [ZHONGHUA-16] ZHONGHUA CAR 2003.3. 15 [HAINAN MAZDA-17F] HAINAN MAZDA 2003.4. 16 [AUDI-4] AUDI 2003.6. 17 [DAIHATSU-4] DAIHATSU 2003.6. 18 [BENZ-38] BENZ 2003.7. 19 [UNIVERSAL-3] BENZ 2003.7. 20 [BMW-20] BMW 2003.9. All BMW models with 16 pin 21 [BMW-16] 2003.9. DLC 22 [HAIMA-16] HAINAN MAZDA 2004.10. 23 [FIAT-3] FIAT 2004.10. 24 [HAIMA-3] HAINAN MAZDA 2004.10. 25 [FORD-20] Australia FORD 2004.11. For 2002- LX470 and LAND 26 [TOYOTA-16] TOYOTA 2004.11. CRUISE 27 [HONDA5] HONDA 2004.11. Only for Russian HONDA 28 [GM/VAZ-12] GMVAZ 2004.3. 29 [DAEWOO-12] DAEWOO,SPARK 2004.3. 30 [SEDAN-3] VW models in Mexico 2004.3. Only for Mexico 31 [COMBI-4] VW models in Mexico 2004.3. Only for Mexico 32 [GAZ-12] GAZ 2004.5.