A Gis Predictive Model for Paleoindian Sites in Yellowstone National Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Working Together to Preserve the Past

CUOURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT information for Parks, Federal Agencies, Trtoian Tribes, States, Local Governments, and %he Privale Sector <yt CRM TotLUME 18 NO. 7 1995 Working Together to Preserve the Past U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR National Park Service Cultural Resources PUBLISHED BY THE VOLUME 18 NO. 7 1995 NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Contents ISSN 1068-4999 To promote and maintain high standards for preserving and managing cultural resources Working Together DIRECTOR to Preserve the Past Roger G. Kennedy ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR Katherine H. Stevenson The Historic Contact in the Northeast EDITOR National Historic Landmark Theme Study Ronald M. Greenberg An Overview 3 PRODUCTION MANAGER Robert S. Grumet Karlota M. Koester A National Perspective 4 GUEST EDITOR Carol D. Shull Robert S. Grumet ADVISORS The Most Important Things We Can Do 5 David Andrews Lloyd N. Chapman Editor, NPS Joan Bacharach Museum Registrar, NPS The NHL Archeological Initiative 7 Randall J. Biallas Veletta Canouts Historical Architect, NPS John A. Bums Architect, NPS Harry A. Butowsky Shantok: A Tale of Two Sites 8 Historian, NPS Melissa Jayne Fawcett Pratt Cassity Executive Director, National Alliance of Preservation Commissions Pemaquid National Historic Landmark 11 Muriel Crespi Cultural Anthropologist, NPS Robert L. Bradley Craig W. Davis Archeologist, NPS Mark R. Edwards The Fort Orange and Schuyler Flatts NHL 15 Director, Historic Preservation Division, Paul R. Huey State Historic Preservation Officer, Georgia Bruce W Fry Chief of Research Publications National Historic Sites, Parks Canada The Rescue of Fort Massapeag 20 John Hnedak Ralph S. Solecki Architectural Historian, NPS Roger E. Kelly Archeologist, NPS Historic Contact at Camden NHL 25 Antoinette J. -

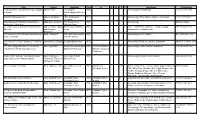

Archeology Inventory Table of Contents

National Historic Landmarks--Archaeology Inventory Theresa E. Solury, 1999 Updated and Revised, 2003 Caridad de la Vega National Historic Landmarks-Archeology Inventory Table of Contents Review Methods and Processes Property Name ..........................................................1 Cultural Affiliation .......................................................1 Time Period .......................................................... 1-2 Property Type ...........................................................2 Significance .......................................................... 2-3 Theme ................................................................3 Restricted Address .......................................................3 Format Explanation .................................................... 3-4 Key to the Data Table ........................................................ 4-6 Data Set Alabama ...............................................................7 Alaska .............................................................. 7-9 Arizona ............................................................. 9-10 Arkansas ..............................................................10 California .............................................................11 Colorado ..............................................................11 Connecticut ........................................................ 11-12 District of Columbia ....................................................12 Florida ........................................................... -

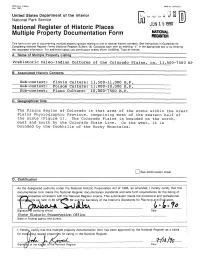

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation

NPS Form 10-900-b OMB .vo ion-0018 (Jan 1987) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places JUH151990' Multiple Property Documentation Form NATIONAL REGISTER This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing___________________________________________ Prehistoric Paleo-Indian Cultures of the Colorado Plains, ca. 11,500-7500 BP B. Associated Historic Contexts_____________________________________________ Sub-context; Clovis Culture; 11,500-11,000 B.P.____________ sub-context: Folsom Culture; 11,000-10,000 B.P. Sub-context; Piano Culture: 10,000-7500 B.P. C. Geographical Data___________________________________________________ The Plains Region of Colorado is that area of the state within the Great Plains Physiographic Province, comprising most of the eastern half of the state (Figure 1). The Colorado Plains is bounded on the north, east and south by the Colorado State Line. On the west, it is bounded by the foothills of the Rocky Mountains. [_]See continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of relaje«kproperties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional renuirifiaejits set forth in 36 CFSKPaV 60 and. -

Title Author Publisher Date in V. Iss. # C. Key Words Call Number

Title Author Publisher Date In V. Iss. # C. Key Words Call Number Field Manual for Avocational Archaeologists Adams, Nick The Ontario 1994 1 Archaeology, Methodology CC75.5 .A32 1994 in Ontario Archaeological Society Inc. Prehistoric Mesoamerica Adams, Richard E. Little, Brown and 1977 1 Archaeology, Aztec, Olmec, Maya, Teotihuacan F1219 .A22 1991 W. Company Lithic Illustration: Drawing Flaked Stone Addington, Lucile R. The University of 1986 Archaeology 000Unavailable Artifacts for Publication Chicago Press The Bark Canoes and Skin Boats of North Adney, Edwin Tappan Smithsonian Institution 1983 1 Form, Construction, Maritime, Central Canada, E98 .B6 A46 1983 America and Howard I. Press Northwestern Canada, Arctic Chappelle The Knife River Flint Quarries: Excavations Ahler, Stanley A. State Historical Society 1986 1 Archaeology, Lithic, Quarry E78 .N75 A28 1986 at Site 32DU508 of North Dakota The Prehistoric Rock Paintings of Tassili N' Mazonowicz, Douglas Douglas Mazonowicz 1970 1 Archaeology, Rock Art, Sahara, Sandstone N5310.5 .T3 M39 1970 Ajjer The Archeology of Beaver Creek Shelter Alex, Lynn Marie Rocky Mountain Region 1991 Selections form the 3 1 Archaeology, South Dakota, Excavation E78 .S63 A38 1991 (39CU779): A Preliminary Statement National Park Service Division of Cultural Resources People of the Willows: The Prehistory and Ahler, Stanley A., University of North 1991 1 Archaeology, Mandan, North Dakota E99 .H6 A36 1991 Early History of the Hidatsa Indians Thomas D. Thiessen, Dakota Press Michael K. Trimble Archaeological Chemistry -

Late Paleoindian Land Tenure in Southwest Wyoming: Towards

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Anthropology Department Theses and Dissertations Anthropology, Department of 2019 Late Paleoindian Land Tenure in Southwest Wyoming: Towards Integrating Method and Theory in an Analysis of Taphochronometric Indicators of Time-Averaged Deposits in the Wyoming Basin, Wyoming USA Cynthia D. Highland University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/anthrotheses Part of the Anthropology Commons Highland, Cynthia D., "Late Paleoindian Land Tenure in Southwest Wyoming: Towards Integrating Method and Theory in an Analysis of Taphochronometric Indicators of Time-Averaged Deposits in the Wyoming Basin, Wyoming USA" (2019). Anthropology Department Theses and Dissertations. 61. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/anthrotheses/61 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Anthropology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology Department Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. LATE PALEOINDIAN LAND TENURE IN SOUTHWEST WYOMING: TOWARDS INTEGRATING METHOD AND THEORY IN AN ANALYSIS OF TAPHOCHRONOMETRIC INDICATORS OF TIME-AVERAGED DEPOSITS IN THE WYOMING BASIN, WYOMING USA by CYNTHIA D. HIGHLAND A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Major: Anthropology Under the Supervision of Professor LuAnn Wandsnider Lincoln, Nebraska December 2019 LATE PALEOINDIAN LAND TENURE IN SOUTHWEST WYOMING: TOWARDS INTEGRATING METHOD AND THEORY IN AN ANALYSIS OF TAPHOCHRONOMETRIC INDICATORS OF TIME-AVERAGED DEPOSITS IN THE WYOMING BASIN, WYOMING USA Cynthia D. -

An Assessment of the Impact of Resharpening on Paleoindian Projectile Point Blade Shape Using Geometric Morphometric Techniques

Chapter 11 An Assessment of the Impact of Resharpening on Paleoindian Projectile Point Blade Shape Using Geometric Morphometric Techniques Briggs Buchanan and Mark Collard Abstract Paleoindian archaeologists have long recognized that resharpening has the potential to affect the shape of projectile points. So far, however, the impact of resharpening on the distinctiveness of the blades of Paleoindian projectile points has not been investigated quantitatively. With this in mind, we used geometric morphometric techniques to compare the blades of Clovis, Folsom, and Plainview projectile points from the Southern Plains of North America. We evaluated two hypotheses. The first was that blade shape distinguishes the three types. We found that blade shape distinguished Clovis points from both Folsom and Plainview points, but did not distinguish Folsom points from Plainview points. The second hypothesis we tested was that resharpening eliminates blade shape differences among the types. To test this hypothesis, we used size as a proxy for resharpening. The results of this analysis were similar to those obtained in the first analysis. Thus, our study suggests that, contrary to what is often assumed, resharpening does not automatically undermine the use of blade shape in Paleoindian projectile point typologies. Introduction The assignment of projectile points to types is critical for research on the Paleoindian period in North America. Paleoindian specialists rely on projectile point typology to situate assemblages in time when directly dateable material is not recovered. Furthermore, because Paleoindian points are found in such high numbers in mixed or isolated surface contexts, many studies concerning changes in technology and land use have relied on typed specimens (e.g., Anderson and Faught 2000). -

Lithic Technology at the Below Forks Site, Fhng-25: Strategems of Stone Tool Manufacture

Lithic Technology at The Below Forks Site, FhNg-25: Strategems of Stone Tool Manufacture. A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Archaeology University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. By Steven C. Kasstan March 2004. © 2004 (Copyright Steven C. Kasstan. All Rights Reserved.) PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying of this thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made of any material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or make other use of material in this thesis in whole or in part should be addressed to: Head of the Department of Archaeology, University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. S7N 2A5. i ABSTRACT The Below Forks site is a deeply stratified multicomponent archaeological site situated two kilometres downstream from the confluence of the North and South Saskatchewan Rivers. -

In 1916, a Sheep Rancher Named William Spencer Discovered Bones

n 1916, a sheep rancher named William Spencer discovered get professionals interested in looking at the site. Due to McJunkin’s Cody, and Mule Creek Junction in Wyoming) the Yuma category definition of these types in conjunction with the well-stratified bones and human artifacts in Moss Agate Arroyo outside efforts, professionals in 1927 confirmed the artifacts were associated was split into Eden, Cody, and Agate Basin complexes. Other sites deposits contributed data to important typological debates of the Iof Mule Creek Junction in east-central Wyoming. He with extinct bison from the Late Pleistocene 10,000 to 11,000 years outside of Wyoming, for example Scottsbluff in Nebraska, yielded 1950s and 1960s. picked some of these up and kept them. In 1919, a cowboy ago. This marked the beginning of Paleoindian archaeology in the similar single component finds that accounted for other varieties of But it is more than just a type-site. The significance of Hell Gap naturalist by the name of George McJunkin also discovered Americas. Ten years later Spencer’s site became the type site for the the overarching Yuma category. Today all three of these Wyoming extends far beyond its important contribution to establishing the bones in an arroyo with human artifacts outside of Folsom, New Agate Basin complex, one of the major North American Paleoindian sites are nationally recognized with listings of Agate Basin and Finley Paleoindian chronology. The site has provided and continues Mexico. He picked some of these up, kept them, and tried to complexes. This year we celebrate 100 years since Spencer’s discovery in the National Register of Historic Places and Horner as a National to provide a wealth of information on early North American at Agate Basin, as well as other significant Wyoming Paleoindian Historic Landmark. -

Pelican Lake Complex

An Overview of Archeology in North Dakota .................................................................... 1 Study Units for the Archeological Component ............................................................... 1 Definitions for “Archeological Site” and the Problem of Properties which Straddle Study Unit Borders ......................................................................................................... 4 Study Units Vis-à-Vis Traditional Archeological Spatial Units ..................................... 8 Archeological Unit Terms............................................................................................. 10 Cultural Traditions .................................................................................................... 10 Cultural Complexes .................................................................................................. 12 Components .............................................................................................................. 13 Phases ........................................................................................................................ 13 Cultural Periods ........................................................................................................ 13 Dates and Dating Methods ................................................................................... 14 The Named Cultural Traditions .................................................................................... 17 The Paleo-Indian Tradition ...................................................................................... -

The Osprey Beach Locality: a Cody Complex Occupation on the South Shore of West Thumb

The Osprey Beach Locality: A Cody Complex Occupation on the South Shore of West Thumb Mack William Shortt In early August 2000, a group of Wichita State archeology students under the direction of Donald Blakeslee recovered four diagnostic stone tools from a beach on the shore of West Thumb. While the entire area yielded a variety of artifacts, these particular specimens were typical of an Early Precontact-period (Paleoindian) archeological unit known as the Cody Complex. Of particular interest was the knowledge that Cody components at archeological sites else- where have provided radiocarbon dates of ca. 10,000 and 8,000 radiocarbon years before the present (RCYBP) (Stanford 1999: 321, Table 7). Clearly, these artifacts were much older than the other archeological materials found by Blakeslee’s crew at the time. The portion of the beach where the specimens were found was ultimately named the Osprey Beach Locality.To date, Osprey Beach is the oldest, best-preserved Precontact site in Yellowstone National Park. As such, its study will provide an excellent opportunity to gather information about the lifeways of Yellowstone’s early human occupants. The Cody Complex was first defined in 1951 at the Horner site, a bison kill located to the east of Yellowstone National Park near Cody,Wyoming (e.g., Frison and Todd 1987; Frison 1991). Horner subsequently became the type site for the Cody Complex because of the occurrence of diagnostic Eden and Scottsbluff projectile points and specialized, bifacially flaked tools referred to as Cody knives. Radiocarbon dates from Horner range from approximately 9,300 to 8,700 RCYBP (Frison and Todd 1987: 98; Frison and Bonnichsen 1996: 313). -

Explanations for Morphological Variability in Projectile Points: a Case Study from the Late Paleoindian Cody Complex Cheryl Fogle-Hatch

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Anthropology ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-1-2015 Explanations For Morphological Variability In Projectile Points: A Case Study From The Late Paleoindian Cody Complex Cheryl Fogle-Hatch Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/anth_etds Part of the Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Fogle-Hatch, Cheryl. "Explanations For Morphological Variability In Projectile Points: A Case Study From The Late Paleoindian Cody Complex." (2015). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/anth_etds/22 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cheryl K. Fogle-Hatch Candidate Anthropology Department This dissertation is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Dissertation Committee: Dr. Bruce B. Huckell, Chairperson Dr. Lawrence G. Strauss, Co-Chairperson Dr. E. James Dixon Dr. Mary Lou Larson i EXPLANATIONS FOR MORPHOLOGICAL VARIABILITY IN PROJECTILE POINTS A CASE STUDY FROM THE LATE PALEOINDIAN CODY COMPLEX BY CHERYL K. FOGLE-HATCH Bachelor of Arts, Journalism, University of Arizona, 1998 Master of Arts, Anthropology, University of New Mexico, 2000 Doctor of Philosophy, University of New Mexico, 2015 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico May, 2015 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I heartily thank my committee chair Bruce Huckell for his guidance and for continuing to work with me after I moved across the country. -

Fluted-U Nflu Te D Folsom Poin Ts

THE EVOLUTION OF FOLSOM FLUTING Douglas H. MacDonald DO NOT CITE IN ANY CONTEXT WITHOUT PERMISSION OF THE AUTHOR Douglas H. MacDonald, Department of Anthropology, The University of Montana, Missoula, MT 59812 ([email protected]) 1 The emergence and evolution of the Folsom point is analyzed in light of cultural transmission and dual inheritance theories. While the Folsom point was an outstanding techno-functional solution to Late Pleistocene bison hunting of the Great Plains of North America, archaeological data indicate that fluting was an unnecessary high-risk activity that served as much a socio- cultural role as a techno-functional one. In dual inheritance terms, the fluting of Folsom points likely gained a foothold as one piece of the “good hunter” model which was passed from elders to youths within specific cultural contexts. The demise of Folsom points during the earliest Holocene likely was instigated by a transformation of social image, from fluting as an indicator trait of success, to fluting as a measure of increased risk and waste in the face of challenging subsistence realms. 2 Spanish Abstract page (to be completed if accepted) 3 The fluted Folsom point is one of the most well-known projectile point styles in human prehistory. However, its precise role within Folsom culture has long been a topic of debate among American archaeologists. From techno-functional to socio-religious, various explanations have been proposed to explain the perplexing practice of fluting Folsom points. In this paper, I review these prior explanations for Folsom fluting, as well as introduce a supplementary explanatory model based in cultural transmission and dual inheritance theories.