7173 SBJT V11N3.1.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Betekenis Van Bijbelse Woorden En (Plaats)Namen

Betekenis van Bijbelse woorden en (plaats) namen Abel Beth-maacha rouw van (of weide van) het huis van A verdrukking (...onderdrukking; ...neerslachtigheid; Aar teder-zijn ...benauwd Aaron lichtbrenger Abel Keramim weide van de wijngaarden Aäron Abel-Beth-maacha rouw van (of weide van) het huis van verdrukking Aaronieten (...onderdrukking; ...neerslachtigheid; ...benauwd Aartsengel voornaamste van de engelen Abel-bet-maaka stad in Noord-Israël bij een stad in het Ab vader noorden van Israël bij Beth-maacha; de plaats waar de ark rustte op de Ab vader van iemand akker van Jozua te Beth-Semes Abaddon plaats van verderf, verderf, ruine Abel-bet-maaka rouw van (of weide van) het huis van verdrukking Abaddon verderf (...onderdrukking; ...neerslachtigheid; ...benauwd Abagta door God geschonken Abel-Bet-Maäka huis van druk Abagtha Abel-Hassittim weide van acacias of rouw van de Abana steun acasia Abana bestendige, onveranderlijk, een zekere Abel-keramim weide van de wijngaarden verordening Abel-maim weide van wateren of rouw van de Abarim gebieden aan de overzijde wateren Abarim ruïnen van Abarim Abel-mechola weide van het dansen of rouw van de wijngaard of rouwdans Abba vader Abel-mehola Abda dienaar van JHWH, dienst Abel-misraim weide van Egypte of rouw van de Abdeel dienaar van God Egyptenaren Abdi dienaar van JHWH, mijn dienaar Abel-mizraim Abdiel dienaar van God Abel-sittim weide van acacias of rouw van de acasia Abdiël Abi mijn vader Abdon dienstbaar, slavernij; onderworpenheid Abi Gibon vader van Gibeon Abednego dienaar van Nebo, dienaar van de schittering Abia mijn vader is Jah (Jehovah) Abed-nego Abia JHWH is (mijn) vader Abel adem Abialbon El (God) is mijn vader of mijn vader is groot van begrip of vader van begrip Abel ijdelheid (verstand) Abel plaatsnaam, stad in Noord-Israël bij Abi-albon een stad in het noorden van Israël bij Beth-maacha. -

The Chapters of Romans

Liberty University Scholars Crossing An Alliterated Outline for the Chapters of the Bible A Guide to the Systematic Study of the Bible 5-2018 The Chapters of Romans Harold Willmington Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/outline_chapters_bible Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Willmington, Harold, "The Chapters of Romans" (2018). An Alliterated Outline for the Chapters of the Bible. 58. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/outline_chapters_bible/58 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the A Guide to the Systematic Study of the Bible at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in An Alliterated Outline for the Chapters of the Bible by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Romans SECTION OUTLINE ONE (ROMANS 1) Paul opens his letter to the Roman church by talking about God's anger with sin. The opening chapter may be thought of as a trial, where God is the judge and sinful humans are the accused. I. THE COURT RECORDER (1:1-17): Here Paul, author of Romans, provides his readers with some pretrial introductory material. A. His credentials (1:1, 5): Paul relates four facts about himself. 1. He is a servant of Jesus (1:1a). 2. He is an apostle (1:1b). 3. He has been set apart to preach the gospel (1:1c). 4. He is a missionary to the Gentiles (1:5). B. His Christ (1:2-4) 1. -

Junia – a Woman Lost in Translation: the Name IOYNIAN in Romans 16:7 and Its History of Interpretation

Open Theology 2020; 6: 646–660 Women and Gender in the Bible and the Biblical World Andrea Hartmann* Junia – A Woman Lost in Translation: The Name IOYNIAN in Romans 16:7 and its History of Interpretation https://doi.org/10.1515/opth-2020-0138 received June 30, 2020; accepted October 27, 2020 Abstract: The name of the second person greeted in Romans 16:7 is given as IOYNIAN, a form whose gramma- tical gender could be either feminine or masculine which leads to the question: Is it Junia or Junias – awomanor aman– who is greeted alongside Andronicus as “outstanding among the apostles?” This article highlights early influential answers to this question in the history of interpretation (John Chrysostom’scommentary,thedisciple- ship list of Pseudo-Epiphanius, Luther’s translation, and Calvin’s interpretation) showing that societal percep- tions of women’s roles were a factor in how they interpreted IOYNIAN. The article then summarises the last 150 years of interpretation history which saw (a) the disappearance of Junia from the text and from scholarly discussion due to the impact of the short-from hypothesis in the nineteenth century, (b) the challenge to this male interpretation in connection with second wave feminism, and (c) the restoration of the female reading in the ensuing debate. Bringing together the main lines of the argument, it will be shown that there is only one reading supported by the evidence, the female reading which throughout the centuries was the more difficult reading in light of the church’sandsociety’s perception of women’s -

Epistles of Paul

THE ROLE OF WOMEN IN THE ASSEMBLY: EPISTLES OF PAUL THE ROLE OF WOMEN IN THE ASSEMBLY: EPISTLES OF PAUL JACK P. LEWIS In the Gospels, we see women showing hospitality to Jesus, women supplying him with their means, and women travel- ing with him and being around the cross. We see Jesus healing women, dealing with their spiritual problems, and using women as illustrations in his teaching; but we do not find any instruc- tion about their role in assemblies. The same is true of the book of Acts. Women learn; they obey the gospel; they engage in good works; they show hospitality; and they participate in giving. They are not depicted as being evangelists; they do not exercise miracle-working power; they do not baptize people; they are not elders in the congregations; and they are not pastors. No passage in the Acts of the Apostles specifically deals with the role of women in assemblies. We will turn to the epistles of Paul. Much of what Paul wrote is gender inclusive, relevant to and binding equally on men and women. Paul uses women as illustrations in his teaching. He con- trasts Hagar and Sarah (Gal 4:24ff.) and declares that the Jerusa- lem above is our mother (Gal 4:26). He speaks fondly of women as his fellow workers. The writer of the Epistle to the Hebrews includes women: Sarah, Moses’s mother, Rahab the harlot, and those who received their dead by resurrection (Heb 11:35). The Epistle of James mentions Rahab (Jas 2:25). Peter praises Sarah (1 Pet 3:6) as a model for Christian women. -

E.A. Judge, "The Roman Base of Paul's Mission," Tyndale Bulletin 56.1

Tyndale Bulletin 56.1 (2005) 103-117. THE ROMAN BASE OF PAUL’S MISSION E. A. Judge Summary One third of those around St Paul bear Latin names, ten times more than we should expect. The types of name used suggest that most of these should have held Roman citizenship or the preliminary rank of Junian Latin. In the Greek-speaking cities of the Roman East, however, most Romans or Latins kept the Greek names they or their ancestors had used before their enfranchisement or manumission. For day-to-day purposes the Greek names alone were cited, though technically now cognomina (‘associated names’) to the Latin praenomina (‘first names’) and nomina gentilicia (‘family names’) required by Roman usage. It is therefore likely that over half of Paul’s associates ranked as Roman. If so, the view that Acts has only made Paul himself a Roman citizen as window-dressing becomes pointless. Instead we should assume that he linked himself with other Romans used to travelling on business or able to offer hospitality to him and his mission. Introduction There are far too many Latin names around St Paul for them to be explained mostly as loan-words domesticated into the Greek name- stock.1 In an ‘eyewitness account’ of ‘going to church in the first 1 E. A. Judge, ‘The early Christians as a scholastic community: Part II’, Journal of Religious History, 1.3 (1961): 130, slid over this distinction. It was left unsettled by A. N. Sherwin-White, Roman Society and Roman Law in the New Testament (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1963): 156-62. -

Tusculum Hills Baptist Church Paul Gunn, Pastor PAUL's GRATITUDE

Tusculum Hills Baptist Church Paul Gunn, Pastor PAUL’S GRATITUDE FOR ALL THE HELP Romans 16:1-15 September 16, 2018 For public use: See non-copyright comments at the end of the message. The title of my message today is “Paul’s Gratitude For All The Help” and I’ll be preaching from Romans 16:1-15. I have two points to my message today and here they are: • Paul recognized his many helpers on the Lord’s work • Paul recognized the diversity of helpers INTRODUCTION: If you merely look at Romans 16 at a glance, you’ll see a list of names. If you’ve been keeping up with our study, then you may have looked ahead and wondered how a sermon could come out of a list of names. I must say I wondered that as well! Then it hit me. Romans is very similar to the book of Acts in that we have glimpses of the early church. Many things the two books deal with could be summed up in “What to do when” statements. The coming together of people with different backgrounds all because of Christ was a wonderful thing. It was a miracle of God indeed, but it didn’t come without some confusion and effort. People’s minds had to be opened like they had never been opened before. After writing such an incredible letter, before Paul closed out, he addressed some people directly. All people were significant to Paul. Some of them we know about, some of them we don’t. Listen and gain from the preaching of the scripture today. -

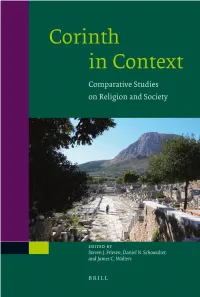

Corinth in Context Supplements to Novum Testamentum

Corinth in Context Supplements to Novum Testamentum Executive Editors M. M. Mitchell Chicago D. P. Moessner Dubuque Editorial Board L. Alexander, Sheffield – C. Breytenbach, Berlin J. K. Elliott, Leeds – C. R. Holladay, Atlanta M. J. J. Menken, Tilburg – J. Smit Sibinga, Amsterdam J. C. Thom, Stellenbosch – P. Trebilco, Dunedin VOLUME 134 Corinth in Context Comparative Studies on Religion and Society Edited by Steven J. Friesen, Daniel N. Schowalter, and James C. Walters LEIDEN • BOSTON 2010 Cover illustration: Corinth, with Acrocorinth in the background. Photo by Larry Cripe. Th is book is also published as hardback in the series Supplements to Novum Testamentum, ISSN 0167-9732 / edited by Steven Friesen, Dan Schowalter, and James Walters. 2010. ISBN 978 90 04 18197 7 Th is book is printed on acid-free paper. ISBN 978 90 04 18211 0 Copyright 2010 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, Th e Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to Th e Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. printed in the netherlands CONTENTS List of Illustrations ............................................................................ vii Acknowledgments .............................................................................. xvii List of Abbreviations ......................................................................... xix List of Contributors .......................................................................... -

January 2003

January 2014 SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT Strict fast: No = fish 19/ 20/ 21/ 22/ meat, dairy, fish, permitted 1 2 3 4 oil or wine Martyr Boniface +Ignatius the God- Martyr Juliana Martyr Anastasia and Aglaïs Bearer, Pre-feast of the deliverer Oil & wine the Nativity permitted from poisons 23/5 24/6 25/7 26/8 27/9 28/10 29/11 +SUNDAY BEFORE Righteous- + THE NATIVITY +SYNAXIS OF OUR +Stephen the The Holy 20,000 The 14,000 THE NATIVITY. Ten Martyr Eugenia ACCORDING TO MOST HOLY LADY, Protomartyr, Martyrs in infants slain by Martyrs of Crete, THE FLESH OF OUR MOTHER OF GOD Apostle and Nicomedia Herod Righteous LORD, GOD AND AND EVER-VIRGIN SAVIOUR JESUS MARY Archdeacon Naoum CHRIST. 30/12 31/13 1/14 2/15 3/16 4/17 5/18 +SUNDAY BEFORE Righteous +THE Sylvester; Pope Prophet Synaxis of the 70 Righteous THEOPHANIA/EPIP Melanie of CIRCUMCISION of Rome Pre- Malachias Apostles Synklētikē HANY Righteous- Rome Apodosis OF JESUS CHRIST, feast of (Malachi) Martyr Anysia of the Nativity BASIL THE Theophania/Epip GREAT hany 6/19 7/20 8/21 9/22 10/23 11/24 12/25 +THEOPHANIA/ +THE SYNAXIS OF Righteous Martyr Gregory of Nyssa, +RIGHTEOUS Martyr Tatiana EPIPHANY THE HONORABLE Domnica, Polyeuktos, Righteous THEODOSIOS FORERUNNER Dometianus George the Righteous THE CENOBITE Chozebite Eustratios 13/26 14/27 15/28 16/29 17/30 18/31 +SUNDAY AFTER Righteous-Martyrs Righteous John +The Veneration +Righteous +Athanasios THEOPHANIA/EPIP of Sinai and Raïtho, the Hut-Dweller of the Chains of Anthony the and Cyril of HANY Martyrs Apodosis of and Paul of the Apostle Peter Great, New- Alexandria Hermylos and Epiphany Thebes Stratonikos, Martyr George Righteous Maximus of Ioannina February 2014 SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT Strict fast: No = fish 19/ meat, dairy, fish, permitted 1 oil or wine All foods Righteous Oil & wine permitted except Makarios permitted meat 20/2 21/3 22/4 23/5 24/6 25/7 26/8 FIFTEENTH SUNDAY Maximus the +Apostle Martyrs Clement Righteous Xenē +Gregory the Righteous OF LUKE. -

"Lord I Call..." – Tone 4 Reader: in the Fourth Tone, Lord, I Call Upon

"Lord I Call..." – Tone 4 Reader: In the Fourth Tone, Lord, I call upon You, hear me! Lord, I call upon You, hear me! Let my prayer arise Hear me, O Lord! in Your sight as incense, Lord, I call upon You, hear me! and let the lifting up of my hands Receive the voice of my prayer, be an evening sacrifice!// when I call upon You!// Hear me, O Lord! Hear me, O Lord! Reader: (Reads text from service book) v. (10) Bring my soul out of prison, that I may give thanks to Your name! We glorify Your Resurrection on the third day, O Christ God, by always honoring Your life-creating Cross; by it You have renewed the corrupted nature of mankind, O almighty One. By it You have renewed our entrance to heaven,// for You are good and the Lover of mankind. v. (9) The righteous will surround me; for You will deal bountifully with me. You loosed the Tree's verdict of disobedience, O Savior, by being voluntarily nailed to the tree of the Cross. By descending to hell, O almighty God, You broke the bonds of death. Therefore, we adore Your Resurrection from the dead, singing in joy:// “Glory to You, O all powerful Lord!” v. (8) Out of the depths I cry to You, O Lord. Lord, hear my voice! You smashed the gates of hell, O Lord, and by Your death You demolished the kingdom of death. You delivered the human race from corruption,// granting the world life, incorruption and great mercy. -

Romans - #16 Antioch Bible Class

ROMANS - #16 ANTIOCH BIBLE CLASS LESSON TOPIC “DEARLY BELOVED” AT ROME SCRIPTURE LESSON: ROMANS 16:1-27 MEMORY VERSE; ROM. 16:16. Salute one another with an holy kiss. The churches of Christ salute you. INTRODUCTION Paul now comes to the end of a long, powerful and spiritually enlightening epistle to the Church at Rome. He has covered a broad range of relevant spiritual concerns applicable to the Roman church, but just as applicable to us today. I fear that there is so much more contained in this epistle which we have not been able to cover. Maybe, at least, our study opens our thoughts to the greater horizons contained in this marvelous letter. I have to wonder, what kind of letter would you or I be able to write to a church which we had never seen but were moved of God to love and desire to see. By being drawn nearer to Paul’s doctrine through this epistle, may we also be drawn nearer to God and to our fellow Christians in the process. This last chapter seems at first to be a long list of insignificant names of Roman Christians, picked up somewhere in the course of his many travels. Looking closer, we see that they were laborers with Paul at some time as well as kinsmen, beloved, servants and saints of God, known to Paul and very dear to him for various reasons. These individuals certainly gave him strong reasons to desire to visit the church at Rome. These people who were so dear to him had, in one form or another and at one time or another, been in Paul’s labors helping him on his journey. -

The Rock Paul's Revelations

THE FEAST DAY OF PETER AND PAUL Peter: The Rock Paul’s Revelations Feast Day of Peter and Paul June 29, 2017 Revision B GOSPEL: Matthew 16:13-19 EPISTLE: 2 Corinthians 11:21-12:9 Peter and Paul were both martyred in Rome at about the same time. Some claim they were martyred on the same day, but this is not conclusive. In the martyrologies of both East and West (The Prologue of Ochrid, and Butler’s Lives of the Saints, respectively), the Feast Day of both Peter and Paul is June 29. They were not martyred at the same location, however. Paul, being a Roman citizen (Acts 22:25-29) merited a quick death and was beheaded; Peter, who was not a Roman citizen, merited no special favor and was crucified (upside down at his request). Today’s Gospel lesson from either Matthew 16, Mark 8 or Luke 9 is used regularly in the West at about this time or in August. Today’s Epistle is also used in the West at about this time of year or just before Ash Wednesday prior to Lent. In the East, today’s Epistle lesson is also used for the 19th Sunday after Pentecost. In celebrating the lives of Peter and Paul together, we recognize that the Gospel for the circumcised was committed to Peter and that for the uncircumcised to Paul (Galatians 2:7-9). Yet there was considerable overlap and working together of Peter and Paul, especially in Antioch in the late 40’s and early 50’s AD (Galatians 2:11-15). -

Greek Orthodox Bible : New Testament

THE EASTERN - GREEK ORTHODOX BIBLE : NEW TESTAMENT Presented to Presented by Date – Occasion THE EASTERN - GREEK ORTHODOX BIBLE NEW TESTAMENT THE EASTERN / GREEK ORTHODOX BIBLE BASED ON THE SEPTUAGINT AND THE PATRIARCHAL TEXT NEW TESTAMENT ALSO KNOWN AS THE CHRISTIAN GREEK SCRIPTURES With extensive introductory and supplemental material The EOB New Testament is presented in memory of Archbishop Vsevolod of Scopelos (†2007) Ukrainian Orthodox Church of the USA Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople And in honor of His Beatitude Metropolitan Jonah Primate of the Orthodox Church in America ABBREVIATIONS AND CODES Indicates words added for clarity and accuracy but which may not [ ] be in the Greek text. For public reading, these words can be included or skipped Indicates words added for theological clarity and accuracy. For { } public reading, these words should be skipped Indicates words that may have been added in the Byzantine textual tradition for the purpose of clarification, harmonization or liturgical < > use and which are present in the PT, but which may not have been part of the original manuscripts ANF/PNF Ante-Nicene Fathers / Post-Nicene Fathers BAC Being as Communion, John Zizioulas CCC Catechism of the Catholic Church Modern “eclectic” texts or reconstructed "critical texts" (United CT Bible Societies Text (UBS) or the Nestle-Aland Text (NA)) CTC Called to Communion, Joseph Ratzinger EBC Eucharist, Bishop, Church, John Zizioulas EOB Eastern / Greek Orthodox Bible HBB His Broken Body, Laurent Cleenewerck HE Ecclesiastical History (Eusebius) (Paul Maier’s edition) KJV King James Version (sometimes called Authorized Version) Greek translation of the Old Testament known as the Septuagint LXX which is the basis for the main English text of the EOB/OT TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTORY SECTION ABBREVIATIONS AND CODES ..............................................................................