Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Editor's Foreword

Issue 9 December 2017 CONTENTS • Jeremy Loeliger on the NBL resurgence • 2017 Guest Speakers & Tours • Jake Marnie enjoying the Business of Sport • Touring Channel 9 Studios • Internship Placements • James Mottershead’s three course internship experience • Life at Fox Footy with Mitch Deken • Alex Zaia live from SEN116 studios • Mitch Wynd’s journalistic skills • Jake Morris’ time at AFL Victoria • Jay Singh using his initiative • Dale Atkins - Video Producer • Ryan Scott Giving it a Big Bash • Making a TV Sports Show • Covering the AFL International Cup • Sports Sponsorship Showcase • Singapore F1 Grand Prix under lights Sports Media Students touring the Channel 9 studios with Peter Hitchener • “That’s Good for Footy” ...and my career Editor’s Foreword By Ren Thompson As the siren sounds to end another year for the Sports New contributor Jake Marnie discusses this experiences Degrees at Holmesglen, it is important to celebrate in the new Bachelor of Sport Business. I review my some of the incredible experiences our student body experiences at the incredible Singapore Grand Prix. has enjoyed over the past few months. Hayley Williams discusses her time covering the AFL Our students were honoured to hear from NBL CEO International Cup, and we recap the Sponsorship Jeremy Loeliger about the revitalised national Showcase by our second-year students. basketball competition, our first and second In this edition we welcome guest contributor Ben year students toured the Channel 9 News studio, Gibson to share his experiences interviewing some while our second year students also completed of the biggest names in footy while working for sponsorship proposals with our VAFA club partners. -

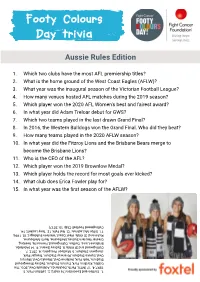

Aussie Rules Edition

Footy Colours Day trivia Aussie Rules Edition 1. Which two clubs have the most AFL premiership titles? 2. What is the home ground of the West Coast Eagles (AFLW)? 3. What year was the inaugural season of the Victorian Football League? 4. How many venues hosted AFL matches during the 2019 season? 5. Which player won the 2020 AFL Women’s best and fairest award? 6. In what year did Adam Treloar debut for GWS? 7. Which two teams played in the last drawn Grand Final? 8. In 2016, the Western Bulldogs won the Grand Final. Who did they beat? 9. How many teams played in the 2020 AFLW season? 10. In what year did the Fitzroy Lions and the Brisbane Bears merge to become the Brisbane Lions? 11. Who is the CEO of the AFL? 12. Which player won the 2019 Brownlow Medal? 13. Which player holds the record for most goals ever kicked? 14. What club does Erica Fowler play for? 15. In what year was the first season of the AFLW? Collingwood Football Club; 15. 2017) 15. Club; Football Collingwood 11. Gillon McLachlan; 12. Nat Fyfe; 13. Tony Lockett; 14. 14. Lockett; Tony 13. Fyfe; Nat 12. McLachlan; Gillon 11. Richmond, St Kilda, West Coast, Western Bulldogs); 10. 1996; 1996; 10. Bulldogs); Western Coast, West Kilda, St Richmond, Greater Western Sydney, Melbourne, North Melbourne, Melbourne, North Melbourne, Sydney, Western Greater Brisbane Lions, Carlton, Collingwood, Fremantle, Geelong, Geelong, Fremantle, Collingwood, Carlton, Lions, Brisbane Collingwood and St Kilda; 8. Sydney Swans; 9. 14 (Adelaide, (Adelaide, 14 9. Swans; Sydney 8. -

062 17-08 M1021985 Grand Final EDM.Indd

The Advertiser and Channel 7 Grand Final Lunch The Advertiser and Channel 7 is hosting Adelaide’s premier Grand Final lunch. This annual event will be at noon on Wednesday, September 27 in the William Magarey Room at Adelaide Oval. Channel 7 sports presenter MARK SODERSTROM will compere this leading event on the calendar. The golden voice of sports broadcasting DENNIS COMETTI will be the keynote speaker with tales of the behind-the-scenes moments that make the AFL grand final the biggest rating show on Australian television. Three-time Carlton premiership player and Fox Footy expert commentator MARK MACLURE will join this year’s prime line-up as a special guest. The 2017 AFL grand final will be previewed by a specialist panel including Advertiser chief football writer Michelangelo Rucci, inaugural Crows coach Graham Cornes, inaugural Crows captain Chris McDermott and Crows 199798 premiership captain Mark Bickley. The Foundation is proud to be supporting The Channel 7 Children’s Research Foundation and Inclusive Sport S.A. Generous sponsors include Channel 7, Qantas, Coopers Brewery, Lexus of Adelaide, 1882 Wines by Justin McCarthy, Central Audio Visual, Holidays of Australia & the World, Mount Franklin Coca-Cola, Hilton, Adelaide Oval Functions and Events, Keito Events, Harcourts Brock and Stallard & Potter. Tickets are $160 each and include a two-course meal and 1882 wines. Please phone Angela Condous on 8206 2344 or email [email protected] This event will sell out very quickly, so please book early to avoid disappointment. Thank you and I look forward to seeing you on the day. -

THE PEMBROKE KINGS PEMBROKE OLD SCHOLARS FOOTBALL CLUB IT’S GOOD to BE GREEN 2017 Pembrokekings.Com.Au

THE PEMBROKE KINGS PEMBROKE OLD SCHOLARS FOOTBALL CLUB IT’S GOOD TO BE GREEN 2017 pembrokekings.com.au -1- THE PEMBROKE KINGS PEMBROKE OLD SCHOLARS FOOTBALL CLUB IT’S GOOD TO BE GREEN 2017 pembrokekings.com.au -2- THE PEMBROKE KINGS PEMBROKE OLD SCHOLARS FOOTBALL CLUB IT’S GOOD TO BE GREEN 2017 pembrokekings.com.au PRESIDENTS REPORT Hi Kings Fans, Well there goes season 2017. Another year done and dusted. Last Saturday at Sacred Heart wasn’t the best end to the year. We unfortunately finished the day... and the season with 3 defeats. Seeing none of our teams in the finals for the first time in many years is tough to stomach. We always knew that the step up to Div 2 would be a tough one and losing many older and experienced heads after last years premiership added to the already difficult task. Nevertheless, we drop back down to Div 3 along with fellow college friends Scotch OC, and look forward to the 2018 season and rebuilding things on field. To add to an already tough year, the club says goodbye to both our A and B grade coaches; Jimmy Allan and Jim Pinkney. Jim is stepping aside due to an increase in family size, and therefore commitments and also work demands. Jimmy is seeking coaching opportunities at a higher level. We thank both men for their service to the Kings over the past two years in the coaching department and wish them the best of luck in the future. Jack and myself are now on the hunt for their replacements and ill leave no stone unturned in finding the right fit for the club. -

Hall of Fame

AFL | 2017-18 Annual Report 1 HALL OF FAME 2017-18 ANNUAL REPORT 2 AFL | 2017-18 Annual Report Current NTFL Premier League men’s and women’s teams at TIO Stadium AFL | 2017-18 Annual Report 3 CONTENTS CHAIRMAN’S REPORT...................................5 REMOTE PROJECTS..................................... 20 CEO’S REPORT................................................6 MICHAEL LONG LEARNING AND LEADERSHIP CENTRE (MLLLC)................... 22 AFLNT DIRECTORS.........................................8 FACILITIES.................................................... 24 EXECUTIVE TEAM....................................... 11 TALENT & PATHWAYS................................ 26 STAFF............................................................ 12 COMMERCIAL & MARKETING.................. 28 COMMUNITY FOOTBALL........................... 14 COMMUNICATIONS & DIGITAL ............... 30 GAME DEVELOPMENT & PARTICIPATION....................................... 18 FINANCIALS................................................. 32 4 AFL | 2017-18 Annual Report Cameron Ilett accepts his second Nichols Medal AFL | 2017-18 Annual Report 5 CHAIRMAN’S REPORT Welcome to the 2018 AFLNT Annual Our Remote Programs continue to produce great Report and as Chairman I take this outcomes for young Territorians and this year following a presentation by two of our remote opportunity to highlight some of the staff to the AFL Executive in Alice Springs in May, major items for the year. the team then did a further presentation to the This year commenced with a changing of the AFL staff and Commission in Melbourne. This guard at a CEO level as we welcomed back Stuart culminated with the AFL Commissioner including Totham into the fold of NT Football. Stuart has the great work of our programs in his Grand Final certainly added his home-grown flavour to the Day address promoting how programs such as position and he has remodelled and built a this assisted the AFL to deliver better outcomes strong team who deliver many AFL programs all for Australians involved in our game. -

Minutes of the 166Th Annual General Meeting of the Melbourne Cricket

MINUTES OF THE 181st ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING OF THE MELBOURNE CRICKET CLUB HELD IN THE MEMBERS DINING ROOM, M.C.G., ON WEDNESDAY 15 AUGUST 2018 AT 8PM 1 WELCOME The Chairman Mr. Steven Smith welcomed members to the Annual Meeting and formally declared the meeting open. He read out the notice of the meeting and welcome Life Members, Mr. John Cain, Mr. Bruce Church, Mr. David Meiklejohn and Mr. Bob Lloyd. He also acknowledged former members of the Committee, Mr. Stephen Spargo, Mr. Peter Mitchell and Ms. Jane Nathan. He then acknowledged Mr. Tim Wallace from Ernst and Young, the Club’s auditors and Mr. Grant Rowlands from Ashurst, legal advisors to the Club. He then acknowledged Mr. Bernie Szentirmay from KPMG, the Club’s auditors and Mr. Grant Rowlands from Ashurst, legal advisors to the Club. Introductions were given to Committee members Mr. Charles Sitch, Mr. Mark Smith, Ms. Sally Macindoe, Mr. James Bennett, Mrs Clare Cannon, Mr. Adrian Anderson, Mr. Christian Johnston, Mr. Peter King, Ms. Karen Wood (Vice President), Mr. Michael Happell (Vice President), Mr. Michael Andrew (Treasurer) , Mr. Fred Oldfield (Vice President) and Mr. Ted Baillieu. Next, he introduced CEO Mr. Stuart Fox and members of the Senior Leadership team, Mr. Scott Butler (GM - Membership and Heritage), Mr. Gerard Griffin (GM-Venue & Event Services), Mr. Clive Driscoll (GM - Finance and Business Development), Ms. Donna Price, (GM – People & Culture), Mr. Rey Sumaru (GM - IT and Innovation), Ms. Jen Watt (GM- Commercial Operations & Partnerships) and Mr. Peter Wearne (GM - Facilities), as well as Mr. Mark Anderson (Club Manager), Ms. -

1. Preliminary 2. 2017 Membership Terms And

REGULATIONS BRISBANE BEARS-FITZROY FOOTBALL CLUB LIMITED 1. PRELIMINARY 1.1 These Regulations are made by the Board of this Club pursuant to the power conferred upon the Board by Section 12 of the Constitution of the Club. 1.2 These Regulations are to be read subject to the Constitution of the Club and in the event of any inconsistency, the Constitution shall prevail. 1.3 These Regulations are binding on each member of the Club in the same manner as if each member had subscribed his/her name thereto. 1.4 In these Regulations the expression "the Club" means the registered club known as the "Brisbane Bears-Fitzroy Football Club Limited”. 1.5 In these Regulations the expression "Board" means the Board of Directors of the Club. 1.6 In these Regulations the expression “Lions@Springwood” means the Brisbane Lions Social Club located at 2 Pannikin Street Rochedale South. 1.7 In these Regulations the expression “Social Club” means the Lions@Springwood Club located at 2 Pannikin Street Rochedale South. 1.8 The interpretations mentioned in the Constitution shall apply to these Regulations. 2. 2017 MEMBERSHIP TERMS AND CONDITIONS References in these Terms and Conditions to “members” or “membership” relate to the rights and obligations attaching to packages sold by the Club for each football season unless specific reference is made to rights and obligations attaching to membership or members under the Club’s Constitution. The following table outlines the various categories of football membership and how they relate to Membership categories defined in the Club’s Constitution: Constitutional Football Membership Voting Priority Membership Categories within Rights Finals Category respective Constitutional Access Category subject to Lions participation Full Member Premium, Prime, Standard Y Y 11-game reserved seat, 11-game General Admission, Traditional Victorian & Victorian Plus adult, concession and family adults aged over 18 years old. -

THE PEMBROKE KINGS PEMBROKE OLD SCHOLARS FOOTBALL CLUB IT’S GOOD to BE GREEN 2017 Pembrokekings.Com.Au Friday August 12Th 2017 Round 17 - Scotch OC Home

THE PEMBROKE KINGS PEMBROKE OLD SCHOLARS FOOTBALL CLUB IT’S GOOD TO BE GREEN 2017 pembrokekings.com.au Friday August 12th 2017 Round 17 - Scotch OC Home -1- THE PEMBROKE KINGS PEMBROKE OLD SCHOLARS FOOTBALL CLUB IT’S GOOD TO BE GREEN 2017 pembrokekings.com.au Friday August 12th 2017 Round 17 - Scotch OC Home CONTENTS PAGE Wine Flyer ......... ……...…………………………...…………………….……………………..………….…. 3 Sponsors Day Flyer ......... ……...…………………………...…………………….……………………..… 4 End of Season Dinnner Flyer ......... ……...…………………………...…………………….…………… 5 Presidents Report …...…………………………...…………………….……………………..………….… 6 A Grade Report ……...…………………………...…………………….……………………..………….…. 7 B Grade Report ……...…………………………...…………………….……………………..………….…. 8 C Grade Report ……...…………………………...…………………….……………………..………….…. 9 A Grade Team ……...…………………………...…………………….……………………..………….…. 10 B Grade Team ……...…………………………...…………………….……………………..………….…. 11 C Grade Team ……...…………………………...…………………….……………………..………….…. 12 Games Tally ………………………………………………………………...…………………………….. 13 Player Interview ……………………………………………………………...…………………………….. 14 Footy Quiz ………………………………………………………………...…………………………….. 16 A Grade Fixture …………………………………………………………...…………………………….. 17 B Grade Fixture …………………………………………………………...…………………………….. 19 C Grade Fixture ……………………………………………………………...…………………………….. 21 Major Sponsors …………………………………………………….……………………..……………….. 23 Jumper/Short/Gold Scoreboard Sponsors …………………….……………………..……………….. 24 Gold/Bronze Sponsors …………………………………………….……………………..……………….. 25 Player Sponsors …………………………………………………….……………………..……………….. 26 Pembroke -

A Day to Remember for Richmond Fans

NOVEMBER 2017 | NO.167 | ISSN 1322-3771 MCC NewsCLUB NEWS A DAY TO REMEMBER FOR RICHMOND FANS As the Tigers ROARED to their first FLAG in 37 years. See pages 12-13. NOVEMBER 2017 MCC NEWS 1 CLUB NEWS Life membership for Paul Sheahan aul has strong ties to the MCC that go back several Three committee members – Adrian Anderson, Clare Cannon decades. A First XI premiership player, he is an MCC and Peter King – stood for re-election by rotation. Duncan PHonorary Cricket member, a XXIX Club member and in Banks, Bill Hodges Jr and John Mugavin presented themselves 2000 was selected in the MCC Team of the Century. He is also a for election via the ballot process. The results of the election Life member of the Marylebone Cricket Club. were were as follows: $QHOHJDQWULJKWKDQGEDWVPDQDQGāQHFRYHUāHOGVPDQKH played 31 Tests for Australia between 1967 and 1974, scoring 1594 CANDIDATE TOTAL VOTES runs at 33.91, including two centuries. For Victoria, he scored UXQVLQāUVWFODVVPDWFKHVDWWKHH[FHOOHQWDYHUDJHRI CANNON, Clare* 5889 59.52. He was also an MCC First XI premiership player. KING, Peter* 5528 ANDERSON, Adrian* 5519 Seemingly on the verge of becoming Australia's regular Test MUGAVIN, P. John 3638 opening batsman, Paul retired at the relatively young age of 27 HODGES, Bill Jr 1926 to concentrate on his teaching career. He eventually served as BANKS, Duncan 1413 headmaster at Melbourne Grammar School (1995-2009) after a decade as principal at Geelong College (1986-95). *retiring but seeking re-election Paul served on the MCC Committee for 28 years (1987-2015), including eight years as a vice-president and four years as As a result, Adrian Anderson, Clare Cannon and Peter King were president (2011-15). -

Afl Ticket Scheme Proposal

2017 AFL TICKET SCHEME PROPOSAL PREAMBLE The AFL Premiership Season and Finals Series attracts over 6.8 million attendees across stadia across the country, making it the most-attended sport in Australia. The 2016 AFL Finals Series drew crowds of over 550,000 patrons across various venues across the country, including crowds in the vicinity of 100,000 for the AFL Grand Final. The AFL Grand Final is recognised as Australia’s most prestigious single sporting event, attracting thousands of visitors to Melbourne each year and driving millions of dollars benefit to the local economy. The demand for AFL Grand Final tickets always outstrips supply and tickets to this event are some of the most sought after in Australian sport. The AFL Finals Series and AFL Grand Final are both very important parts of the football season, regardless of whether or not a Club has qualified. The AFL believes that given all Clubs play an active role in shaping the AFL Final Series, they should be given the opportunity to participate and with this in mind the AFL makes available AFL Grand Final tickets to them. The AFL’s fundamental role is to act as a collective for its Clubs and, after meeting the costs of running the AFL competition, make annual distributions to our clubs and annual grants to the various state bodies for the development of grass roots football. AFL’s capacity to continue to support the clubs and grass roots football in a financial sense is inextricably linked to key revenue streams and specifically the AFL Grand Final. -

1. AFLW Grand Final: the AFLW Grand Final Was Played at Metricom Stadium (Capacity 25 000), Carrara, Queensland on the Saturday 25 March

1. AFLW Grand Final: The AFLW Grand Final was played at Metricom Stadium (capacity 25 000), Carrara, Queensland on the Saturday 25 March. Adelaide scored 4 goals 11 behinds v Brisbane 4 goals 5 behinds. Which team won and by how much? Goal Behind Goal Behind Winner 4 11 4 5 Adelaide 4x6 11x1 Brisbane Winning Margin A crowd of 15 610 spectators attended the AFW Grand Final, in contrast, the Round 1 game between Brisbane and Gold Coast at the same venue only had 12 710. How many more spectators attended the AFLW than the AFL Round 1 game between Brisbane and Gold Coast? AFW Grand Final Round 1 + = 15 610 12 710 2. All teams travel throughout the year and we can use Draw a line and fill in the boxes the distance from Perth. these distances to calculate how far a team travels. The first one has been done for you. Destination from Kilometres for Ovals Perth travelling by air one way trip Perth to Melbourne 2699 km MCG Perth to Sydney 3274 km SCG Perth to Brisbane 3605 km The Gabba Perth to Adelaide 1162 km Adelaide Oval Perth to Darwin 3649 km Marrara Oval Domain Perth to Perth 0 km Stadium In Round 1 West Coast had to travel to Etihad Geelong had to travel to Domain Stadium to Stadium to play North Melbourne. How far did play Fremantle. How far did the Geelong the West Coast players have to travel in getting players have to travel in getting to and from to and from Etihad Stadium? Etihad Stadium? To To From From Total Total Distance Distance 3. -

Diversification of Revenue Streams at Australian Sporting Clubs

DIVERSIFICATION OF REVENUE STREAMS AT AUSTRALIAN SPORTING CLUBS JONATHAN HARRIS Managing Partner, ANZ BACKGROUND Over the past 12 to 18 months, many clients of SRi’s Australian and New Zealand practice have put an increasing focus on the diversification of revenue streams within club commercial operations. The extremely competitive Australian sponsorship market and ethical dilemmas surrounding pokie machines or Leagues Club distributions, have pushed the more progressive clubs and teams in Australia to seek new revenue streams in analogous and complimentary areas of business. Traditional revenue streams in clubland – those includ- ing Sponsorship, Hospitality, Membership, Merchandise and match-day – remain critical to a club’s commercial operations, of course, but these streams are increas- ingly being supplemented by a diverse array of new revenue possibilities. Jonathan Harris, Managing Partner ANZ, looks at some of the different ways in which Australian sporting clubs are innovating around their revenue opportunities, and how in turn this is impacting organisations’ hiring strategies. POOLING RESOURCES FOR PROFIT IN MULTI-SPORT MODELS Recently there have been numerous formal and informal The Adelaide Crows, for example, took sole ownership of The partnerships and acquisitions across various sport codes in Adelaide Bite in June, who are set to compete in the revamped Australia. Examples of these include relationships between Australian Baseball League for the 2018-2019 season. The part- Super Netball Teams with both AFL and NRL clubs, ABL and AFL, nered clubs recently announced they intend to leverage the NBL and AFL and Touch Football and NRL. scale and systems of Adelaide Football Club to enhance member and fan engagement, including improved content production Sharing CRM, Data and Fan Engagement Strategies amongst and distribution, game day experience and member servicing.