Arxiv:2009.07266V1 [Astro-Ph.SR] 15 Sep 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identify the Following

1. This planet appears to be lying on its side. A. Jupiter B. Saturn C. Neptune D. Uranus E. none of these 2. This planet is the hottest on the solar system. This is due to the swirling clouds pf sulfur and sulfuric acid that obscure its surface making its atmosphere heavy and dense. A. Mercury B. Venus C. Earth D. Mars E. none of these 3. The only asteroid known to have a satellite. A. Ceres B. Eris C. Makemake D. Ida E. none of these 4. It is an anticyclonic storm on Jupiter that has been existing for 180 years and it is expected to last for another 345 years. A. GDS B. GBS C. GSS D. SSS E. none of these 5. It is the second largest planet and it has spectacular rings that can be seen on Earth by telescope. A. Jupiter B. Saturn C. Neptune D. Uranus E. none of these 6. It divides the planets into Inner Planets and Outer Planets. A. Kuiper Belt B. Asteroid Belt C. Oort Cloud D. heliopause E. none of these 7. Pluto is now considered a ____. A. Giant Planet B. Dwarf Planet C. Elf Planet D. Little Solar System E. none of these 8. It is made up of many small comets orbiting around the sun. It is the area wherein scientists believed Pluto to be a part of. A. Kuiper Belt B. Asteroid Belt C. Oort Cloud D. heliopause E. none of these 9. The belt in number 8 was discovered by ___. A. Nicolaus Copernicus B. -

Astronomical Distances

The Act of Measurement I: Astronomical Distances B. F. Riley The act of measurement causes astronomical distances to adopt discrete values. When measured, the distance to the object corresponds through an inverse 5/2 power law – the Quantum/Classical connection – to a sub-Planckian mass scale on a level or sub-level of one or both of two geometric sequences, of common ratio 1/π and 1/e, that descend from the Planck mass and may derive from the geometry of a higher-dimensional spacetime. The distances themselves lie on the levels and sub-levels of two sequences, of common ratio π and e, that ascend from the Planck length. Analyses have been performed of stellar distances, the semi-major axes of the planets and planetary satellites of the Solar System and the distances measured to quasars, galaxies and gamma-ray bursts. 1 Introduction Using Planck units the Quantum/Classical connection, characterised by the equation (1) maps astronomical distances R – in previous papers only the radii of astronomical bodies [1, 2] – onto sub-Planckian mass scales m on the mass levels and sub-levels1 of two geometric sequences that descend from the Planck mass: Sequence 1 of common ratio 1/π and Sequence 3 of common ratio 1/e.2 The sequences may derive from the geometry of a higher-dimensional spacetime [3]. First, we show that several distances associated with the Alpha Centauri system correspond through (1) to the mass scales of principal levels3 in Sequences 1 and 3. We then show that the mass scales corresponding through (1) to the distances from both Alpha Centauri and the Sun to the other stars lie on the levels and sub-levels of Sequences 1 and 3. -

Abstracts of Extreme Solar Systems 4 (Reykjavik, Iceland)

Abstracts of Extreme Solar Systems 4 (Reykjavik, Iceland) American Astronomical Society August, 2019 100 — New Discoveries scope (JWST), as well as other large ground-based and space-based telescopes coming online in the next 100.01 — Review of TESS’s First Year Survey and two decades. Future Plans The status of the TESS mission as it completes its first year of survey operations in July 2019 will bere- George Ricker1 viewed. The opportunities enabled by TESS’s unique 1 Kavli Institute, MIT (Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States) lunar-resonant orbit for an extended mission lasting more than a decade will also be presented. Successfully launched in April 2018, NASA’s Tran- siting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) is well on its way to discovering thousands of exoplanets in orbit 100.02 — The Gemini Planet Imager Exoplanet Sur- around the brightest stars in the sky. During its ini- vey: Giant Planet and Brown Dwarf Demographics tial two-year survey mission, TESS will monitor more from 10-100 AU than 200,000 bright stars in the solar neighborhood at Eric Nielsen1; Robert De Rosa1; Bruce Macintosh1; a two minute cadence for drops in brightness caused Jason Wang2; Jean-Baptiste Ruffio1; Eugene Chiang3; by planetary transits. This first-ever spaceborne all- Mark Marley4; Didier Saumon5; Dmitry Savransky6; sky transit survey is identifying planets ranging in Daniel Fabrycky7; Quinn Konopacky8; Jennifer size from Earth-sized to gas giants, orbiting a wide Patience9; Vanessa Bailey10 variety of host stars, from cool M dwarfs to hot O/B 1 KIPAC, Stanford University (Stanford, California, United States) giants. 2 Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology TESS stars are typically 30–100 times brighter than (Pasadena, California, United States) those surveyed by the Kepler satellite; thus, TESS 3 Astronomy, California Institute of Technology (Pasadena, Califor- planets are proving far easier to characterize with nia, United States) follow-up observations than those from prior mis- 4 Astronomy, U.C. -

The 10 Parsec Sample in the Gaia Era?,?? C

A&A 650, A201 (2021) Astronomy https://doi.org/10.1051/0004-6361/202140985 & c C. Reylé et al. 2021 Astrophysics The 10 parsec sample in the Gaia era?,?? C. Reylé1 , K. Jardine2 , P. Fouqué3 , J. A. Caballero4 , R. L. Smart5 , and A. Sozzetti5 1 Institut UTINAM, CNRS UMR6213, Univ. Bourgogne Franche-Comté, OSU THETA Franche-Comté-Bourgogne, Observatoire de Besançon, BP 1615, 25010 Besançon Cedex, France e-mail: [email protected] 2 Radagast Solutions, Simon Vestdijkpad 24, 2321 WD Leiden, The Netherlands 3 IRAP, Université de Toulouse, CNRS, 14 av. E. Belin, 31400 Toulouse, France 4 Centro de Astrobiología (CSIC-INTA), ESAC, Camino bajo del castillo s/n, 28692 Villanueva de la Cañada, Madrid, Spain 5 INAF – Osservatorio Astrofisico di Torino, Via Osservatorio 20, 10025 Pino Torinese (TO), Italy Received 2 April 2021 / Accepted 23 April 2021 ABSTRACT Context. The nearest stars provide a fundamental constraint for our understanding of stellar physics and the Galaxy. The nearby sample serves as an anchor where all objects can be seen and understood with precise data. This work is triggered by the most recent data release of the astrometric space mission Gaia and uses its unprecedented high precision parallax measurements to review the census of objects within 10 pc. Aims. The first aim of this work was to compile all stars and brown dwarfs within 10 pc observable by Gaia and compare it with the Gaia Catalogue of Nearby Stars as a quality assurance test. We complement the list to get a full 10 pc census, including bright stars, brown dwarfs, and exoplanets. -

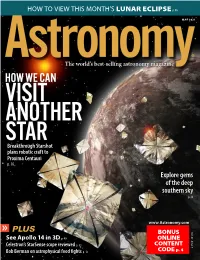

Breakthrough Starshot Plans Robotic Craft to Proxima Centauri P

HOW TO VIEW THIS MONTH’S LUNAR ECLIPSE p. 46 MAY 2021 The world’s best-selling astronomy magazine Breakthrough Starshot plans robotic craft to Proxima Centauri p. 16 Explore gems of the deep southern sky p. 48 www.Astronomy.com PLUS V BONUS o l . 4 9 p. 40 ONLINE • See Apollo 14 in 3D I s s u CONTENT e p. 54 Celestron’s StarSense scope reviewed 5 CODE p. 4 Bob Berman on astrophysical food fights p. 13 Breakthrough A voyage to the stars Using laser-propelled lightsails, tiny spacecraft could venture to the Sun’s nearest neighbor in just a few decades. BY JAKE PARKS n Nov. 6, 2018, as millions of telescope at Haleakalā Observatory in Americans cast their votes in a Hawaii. But it wasn’t until he began explor- hotly contested midterm elec- ing what he himself describes in his book tion, astrophysicist Avi Loeb as “an exotic hypothesis, without question” sat in his office surrounded that he began to take it seriously — if only Oby four television crews. Loeb, as a thought experiment. chair of Harvard University’s Department He drew his ‘Oumuamua hypothesis of Astronomy and author of the new from what was fresh in his mind. At that book Extraterrestrial (Houghton Mifflin point, Loeb had spent the previous few years Harcourt, 2021), was not being targeted working with some of the world’s brightest for his political insight. and most ambitious people quiry “A tantalizing, probing in fe.” he possibilities of alien li into t views Instead, the media atten- — Kirkus Re to develop an audacious e tion was due to his recent x interstellar mission that t eye-catching paper r would use lightsails to a t exploring whether the e venture to a nearby star. -

Jeu Complet Recto

$* ) & !'! # 6 0 < ! 7* )) 4 4 $* & " * : * @ 1 * * 0* 4 ? * ) ) : 7 6 ! ! * 6! * ! *" ( 7 * ! # ! 0A * ) 8 0 ! $ ! ( ) ! & 8 B/CCD;EF/ GDC/<F6H;/C # & # ) 6 ID;5D;7 ! /*I * ; 8 4<J9 ' * '! ! ' +,-."/ + # , * $ ! ! * * ! " ! " #!$!% & '#!$!%! 7** ! # $ ! - % ! * ' !'.; ) &&$ ' ' 4 ! 5 & ' ' :)) * ( '' * 7 < #% ' ' * #) * + = ,- ) . 0 ! 4 < / ) ) $ * 8 3> $ 0* 01##'2 '- 0. 3'2 0 ) 1 )' -$ . % '45' -! . '5' -! '2 ' 0 . ) * ! !" '2)' 0 0 6 * $ * ! * 7 $ '45' * 0 )) * ! / * '5' ! ? ! * ! 1 ! / 0 * ! 0 8 * ) ! )) * #!% ! 9 * 6 * )) 1 ! ! # ) / * ) 0 * ! ) @ 0 9 ! 0 0 ! " )* 6 -

Vanderbilt University, Department of Physics & Astronomy 6301

CURRICULUM VITAE: KEIVAN GUADALUPE STASSUN Vanderbilt University, Department of Physics & Astronomy 6301 Stevenson Center Ln., Nashville, TN 37235 Phone: 615-322-2828, FAX: 615-343-7263 [email protected] DEGREES EARNED University of Wisconsin—Madison Degree: Ph.D. in Astronomy, 2000 Thesis: Rotation, Accretion, and Circumstellar Disks among Low-Mass Pre-Main-Sequence Stars Advisor: Robert D. Mathieu University of California at Berkeley Degree: A.B. in Physics/Astronomy (double major) with Honors, 1994 Thesis: A Simultaneous Photometric and Spectroscopic Variability Study of Classical T Tauri Stars Advisor: Gibor Basri EMPLOYMENT HISTORY Vanderbilt University Founder and Director, Frist Center for Autism & Innovation, 2018-present Professor of Computer Science, School of Engineering, 2018-present Stevenson Endowed Professor of Physics & Astronomy, College of Arts & Science, 2016-present Senior Associate Dean for Graduate Education & Research, College of Arts & Science, 2015-18 Harvie Branscomb Distinguished Professor, 2015-16 Professor of Physics and Astronomy, 2011-16 Director, Vanderbilt Initiative in Data-intensive Astrophysics (VIDA), 2007-present Founder and Director, Fisk-Vanderbilt Masters-to-PhD Bridge Program, 2004-15 Associate Professor of Physics and Astronomy, 2008-11 Assistant Professor of Physics and Astronomy, 2003-08 Fisk University Adjoint Professor of Physics, 2006-present University of Wisconsin—Madison NASA Hubble Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Astronomy, 2001-03 Area: Observational Studies of Low-Mass Star -

Ebook Download Proxima Centauri Ebook Free Download

PROXIMA CENTAURI PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Farel Dalrymple | 160 pages | 29 Jan 2019 | Image Comics | 9781534310292 | English | Fullerton, United States Proxima Centauri PDF Book Proxima Centauri by admin July 6, August 30, Terrestrial sources will also have to be ruled out, along with orbiting satellites, as Seth Shostak, senior scientist with the SETI institute, explained in a recent post :. It is possible there are other planets, slightly further from the star, that have yet to be discovered by astronomers, but they are likely too far away for liquid water to form. To illustrate what this means from our perspective: the Voyager 1 spacecraft is currently travelling away from Earth at a speed of The Planetary Science Journal Tag: Science. It was discovered by the Scottish astronomer Robert Innes in Except… in August astronomers announced they had confirmed the presence of a planet orbiting the diminutive star , and moreover it's very roughly the same mass as Earth , orbiting Proxima in its habitable zone. It's very hard to measure, because the shift is very small, and Proxima is very faint. Extended Data Table 1 Complete set of model parameters Full size table. To view the star, one needs a telescope with an aperture of at least 3. Kopparapu, R. According to Star Trek: Star Charts pp. When the star approaches the Earth in that little circle the wavelength of its light gets a little bit shorter we call that blushift , and when it heads away in the other half of its circle the wavelength gets longer redshift ; this is similar to the Doppler shift in sound. -

Survival of Exomoons Around Exoplanets 2

Survival of exomoons around exoplanets V. Dobos1,2,3, S. Charnoz4,A.Pal´ 2, A. Roque-Bernard4 and Gy. M. Szabo´ 3,5 1 Kapteyn Astronomical Institute, University of Groningen, 9747 AD, Landleven 12, Groningen, The Netherlands 2 Konkoly Thege Mikl´os Astronomical Institute, Research Centre for Astronomy and Earth Sciences, E¨otv¨os Lor´and Research Network (ELKH), 1121, Konkoly Thege Mikl´os ´ut 15-17, Budapest, Hungary 3 MTA-ELTE Exoplanet Research Group, 9700, Szent Imre h. u. 112, Szombathely, Hungary 4 Universit´ede Paris, Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris, CNRS, F-75005 Paris, France 5 ELTE E¨otv¨os Lor´and University, Gothard Astrophysical Observatory, Szombathely, Szent Imre h. u. 112, Hungary E-mail: [email protected] January 2020 Abstract. Despite numerous attempts, no exomoon has firmly been confirmed to date. New missions like CHEOPS aim to characterize previously detected exoplanets, and potentially to discover exomoons. In order to optimize search strategies, we need to determine those planets which are the most likely to host moons. We investigate the tidal evolution of hypothetical moon orbits in systems consisting of a star, one planet and one test moon. We study a few specific cases with ten billion years integration time where the evolution of moon orbits follows one of these three scenarios: (1) “locking”, in which the moon has a stable orbit on a long time scale (& 109 years); (2) “escape scenario” where the moon leaves the planet’s gravitational domain; and (3) “disruption scenario”, in which the moon migrates inwards until it reaches the Roche lobe and becomes disrupted by strong tidal forces. -

Instrumentation for the Detection and Characterization of Exoplanets

Instrumentation for the detection and characterization of exoplanets Francesco Pepe1, David Ehrenreich1, Michael R. Meyer2 1Observatoire Astronomique de l'Université de Genève, 51 ch. des Maillettes, 1290 Versoix, Switzerland 2Swiss Federal Institute of Technology, Institute for Astronomy, Wolfgang-Pauli-Strasse 27, 8093 Zurich, Switzerland In no other field of astrophysics has the impact of new instrumentation been as substantial as in the domain of exoplanets. Before 1995 our knowledge about exoplanets was mainly based on philosophical and theoretical considerations. The following years have been marked, instead, by surprising discoveries made possible by high-precision instruments. More recently the availability of new techniques moved the focus from detection to the characterization of exoplanets. Next- generation facilities will produce even more complementary data that will lead to a comprehensive view of exoplanet characteristics and, by comparison with theoretical models, to a better understanding of planet formation. Astrometry is the most ancient technique of astronomy. It is therefore not surprising that the first (unconfirmed) detection of an extra-solar planet arose through this technique1. In 1984, another detection of a planetary-mass object around the nearby star VB 8 was claimed, this time using speckle interferometry2, but subsequent attempts to locate it were unsuccessful. It was finally Doppler velocimetry that delivered the first unambiguous detection of a probable brown dwarf around HD 1147623. In 1992, a handful of bodies of terrestrial mass were found4 and confirmed, by the measurement of timing variation, to orbit the pulsar PSR1257+12. Although very powerful, this technique was restricted to a small number of very particular hosts. -

The Ancient Eurasian World and the Celestial Pivot

SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS Number 192 September, 2009 In and Outside the Square: The Sky and the Power of Belief in Ancient China and the World, c. 4500 BC – AD 200 Volume I: The Ancient Eurasian World and the Celestial Pivot by John C. Didier Victor H. Mair, Editor Sino-Platonic Papers Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, PA 19104-6305 USA [email protected] www.sino-platonic.org SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS is an occasional series edited by Victor H. Mair. The purpose of the series is to make available to specialists and the interested public the results of research that, because of its unconventional or controversial nature, might otherwise go unpublished. The editor actively encourages younger, not yet well established, scholars and independent authors to submit manuscripts for consideration. Contributions in any of the major scholarly languages of the world, including Romanized Modern Standard Mandarin (MSM) and Japanese, are acceptable. In special circumstances, papers written in one of the Sinitic topolects (fangyan) may be considered for publication. Although the chief focus of Sino-Platonic Papers is on the intercultural relations of China with other peoples, challenging and creative studies on a wide variety of philological subjects will be entertained. This series is not the place for safe, sober, and stodgy presentations. Sino-Platonic Papers prefers lively work that, while taking reasonable risks to advance the field, capitalizes on brilliant new insights into the development of civilization. The only style-sheet we honor is that of consistency. Where possible, we prefer the usages of the Journal of Asian Studies. -

Infinite Worlds

Infinite Worlds Twinkle satellite Credit UCL The e-magazine of the Exoplanets Division Of the Asteroids and Remote Planets Section Issue 7 2020 July 1 Contents Section officers News Meetings Discoveries – latest news Web sites of interest Publications Astrobiology Pro-am projects - ARIEL - Twinkle Space – Stepping stones to other star systems Section officers ARPS Section Director Dr Richard Miles Assistant Director (Astrometry) Peter Birtwhistle Assistant Director (Occultations) Tim Haymes Assistant Director (Exoplanets) Roger Dymock Exoplanet Technical Advisory Group (ETAG) Peta Bosley, Simon Downs, Steve Futcher, Paul Leyland, David Pulley, Mark Salisbury, Americo Watkins News The Blue Marble. The first full-view photograph of the planet, was taken by Apollo 17 astronauts en route to the Moon in 1972. We haven’t, as yet, found anywhere else like it in our galaxy. When we do, let us hope it is virus-free!!! 2 ASTERIA spacecraft This mission was recently in the news for being the smallest telescope to detect an exoplanet – 55 Cancri-e. Demonstrating high-precision photometry with a CubeSat: ASTERIA observations of 55 Cancri e Observations made with the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope (ESO’s VLT) have revealed the tell-tale signs of a planetary system being born. Meetings 2020 Sagan Summer Virtual Workshop: Extreme Precision Radial Velocity - https://nexsci.caltech.edu/workshop/2020/ EuroPlanet Science Congress 21 Sep – 9 Oct - https://www.epsc2020.eu/ This is a virtual meeting and Mark Salisbury and Martin Crow will be participating in the main conference and Splinter sessions wrt the ARIEL mission and ExoClock project. PLATO Week 11 meeting (probably October, date tba).