Hess Bit Player Ab I-Xvi 1-192.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Tragedy of Transportation: Underfunding Our Future Richard Ravitch Former Lieutenant Governor, New York

The Alan M. Voorhees Transportation Center and the Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy present THE ALAN M. VOORHEES DISTINGUISHED LECTURE Monday, November 11, 2013, 5:00 p.m. Special Events Forum, Civic Square Building The Tragedy of Transportation: Underfunding our Future Richard Ravitch Former Lieutenant Governor, New York Richard Ravitch is a lawyer, businessman, and public official who has been engaged in private and public business for more than 50 years. Mr. Ravitch is drawn to public service as a lifelong New Yorker. Educated at Columbia College and Yale Law School, he has become known as “Mr Fix-It” because of his “renaissance man” abilities to problem solve difficult problems. In 2012, he co-chaired the New York State Budget Crisis Task Force. He served as Lieutenant Governor of the State of New York from 2009 to 2010. Prior to his appointment as Lieutenant Governor, Mr. Ravitch served as chairman of the New York State Urban Development Corporation, the Bowery Savings Bank, HRH Construction Corporation, and AFL-CIO Housing Investment Trust. He also was called upon by Major League Baseball to negotiate a labor agreement on behalf of the owners. Mr. Ravitch was also selected by Governor Hugh Carey to lead the Metropolitan Transportation Authority in 1979 during the agency’s most troubled time. He is widely credited as having been the catalyst for the restoration of the MTA in subsequent years. A reception will follow the lecture. Please RSVP by Friday, November 1 to Stephanie Kose by phone at 848-932-2832 or by e-mail to [email protected]. -

APPENDICES Appendix A. University of Minnesota Presidents

AppendixAppendices 133 APPENDICES Appendix A. University of Minnesota Presidents ................................... 135 Appendix B. College of Pharmacy Deans ...............................................139 Appendix C. Medicinal Chemistry Department Heads .......................... 141 Appendix D. Outstanding Achievement Awards ....................................143 Appendix E. Books Authored by Medicinal Chemistry Faculty ...............149 Appendix F. Graduates of the Department of Medicinal Chemistry ....... 151 Appendix G. Works Cited ...................................................................... 157 134 From Digitalis to Ziagen: The University of Minnesota’s Department of Medicinal Chemistry Appendix A 135 Appendix A. University of Minnesota Presidents William Watts Folwell Cyrus Northrup 1869-1884 1884-1911 George E. Vincent Marion L. Burton 1911-1917 1917-1920 136 From Digitalis to Ziagen: The University of Minnesota’s Department of Medicinal Chemistry Lotus D. Coffman Guy Stanton Ford 1920-1938 1938-1941 Walter C. Coffey James Lewis Morrill 1941-1945 1945-1960 Appendix A 137 O. Meredith Wilson Malcolm Moos 1960-1967 1967-1974 C. Peter McGrath Kenneth H. Keller 1974-1984 1985-1988 138 From Digitalis to Ziagen: The University of Minnesota’s Department of Medicinal Chemistry Nils Hasselmo Mark G. Yudof 1989-1997 1997-2002 Robert H. Bruininks Eric W. Kaler 2003-2011 2011-present Appendix B 139 Appendix B. College of PharMaCy deans Frederick J. Wulling Charles H. Rogers 1892-1936 1936-1956 George P. Hager Lawrence C. Weaver 1957-1966 1966-1984 140 From Digitalis to Ziagen: The University of Minnesota’s Department of Medicinal Chemistry Gilbert S. Banker Marilyn K. Speedie 1985-1992 1996-present Appendix C 141 Appendix C. MediCINAL CheMISTRY dePARTMent heads Glenn L. Jenkins Ole Gisvold 1936-1941 1941-1969 Taito Soine Mahmoud M. -

Robert J. Dole

Robert J. Dole U.S. SENATOR FROM KANSAS TRIBUTES IN THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES E PL UR UM IB N U U S HON. ROBERT J. DOLE ÷ 1961±1996 [1] [2] S. Doc. 104±19 Tributes Delivered in Congress Robert J. Dole United States Congressman 1961±1969 United States Senator 1969±1996 ÷ U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1996 [ iii ] Compiled under the direction of the Secretary of the Senate by the Office of Printing Services [ iv ] CONTENTS Page Biography .................................................................................................. ix Proceedings in the Senate: Prayer by the Senate Chaplain Dr. Lloyd John Ogilvie ................ 2 Tributes by Senators: Abraham, Spencer, of Michigan ................................................ 104 Ashcroft, John, of Missouri ....................................................... 28 Bond, Christopher S., of Missouri ............................................. 35 Bradley, Bill, of New Jersey ...................................................... 43 Byrd, Robert C., of West Virginia ............................................. 45 Campbell, Ben Nighthorse, of Colorado ................................... 14 Chafee, John H., of Rhode Island ............................................. 19 Coats, Dan, of Indiana ............................................................... 84 Cochran, Thad, of Mississippi ................................................... 3 Cohen, William S., of Maine ..................................................... 79 Coverdell, Paul, of Georgia ....................................................... -

C017 Roll1 115 (PDF)

This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas. http://dolearchives.ku.edu WASHINGTON (AP) .. -, · In ~ - ~City Ill~" . • The humor ,c~ natunlly Dill•, In Carbondale, m.,. In .. Ford wanteit lo stop' thell! lo Dole. 'lbereclo no'Jok, wrller · Utlle'- Rock;1Ark.,. ln the IIDAil anef the comenUon but hb m hll lUff. He, ~~..,.: ,J1 toWti .!Ueeilne,rC'IGns:j>aiided In sWr·••-dlibloua'aboutl.lneb· lhe fllnnlel& ~~ t9l Q9P , . I -~ llntt:*tlon· NStlc- and· bl'g city InC a natiCI!'Il··ciaaipliiD ~ ft.nietlqD~ and tei!Sis ID'Ierl~a , bllllrooms wtlll ch111dellen'lg. Rualll, DOle Ald.' 'lbe staff cllllpaJF IIJI.!IIi!!bs"lo-be llat.\.. (, 0\ Utter, Sen. Bob Dole -'thw.,t - In Ru..O . )acly c1111~ people, ·• JW.'Je8ds i~l)a -¥' ~. l for the •lei! presidency, wllh . couldn't flt mady oo a~eh miiiiiCIB ·tp,tiiDe, flln~ 1'- so · -..1 ; quips. • 'short notice, Dole .Ald. · poorly"'lh.J.t': ..~ . 'lit - on ~ "I'm not used tO crowds like '"lbk'.w• on a ,'lb!l.,diiY and,,, . their· barii!L ·, And · th ~· lea· re- ! lhla, I'm a Republican," says 1 aunnlled" that Friday arte... ·' spcpiwe·· lhe .. ..dllbce. · Jiie . Dole to a lhousand people plh·. noon ID lbl-.11' will a pretty . womev ~-. hli - ~~'&./: . ' ... ered to hear htn In a San ~ day for prelldaita lo stop But ·he ·u- his tbumor 1o Franelaco hotel: "But I'm !!lad ln. Moat of lhe Important meet. millie pollticll polnta • I I soni8 I lo be bell! - Republicans 1ft! '' lnp were 1'8EIIeduled - .nd... u' . Jj' ,, ' .,!"'- ~ad: ti> · be anywhere:" othem were fo~tten about," . -

The Presidential Campaign of 1936 in Indiana

Editors, Whistle Stops, and Elephants: The Presidential Campaign of 1936 in Indiana James Philip Fadely* Indiana played a prominent role in the presidential campaign of 1936 between Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt and Republican Alfred M. Landon. In an election marked by major party realign- ment, both candidates considered the Hoosier state crucial to their chances for victory. The Great Depression had stirred up politi- cians and voters, and the election of 1936 provided the occasion for FDR to defend his New Deal for the first time and for Kansas gov- ernor Landon to fashion the first Republican response to it. The Hoosier connection to the national campaign derived from Indi- ana’s electoral importance and status as a borderline state in the political battles of the 1930s. The presidential contest of 1936 in Indiana was characterized by the substantial influence of newspa- per editors, by campaign whistle stops along the railroads to bring the candidates close to the people, and by the old-fashioned excite- ment of politics evident in colorful parades and political symbols. The politicking of Eugene C. Pulliam illustrates the important role of newspapermen in the presidential campaign of 1936. Pul- liam did not yet own the two Indianapolis newspapers, the Star and the News,which he would purchase in 1944 and 1946 respec- tively, but he was building his publishing business with papers in Lebanon, Huntington, and Vincennes, Indiana, and in several small towns in Oklahoma. In 1936 the Indianapolis News was owned by the children of former Vice-president and Senator Charles W. Fair- banks and was run by son Warren C. -

FY13 Annual Report View Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2012–13 3 Introduction 5 Metropolitan Opera Board of Directors 7 2012–13 Season Repertory & Events 14 2012–13 Artist Roster 15 The Financial Results 46 Patrons Introduction The Metropolitan Opera’s 2012–13 season featured an extraordinary number of artistic highlights, earning high praise for new productions, while the company nevertheless faced new financial challenges. The Met presented seven new stagings during the 2012–13 season, including the Met premieres of Thomas Adès’s The Tempest and Donizetti’s Maria Stuarda, the second of the composer’s trilogy of Tudor operas (with the third installment planned for a future season). All seven new productions, plus five revivals, were presented in movie theaters around the world as part of the Met’s groundbreaking Live in HD series, which continued to be an important revenue source for the Met, earning $28 million. Combined earned revenue for the Met (Live in HD and box office) totaled $117.3 million. This figure was lower than anticipated as the company continued to face a flat box office, complicated by the effects of Hurricane Sandy, the aftermath of which had a negative impact of approximately $2 million. As always, the season featured the talents of the world’s leading singers, conductors, directors, designers, choreographers, and video artists. Two directors made stunning company debuts: François Girard, with his mesmerizing production of Parsifal on the occasion of Wagner’s bicentennial, and Michael Mayer, whose bold reimagining of Verdi’s Rigoletto in 1960 Las Vegas was the talk of the opera world and beyond. Robert Lepage returned to direct the highly anticipated company premiere of Thomas Adès’s The Tempest, with the composer on the podium. -

CPY Document

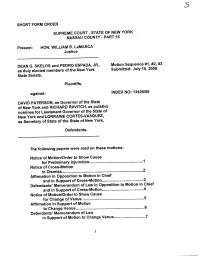

................... ........ .......... ... SHORT FORM ORDER SUPREME COURT - STATE OF NEW YORK NASSAU COUNTY - PART 15 Present: HON. WILLIAM R. LaMARCA Justice DEAN G. SKELOS and PEDRO ESPADA, JR., Motion Sequence #1, #2, #3 15, 2009 as duly elected members of the New York Submitted: July State Senate, Plaintiffs, -against- INDEX NO: 13426/09 DAVID PATERSON, as Governor of the State of New York and RICHARD RAVITCH, as putative nominee for Lieutenant Governor of the State of New York and LORRAINE CORTES-VASQUEZ, as Secretary of State of the State of New York, Defendants. The following papers were read on these motions: Notice of Motion/Order to Show Cause for Prelim inary Injunction.... Notice of Cross-Motion to Cis miss.......................................................................... Affrmation in Opposition to Motion in Chief and in Support of Cross-Motion............................. Defendants' Memorandum of Law in Opposition to Motion in Chief and in Support of Cross-Motion............................... Notice of Motion/Order to Show Cause for Change of Venue ........................................................ Affrmation in Support of Motion to Change V en ue......................... ........ .......... ....... Defendants' Memorandum of Law in Support of Motion to Change Venue......................... ............................................................................. ... Affirmations in Opposition to Cross-Motion and Motion to Change Venue.................................... Affidavit of Daniel Shapi ro.............. -

MOYNIHAN STATION PROJECT SEMINAR and TOUR Tuesday, April 29, 2014 | 8:00 AM – 10:00 AM

THE GREATER NEW YORK CONSTRUCTION USER COUNCIL PRESENTS MOYNIHAN STATION PROJECT SEMINAR AND TOUR Tuesday, April 29, 2014 | 8:00 AM – 10:00 AM JAMES A. FARLEY BUILDING Enter at North West Corner of 31st Street and 8th Avenue New York, NY The Moynihan Station Project will redevelop the landmarked James A. Farley Post Office Building into the new Manhattan home for Amtrak, transforming a treasured building into an iconic railroad passenger station and mixed-use development befitting New York City. In May 2012, MSDC awarded a $147,750,000 construction contract to Skanska USA Civil Northeast for the West End Concourse Expansion. Construction on the West End Concourse Expansion began in September 2012 with the first weekend closures of individual Penn Station tracks and platforms in order to facilitate surveying, the relocation of utilities, and preliminary foundation work for the new concourse. This type of work will continue until mid-2014 when the technically challenging steel erection phase will begin. In September 2012, the Federal Railroad Administration awarded Moynihan Station a $30 million High Speed Rail Grant through the New York State Department of Transportation for the Connecting Corridor construction and the first portion of the new Emergency Ventilation System. This event will feature a panel discussion with key project stakeholders from Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, the Port Authority of New York & New Jersey and the Moynihan Station Development Corporation. A short tour of the project site will follow the panel discussion. SPEAKERS MICHAEL J. EVANS | PRESIDENT | MOYNIHAN STATION DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION Michael Evans serves under New York State Governor Andrew Cuomo as President of the Moynihan Station Development Corporation, the New York State public authority charged with building a new intercity passenger rail station for New York City within the landmarked James A Farley Post Office Building. -

Government, Law and Policy Journal

NYSBA SUMMER 2011 | Vol. 13 | No. 1 Government, Law and Policy Journal A Publication of the New York State Bar Association Committee on Attorneys in Public Service, produced in cooperation with the Government Law Center at Albany Law School NNewew YYorkork SState’state’s BBudget:udget: CConflictsonflicts aandnd CChallengeshallenges In Memoriam Governor Hugh L. Carey 1919-2011 The Committee on Attorneys in Public Service dedicates this issue to the enduring memory of Governor Hugh L. Carey and his enumerable contributions to public service This photograph, which is entitled Governor Carey Briefs the Press on the Budget, was made available from the New York State Archives. SUMMER 2011 | VOL. 13 | NO. 1 Government, Law and Policy Journal Contents Board of Editors 2 Message from the Chair J. Stephen Casscles Peter S. Loomis Lisa F. Grumet 3 Editor’s Foreword James F. Horan Rose Mary K. Bailly Barbara F. Smith 4 Guest Editor’s Foreword Patricia K. Wood Abraham M. Lackman Staff Liaison 5 Legal History of the New York State Budget Albany Law School David S. Liebschutz and Mitchell J. Pawluk Editorial Board 11 Pataki v. Assembly: The Unanswered Question Rose Mary K. Bailly Hon. James M. McGuire Editor-in-Chief 17 New York State School Finance Patricia E. Salkin Shawn MacKinnon Director, Government Law Center 24 CFE v. State of New York: Past, Present and Future Michael A. Rebell Vincent M. Bonventre Founding Editor-in-Chief 31 Changing the Terms of New York State’s Budget Conversation Richard Ravitch Student Editors 35 New York’s Economy: From Stagnation to Decline Robert Barrows Abraham M. -

Fireside Chats”

Becoming “The Great Arsenal of Democracy”: A Rhetorical Analysis of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Pre-War “Fireside Chats” A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Allison M. Prasch IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS Under the direction of Dr. Karlyn Kohrs Campbell December 2011 © Allison M. Prasch 2011 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We are like dwarfs standing upon the shoulders of giants, and so able to see more and see further . - Bernard of Chartres My parents, Ben and Rochelle Platter, encouraged a love of learning and intellectual curiosity from an early age. They enthusiastically supported my goals and dreams, whether that meant driving to Hillsdale, Michigan, in the dead of winter or moving me to Washington, D.C., during my junior year of college. They have continued to show this same encouragement and support during graduate school, and I am blessed to be their daughter. My in-laws, Greg and Sue Prasch, have welcomed me into their family as their own daughter. I am grateful to call them friends. During my undergraduate education, Dr. Brad Birzer was a terrific advisor, mentor, and friend. Dr. Kirstin Kiledal challenged me to pursue my interest in rhetoric and cheered me on through the graduate school application process. Without their example and encouragement, this project would not exist. The University of Minnesota Department of Communication Studies and the Council of Graduate Students provided generous funding for a summer research trip to the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library in Hyde Park, New York. -

Fight for the Right: the Quest for Republican Identity in the Postwar Period

FIGHT FOR THE RIGHT: THE QUEST FOR REPUBLICAN IDENTITY IN THE POSTWAR PERIOD By MICHAEL D. BOWEN A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2006 Copyright 2006 by Michael D. Bowen ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project is the culmination of many years of hard work and dedication, but it would not have been possible without assistance and support from a number of individuals along the way. First and foremost, I have to thank God and my parents for all that they have done for me since before I arrived at the University of Florida. Dr. Brian Ward, whose admiration for West Ham United is only surpassed by his love for the band Gov’t Mule, was everything I could have asked for in an advisor. Dr. Charles Montgomery pushed and prodded me to turn this project from a narrow study of the GOP to a work that advances our understanding of postwar America. Dr. Robert Zieger was a judicious editor whose suggestions greatly improved my writing at every step of the way. Drs. George Esenwein and Daniel Smith gave very helpful criticism in the later stages of the project and helped make the dissertation more accessible. I would also like to thank my fellow graduate students in the Department of History, especially the rest of “Brian Ward’s Claret and Blue Army,” for helping make the basement of Keene-Flint into a collegial place and improving my scholarship through debate and discussion. -

Franklin Roosevelt, Thomas Dewey and the Wartime Presidential Campaign of 1944

POLITICS AS USUAL: FRANKLIN ROOSEVELT, THOMAS DEWEY, AND THE WARTIME PRESIDENTIAL CAMPAIGN OF 1944 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. POLITICS AS USUAL: FRANKLIN ROOSEVELT, THOMAS DEWEY AND THE WARTIME PRESIDENTIAL CAMPAIGN OF 1944 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Michael A. Davis, B.A., M.A. University of Central Arkansas, 1993 University of Central Arkansas, 1994 December 2005 University of Arkansas Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the U.S. wartime presidential campaign of 1944. In 1944, the United States was at war with the Axis Powers of World War II, and Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt, already serving an unprecedented third term as President of the United States, was seeking a fourth. Roosevelt was a very able politician and-combined with his successful performance as wartime commander-in-chief-- waged an effective, and ultimately successful, reelection campaign. Republicans, meanwhile, rallied behind New York Governor Thomas E. Dewey. Dewey emerged as leader of the GOP at a critical time. Since the coming of the Great Depression -for which Republicans were blamed-the party had suffered a series of political setbacks. Republicans were demoralized, and by the early 1940s, divided into two general national factions: Robert Taft conservatives and Wendell WiIlkie "liberals." Believing his party's chances of victory over the skilled and wily commander-in-chiefto be slim, Dewey nevertheless committed himself to wage a competent and centrist campaign, to hold the Republican Party together, and to transform it into a relevant alternative within the postwar New Deal political order.