New York Supreme Court APPELLATE DIVISION — SECOND DEPARTMENT >> > > Case No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Who Was Who II of Hanover, IL

1 Who Was Who II of Hanover, IL as of April 7, 2011 This proposed book contains biographies of people from Hanover who died after March 2, 1980, and up until when the book will go to the printer, hopefully in February 2011. The first Who Was Who was a book of biographies of everyone from Hanover, who had died, from the first settlers, up until February 28, 1980, when the book went to the printer. PLEASE let me know ALL middle names of everyone in each bio. This will help people doing research years from now. As you read through the information below PLEASE let me know of any omissions or corrections of any of your friends or family. I want this to be a book that will honor all of our past Hanover residents and to keep them alive in our memory. The prerequisites for being listed in this book are (1) being deceased, (2) having some sort of connection to Hanover, whether that is being born in Hanover or living in Hanover for some time, or (3) being buried in one of the three cemeteries. THANKS, Terry Miller PLEASE make sure that your friend’s and family’s biographies contain all the information listed below: 1. Date of birth 2. Where they were born 3. Parent’s name (including Mother’s maiden name) 4. Where they went to school 5. If they served in the Military – what branch – what years served 6. Married to whom, when and where 7. Name of children (oldest to youngest) 8. Main type of work 9. -

1909 Canandaigua City Directory

CentralMark Librarys Shoof Rochestere Store and Monroe, 8County6 Mai · Miscellaneousn St. DirectoriesSouth Get a Gas Range CO OS Use Electric Power The Established m Good Clothes 1869 9m Store Canandaigua. to fcatoriDi THE FINEST MAKES IN THE WORLD. SIMMONS, Rr hxaM Store 974.786 S651c 1909/10 >lies Fine Candy s? THE LAIOfSr BOOK AND 18 3TO»E BETWEEN NEW YOU AND CHICAOO j POWERS BUIL Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Miscellaneous Directories R. H. MGKERR CUT FLOWERS OF ALL KINDS IN SEASON BEDDING PLANTS PALMS AND FERNS FLORAL DESIGNS AND DECORATIONS OUR FANCY CARNATIONS ARE LEADERS Greenhouses: 33 Dailey Ave., Canandaigua, N. Y. BOTH PHONES. % WHEN YOU I THINK OF A TELEPHONE 1 LOOK FOR THE SHIELD JjJ Ontario County Has 5,000 Telephones *T The Interlake Telephone Co. Connects with these over its own metallic toll lines. Connecting ^ toll lines give service to long distance points. 1 ^00 8Ukscribers, local and rural, leaves little to be desired L WHEN YOU THINK OF A TELEPHONE. Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Miscellaneous Directories 3 9077 03643 9324 GEO. E. WOOD & SONS EDGE WATER MILK AND CREAM The best you can buy in the world Large or small orders promptly filled BOTH 'PHONES CANANDAIGUA, N. Y. W. G. LAPHAM CIGARS and TOBACCO NEWS STAND Sunday and Daily Papers Delivered to All Parts of the City. FRUITS AND CONFECTIONS First Door North of McKechnie Bank. Central Library of Rochester and Monroe County · Miscellaneous Directories fr Capital, $200,000. Resources, $8,000,000. % POWERS BUILDING, % ROCHESTER, NEW YORK. * TRANSACTS A GENERAL BANKING AND TRUST BUSINESS % * Pays the Highest Rate of Interest •$» Consistent With Safe Banking. -

The Tragedy of Transportation: Underfunding Our Future Richard Ravitch Former Lieutenant Governor, New York

The Alan M. Voorhees Transportation Center and the Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy present THE ALAN M. VOORHEES DISTINGUISHED LECTURE Monday, November 11, 2013, 5:00 p.m. Special Events Forum, Civic Square Building The Tragedy of Transportation: Underfunding our Future Richard Ravitch Former Lieutenant Governor, New York Richard Ravitch is a lawyer, businessman, and public official who has been engaged in private and public business for more than 50 years. Mr. Ravitch is drawn to public service as a lifelong New Yorker. Educated at Columbia College and Yale Law School, he has become known as “Mr Fix-It” because of his “renaissance man” abilities to problem solve difficult problems. In 2012, he co-chaired the New York State Budget Crisis Task Force. He served as Lieutenant Governor of the State of New York from 2009 to 2010. Prior to his appointment as Lieutenant Governor, Mr. Ravitch served as chairman of the New York State Urban Development Corporation, the Bowery Savings Bank, HRH Construction Corporation, and AFL-CIO Housing Investment Trust. He also was called upon by Major League Baseball to negotiate a labor agreement on behalf of the owners. Mr. Ravitch was also selected by Governor Hugh Carey to lead the Metropolitan Transportation Authority in 1979 during the agency’s most troubled time. He is widely credited as having been the catalyst for the restoration of the MTA in subsequent years. A reception will follow the lecture. Please RSVP by Friday, November 1 to Stephanie Kose by phone at 848-932-2832 or by e-mail to [email protected]. -

AP United States History Summer Assignment 2017 Mr. John Raines Summer Contact: [email protected]

AP United States History Summer Assignment 2017 Mr. John Raines Summer contact: [email protected] Summer Assignment Directions and Parent Letter Dear Students and Parents: I am excited that you have decided to accept the challenge of taking an Advanced Placement class, which is a university-level course taught in high school. I promise that you will strengthen your academic, intellectual, observation, and discussion skills. Additionally, I promise that each of you will become a stronger writer from this course. I am excited to teach this class again next year and I am dedicated to providing a challenging and rewarding academic experience. The first question you have to answer is WHY ARE YOU TAKING THIS COURSE? Possible answers include: It will look good on my transcript. My parents are making me do it. My friends are taking it. I took AP World History. I love The History Channel. I want the challenge of a demanding, nearly impossible course. I don’t need sleep and love writing essays and answering difficult multiple-choice tests. I want to get a 5 on the AP Test and brag about it to my friends and relatives. All of these are good answers, but none of these in themselves are good enough. That is, an AP history student must be dedicated whole-heartedly to this course. It is expected that you will spend several hours each week preparing for this course. As a part of this course you will be consistently be reading several different sources. Failure to stay up on the reading is unacceptable for a college-level course and will result in poor performance in this course. -

FY13 Annual Report View Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2012–13 3 Introduction 5 Metropolitan Opera Board of Directors 7 2012–13 Season Repertory & Events 14 2012–13 Artist Roster 15 The Financial Results 46 Patrons Introduction The Metropolitan Opera’s 2012–13 season featured an extraordinary number of artistic highlights, earning high praise for new productions, while the company nevertheless faced new financial challenges. The Met presented seven new stagings during the 2012–13 season, including the Met premieres of Thomas Adès’s The Tempest and Donizetti’s Maria Stuarda, the second of the composer’s trilogy of Tudor operas (with the third installment planned for a future season). All seven new productions, plus five revivals, were presented in movie theaters around the world as part of the Met’s groundbreaking Live in HD series, which continued to be an important revenue source for the Met, earning $28 million. Combined earned revenue for the Met (Live in HD and box office) totaled $117.3 million. This figure was lower than anticipated as the company continued to face a flat box office, complicated by the effects of Hurricane Sandy, the aftermath of which had a negative impact of approximately $2 million. As always, the season featured the talents of the world’s leading singers, conductors, directors, designers, choreographers, and video artists. Two directors made stunning company debuts: François Girard, with his mesmerizing production of Parsifal on the occasion of Wagner’s bicentennial, and Michael Mayer, whose bold reimagining of Verdi’s Rigoletto in 1960 Las Vegas was the talk of the opera world and beyond. Robert Lepage returned to direct the highly anticipated company premiere of Thomas Adès’s The Tempest, with the composer on the podium. -

CPY Document

................... ........ .......... ... SHORT FORM ORDER SUPREME COURT - STATE OF NEW YORK NASSAU COUNTY - PART 15 Present: HON. WILLIAM R. LaMARCA Justice DEAN G. SKELOS and PEDRO ESPADA, JR., Motion Sequence #1, #2, #3 15, 2009 as duly elected members of the New York Submitted: July State Senate, Plaintiffs, -against- INDEX NO: 13426/09 DAVID PATERSON, as Governor of the State of New York and RICHARD RAVITCH, as putative nominee for Lieutenant Governor of the State of New York and LORRAINE CORTES-VASQUEZ, as Secretary of State of the State of New York, Defendants. The following papers were read on these motions: Notice of Motion/Order to Show Cause for Prelim inary Injunction.... Notice of Cross-Motion to Cis miss.......................................................................... Affrmation in Opposition to Motion in Chief and in Support of Cross-Motion............................. Defendants' Memorandum of Law in Opposition to Motion in Chief and in Support of Cross-Motion............................... Notice of Motion/Order to Show Cause for Change of Venue ........................................................ Affrmation in Support of Motion to Change V en ue......................... ........ .......... ....... Defendants' Memorandum of Law in Support of Motion to Change Venue......................... ............................................................................. ... Affirmations in Opposition to Cross-Motion and Motion to Change Venue.................................... Affidavit of Daniel Shapi ro.............. -

MOYNIHAN STATION PROJECT SEMINAR and TOUR Tuesday, April 29, 2014 | 8:00 AM – 10:00 AM

THE GREATER NEW YORK CONSTRUCTION USER COUNCIL PRESENTS MOYNIHAN STATION PROJECT SEMINAR AND TOUR Tuesday, April 29, 2014 | 8:00 AM – 10:00 AM JAMES A. FARLEY BUILDING Enter at North West Corner of 31st Street and 8th Avenue New York, NY The Moynihan Station Project will redevelop the landmarked James A. Farley Post Office Building into the new Manhattan home for Amtrak, transforming a treasured building into an iconic railroad passenger station and mixed-use development befitting New York City. In May 2012, MSDC awarded a $147,750,000 construction contract to Skanska USA Civil Northeast for the West End Concourse Expansion. Construction on the West End Concourse Expansion began in September 2012 with the first weekend closures of individual Penn Station tracks and platforms in order to facilitate surveying, the relocation of utilities, and preliminary foundation work for the new concourse. This type of work will continue until mid-2014 when the technically challenging steel erection phase will begin. In September 2012, the Federal Railroad Administration awarded Moynihan Station a $30 million High Speed Rail Grant through the New York State Department of Transportation for the Connecting Corridor construction and the first portion of the new Emergency Ventilation System. This event will feature a panel discussion with key project stakeholders from Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, the Port Authority of New York & New Jersey and the Moynihan Station Development Corporation. A short tour of the project site will follow the panel discussion. SPEAKERS MICHAEL J. EVANS | PRESIDENT | MOYNIHAN STATION DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION Michael Evans serves under New York State Governor Andrew Cuomo as President of the Moynihan Station Development Corporation, the New York State public authority charged with building a new intercity passenger rail station for New York City within the landmarked James A Farley Post Office Building. -

Government, Law and Policy Journal

NYSBA SUMMER 2011 | Vol. 13 | No. 1 Government, Law and Policy Journal A Publication of the New York State Bar Association Committee on Attorneys in Public Service, produced in cooperation with the Government Law Center at Albany Law School NNewew YYorkork SState’state’s BBudget:udget: CConflictsonflicts aandnd CChallengeshallenges In Memoriam Governor Hugh L. Carey 1919-2011 The Committee on Attorneys in Public Service dedicates this issue to the enduring memory of Governor Hugh L. Carey and his enumerable contributions to public service This photograph, which is entitled Governor Carey Briefs the Press on the Budget, was made available from the New York State Archives. SUMMER 2011 | VOL. 13 | NO. 1 Government, Law and Policy Journal Contents Board of Editors 2 Message from the Chair J. Stephen Casscles Peter S. Loomis Lisa F. Grumet 3 Editor’s Foreword James F. Horan Rose Mary K. Bailly Barbara F. Smith 4 Guest Editor’s Foreword Patricia K. Wood Abraham M. Lackman Staff Liaison 5 Legal History of the New York State Budget Albany Law School David S. Liebschutz and Mitchell J. Pawluk Editorial Board 11 Pataki v. Assembly: The Unanswered Question Rose Mary K. Bailly Hon. James M. McGuire Editor-in-Chief 17 New York State School Finance Patricia E. Salkin Shawn MacKinnon Director, Government Law Center 24 CFE v. State of New York: Past, Present and Future Michael A. Rebell Vincent M. Bonventre Founding Editor-in-Chief 31 Changing the Terms of New York State’s Budget Conversation Richard Ravitch Student Editors 35 New York’s Economy: From Stagnation to Decline Robert Barrows Abraham M. -

An Autobiography by Theodore Roosevelt

An Autobiography By Theodore Roosevelt An Autobiography by Theodore Roosevelt CHAPTER I BOYHOOD AND YOUTH My grandfather on my father's side was of almost purely Dutch blood. When he was young he still spoke some Dutch, and Dutch was last used in the services of the Dutch Reformed Church in New York while he was a small boy. About 1644 his ancestor Klaes Martensen van Roosevelt came to New Amsterdam as a "settler"—the euphemistic name for an immigrant who came over in the steerage of a sailing ship in the seventeenth century instead of the steerage of a steamer in the nineteenth century. From that time for the next seven generations from father to son every one of us was born on Manhattan Island. My father's paternal ancestors were of Holland stock; except that there was one named Waldron, a wheelwright, who was one of the Pilgrims who remained in Holland when the others came over to found Massachusetts, and who then accompanied the Dutch adventurers to New Amsterdam. My father's mother was a Pennsylvanian. Her forebears had come to Pennsylvania with William Penn, some in the same ship with him; they were of the usual type of the immigration of that particular place and time. They included Welsh and English Quakers, an Irishman,—with a Celtic name, and apparently not a Quaker,—and peace-loving Germans, who were among the founders of Germantown, having been driven from their Rhineland homes when the armies of Louis the Fourteenth ravaged the Palatinate; and, in addition, representatives of a by-no- means altogether peaceful people, the Scotch Irish, who came to Pennsylvania a little later, early in the eighteenth century. -

Year in Review 2006

CELEBRATING 24 YEARS OF LAND CONSERVATION VOL. 18, No 1 YEAR IN REVIEW: 2006 President’s Column A Celebration of Our Donors s the Peconic Land Trust enters its 24th year, devel- out shellfish and baymen/women to harvest them? What opment pressures continue to impact the owners of is a community without a diversity of people, young and Aworking farms and natural lands in staggering old, white and of color, of wealth and modest means? As ways, whether due to the specter of federal estate taxes or property values and development increase, we risk losing the sheer difficulty of owning and maintaining valuable not only our agricultural heritage and natural diversity, land in our changing communities. What is amazing to me but our cultural and economic diversity as well. So, in is that, despite these pressures and the anxiety that accom- addition to conserving land, we are seeking ways to con- panies them, so many landowners have an incredible will serve our communities by adapting the tools we use to and determination to hold onto their land… and that is protect land so that diverse communities of people can live where the Trust comes in. We listen to the needs and goals and survive on Long Island. In so doing, we must make of landowners, we study their land and the resources there- conservation and our mission relevant to all. in, and we come up with practical and pragmatic ways to conserve land, farms, and ways of life. We cannot conserve the land we know and love (as well as the communities therein) alone and that is where you As we continue with the planning, land protection, and come in. -

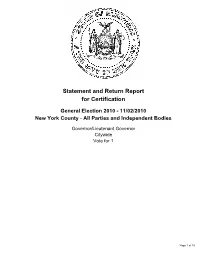

Statement and Return Report for Certification General Election 2010

Statement and Return Report for Certification General Election 2010 - 11/02/2010 New York County - All Parties and Independent Bodies Governor/Lieutenant Governor Citywide Vote for 1 Page 1 of 19 BOARD OF ELECTIONS Statement and Return Report for Certification IN THE CITY OF NEW YORK General Election 2010 - 11/02/2010 PRINTED AS OF: New York County 11/30/2010 9:09:59AM All Parties and Independent Bodies Governor/Lieutenant Governor (Citywide), vote for 1 Assembly District 64 PUBLIC COUNTER 21,353 EMERGENCY 0 ABSENTEE/MILITARY 416 AFFIDAVIT 743 Total Ballots 22,693 ANDREW M CUOMO / ROBERT J DUFFY (DEMOCRATIC) 16,266 CARL P PALADINO / GREGORY J EDWARDS (REPUBLICAN) 2,519 ANDREW M CUOMO / ROBERT J DUFFY (INDEPENDENCE) 553 CARL P PALADINO / GREGORY J EDWARDS (CONSERVATIVE) 234 ANDREW M CUOMO / ROBERT J DUFFY (WORKING FAMILIES) 1,355 HOWIE HAWKINS / GLORIA MATTERA (GREEN) 192 JIMMY MCMILLAN (RENT IS 2 DAMN HIGH) 249 WARREN REDLICH / ALDEN LINK (LIBERTARIAN) 195 KRISTIN M DAVIS / TANYA GENDELMAN (ANTI-PROHIBITION) 163 CHARLES BARRON / EVA M DOYLE (FREEDOM) 147 CARL P PALADINO / GREGORY J EDWARDS (TAXPAYERS) 18 A ANDRE (WRITE-IN) 1 DAN FEIN HARRY DAGOSTINO (WRITE-IN) 1 DAVID PATERSON (WRITE-IN) 1 DAVID THE VOICE STEIN (WRITE-IN) 1 DONALD DUCK (WRITE-IN) 1 EDUMAND C BURNS (WRITE-IN) 1 JOHN A GOLEC (WRITE-IN) 2 MARGARET TRINGLE (WRITE-IN) 1 MARIAN M CHEN (WRITE-IN) 1 MICHAEL BLOOMBERG (WRITE-IN) 2 NEED MORE CHOICES (WRITE-IN) 1 NO NAME (WRITE-IN) 3 NONE OF THE FOREGOING (WRITE-IN) 1 R.A. DICKEY (WRITE-IN) 1 SAM FEIN (WRITE-IN) 1 VIC RALTTLEHAND -

The Man Who Saved New York

Introduction ate one afternoon in May, 1980, Governor Hugh L. Carey and an assis- Ltant counsel were returning to his offi ce after a public event marking the fi fth anniversary of the court consent decree to close the Willowbrook Development Center in Staten Island, New York, a nightmarish institution for the developmentally disabled. Carey’s aide, Clarence Sundram, knew that throughout his political career in Washington and Albany, the governor had dedicated himself to the needs of the disabled. As their car carried them back toward Manhattan, Carey turned to face Sundram, saying that while people would probably credit him fi rst and foremost with rescuing the city and the state from the brink of bankruptcy during the great New York City fi scal crisis of 1975, he personally was proudest of signing the legal agree- ment that began the process of fi nally placing Willowbrook’s poorly served residents in small neighborhood group homes and day care sites around the state. It was a long-overdue step that set a humane standard for the treat- ment of the retarded. For any politician, merely rescuing New York from the cliff ’s edge of economic collapse would have been accomplishment enough. But Carey, fre- quently mistaken during his extensive career for a traditional Irish-American machine politician, harbored a principled and progressive sense of public responsibility and purpose. Unlike many contemporary politicians who infl ate a kernel of achievement into an exaggerated resume while relying on armies of consultants, speechwriters, and pollsters, Carey led a substantial life. He grew up during the Great Depression, fought in World War II and helped liberate a Nazi death camp, and ran for Congress.