The Multiple Paths of Italian Designers in Argentina, 1948-58

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Influence of International Town Planning Ideas Upon Marcello Piacentini’S Work

Bauhaus-Institut für Geschichte und Theorie der Architektur und Planung Symposium ‟Urban Design and Dictatorship in the 20th century: Italy, Portugal, the Soviet Union, Spain and Germany. History and Historiography” Weimar, November 21-22, 2013 ___________________________________________________________________________ About the Internationality of Urbanism: The Influence of International Town Planning Ideas upon Marcello Piacentini’s Work Christine Beese Kunsthistorisches Institut – Freie Universität Berlin – Germany [email protected] Last version: May 13, 2015 Keywords: town planning, civic design, civic center, city extension, regional planning, Italy, Rome, Fascism, Marcello Piacentini, Gustavo Giovannoni, school of architecture, Joseph Stübben Abstract Architecture and urbanism generated under dictatorship are often understood as a materialization of political thoughts. We are therefore tempted to believe the nationalist rhetoric that accompanied many urban projects of the early 20th century. Taking the example of Marcello Piacentini, the most successful architect in Italy during the dictatorship of Mussolini, the article traces how international trends in civic design and urban planning affected the architect’s work. The article aims to show that architectural and urban form cannot be taken as genuinely national – whether or not it may be called “Italian” or “fascist”. Concepts and forms underwent a versatile transformation in history, were adapted to specific needs and changed their meaning according to the new context. The challenge is to understand why certain forms are chosen in a specific case and how they were used to create displays that offer new modes of interpretation. The birth of town planning as an architectural discipline When Marcello Piacentini (1881-1960) began his career at the turn of the 20th century, urban design as a profession for architects was a very young discipline. -

MARCO ZANUSO and RICHARD SAPPER: SELECTIONS FRON the DESIGN COLLECTION August 19 - November 9, 1993

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release August 1993 MARCO ZANUSO AND RICHARD SAPPER: SELECTIONS FRON THE DESIGN COLLECTION August 19 - November 9, 1993 An exhibition of twenty objects designed by Marco Zanuso and Richard Sapper opens at The Museum of Modern Art on August 19, 1993. Organized by Anne Dixon, study center supervisor, Department of Architecture and Design, NARCO ZANUSO AND RICHARD SAPPER: SELECTIONS FRON THE DESIGN COLLECTION includes televisions, appliances, chairs, and a variety of other objects designed by Zanuso and Sapper, working both individually and in collaboration, from 1959 to 1978. The exhibition highlights the ways in which Zanuso's and Sapper's designs manifest an understanding of the relationship of user to object, embodying what Zanuso has called the "metaphoric quality which objects have for those who use them." It is the exploitation of this metaphoric quality that endows their products with a level of emotional and intellectual meaning usually outside the realm of product design. The range of meanings evoked by the designs is broad. The "Grillo" telephone, for instance, is a pleasing, shell-like object which affirms the intimacy of conversation. The "Doney 14" television, with minimal casing around the picture tube, is an object in which simple design establishes a straightforward dialogue with the viewer, while the "Black 201" television is a solid black cube that reveals the screen behind its translucent face only when turned on. Designed during the Vietnam war -- often called the first -more- 11 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019-5498 Tel: 212-708-9400 Cable: MODERNART Telex: 62370 MODART 2 televised war -- the "Black 201" raises questions about information and power. -

Frank Lloyd Wright in Venice and the Masieri Memorial

MODERNISM CONTESTED: FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT IN VENICE AND THE MASIERI MEMORIAL DEBATE by TROY MICHAEL AINSWORTH, B.A., M.A. A DISSERTATION IN LAND-USE PLANNING, MANAGEMENT, AND DESIGN Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Michael Anthony Jones Co-Chairperson of the Committee Bryce Conrad Co-Chairperson of the Committee Hendrika Buelinckx Paul Carlson Accepted John Borrelli Dean of the Graduate School May, 2005 © 2005, Troy Michael Ainsworth ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The task of writing a dissertation is realized through the work of an individual supported by many others. My journey reflects this notion. My thanks and appreciation are extended to those who participated in the realization of this project. I am grateful to Dr. Michael Anthony Jones, now retired from the College of Architecture, who directed and guided my research, offered support and suggestions, and urged me forward from the beginning. Despite his retirement, Dr. Jones’ unfaltering guidance throughout the project serves as a testament to his dedication to the advancement of knowledge. The efforts and guidance of Dr. Hendrika Buelinckx, College of Architecture, Dr. Paul Carlson, Department of History, and Dr. Bryce Conrad, Department of English, ensured the successful completion of this project, and I thank them profusely for their untiring assistance, constructive criticism, and support. I am especially grateful to James Roth of the John F. Kennedy Library in Boston, Massachusetts, for his assistance, and I thank the John F. Kennedy Library Foundation for awarding me a research grant. Likewise, I extend my thanks to the Ernest Hemingway Foundation and Society for awarding me its Paul Smith-Michael Reynolds Founders Fellowship to enable my research. -

Cersaie Bologna | International Exhibition of Ceramic Tile

INTINTERNATIONAL EXHIBITION OF CERAMIC TILE AND BATHROOM FURNISHINGS 28 SEPTEMBER - 2 OCTOBER 201 Cersaie Bologna | International Exhibition of Ceramic Tile ... ERNATIONAL EXHIBITION OF CERA AND BATHROOM FURNISHINGS Home > Events > Protagonists Protagonists Claudio Musso Digicult Network Oscar G. Colli Biographical notes Columnist for the magazine “il Bagno Oggi e Domani” of which he was co-founder and editorial director. He is been part for about 16 years of the ADI’s Permanent Observatory of Design. From 2008 to 2010 he directed the selection and publication on the ADI-Design-Index of the best products and services among which the winners of the “Compasso d’Oro” are selected. He held many conferences and talks with students in various universities and he is often moderator for conventions and seminars about interior design and industrial design. Marco Vismara Architect Biographical notes Studio D73 by Marco Vismara and Andrea Viganò is specialized in architectural and design projects in a wide international dimension. Studio D73 deals with interior design, different commercial and private projects, from analysis to production, and carries out the project phases thanks to a very efficient team of professionals based in the headquarter in Italy and the two other offices in Moscow, Tunis and Tbilisi. Within the past few years, Studio D73 has grown and reached many countries abroad, mainly in Russia, East Europe and North Africa, with the aim of keeping growing in new countries in the near future. State-of- the-art design project solutions by Studio D73 include Spa, hotel, showroom, and residential buildings. Giampietro Sacchi Interior designer Biographical notes Interior designer and director of the masters “High education design” at POLI.design – Polytechnic University of Milan. -

Italia'61 a Century of Italian Architecture, 1861-19611

PERIODICA POLYTECHNICA SER. ARCHITECTURE VOL. 30', NOS. 1-4, PP. 77-96 (1992) ITALIA'61 A CENTURY OF ITALIAN ARCHITECTURE, 1861-19611 Ferenc MERENYI Institute of History and Theorie of Architecture, Technical University of Budapest H-1.521 Budapest, Hungary This idea of mine and then the intention to get to know more throroughly, with its interconnecctions and contradictions, the architecture of a country which has an extremely complex historical past, and yet is barely one hun dred years old, was finally conceived, although not without antecedents, in the April of 1961. That spring Turin, the 'capital' of FIAT, was preparing for centenary festivities. One hundred years before, on the 17th March of 1861, after the adhering of Tuscany, and then Sicily, Naples, the Marches (Marche) and Umbric., the Parliament of Turin proclamed Victor Emman ual II King of Italy and thus, with the exception of Venice and Rome for the time being, unified Italy was born. To celebrate this historical event the city of Turin and the executives of the FIAT works organized a large national exhibition 'Italia'61', displaying the economic, social, political and cultural development and results of the one hundred years. \Vell, that specific April morning I shared with Italian and foreign colleagues the unforgettable ex perience of having the chance to stand in the middle of the Palazzo del Lavoro, the Labour Hall, (Fig. 1) just before completion, and to listen to the wise and patient answers of Professor PIER LmGI NERVI to questions not always benevolent. A wanton 'forest of columns?' He answered with a sligthly wry smile of the scholar forced to give explanations: ' No, signori .. -

The Meaning of Italian Culture in the Latin American Architecture Historiography

CADERNOS 19 ROBERTO SEGRE The Meaning of Italian Culture in the Latin American Architecture Historiography. An Autobiographical Essay. ROBERTO SEGRE The Meaning of Italian Culture in the Latin American 291 Architecture Historiography. An Autobiographical Essay. Roberto Segre Picture: Meindert Versteeg (2010) The first years he decision of writing an autobiographical narrative is a difficult task, as- Tsuming as guideline the meaning of Italy and its culture, for seven decades dedicated to the history of Architecture. It gives the impression that telling your own life story is somehow associated with an egocentric, self-recognition content; with the illusion of an idea that personal experiences would be useful to eventual readers. However, at the same time, there is in the world a persis- tent and intense desire of knowing the individualities that through their work contributed to the development of culture and ideas that had some influence on the social development; those who fought for transforming reality by gen- erating new empirical contents, interpretations, discoveries and experiences that could be embraced by future generations. Therefore, reaching an advanced age, we feel the need of stopping, of looking back to the past and following the singer Paolo Conte’s suggestion: “dai, dai, via, via, srola la pellicola”, and thus, reviewing the most significant moments of life: the discoveries during travels, the contact with the masters, the aesthetic and architectonic experiences. Un- doubtedly some autobiographies are still paradigmatic, such as the ones by F.L. Wright and Oscar Niemeyer; or the more intimate and personal ones by Peter Blake, V.G. Sebald or Eric Hobsbawm. -

Aldo Rossi – Architect and Theorist. the Dilemmas of Architecture After Modernism 1

ALDO ROSSI – ARCHITECT AND THEORIST. THE DILEMMAS OF ARCHITECTURE AFTER MODERNISM 1 JUSTYNA WOJTAS SWOSZOWSKA From a 21st century perspective the characteristic foremost his theory of Neo-Rational architecture, work of Aldo Rossi (1931-1997) 2, the Italian architect, explained in masterly fashion in numerous essays theorist, artist, and designer, may look anachronistic. and treatises. To present an honest evaluation of Aldo Today, he is considered a representative of Rossi’s work against the background of changes postmodernism, though he referred to himself as in architecture in the second half of the twentieth a premodernist 3. In his designs he applied historical century, we must look at his work in its entirety. canons, taking them without “a pinch of salt”, as did many postmodernists who followed Robert Venturi. The Mediterranean origin of historical tendencies His inspirations were derived from the world around in architecture him, since he considered observation to be the best school of architecture. He used the basic Platonic Aldo Rossi’s career in architecture began in the solids, from which, as if from building blocks, he 1960s, when the rapid economic growth of developed created monumental architecture, concise in form countries made clear the ineffectuality of the doctrines or almost fairy-tale like (ill. 1, 2). Karen Stein 4, of mature modernism. In philosophy, politics, an American architecture critic, sees a similarity culture, art, a period of postmodernism began, a time between the creations of Aldo Rossi and the looks of of violating modernist doctrines. In architecture, the Pinocchio, Carlo Collodi’s [ ctional character: “his paradigm of the modernist movement was questioned cylindrical body, gangly columnar legs and arms, and a “revolution the against revolution” 7 began. -

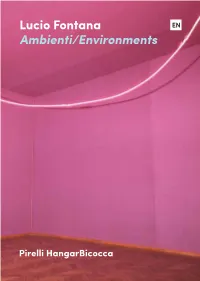

Lucio Fontana Ambienti/Environments

Lucio Fontana 1 Lucio Fontana EN Ambienti/Environments Pirelli HangarBicocca 2 Pirelli HangarBicocca Cover Lucio Fontana, Ambiente spaziale con neon, 1967. Lucio Fontana Photo: Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam. Ambienti/Environments Public Program | Lucio Fontana 21 September 2017 – 25 February 2018 Find out more about the events accompanying the exhibition in our website curated by Marina Pugliese, Barbara Ferriani and Vicente Todolí Cultural Mediation To learn more about the exhibition ask to the cultural mediators in the space In collaboration with Fondazione Lucio Fontana #ArtToThePeople Pirelli HangarBicocca Via Chiese, 2 20126 Milan IT Opening Hours Thursday to Sunday 10 am – 10 pm Monday to Wednesday closed Contacts T +39 02 66111573 [email protected] hangarbicocca.org FREE ENTRY Pirelli HangarBicocca 4 Pirelli HangarBicocca 5 The Artist Lucio Fontana (Rosario, Argentina, 1899 – Varese, Italy, 1968) is internationally renowned as one of the most innovative artists of the 20th century. His work was a major influence for subse- quent generations of artists, and its originality continues to resonate today. Fascinated by the cosmos and well-aware of the new horizons opening up thanks to scientific discoveries of his day, Fontana investigated the concepts of material, space, light and void, using in his works widely different materials to expand the boundaries of art. Alongside ceramic, plaster, cement and paint, he experimented with neon lighting, Wood lights and fluorescent painting, as well as with new media like television. Fontana theorized his artistic vision in several manifestos, out- lining his own research through definition of the Spatial Movement—also known as Spazialismo, or Spatialism—which the artist founded in Italy in 1947. -

In Fascist Italy

fascism 7 (2018) 45-79 brill.com/fasc Futures Made Present: Architecture, Monument, and the Battle for the ‘Third Way’ in Fascist Italy Aristotle Kallis Keele University [email protected] Abstract During the late 1920s and 1930s, a group of Italian modernist architects, known as ‘ra- tionalists’, launched an ambitious bid for convincing Mussolini that their brand of ar- chitectural modernism was best suited to become the official art of the Fascist state (arte di stato). They produced buildings of exceptional quality and now iconic status in the annals of international architecture, as well as an even more impressive register of ideas, designs, plans, and proposals that have been recognized as visionary works. Yet, by the end of the 1930s, it was the official monumental stile littorio – classical and monumental yet abstracted and stripped-down, infused with modern and traditional ideas, pluralist and ‘willing to seek a third way between opposite sides in disputes’, the style curated so masterfully by Marcello Piacentini – that set the tone of the Fascist state’s official architectural representation. These two contrasted architectural pro- grammes, however, shared much more than what was claimed at the time and has been assumed since. They represented programmatically, ideologically, and aestheti- cally different expressions of the same profound desire to materialize in space and eternity the Fascist ‘Third Way’ future avant la lettre. In both cases, architecture (and urban planning as the scalable articulation of architecture on an urban, regional, and national territorial level) became the ‘total’ media used to signify and not just express, to shape and not just reproduce or simulate, to actively give before passively receiv- ing meaning. -

From Architecture to Design and Back

Res Mobilis Revista internacional de investigación en mobiliario y objetos decorativos Vol. 9, nº. 10, 2020 FROM ARCHITECTURE TO DESIGN AND BACK: THE ARCHITECTURAL ROOTS OF THE ITALIAN DESIGN SYSTEM, 1920-1980 DE LA ARQUITECTURA AL DISEÑO IDA Y VUELTA: LAS RAÍCES ARQUITECTÓNICAS DEL SISTEMA DE DISEÑO ITALIANO, 1920-1980 Elena Dellapiana* Politecnico di Torino Fiorella Bulegato Università IUAV di Venezia Abstract The histories of Italian design and architecture may be more readily understood if one considers that many of the protagonists are architect-designers. Identifying the root of this convergence in an academic and professional educational system based on the idea of the "complete architect", trained to work at any scale of design, this paper frames the work of the architect-designers within the cultural, economic and manufacturing context of the period between the 1920s and 1980s, when for historical reasons their role became particularly significant. Furthermore, many design historians in Italy are the product of the same education as the architects, and having followed the same course of studies as the architectural historians, they acquired the same techniques of investigation and interpretation, which they later refined in their own fields. The theme is thus explored from the perspectives of the two authors, both architects but with specific training one as an architectural historian, and the other as a design historian. The relationship between the two research directions – the theoretical debate and its narrations, the relationship between designers and manufacturers – makes it possible to clarify some of the aspects that distinguish the history of Italian design culture compared to that of other Western nations. -

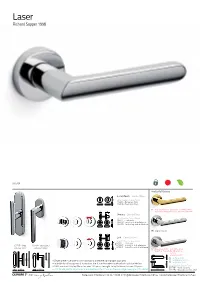

Richard Sapper 1998

Laser Richard Sapper 1998 M176R material/brass Escutcheon - Studio Olivari 51 Specification Code + Finish 1191E - European Style 1191O - Australian Style 10 60 IB superinox brass - guaranteed not to pitt or 13 34 tarnish for 30 years in sea air environments 60 Verona - Studio Olivari 30 Specification Code + Finish 51 H107S - snib only 47 H107V6 - privacy snib & eRelease H107F6 - indicating snib & eRelease 10 63 63 CR bright chrome 138 130 13 32 9 28 Link - Piero Lissoni Specification Code + Finish H200S - snib only 60 51 C176R - fixed K176R - operational 47 H200V6 - privacy snib & eRelease window slider window handle H200F6 - indicating snib & eRelease 5 10 IS superinox satin - guaranteed not to pitt or tarnish for 30 years in 60 sea air environments30 71 51 AS antique silver 126 166 PC powdercoat colours 150 • Single piece rose with torsion springs & a lifetime spring back warranty BZ antique bronze • Suitable for all European & Australian fire & non fire rated mortice locks & tube latches 63 63 • 100% made in Italy by Olivari for over 100 years, brought to by Bellevue for over 30 years Specification Code + Finish M176R1 - lever set only 37 62 32 66 • This handle and its accessories are available on the “L” low profile rose range. See page 19 for details 138 M176R2 - passage130 set incl. latch Bellevue Architectural | 03 9571 5666 | [email protected] | www.bellevuearchitectural.com.au 100 Years of Excellence pantone 5483 62 9 20 27 71 126 166 150 37 62 32 66 Bellevue Architectural | 03 9571 5666 | [email protected] | www.bellevuearchitectural.com.au 100 Years of Excellence pantone 5483 62 9 20 27 Richard Sapper Munich, 1932 Born in Munich, Sapper studied economy and engineering. -

DESIGN-English 2.Indd 203 5/8/14 10:24 PM Preceding Page Below Opposite 240

germany and switzerland Jeremy Aynsley DESIGN-english 2.indd 203 5/8/14 10:24 PM preceding pAge below opposite 240. Konstantin Grcic (b. 1965) 241. Wilhelm Kienzle 242. Wilhelm Wagenfeld Chair_ONE, 2003 (1886–1958) (1900–1990) Made by Magis (Italy) Watering can, 1935 Kubus stackable glass See plate 289. Reissued by Mewa Blattmann containers, 1938 (Switzerland), 1991 Made by Vereinigte Lausitzer Museum für Gestaltung, Glaswerke (Germany) Zurich Molded glass Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum, New York From a contemporary perspective, it is clear that post- war design in Germany and Switzerland fulfilled the promise of early twentieth-century modernism while also questioning some of its basic principles and offer- ing new ways of thinking. Both these countries had established reputations for design that put them in a good position to revive traditions after the trauma of World War II. The situation varied considerably between the two, however. In Germany, modern design- ers negotiated the political disruption, censorship, and fatal consequences of the Third Reich and ensuing war only to find themselves in a divided country in 1949, with the founding of the Federal Republic of Germany design, instead embracing the terms “paradox” and (FRG) allied to Western forces and the Soviet-oriented “contrast.” He observed that Swiss design is rarely German Democratic Republic (GDR) in the east. By marked by “effusive indulgence” and tends to employ contrast, Switzerland, as a neutral country during the an “intelligent economy of means,” not “expensive so- war, offered greater possibilities of cultural continuity, lutions.” Swiss designers, he contended, “avoid theatri- becoming a vital center for design during the troubled cality” while still taking creative risks, which he saw as early postwar years.