Brown Bears of Unit 4 Past, Present and Future: a Status Report and Issues Paper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wilderness in Southeastern Alaska: a History

Wilderness in Southeastern Alaska: A History John Sisk Today, Southeastern Alaska (Southeast) is well known remoteness make it wild in the most definitive sense. as a place of great scenic beauty, abundant wildlife and The Tongass encompasses 109 inventoried roadless fisheries, and coastal wilderness. Vast expanses of areas covering 9.6 million acres (3.9 million hectares), wild, generally undeveloped rainforest and productive and Congress has designated 5.8 million acres (2.3 coastal ecosystems are the foundation of the region’s million hectares) of wilderness in the nation’s largest abundance (Fig 1). To many Southeast Alaskans, (16.8 million acre [6.8 million hectare]) national forest wilderness means undisturbed fish and wildlife habitat, (U.S. Forest Service [USFS] 2003). which in turn translates into food, employment, and The Wilderness Act of 1964 provides a legal business. These wilderness values are realized in definition for wilderness. As an indicator of wild subsistence, sport and commercial fisheries, and many character, the act has ensured the preservation of facets of tourism and outdoor recreation. To Americans federal lands displaying wilderness qualities important more broadly, wilderness takes on a less utilitarian to recreation, science, ecosystem integrity, spiritual value and is often described in terms of its aesthetic or values, opportunities for solitude, and wildlife needs. spiritual significance. Section 2(c) of the Wilderness Act captures the essence of wilderness by identifying specific qualities that make it unique. The provisions suggest wilderness is an area or region characterized by the following conditions (USFS 2002): Section 2(c)(1) …generally appears to have been affected primarily by the forces of nature, with the imprint of man’s work substantially unnoticeable; Section 2(c)(2) …has outstanding opportunities for solitude or a primitive and unconfined type of recreation; Section 2(c)(3) …has at least five thousand acres of land or is of sufficient FIG 1. -

Brown Bear (Ursus Arctos) John Schoen and Scott Gende Images by John Schoen

Brown Bear (Ursus arctos) John Schoen and Scott Gende images by John Schoen Two hundred years ago, brown (also known as grizzly) bears were abundant and widely distributed across western North America from the Mississippi River to the Pacific and from northern Mexico to the Arctic (Trevino and Jonkel 1986). Following settlement of the west, brown bear populations south of Canada declined significantly and now occupy only a fraction of their original range, where the brown bear has been listed as threatened since 1975 (Servheen 1989, 1990). Today, Alaska remains the last stronghold in North America for this adaptable, large omnivore (Miller and Schoen 1999) (Fig 1). Brown bears are indigenous to Southeastern Alaska (Southeast), and on the northern islands they occur in some of the highest-density FIG 1. Brown bears occur throughout much of southern populations on earth (Schoen and Beier 1990, Miller et coastal Alaska where they are closely associated with salmon spawning streams. Although brown bears and grizzly bears al. 1997). are the same species, northern and interior populations are The brown bear in Southeast is highly valued by commonly called grizzlies while southern coastal populations big game hunters, bear viewers, and general wildlife are referred to as brown bears. Because of the availability of abundant, high-quality food (e.g. salmon), brown bears enthusiasts. Hiking up a fish stream on the northern are generally much larger, occur at high densities, and have islands of Admiralty, Baranof, or Chichagof during late smaller home ranges than grizzly bears. summer reveals a network of deeply rutted bear trails winding through tunnels of devil’s club (Oplopanx (Klein 1965, MacDonald and Cook 1999) (Fig 2). -

Admiralty Island National Monument

ADMIRALTY ISLAND NATIONAL MONUMENT DESCRIPTION At a glance: Admiralty Island National Monument (NM) is located on Admiralty Island NM quick facts Admiralty Island, 15 miles southwest of Juneau in south- east Alaska, and is accessible only by water or air. The Date established: Dec. 1, 1978; Dec. 2, 1980 island is characterized by rugged coastline, remote old growth rainforest, towering mountains, and alpine tundra Established by: Presidential proclamation, President with permanent icefields. It hosts the largest concentration Jimmy Carter (1978); Congressional designation, Public of brown bears and nesting bald eagles in the world, as Law 96-487 (1980) well as harbor seals, porpoises and sea lions, humpback Forest Service region: 10, Alaska Region whales, and all five species of Pacific salmon in its waters. More than 90 percent of the monument is designated as State: Alaska the Kootznoowoo Wilderness, nearly 1 million acres. Ad- Associated national forest: Tongass miralty Island has been the home to the Tlingít people for approximately 10,000 years. The monument area continues Total Forest Service acres: 997,226 to provide subsistence for these Alaskan Natives. Angoon, Reasons designated: “archaeological, cultural, and Admiralty Island’s only permanent community, continues historical resources, ecological and scientific value” to be an important cultural base. (Presidential Proclamation, 1978) BACKGROUND The Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act (ANSCA) of 1971 honored the rights of Alaska Natives to select approxi- People and visitors mately 44 million acres of Federal land in Alaska and au- thorized the Secretary of the Interior to withdraw 80 mil- Nearest metropolitan area: no metro areas within lion acres of land to be studied for possible additions to 500 miles the National Park, Wildlife Refuge, Wild and Scenic Rivers, and National Forest systems. -

Food Habits of Brown Bears on Northern Admiralty Island In

FOOD HABITS OF BROWN BEARS ON NORTHERN ADMl,RALTY · I SLANP. , SOUTHEAST.~LASKA ·A THESIS. Presented -to ~he Faculty of the University of Alaska in Partial Fulfillment o·f the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENGE By Thomas M. McCarthy,· }).S. F.iirbanks; Alaska December-1989 FOOD HAB~TS OF BROWN BEARS ON NORTHERN ADMIRALTY ISLAND, SOUTHEAST ALASKA By Thomas Michael McCarthy RECOMMENDED: APPROVED: FOOD HAB.rrs ()F B~QWN BEARS ON NORTHERN A1)~~llAL'J:'Y ··IS.LANl;);. SOtrrliEA&T .'~S~· ·A THESIS Presented ·tro 'the Faculty of the University of Alaska in Partial Fulfillment o£ the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENGE By Thomas.M. McCarthy,· ~.s. Fairbanks, ·Alaska · D~cember·1989 ABSTRACT The food habits of brown bears on northern Admiralty Island in Southeast Alaska were studied through analysis of fecal samples collected in 1984 and 1985. The diets of two groups of bears were examined, those that used low elevation habitats and anadromous fish streams, and those that remained at higher elevations throughout the year. Selected forage items observed in the diets were analyzed for nutrient content. While most bears used the protein-rich salmon resource, bears at high elevations substituted deer, small mammals, and plant species and parts high in nitrogen. Both groups of bears appeared to seek a high energy diet during the fall pre-denning period. In the second phase of the study, captive brown bears were used in feeding trials to determine the digestibilities of 4 natural forages; sedge (Garex lyngbyaei), skunk cabbage (Lysichitum americanum), devil's club berries (Oplopanax horridus), and salmon (Oncorhynchus sp.). -

Inferring Ancestry Across Hybrid Genomes Using Low-Coverage Sequence Data

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Previously Published Works Title AD-LIBS: inferring ancestry across hybrid genomes using low-coverage sequence data. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/04j576r0 Journal BMC bioinformatics, 18(1) ISSN 1471-2105 Authors Schaefer, Nathan K Shapiro, Beth Green, Richard E Publication Date 2017-04-04 DOI 10.1186/s12859-017-1613-0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Schaefer et al. BMC Bioinformatics (2017) 18:203 DOI 10.1186/s12859-017-1613-0 SOFTWARE Open Access AD-LIBS: inferring ancestry across hybrid genomes using low-coverage sequence data Nathan K. Schaefer1,3*, Beth Shapiro2,3 and Richard E. Green1,3 Abstract Background: Inferring the ancestry of each region of admixed individuals’ genomesisusefulinstudiesranging from disease gene mapping to speciation genetics. Current methods require high-coverage genotype data and phased reference panels, and are therefore inappropriate for many data sets. We present a software application, AD-LIBS, that uses a hidden Markov model to infer ancestry across hybrid genomes without requiring variant calling or phasing. This approach is useful for non-model organisms and in cases of low-coverage data, such as ancient DNA. Results: We demonstrate the utility of AD-LIBS with synthetic data. We then use AD-LIBS to infer ancestry in two published data sets: European human genomes with Neanderthal ancestry and brown bear genomes with polar bear ancestry. AD-LIBS correctly infers 87–91% of ancestry in simulations and produces ancestry maps that agree with published results and global ancestry estimates in humans. In brown bears, we find more polar bear ancestry than has been published previously, using both AD-LIBS and an existing software application for local ancestry inference, HAPMIX. -

Auke Lake Watershed Assessment Auke Lake Watershed in Juneau, Alaska

Auke Lake Watershed Assessment Auke Lake Watershed in Juneau, Alaska Prepared by the Juneau Watershed Partnership April 2009 The Juneau Watershed Partnership (JWP) is a nonprofit organization whose mission is to promote watershed integrity in the City and Borough of Juneau through education, research, and communication while encouraging sustainable use and development. Statement of Need and Purpose Situated approximately 12 miles north of Juneau, Alaska, Auke Lake is an anadromous system supporting coho, sockeye, pink and chum salmon, as well as cutthroat trout, rainbow trout and Dolly Varden char (Bethers, 1996). The Auke Lake watershed is a popular recreational area for Juneau residents, serves as a backdrop for the University of Alaska-Southeast campus, is a growing residential area, and hosts a NOAA/NMFS research facility on its outlet. The purpose of this watershed assessment is to compile existing data into a single document, in order to identify data gaps and provide recommendations for further studies. This document also provides the City and Borough of Juneau (CBJ) and the public with an overview of the current condition of the Auke Lake watershed, and outlines management recommendations to ensure the sustainability of fish habitat and recreational and aesthetic values. The results of this assessment should be used to guide watershed management of this valuable lake system. The intention is that this report will be utilized by CBJ staff, the CBJ Planning Commission, Wetlands Review Board, the City Assembly, as well as Juneau residents and local, state and federal agencies involved in conservation and land management decisions within the Auke Lake watershed. -

Chapter 3: Brown Bear Management Report. Brown Bear Management

SPECIES Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Wildlife Conservation 907-465-4190 –PO Box 115526 MANAGEMENT REPORT Juneau, AK 99811-5526 CHAPTER 3: BROWN BEAR MANAGEMENT REPORT From: 1 July 2012 To: 30 June 2014 LOCATION 2 GAME MANAGEMENT UNIT: Unit 4 (5,820 mi ) GEOGRAPHIC DESCRIPTION: Admiralty, Baranof, Chichagof, and adjacent islands BACKGROUND Brown bears in Southeast Alaska inhabit all areas in Game Management Unit 4 (including Admiralty, Baranof, Chichagof, Kruzof, Yakobi, and Catherine islands). The population has been isolated from mainland brown/grizzly bear populations for more than 40,000 years and is genetically distinct from other bears (Heaton et al. 1996; Talbot and Shields 1996). Extensive brown bear research has been conducted on Admiralty and Chichagof islands from the early 1980s through 2004 (Schoen and Beier 1990; Titus and Beier 1993; Flynn et al. 2007). Management of Unit 4 brown bears has a colorful and controversial past. In the early part of the twentieth century, there were advocates for both complete elimination of and for more reasonable conservation of brown bears. Market hunting for hides and the calls for elimination of bears were gradually overcome by support for greater protection of the valuable bear resource. As a result, the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G) developed more restrictive harvest regulations for brown bears in Unit 4 (ADF&G 1998). Brown bear sealing requirements were established in Alaska in 1961. Since 1989, hunters have also been required to obtain registration permits before hunting brown bears in Unit 4 (ADF&G 1998). Prior to 1989, hunters were only required to obtain a hunting license and metal-locking big game tag. -

Reconnaissance Geology of Admiralty Island Alaska

Reconnaissance Geology of Admiralty Island Alaska LI By E. H. LATHRAM, J. S. POMEROY, H. C. BERG, and R. A. LONEY ^CONTRIBUTIONS TO GENERAL GEOLOGY GEOLOGICAL SURVEY-BULLETIN 1181-R ^ A reconnaissance study of a geologically -t complex* area in southeast-..--.. Alaska.... UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1965 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STEWART L. UDALL, Secretary X1 GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Thomas B. Nolan, Director Y. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C., 20402 CONTENTS Page Abstract_____________________---_-__-_-__--__-_ _..___.__ Rl Introduction... _______ __-_____-_---_-_ __________ ______ 2 M Geography______________---__---___-_-__--_-_---_ ________ 2 ;._. Previous investigations---..-. ________________________________ 4 Present investigations..-______-_--__ _ ____________________ 6 ^ Tectonic aspects of the geology__-_-__--_--__-_-_______._____.____ 7 Stratigraphy...... _____-___-__--_^---^---^ ----------------------- 10 "-< Silurian(?) rocks_________ . _ 10 Devonian and Devonian(?) rocks--___________-___-______________ 10 J Retreat Group and Gambier Bay Formation___-____-_._ __ 10 ^ Hood Bay Formation..... ............'............ 13 Permian rocks..___-----------------------------------------_-- 14 4 Cannery Formation...__________ _________________________ 14 Pybus Dolomite____---_-_-_-_---_---_---_--__ __________ 16 '>* Undifferentiated Permian and Triassic rocks._____________________ 17 Triassic rocks.__-______________---_---_-_-_---_-----_-________ -

Stephens Passage

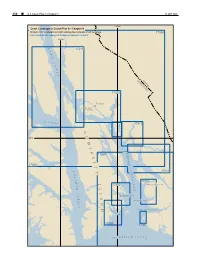

254 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 8, Chapter 9 19 SEP 2021 134°W Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 8—Chapter 9 NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage 17300 http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml 135°W L 17316 Y N N C A N A L UNITED STCANADA ATES 17315 T Juneau E L N DOUGLAS I ISLAND U K A T I C Y S T R A I T 17313 A 17314 D 58°N M I S R T 17360 E A P H L 17300 E T N S C Y 17311 H P A A S T S H 17363 A I A 17362 WINDHAM BAY G M S E L S T GAMBIER BAY A R A HOBART BAY N I T D PYB PORT HOUGHTON US B AY 17363 17365 I C K S O F R E D E R U N D 19 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 8, Chapter 9 ¢ 255 Stephens Passage (1) This chapter describes Stephens Passage, Holkham during the winter, reaching its maximum in January. Bay, Endicott Arm, Tracy Arm, Taku Harbor, Gastineau The least fog occurs during April to July, inclusive, the Channel, Auke Bay, Tee Harbor and the city of Juneau, minimum being in May. including the communities of Douglas and Auke Bay. (10) (2) Ice ENC - US2AK30M (11) Ice is discharged from glaciers in Tracy and Endicott Chart - 16016 Arms, is always found in Holkham Bay and is prevalent in Stephens Passage off the entrance to that bay. -

1 Endemics of Southeast Alaska and Adjacent British Columbia

Endemics of Southeast Alaska and Adjacent British Columbia Common Name Scientific Name Distribution Habitat TNF District ADFG Comments References GMU LICHENS and FUNGI Amygdalaria continua Endemic to southeast Subalpine rocks Geiser et al. (1998) Alaska and Haida Gwaii Amygdalaria haidensis Endemic to southeast Rocky habitats Geiser et al. (1998) Alaska and Haida Gwaii Bryoria carlottae Endemic to BC and Primarily on shore Geiser et al. (1998) southeast Alaska pine and western hemlock in low elevation peatlands and open mixed forests. Bryoria cervinula Endemic to BC and Primarily on open Geiser et al. (1998) southeast Alaska grown shore pine and western hemlock, from low elevations to subalpine. Placopsis roseonigra Endemic to southeast Geiser et al. (1998) Alaska (Sitka, Juneau) and Haida Gwaii Rhizocarpon hensseniae Endemic to southeast On alpine rocks Geiser et al. (1998) Alaska and Haida Gwaii Tremella hypogymniae NW of Haines Lichenicolous fungus Juneau RD GMU 1D Only other NA reports of this species Geiser et al. (1998) on Hypogymnia are from Ontario, Canada physodes. Verrucaria schofieldii Endemic to southeast On littoral rock. Recently described Geiser et al. (1998) Alaska and Haida Gwaii MOSSES Carey small Seligeria careyanna Endemic to Moresby I., Limestone cliffs www.forestbiodive limestone moss Haida Gwaii rsityinbc.ca a peat moss Sphagnum wilfii The type locality of this Pine bogs at low to This species is on the British http://www.efloras. species is in Haida moderate elevations Columbia RED list (endangered or org Gwaii. It has been threatened). collected only infrequently but is fairly common in southeast Alaska. VASCULAR PLANTS upswept moonwart Botrychium ascendens In Alaska, known only Mesic meadows and Yakutat RD GMU 5 Lipkin and Murray from Yakutat and Glacier sandy sites near sea (1997) Bay; elsewhere, from a level. -

Kootznoowoo Wilderness in 1980, the United States Congress Designated 956,255 Acres As the Kootznoowoo Forest Service Alaska Region Wilderness

United States Department of Kootznoowoo Wilderness Agriculture In 1980, the United States Congress designated 956,255 acres as the Kootznoowoo Forest Service Alaska Region Wilderness. Located approximately 15 miles southeast of Juneau and encompassed by Admiralty Island National Monument on Admiralty Island, the Kootznoowoo Tongass National Forest Wilderness is primary accessed by boats or floatplanes but canoes and kayaks can also Admiralty National Monument be used. With its salmon-filled creeks, hundreds of spectacular mountain lakes, and 8510 Mendenhall Loop Road towering alpine peaks, Kootznoowoo can provide for the ultimate wilderness Juneau, AK 99801 experience. It is strategically managed to continue the preservation of this undeveloped, enduring ecosystem for the enjoyment of present and future generations. Phone: (907) 586-8800 Fax: (907) 586-8808 Wilderness Laws www.fs.fed.us/r10/tongass The Wilderness Act, ANILCA, and the Tongass Land and Resource Management Plan of 2008 (TLMP) give direction to designated wilderness areas in the Tongass National Forest. The Wilderness Act, ANILCA and TLMP prohibit the following: ♦ Commercial enterprise (except for outfitters and guides) ♦ Permanent and temporary roads ♦ Use of motor vehicles and motorized equipment (except motorboats, and fixed wing airplanes) ♦ Mechanized form of transport (i.e. bicycles, wheelbarrows) ♦ Damaging of live trees ♦ Construction of structures and installations ♦ Landing of helicopters Wilderness Character Under ANILCA and TLMP temporary Walk carefully here. The Tlingit people of Southeast Alaska have structures are allowed but are limited to a 14- long known that brown bears outnumber people by a large margin day stay at any one location. TLMP also in the rainforest island wilderness known as Kootznoowoo, the mandates a group size limit of no more “bear fort.” Here the brown bear confronts us with our fear of the than 12 persons for commercial or general primeval forest and serves as an ambassador for all things wild. -

Alexander Archipelago Wolf: a Conservation Assessment

United States Department of Agriculture The Alexander Archipelago Forest Service Wolf: A Conservation Pacific Northwest Research Station Assessment General Technical Report PNW-GTR-384 David K. Person, Matthew Kirchhoff, November 1996 Victor Van Ballenberghe, George C. Iverson, and Edward Grossman Authors DAVID K. PERSON is a graduate fellow, Alaska Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, AK 99775; MATTHEW KIRCHHOFF is a research wildlife biologist, Alaska Department of Fish and Game, P.O. Box 240020 Douglas, AK 99824; VICTOR VAN BALLENBERGHE is a research wildlife biologist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, Forestry Sciences Laboratory, 3301 C Street, Suite 200, Anchorage, AK 99503-3954; GEORGE C. IVERSON is the regional ecology program leader, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Alaska Region, P.O. Box 21628, Juneau, AK 99801; and EDWARD GROSSMAN is a wildlife biologist with the U.S. Department of the Interior, Ecological Services, 3000 Vintage Boulevard Suite 205, Juneau, AK 99801. Conservation and Resource Assessments for the Tongass Land Management Plan Revision Charles G. Shaw III Technical Coordinator The Alexander Archipelago Wolf: A Conservation Assessment David K. Person Matthew Kirchhoff Victor Van Ballenberghe George C. Iverson Edward Grossman Published by: U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station Portland, Oregon General Technical Report PNW-GTR-384 November 1996 In cooperation with: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Alaska Department of Fish and Game Abstract Person, David K.; Kirchhoff, Matthew; Van Ballenberghe, Victor; Iverson, George C.; Grossman, Edward. 1996. The Alexander Archipelago wolf: a conservation assessment.