Listening to the Campanaccio of San Mauro Forte

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

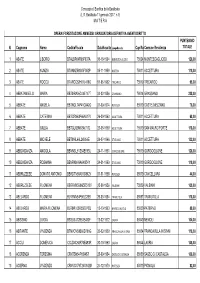

1-Graduatoria Definitiva Operai Aventi Diritto

Consorzio di Bonifica della Basilicata (L.R. Basilicata 11 gennaio 2017, n.1) M A T E R A OPERAI FORESTAZIONE AMMESSI: GRADUATORIA DEFINITIVA AVENTI DIRITTO PUNTEGGIO N. Cognome Nome CodiceFiscale DataNascita LuogoNascita Cap ResidenzaComune Residenza TOTALE 1 ABATE LIBORIO BTALBR64R06F637A 06-10-1964 MONTESCAGLIOSO 75024 MONTESCAGLIOSO 128,00 2 ABATE NUNZIA BTANNZ59S45F052P 05-11-1959 MATERA 75011 ACCETTURA 118,00 3 ABATE ROCCO BTARCC62H01L418O 01-06-1962 TRICARICO 75019 TRICARICO 98,00 4 ABBATANGELO MARIA BBTMRA56C44E147T 04-03-1956 GRASSANO 75014 GRASSANO 228,00 5 ABBATE ANGELA BBTNGL74P41G942O 01-09-1974 POTENZA 85010 CASTELMEZZANO 76,00 6 ABBATE CATERINA BBTCRN63P66A017V 26-09-1963 ACCETTURA 75011 ACCETTURA 68,00 7 ABBATE GIULIA BBTGLI69M63A017D 23-08-1969 ACCETTURA 75010 SAN MAURO FORTE 118,00 8 ABBATE MICHELE BBTMHL66L24I954E 24-07-1966 STIGLIANO 75011 ACCETTURA 132,00 9 ABBONDANZA ANGIOLA BBNNGL61S64E093U 24-11-1961 GORGOGLIONE 75010 GORGOGLIONE 128,00 10 ABBONDANZA ROSANNA BBNRNN69A64I954Y 24-01-1969 STIGLIANO 75010 GORGOGLIONE 118,00 11 ABBRUZZESE DONATO ANTONIO BBRDTN68A01G942V 01-01-1968 POTENZA 85010 CANCELLARA 44,00 12 ABBRUZZESE FILOMENA BBRFMN56M65D513V 25-08-1956 VALSINNI 75029 VALSINNI 108,00 13 ABELARDO FILOMENA BLRFMN54P66L326B 26-09-1954 TRAMUTOLA 85057 TRAMUTOLA 118,00 14 ABELARDO MARIA FILOMENA BLRMFL63R55E976Q 15-10-1963 MARSICO NUOVO 85050 PATERNO 88,00 15 ABISSINO LUIGIA BSSLGU72B53E483F 13-02-1972 LAURIA 85040 NEMOLI 104,00 16 ABITANTE VINCENZA BTNVCN59B66D766G 26-02-1959 FRANCAVILLA IN SINNI 85034 FRANCAVILLA IN SINNI 118,00 17 ACCILI DOMENICA CCLDNC60R70E483R 30-10-1960 LAURIA 85044 LAURIA 148,00 18 ACERENZA TERESINA CRNTSN54P65I457I 25-09-1954 SASSO DI CASTALDA 85050 SASSO DI CASTALDA 108,00 19 ACIERNO VINCENZO CRNVCN79T24G942M 24-12-1979 POTENZA 85010 PIGNOLA 82,00 Consorzio di Bonifica della Basilicata (L.R. -

Comune Di San Mauro Forte Provincia Di Matera

COMUNE DI SAN MAURO FORTE PROVINCIA DI MATERA STRADA DI COLLEGAMENTO SAN MAURO FORTE CAVONICA Progetto di completamento per l'adeguamento della ex Strada Comunale DATA: PROGETTO PRELIMINARE Ottobre 2020 TAVOLA N. H RELAZIONE PAESAGGISTICA SCALA STUDIO PRELIMINARE AMBIENTALE IL PROGETTISTA IL RESPONSABILE DEL PROCEDIMENTO Arch. Rosario RACANIELLO Ing. Domenico TERRANOVA PROVINCIA DI MATERA --------------------------------------------------------- Area Tecnica Strada di collegamento San Mauro Forte – Cavonica Progetto di completamento per l’adeguamento della ex Strada Comunale RELAZIONE PAESAGGISTICA 1. PREMESSA La presente relazione paesaggistica, redatta ai sensi del “Codice dei Beni Culturali e del Paesaggio” di cui al D.P.C.M. 12/12/2005, a corredo del progetto relativo al progetto denominato «Strada di collegamento San Mauro Forte – Cavonica- Progetto di completamento per l’adeguamento della ex Strada Comunale» e contiene tutti gli elementi necessari alla verifica della compatibilità paesaggistica dell’intervento, con riferimento ai contenuti dei piani paesaggistici ovvero dei piani urbanistico-territoriali con specifica considerazione dei valori paesaggistici. A tal fine la relazione, dotata di specifica autonomia d’indagine, fa riferimento agli elaborati tecnici redatti per motivare ed evidenziare la qualità dell’intervento in relazione al suo contesto. 2. INQUADRAMENTO SOCIO – ECONOMICO DELL’OPERA NEL CONTESTO TERRITORIALE La strada in progetto consentirà di ridurre l’isolamento infrastrutturale di una parte del territorio montano della Provincia di Matera ed in particolare del comune di San Mauro Forte mettendolo in comunicazione con alcuni degli assi viari più importanti della regione (Bradanica, Basentana, Saurina e Fondovalle dell’Agri). Il tracciato di progetto si svilupperà nel territorio amministrativo del Comune di San Mauro Forte in provincia di Matera. -

Medici Convenzionati Con La ASM Elencati Per Ambiti Di Scelta

DIPARTIMENTO CURE PRIMARIE S.S. Organizzazione Assistenza Primaria MMG, PLS, CA Medici Convenzionati con la ASM Elencati per Ambiti di Scelta Ambito : Accettura - Aliano - Cirigliano - Gorgoglione - San Mauro Forte - Stigliano 80 DEFINA/DOMENICA Accettura VIA IV NOVEMBRE 63 bis 63 bis 9930 SARUBBI/ANTONELLA STIGLIANO Corso Vittorio Emanuele II 45 308 SANTOMASSIMO/LUIGINA MIRIAM Aliano VIA DELLA VITTORIA 4 8794 MORMANDO/ANTONIO Cirigliano VIA FONTANA 8 8794 MORMANDO/ANTONIO Gorgoglione via DE Gasperi 30 3 BELMONTE/ROCCO San Mauro Forte VIA FRATELLI CATALANO 5 4374 MANDILE/FRANCESCO San Mauro Forte CORSO UMBERTO I 14 4242 CASTRONUOVO/ANTONIO Stigliano CORSO UMBERTO 57 8474 DIGILIO/MARGHERITA CARMELA Stigliano Corso Umberto I° 29 9382 DIRUGGIERO/MARGHERITA Stigliano Via Zanardelli 58 Ambito : Bernalda 9292 CALBI/MARISA Bernalda VIALE EUROPA - METAPONTO 10 9114 CARELLA/GIOVANNA Bernalda VIA DEL CONCILIO VATICANO II 35 8523 CLEMENTELLI/GREGORIO Bernalda CORSO UMBERTO 113 7468 GRIECO/ANGELA MARIA Bernalda VIALE BERLINGUER 15 7708 MATERI/ANNA MARIA Bernalda PIAZZA PLEBISCITO 4 9283 PADULA/PIETRO SALVATORE Bernalda VIA MONTESCAGLIOSO 28 9698 QUINTO/FRANCESCA IMMACOLATA Bernalda Via Nuova Camarda 24 4366 TATARANNO/RAFFAELE Bernalda CORSO UMBERTO 113 327 TOMASELLI/ISABELLA Bernalda CORSO UMBERTO 113 9918 VACCARO/ALMERINDO Bernalda CORSO UMBERTO 113 8659 VITTI/MARIA ANTONIETTA Bernalda VIA TRIESTE 14 Ambito : Calciano - Garaguso - Oliveto Lucano - Tricarico MEDICO INCARICATO Calciano DISTRETTO DI CALCIANO S.N.C. MEDICO INCARICATO Oliveto Lucano -

Exploring the Case of Matera, 2019 European Capital of Culture

Tourism consumption and opportunity for the territory: Exploring the case of Matera, 2019 European Capital of Culture Fabrizio Baldassarre, Francesca Ricciardi, Raffaele Campo Department of Economics, Management and Business Law, University of Bari (Italy) email: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract Purpose. Matera is an ancient city, located in the South of Italy and known all over the world for the famous Sassi; the city has been recently seen an increasing in flows of tourism thanks to its nomination to acquire the title of 2019 European Capital of Culture in Italy. The aim of the present work is to investigate about the level of services offered to tourists, the level of satisfaction, the possible improvements and the weak points to strengthen in order to realize a high service quality, to stimulate new behaviours and increase the market demand. Methodology. The methodology applied makes reference to an exploratory study conducted with the content analysis; the information is collected through a questionnaire submitted to a tourist sample, in cooperation with hotel and restaurant associations, museums, and public/private tourism institutions. Findings. First results show how important is to study the relationship between the supply of services and tourists behaviour to create value through the identification of improving situations, suggesting the rapid adoption of corrective policies which allow an economic return for the territory. Practical implications. It is possible to realize a competitive advantage analyzing the potentiality of the city to attract incoming tourism, the level of touristic attractions, studying the foreign tourist’s behaviour. Originality/value. -

ONORATI BENIAMINO MARIO Via San

F ORMATO EUROPEO PER IL CURRICULUM V I T A E INFORMAZIONI PERSONALI Nome ONORATI BENIAMINO MARIO Indirizzo Via San Giovanni, 20 – 75010 Oliveto Lucano (Matera) Telefono 328-3166716 Fax E-mail [email protected]; [email protected] Nazionalità Italiana Data di nascita 11.07.1971 ESPERIENZA LAVORATIVA • Data dal 15 maggio 2012 • Nome e indirizzo del datore di Università degli Studi della Basilicata - Potenza lavoro • Tipo di azienda o settore Ente Pubblico • Tipo di impiego Assunto a tempo pieno ed indeterminato presso il Dipartimento Tecnico-Economico per la Gestione del Territorio Agricolo e Forestale. Dal 6 agosto 2012 assegnazione, con Provvedimento del Direttore Amministrativo n. 237 , alla Scuola di Ingegneria – Settore Gestione della Ricerca e, con Provvedimento del Direttore della Scuola di Ingegneria n. 68/2013 del 15 maggio 2013 , successiva assegnazione al Laboratorio di Idraulica e Costruzioni Idrauliche. • Principali mansioni e responsabilità • svolgimento di funzione specialistica in qualità di Responsabile nell’ambito del Laboratorio; • conduzione e gestione di grandi attrezzature e di un insieme di attrezzature complesse quali due canalette a pendenza variabile, una canaletta a pendenza fissa, un’area per modelli fisici a grande scala, una installazione per lo studio dei moti di filtrazione ed infiltrazione in mezzi porosi, un’installazione per la simulazione delle piogge e per la formazione delle reti idrografiche naturali, oltre a banchi idraulici didattici; • svolgimento, in autonomia, di servizi che -

SAN MAURO FORTE E SALANDRA (MT)

PROGETTO PER LA REALIZZAZIONE DI UN PARCO EOLICO Comuni di SAN MAURO FORTE e SALANDRA (MT) Località Serre Alte e Serre d’olivo A. PROGETTO DEFINITIVO DELL’IMPIANTO, DELLE OPERE CONNESSE E DELLE INFRASTRUTTURE INDISPENSABILI OGGETTO Codice: SMF Autorizzazione Unica ai sensi del D.Lgs 387/2003 e D.Lgs 152/2006 N° Elaborato: Piano di Caratterizzazione Ambientale A.18 Tipo documento Data Progetto definitivo Luglio 2019 Progettazione Progettisti Ing. Vassalli Quirino Proponente ITW San Mauro Forte Srl Via del Gallitello 89 | 85100 Potenza (PZ) P.IVA 02053100760 Ing. Speranza Carmine Antonio Rappresentante legale Emmanuel Macqueron REVISIONI Rev. Data Descrizione Elaborato Controllato Approvato 00 Luglio 2019 Emissione AM QV/AS/DR Quadran Italia Srl SMF_A.18_ Piano di Caratterizzazione Ambientale.doc SMF_A.18_ Piano di Caratterizzazione Ambientale.pdf Il presente elaborato è di proprietà di ITW San Mauro Forte S.r.l. Non è consentito riprodurlo o comunque utilizzarlo senza autorizzazione di San Mauro Forte S.r.l. ITW San Mauro Forte S.r.l. • Via del Gallitello, 89 • 85100 Potenza (PZ)• Italia P.IVA 02053100760 • [email protected] • [as,qv][am] SMF_A18_Piano Caratterizzazione Ambientale.doc 190730 ____________________ INDICE PREMESSA ........................................................................................ 4 1. DATI GENERALI DEL PROGETTO ......................................................... 5 1.1 DESCRIZIONE GENERALE DELL’OPERA ............................................................ 5 1.2 UBICAZIONE DEI SITI D’INTERVENTO -

Annata Venatoria 2019 / 2020 - Elenco Di Ammissione Dei Cacciatori Residenti E Domiciliati Nell'ambito: Atc A

ATC 2 POTENZA - ANNATA VENATORIA 2019 / 2020 - ELENCO DI AMMISSIONE DEI CACCIATORI RESIDENTI E DOMICILIATI NELL'AMBITO: ATC A Nro. provincia provincia provincia porto d'armi cognome nome data nascita comune nascita comune residenza comune domicilio porto d'armi questura attesa rilascio Ordine nascita residenza domicilio rilascio 1 ATTANASIO PASQUALE 25/07/1953 NOCERA SUPERIORE SA POMARICO MT POMARICO MT 04/06/2013 722793-n NOCERA INFERIORE 2 BELMONTE FERDINANDO 06/04/1984 STIGLIANO MT ACCETTURA MT ACCETTURA MT 22/05/2013 645791-N MATERA 3 BENEDETTO ANDREA 15/05/1990 PISTICCI MT BERNALDA MT BERNALDA MT 18/07/2014 176130-O MATERA 4 BRANDA PIETRO 01/02/1973 ACCETTURA MT ACCETTURA MT ACCETTURA MT 24/06/2015 529577-O MATERA 5 BRANDA VINCENZO 23/07/1979 ACCETTURA MT ACCETTURA MT 25/05/2018 770494-O MATERA 6 CALBI AUGUSTO 26/04/1959 TRICARICO MT MATERA MT MATERA MT 09/05/2017 770157-O MATERA 7 CALVELLO CATALDO 13/11/1949 IRSINA MT IRSINA MT IRSINA MT 11/01/2019 173375-P MATERA 8 CALVIELLO TEODORO 28/05/1967 MIGLIONICO MT MIGLIONICO MT MIGLIONICO MT 31/08/2015 615526-O MATERA 9 CANDELA GIUSEPPE 26/10/1973 BARI BA IRSINA MT IRSINA MT 10/10/2017 770335-O MATERA 10 CANSONIERE GIOVANNI 29/07/1949 IRSINA MT IRSINA MT IRSINA MT 25/05/2015 407615-O MATERA 11 CAPPIELLO GIUSEPPE 05/06/1981 BARI BA IRSINA MT IRSINA MT 01/08/2018 770566-O MATERA SAN GIORGIO A 12 CASTALDO LUIGI 10/10/1943 NA POMARICO MT POMARICO MT 20/07/2015 301851-0 MATERA CREMANO 13 CAVALCANTE SALVATORE 30/04/1969 TRICARICO MT CALCIANO MT CALCIANO MT 12/05/2015 529581-N MATERA 14 CENTONZE -

SEDI ASSEGNATE-Signed

Ministero dell’Istruzione UFFICIO SCOLASTICO REGIONALE PER LA BASILICATA Ufficio IV – Ambito territoriale di Matera Area I U.O. 2 – “Personale ATA” Resp. del procedimento: Aliotta Resp. dell’istruttoria: Vicenti Tel.: 0835 – 315243 -Tel.: 0835 – 315236 e-mail: [email protected] Procedura selettiva per l’internalizzazione dei servizi D.M. 1074/2019 e D.D. 2200/2019. SEDI SCELTE DAL PERSONALE CONVOCATO IL 27.2.2020 PER NOMINA A TEMPO INDETERMINATO PROFILO: COLLABORATORI SCOLASTICI N. POSTI SEDI ASSEGNATE NOMINATIVI MTIC82400V 1 MIGLIO LUCA I.C. MINOZZI – FESTA. MATERA MTIC82400V 2 GUGLIELMUCCI SALVATORE I.C. MINOZZI – FESTA. MATERA MTIC82400V 3 PIRRETTI ARGENZIA I.C. MINOZZI – FESTA. MATERA MTIC82400V 4 LOMONACO PALMA I.C. MINOZZI – FESTA. MATERA MTIC82500P 1 PAOLICELLI CHIARA ROSA I.C. TORRACA - MATERA MTIC82500P 2 // I.C. TORRACA- MATERA MTIC82700A 1 SANTERAMO MARIA I.C. PASCOLI - MATERA Via Lucana 194 – 75100 MATERA – Pec: [email protected] - E-mail: [email protected] Url: www.istruzionematera.it - Tel. 0835/3151 - C.F. e P.IVA: 80001420779 Ministero dell’Istruzione UFFICIO SCOLASTICO REGIONALE PER LA BASILICATA Ufficio IV – Ambito territoriale di Matera MTIC82700A 2 RONDINONE COSIMO DAMIANO I.C. PASCOLI - MATERA MTIC82700A 3 MARTINELLI LUCIA I.C. PASCOLI - MATERA MTIC82700A 4 MARTINELLI MICHELINA I.C. PASCOLI - MATERA MTIC828006 1 VENTURO CARMENIO I.C. FERMI - MATERA MTIC829002 1 CARLUCCI PATRIZIA I.C. N. 6 BRAMANTE - MATERA MTIC80900R 1 COLETTA MADDALENA I.C. IRSINA MTIC80900R 2 MANGIERI DONATA I.C. IRSINA MTIC80900R 3 MASCOLO MARIO I.C. IRSINA MTIC80900R 4 PACI VINCENZA I.C. IRSINA MTIC82100B 1 MIRAGLIA PANCRAZIO I.C. -

A Collaborative Decision-Making Process for Cultural Heritage Enhancement

sustainability Article From Place-Branding to Community-Branding: A Collaborative Decision-Making Process for Cultural Heritage Enhancement Gaia Daldanise Institute of Research on Innovation and Services for Development (IRISS), National Research Council of Italy (CNR), 80134 Naples, Italy; [email protected]; Tel.: +39-081-247-0995 Received: 30 October 2020; Accepted: 10 December 2020; Published: 12 December 2020 Abstract: The international debate on cultural heritage enhancement and cultural cross-overs, highlights the need to rethink the relationship between economy, society and territory by working on innovative urban planning and evaluation approaches. In recent times, the concept of “place branding” has become widespread in strategic urban plans, linking marketing approaches to the attractive features of places. The purpose of this study is to outline a holistic approach to cultural heritage enhancement for urban regeneration based on creative and collaborative place branding: “Community branding”. The methodology was tested in Pisticci—near Matera (Basilicata region, Italy)—starting from its historic center. As a multi-methodological decision-making process, Community branding combines approaches and tools derived from Place Branding, Community Planning, Community Impact Evaluation and Place Marketing. The main results achieved include: an innovative approach that combines both management and planning aspects and empowers communities and skills in network; the co-evaluation of cultural, social and economic impacts for the -

Regione Basilicata Provincia Di Matera Comune Di S. Mauro Forte Documentazione Per Procedura Di Verifica Di Assoggettabilità A

CLIENTE PROGETTISTA COMMESSA CODICE TECNICO 4105827 CODICE VARIANTE VR/16206/006 9106606 LOCALITÀ ODL Contratto Quadro: REGIONE BASILICATA 7200112328 N° 5000002244 del PROVINCIA DI MATERA ELABORATO N° 06.05.2015 COMUNE DI SAN MAURO FORTE (MT) RSV–E –112328_00 PROGETTO FOGLIO REV. Var. Met. All.to Comune di Accettura DN 100 (4") - 75 bar 1 di 84 0 Comune di San Mauro Forte (MT) REGIONE BASILICATA PROVINCIA DI MATERA COMUNE DI S. MAURO FORTE Variante Met. All.to Comune di Accettura DN 100 (4") - 75 bar Comune di San Mauro Forte (MT) DOCUMENTAZIONE PER PROCEDURA DI VERIFICA DI ASSOGGETTABILITÀ A VALUTAZIONE DI IMAPATTO AMBIENTALE (SCREENING) Il progettista Ing. Paolo Marzoli 0 Emissione per permessi. CASOLARO CANNITO MARZOLI OTT. 2016 Rev. Descrizione Elaborato Verificato Approvato Data CLIENTE PROGETTISTA COMMESSA VR/16206/006 PROGETTO Var. Met. All.to Comune di Accettura DN 100 (4") - 75 bar Foglio 2 di 84 Comune di San Mauro Forte (MT) Il presente studio, relativo al progetto relativo alla realizzazione di una variante ad un’esistente metanodotto denominato “All.to Comune di Accettura DN 100 (4") - 75 bar”, di proprietà della Snam Rete Gas S.p.A., all’interno del territorio comunale di San Mauro Forte (MT), è stato redatto ai sensi della L.R. 14 dicembre 1998, n.47” Disciplina della valutazione di impatto ambientale e norme per la tutela dell’ambiente”, facendo particolare riferimento all’allegato B. La variante, di lunghezza complessiva pari a 353 m, si rende necessaria al fine di mettere in sicurezza la condotta ed evitare il ripetersi di fenomeni erosivi che coinvolgano il citato metanodotto. -

Relazione Rev.01 TAV A.Pdf

1 COMUNE DI MONTALBANO JONICO Regione Basilicata PROVINCIA DI MATERA PIANO COMUNALE DI PROTEZIONE CIVILE RELAZIONE GENERALE INDICE INTRODUZIONE PREMESSA E QUADRO NORMATIVO DI RIFERIMENTO 1. LE COMPETENZE DI INDIRIZZO, DI PIANIFICAZIONE ED OPERATIVE 2. LE PROCEDURE DI EMERGENZA 3. IL SISTEMA COMUNALE DI PROTEZIONE CIVILE 3.1 LE COMPONENTI DEL SISTEMA 3.1.1 IL SINDACO 3.1.2 IL COMITATO DI PROTEZIONE CIVILE 3.2 STRUTTURA DI COORDINAMENTO LOCALE 3.3 L'ORGANIZZAZIONE IN FUNZIONI DI SUPPORTO 3.4 IL CENTRO OPERATIVO MISTO 3.5 LE ASSOCIAZIONI DI VOLONTARIATO PRESENTI SUL TERRITORIO 4. OBIETTIVI STRATEGICI ED OPERATIVI DEL PIANO DI PROTEZIONE CIVILE 4.1 IL PIANO DI GESTIONE DELLE EMERGENZE - STRUTTURA 4.1.1 DATI DI BASE E SCENARI DI RISCHIO 4.1.1.1 ANALISI TERRITORIALE 4.1.1.2 GLI SCENARI DI RISCHIO 4.1.1.2.1 Valutazione degli scenari di Rischio Sismico 4.1.1.2.2 Valutazione degli scenari del Rischio Dighe 4.1.1.2.3 Valutazione degli scenari di Rischio Idraulico 4.1.1.2.4 Valutazione degli scenari di Rischio Idrogeologico 4.1.1.2.5 Sistema di allertamento per il rischio idrogeologico d idraulico 4.1.1.2.6 Valutazione degli scenari di Rischio Incendi Boschivi 4.1.2 Individuazione dell' evento calamitoso di progetto 4.1.3 Le aree destinate a scopi di protezione civile 4.2 MODELLO OPERATIVO DI INTERVENTO 4.3 INFORMAZIONE ALLA POPOLAZIONE E FORMAZIONE DEL PERSONALE 4.3.1 Comunicazione propedeutica 4.3.2 Informazione preventiva 4.3.3 Informazione in emergenza 4.3.4 Programma scuole 4.3.5 Formazione del personale 5. -

Scarica Lo Statuto Di Oliveto Lucano

Ministero dell'Interno - http://statuti.interno.it C O M U N E D I O L I V E T O L U C A N O STATUTO Delibera n. 11 del 16/5/2005. TITOLO I - Principi generali Art. 1 - Autonomia Statutaria 1. Il Comune di Oliveto Lucano è Ente locale autonomo, rappresenta la propria comunità, ne cura gli interessi e ne promuove lo sviluppo. 2. Il Comune si avvale della sua autonomia, nel rispetto della Costituzione, dei regolamenti comunitari e dei principi generali dell’ordinamento, per lo sviluppo della propria attività ed il perseguimento dei suoi fini istituzionali. 3. Il Comune di Oliveto Lucano riconosce e fa proprio il principio di sussidiarietà, sancito dal Trattato dell’Unione Europea di Maastricht. Esso è un fondamentale riferimento di libertà e di democrazia, cardine della nostra concezione dello Stato. 4. Il Comune rappresenta la comunità di Oliveto Lucano nei rapporti con lo Stato, con la Regione Basilicata, con la Provincia e con gli altri enti o soggetti pubblici e privati e, nell’ambito degli obiettivi indicati nel presente statuto, nei confronti della comunità internazionale. Art. 2 – Finalità 1. Il Comune promuove lo sviluppo e il progresso civile, sociale ed economico della Comunità di Oliveto Lucano ispirandosi ai valori ed agli obiettivi della Costituzione, della Carta Europea delle Autonomie Locali e della Dichiarazione Universale dei diritti dell’uomo. 2. Il Comune ricerca la collaborazione e la cooperazione con gli altri soggetti pubblici e privati e promuove la partecipazione dei singoli cittadini, delle associazioni e delle forze sociali ed economiche all’attività amministrativa.