A Collaborative Decision-Making Process for Cultural Heritage Enhancement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

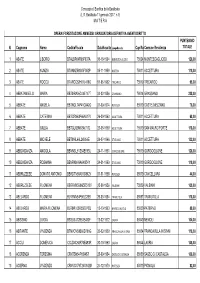

1-Graduatoria Definitiva Operai Aventi Diritto

Consorzio di Bonifica della Basilicata (L.R. Basilicata 11 gennaio 2017, n.1) M A T E R A OPERAI FORESTAZIONE AMMESSI: GRADUATORIA DEFINITIVA AVENTI DIRITTO PUNTEGGIO N. Cognome Nome CodiceFiscale DataNascita LuogoNascita Cap ResidenzaComune Residenza TOTALE 1 ABATE LIBORIO BTALBR64R06F637A 06-10-1964 MONTESCAGLIOSO 75024 MONTESCAGLIOSO 128,00 2 ABATE NUNZIA BTANNZ59S45F052P 05-11-1959 MATERA 75011 ACCETTURA 118,00 3 ABATE ROCCO BTARCC62H01L418O 01-06-1962 TRICARICO 75019 TRICARICO 98,00 4 ABBATANGELO MARIA BBTMRA56C44E147T 04-03-1956 GRASSANO 75014 GRASSANO 228,00 5 ABBATE ANGELA BBTNGL74P41G942O 01-09-1974 POTENZA 85010 CASTELMEZZANO 76,00 6 ABBATE CATERINA BBTCRN63P66A017V 26-09-1963 ACCETTURA 75011 ACCETTURA 68,00 7 ABBATE GIULIA BBTGLI69M63A017D 23-08-1969 ACCETTURA 75010 SAN MAURO FORTE 118,00 8 ABBATE MICHELE BBTMHL66L24I954E 24-07-1966 STIGLIANO 75011 ACCETTURA 132,00 9 ABBONDANZA ANGIOLA BBNNGL61S64E093U 24-11-1961 GORGOGLIONE 75010 GORGOGLIONE 128,00 10 ABBONDANZA ROSANNA BBNRNN69A64I954Y 24-01-1969 STIGLIANO 75010 GORGOGLIONE 118,00 11 ABBRUZZESE DONATO ANTONIO BBRDTN68A01G942V 01-01-1968 POTENZA 85010 CANCELLARA 44,00 12 ABBRUZZESE FILOMENA BBRFMN56M65D513V 25-08-1956 VALSINNI 75029 VALSINNI 108,00 13 ABELARDO FILOMENA BLRFMN54P66L326B 26-09-1954 TRAMUTOLA 85057 TRAMUTOLA 118,00 14 ABELARDO MARIA FILOMENA BLRMFL63R55E976Q 15-10-1963 MARSICO NUOVO 85050 PATERNO 88,00 15 ABISSINO LUIGIA BSSLGU72B53E483F 13-02-1972 LAURIA 85040 NEMOLI 104,00 16 ABITANTE VINCENZA BTNVCN59B66D766G 26-02-1959 FRANCAVILLA IN SINNI 85034 FRANCAVILLA IN SINNI 118,00 17 ACCILI DOMENICA CCLDNC60R70E483R 30-10-1960 LAURIA 85044 LAURIA 148,00 18 ACERENZA TERESINA CRNTSN54P65I457I 25-09-1954 SASSO DI CASTALDA 85050 SASSO DI CASTALDA 108,00 19 ACIERNO VINCENZO CRNVCN79T24G942M 24-12-1979 POTENZA 85010 PIGNOLA 82,00 Consorzio di Bonifica della Basilicata (L.R. -

Medici Convenzionati Con La ASM Elencati Per Ambiti Di Scelta

DIPARTIMENTO CURE PRIMARIE S.S. Organizzazione Assistenza Primaria MMG, PLS, CA Medici Convenzionati con la ASM Elencati per Ambiti di Scelta Ambito : Accettura - Aliano - Cirigliano - Gorgoglione - San Mauro Forte - Stigliano 80 DEFINA/DOMENICA Accettura VIA IV NOVEMBRE 63 bis 63 bis 9930 SARUBBI/ANTONELLA STIGLIANO Corso Vittorio Emanuele II 45 308 SANTOMASSIMO/LUIGINA MIRIAM Aliano VIA DELLA VITTORIA 4 8794 MORMANDO/ANTONIO Cirigliano VIA FONTANA 8 8794 MORMANDO/ANTONIO Gorgoglione via DE Gasperi 30 3 BELMONTE/ROCCO San Mauro Forte VIA FRATELLI CATALANO 5 4374 MANDILE/FRANCESCO San Mauro Forte CORSO UMBERTO I 14 4242 CASTRONUOVO/ANTONIO Stigliano CORSO UMBERTO 57 8474 DIGILIO/MARGHERITA CARMELA Stigliano Corso Umberto I° 29 9382 DIRUGGIERO/MARGHERITA Stigliano Via Zanardelli 58 Ambito : Bernalda 9292 CALBI/MARISA Bernalda VIALE EUROPA - METAPONTO 10 9114 CARELLA/GIOVANNA Bernalda VIA DEL CONCILIO VATICANO II 35 8523 CLEMENTELLI/GREGORIO Bernalda CORSO UMBERTO 113 7468 GRIECO/ANGELA MARIA Bernalda VIALE BERLINGUER 15 7708 MATERI/ANNA MARIA Bernalda PIAZZA PLEBISCITO 4 9283 PADULA/PIETRO SALVATORE Bernalda VIA MONTESCAGLIOSO 28 9698 QUINTO/FRANCESCA IMMACOLATA Bernalda Via Nuova Camarda 24 4366 TATARANNO/RAFFAELE Bernalda CORSO UMBERTO 113 327 TOMASELLI/ISABELLA Bernalda CORSO UMBERTO 113 9918 VACCARO/ALMERINDO Bernalda CORSO UMBERTO 113 8659 VITTI/MARIA ANTONIETTA Bernalda VIA TRIESTE 14 Ambito : Calciano - Garaguso - Oliveto Lucano - Tricarico MEDICO INCARICATO Calciano DISTRETTO DI CALCIANO S.N.C. MEDICO INCARICATO Oliveto Lucano -

Exploring the Case of Matera, 2019 European Capital of Culture

Tourism consumption and opportunity for the territory: Exploring the case of Matera, 2019 European Capital of Culture Fabrizio Baldassarre, Francesca Ricciardi, Raffaele Campo Department of Economics, Management and Business Law, University of Bari (Italy) email: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract Purpose. Matera is an ancient city, located in the South of Italy and known all over the world for the famous Sassi; the city has been recently seen an increasing in flows of tourism thanks to its nomination to acquire the title of 2019 European Capital of Culture in Italy. The aim of the present work is to investigate about the level of services offered to tourists, the level of satisfaction, the possible improvements and the weak points to strengthen in order to realize a high service quality, to stimulate new behaviours and increase the market demand. Methodology. The methodology applied makes reference to an exploratory study conducted with the content analysis; the information is collected through a questionnaire submitted to a tourist sample, in cooperation with hotel and restaurant associations, museums, and public/private tourism institutions. Findings. First results show how important is to study the relationship between the supply of services and tourists behaviour to create value through the identification of improving situations, suggesting the rapid adoption of corrective policies which allow an economic return for the territory. Practical implications. It is possible to realize a competitive advantage analyzing the potentiality of the city to attract incoming tourism, the level of touristic attractions, studying the foreign tourist’s behaviour. Originality/value. -

Listening to the Campanaccio of San Mauro Forte

SOUNDMASKS IN 2 RESOUNDING PLACES: LISTENING TO THE CAMPANACCIO OF SAN MAURO FORTE Nicola Scaldaferri This chapter concerns the nocturnal parade of carriers of large cow- bells in San Mauro Forte, a village of 1400 inhabitants, at 540m above sea level, within the hilly region west of the town of Matera. This event offers the opportunity to explore some crucial issues discussed in this book, in particular the role of sound in creating a sense of community beyond its symbolic functions, the function of rhythm and bodily involvement in the creation of a group identity, the relationship between sound and the space of the village where the event takes place, and the occurrence over time of processes of heritagisation. In response to the primarily sonorous qualities of this event, listening has been a principal research method. In contrast to what usually happens in other rituals involving bells around the period of Carnival in Europe, in San Mauro the cowbells are not used to create a clash of chaotic clangs but rather a series of regular rhythmic sequences. The participants wear a costume but do not mask their faces. In existing research on festivals involving humans and animal bells, the role of face masks and of sonic chaos has always been a central focus of discussion. The case of San Mauro, where both these elements are absent, suggests that sound might take up a masking function, both at an individual and collective level. The sound of each cowbell becomes a soundmask for its carrier, who identifies completely with the sound. At the same time, each carrier’s presence in space and their relationships with others are manifested in the soundscape. -

BASILICATA Thethe Ionian Coast and Itsion Hinterland Iabasilicatan Coast and Its Hinterland a Bespoke Tour for Explorers of Beauty

BASILICATA TheTHE Ionian Coast and itsION hinterland IABASILICATAN COAST and its hinterland A bespoke tour for explorers of beauty Itineraries and enchantment in the secret places of a land to be discovered 2 BASILICATA The Ionian Coast and its hinterland BASILICATA Credit ©2010 Basilicata Tourism Promotion Authority Via del Gallitello, 89 - 85100 POTENZA Concept and texts Vincenzo Petraglia Editorial project and management Maria Teresa Lotito Editorial assistance and support Annalisa Romeo Graphics and layout Vincenzo Petraglia in collaboration with Xela Art English translation of the Italian original STEP Language Services s.r.l. Discesa San Gerardo, 180 – Potenza Tel.: +39 349 840 1375 | e-mail: [email protected] Image research and selection Maria Teresa Lotito Photos Potenza Tourism Promotion Authority photographic archive Basilicata regional department for archaeological heritage photographic archive Our thanks to: Basilicata regional department for archaeological heritage, all the towns, associations, and local tourism offices who made available their photographic archive. Free distribution The APT – Tourism Promotion Authority publishes this information only for outreach purposes and it has been checked to the best of the APT’s ability. Nevertheless, the APT declines any responsibility for printing errors or unintentional omissions. Last update May 2015 3 BASILICATABASILICATA COSTA JONICA The Ionian Coast and its hinterland BASILICATA MATERA POTENZA BERNALDA PISTICCI Start Metaponto MONTALBANO SCANZANO the itinerary POLICORO ROTONDELLA -

ELEZIONI DELLA PROVINCIA DI MATERA.Pdf

PROV//NdAD/,MATERA 1|l?..,'*o.,,,", ELEZIONI DELLA PROVINCIA DI MATERA _ 12 OTTOBRE 2OI4 CANDIDATI ALLA CARICA DI PRESIDENTE CANDIDATO N, 1; STIGLIANO Antonio Mto ! No!! Siri il 09/ | | /1967 - Co^.ìoliere Pmvin.ìale CANDIDATO N. 2: DE GIACOMO Francesco nato r Crotlol. il25101/1968 ,9d,." di GRoTToLE LISTE DEI CAìIDIDATI ALLA CARICA DI CONSIGLIER-E PROVINCIALE LISTA N. I LISTA N. 2 LISTA N. 3 LISTA N. 4 FERRAM Giuseppe BELLACOZZA Teodoro PIERRO Camillo Donato ALBA Cafmine nato a Policoro ìl 29103/1 974 I nato a lÉana il30/04/1971 I rato a Montalbano Jonico il 07/08/1 970 I nato a Metala ii08/11/1955 Considlierc Comúhale di Prot :lcf)Rf| Consiolia/e Conunale di IRSIX^ aonslatB.a Comunate di SoNTALBAì|O JOUCO Corsidt'a.E CoDúnale d, IIATERA UANGIA ELE Antonlo LAIIACCHIA lchele IIODARELLI Glanluca AIIENTA Anna f$aria 2 nato a Tricaico il 29O6/1963 2 nato a Matera il 09/06/1964 2 nato a Policoro ll 19/021942 2 nala a lrsina Í 01r'01/1970 Consiorbrs Conunar€ di Tf,ICARTCO Consiolièto Cohuhala di llÀfER^ Co''s,blr.6 Comunab di POLIGoRO Corsb//'am CoDUn€le d, IRSIIA ftIODARELLI Gluseppe PATERINO Donato lchèle SANSEVERINO Francesco AULETÍA Francesco Antonlo 3 nato a Tursì il 20/06/1 975 3 n6lo a Matora il2&1111956 3 nato a G€ssano il05/081952 3 nato a Ga€guso il28l/11/1950 Cons/o/iere Comff 6re di TURSI Corcialiere Conunah din IZRA Si'|óco d, GRASSANo S,nd66o di GARAGUSO QUINTO Graziantonlo PEPE Mlchele TOTO Augusto BADURSI Andrea 4 nato a Policoro il 22O611 985 4 nato e Ferandina il19/02'1949 4 nato a Matera il18/021970 4 nalo e Pislicci il -

SEDI ASSEGNATE-Signed

Ministero dell’Istruzione UFFICIO SCOLASTICO REGIONALE PER LA BASILICATA Ufficio IV – Ambito territoriale di Matera Area I U.O. 2 – “Personale ATA” Resp. del procedimento: Aliotta Resp. dell’istruttoria: Vicenti Tel.: 0835 – 315243 -Tel.: 0835 – 315236 e-mail: [email protected] Procedura selettiva per l’internalizzazione dei servizi D.M. 1074/2019 e D.D. 2200/2019. SEDI SCELTE DAL PERSONALE CONVOCATO IL 27.2.2020 PER NOMINA A TEMPO INDETERMINATO PROFILO: COLLABORATORI SCOLASTICI N. POSTI SEDI ASSEGNATE NOMINATIVI MTIC82400V 1 MIGLIO LUCA I.C. MINOZZI – FESTA. MATERA MTIC82400V 2 GUGLIELMUCCI SALVATORE I.C. MINOZZI – FESTA. MATERA MTIC82400V 3 PIRRETTI ARGENZIA I.C. MINOZZI – FESTA. MATERA MTIC82400V 4 LOMONACO PALMA I.C. MINOZZI – FESTA. MATERA MTIC82500P 1 PAOLICELLI CHIARA ROSA I.C. TORRACA - MATERA MTIC82500P 2 // I.C. TORRACA- MATERA MTIC82700A 1 SANTERAMO MARIA I.C. PASCOLI - MATERA Via Lucana 194 – 75100 MATERA – Pec: [email protected] - E-mail: [email protected] Url: www.istruzionematera.it - Tel. 0835/3151 - C.F. e P.IVA: 80001420779 Ministero dell’Istruzione UFFICIO SCOLASTICO REGIONALE PER LA BASILICATA Ufficio IV – Ambito territoriale di Matera MTIC82700A 2 RONDINONE COSIMO DAMIANO I.C. PASCOLI - MATERA MTIC82700A 3 MARTINELLI LUCIA I.C. PASCOLI - MATERA MTIC82700A 4 MARTINELLI MICHELINA I.C. PASCOLI - MATERA MTIC828006 1 VENTURO CARMENIO I.C. FERMI - MATERA MTIC829002 1 CARLUCCI PATRIZIA I.C. N. 6 BRAMANTE - MATERA MTIC80900R 1 COLETTA MADDALENA I.C. IRSINA MTIC80900R 2 MANGIERI DONATA I.C. IRSINA MTIC80900R 3 MASCOLO MARIO I.C. IRSINA MTIC80900R 4 PACI VINCENZA I.C. IRSINA MTIC82100B 1 MIRAGLIA PANCRAZIO I.C. -

Una Boccata D'arte Press Release EN 08.2020

PRESS RELEASE Milan, 6 August 2020 Una boccata d’arte 20 artists 20 villages 20 regions 12.9 - 11.10.2020 A Fondazione Elpis project in collaboration with Galleria Continua Una boccata d’arte is a contemporary, widespread and unanimous art project, created by the Fondazione Elpis in collaboration with Galleria Continua. It is intended to be an injection of optimism, a spark of cultural, touristic and economic recovery based on the encounter between contemporary art and the historical and artistic beauty of twenty of the most beautiful and evocative villages in Italy. With Una boccata d’arte, the Fondazione Elpis also wishes to make a significant contribution to the support for contemporary art and the enhancement of Italian historical and landscape heritage, in light of the resumption of cultural activities in our country. In September, the twenty picturesque and characteristic chosen villages which enthusiastically joined the initiative will be enhanced by twenty site-specific contemporary art interventions carried out, for the most part, outdoors by emerging and established Italian artists invited by the Fondazione Elpis and Galleria Continua. Twenty artists for twenty villages, in all twenty regions of Italy. Over the past few weeks, the artists involved have conducted, in the company of representatives of the local municipalities, a first inspection in the selected village. In addition to a general visit of the village and a meeting with the inhabitants, the artists identified the site that will host their interventions, for which the conception and design phase is underway. For its first edition, Una boccata d’arte will inaugurate the artist’s works on the weekend of 12 and 13 September, at the same time in all the selected locations. -

Elenco Utilizzazione Ii Grado Mt

ASSEGNAZIONE DOCENTI - UTILIZZAZIONI PROVINCIALI Scuola Secondaria di II grado Anno scolastico di riferimento: 2020/21 USR BASILICATA - AT DI MATERA DATA DI PROVINCIA DI ORDINE SCUOLA DI PROVINCIA DI CLASSE DI CONCORSO/TIPO POSTO DI SCUOLA/AMBITO/PROVINCIA DI NOMINATIVO PRECEDENZA PUNTEGGIO TIPO POSTO RICHIESTO NOTE SEDE ASSEGNATA NASCITA NASCITA TITOLARITA' TITOLARITA' TITOLARITA' TITOLARITA' 9 H PENTASUGLIA+ MTIS016004- I.I.S BERNALDA- DE CARLO LUCREZIA 20/06/1972 BR SCUOLA SECONDARIA DI II GRADO MT A034-SCIENZE E TECNOLOGIE CHIMICHE 54,00 NORMALE CCNI art. 2, c. 1 LETT. b) 9 H LOPERFIDO FERRANDINA OLIVETTI VOLPE MARIA 06/01/1963 MT SCUOLA SECONDARIA DI II GRADO MT A045 - SCIENZE ECONOMICO-AZIENDALI MTIS0400T -CARLO LEVI 198,00 NORMALE CCNI art. 2, c. 1 LETT. b) IIS ISABELLA MORRA DI BELLO MARIA 25/08/1976 MT SCUOLA SECONDARIA DI II GRADO MT A011-DISCIPLINE LETTERARIE E LATINO MTIS002006- "FELICE ALDERISIO" CCNI 83,00 SOSTEGNO SOSTEGNO CCNI art. 2, c. 1 LETT. f RINUNCIA A012- Discipline letterarie negli istituti di istruzione MISEO MARIA CRISTINA 24/05/1970 MT SCUOLA SECONDARIA DI II GRADO MT MTIS00400T- CARLO LEVI 151,00 SOSTEGNO SOSTEGNO CCNI art. 2, c. 1 LETT. f IIS C.LEVI TRICARICO secondaria di II grado ISIS PITAGORA DEVINCENZIS IMMACOLATA 05/03/1959 MT SCUOLA SECONDARIA DI II GRADO MT AB24- LINGUA E CULTURA STRANIERA (INGLESE) MTIS002006- "FELICE ALDERISIO" 136,00 SOSTEGNO SOSTEGNO CCNI art. 2, c. 1 LETT. f MONTABANO "G.FORTUNATO" GATTO LOREDANA 20/12/1960 MT SCUOLA SECONDARIA DI II GRADO MT A031- SCIENZE DEGLI ALIMENTI MTIS011001- GIUSTINO FORTUNATO 128,00 SOSTEGNO SOSTEGNO CCNI art. -

Annata Venatoria 2020 / 2021 - Elenco Di Ammissione Dei Cacciatori Residenti E Domiciliati Nell'ambito: Atc A

ATC 2 POTENZA - ANNATA VENATORIA 2020 / 2021 - ELENCO DI AMMISSIONE DEI CACCIATORI RESIDENTI E DOMICILIATI NELL'AMBITO: ATC A Nro. provincia provincia provincia porto d'armi cognome nome data nascita comune nascita comune residenza comune domicilio porto d'armi questura attesa rilascio Ordine nascita residenza domicilio 18/06/2019 1 ATTANASIO PASQUALE 25/07/1953 NOCERA SUPERIORE SA POMARICO MT POMARICO MT 003377-p NOCERA INFERIORE 12/06/2019 2 BELMONTE FERDINANDO 06/04/1984 STIGLIANO MT ACCETTURA MT 173475-P MATERA 18/07/2014 3 BENEDETTO ANDREA 15/05/1990 PISTICCI MT BERNALDA MT BERNALDA MT 176130-O MATERA 24/06/2015 4 BRANDA PIETRO 01/02/1973 ACCETTURA MT ACCETTURA MT 52977-O MATERA 25/05/2018 5 BRANDA VINCENZO 23/07/1979 PISTOIA PT ACCETTURA MT 770494-O MATERA 11/01/2019 6 CALVELLO CATALDO 13/11/1949 IRSINA MT IRSINA MT IRSINA MT 173375-P MATERA 10/10/2017 7 CANDELA GIUSEPPE 26/10/1973 BARI BA IRSINA MT IRSINA MT 770335-O MATERA 01/08/2018 8 CAPPIELLO GIUSEPPE 05/06/1981 BARI BA IRSINA MT IRSINA MT 770566-O MATERA SAN GIORGIO A 20/07/2015 9 CASTALDO LUIGI 10/10/1943 NA POMARICO MT POMARICO MT 301851-0 MATERA CREMANO 12/05/2015 10 CAVALCANTE SALVATORE 30/04/1969 TRICARICO MT CALCIANO MT CALCIANO MT 529581-N MATERA 20/09/2019 11 CENTONZE GIUSEPPE 06/11/1965 BERNALDA MT BERNALDA MT BERNALDA MT 953099-O PISTICCI 24/08/2018 12 CERABONA GIULIANO 01/10/1985 TRICARICO MT CALCIANO MT CALCIANO MT 770624-O MATERA 01/09/2015 13 CORVAGLIA GIUSEPPE EMANUELE 18/08/1984 PISTICCI MT BERNALDA MT BERNALDA MT 615561-O MATERA DAMBROSIO 09/05/2016 14 GIUSEPPE -

Prima Categoria Gir. B

* COMITATO REGIONALE BASILICATA - STAGIONE SPORTIVA 2019/2020 - CAMPIONATO DI PRIMA CATEGORIA GIRONE B * .--------------------------------------------------------------. .--------------------------------------------------------------. .--------------------------------------------------------------. I ANDATA: 22/09/19 ! ! RITORNO: 12/01/20 I I ANDATA: 27/10/19 ! ! RITORNO: 16/02/20 I I ANDATA: 1/12/19 ! ! RITORNO: 22/03/20 I I ORE...: 15:30 ! 1 G I O R N A T A ! ORE....: 14:30 I I ORE...: 14:30 ! 6 G I O R N A T A ! ORE....: 15:00 I I ORE...: 14:30 ! 11 G I O R N A T A ! ORE....: 15:00 I I--------------------------------------------------------------I I--------------------------------------------------------------I I--------------------------------------------------------------I I CITTA DEI SASSI MATERA - CASTELSARACENO I I CASTELSARACENO - TRICARICO POZZO DI SICAR I I CASTELSARACENO - PEPPINO CAMPAGNA BERNALDA I I GRASSANO - LAINESE I I CITTA DEI SASSI MATERA - V.R. EPISCOPIA CALCIO I I LIBERTAS MONTESCAGLIOSO - GRASSANO I I POLISPORTIVA TRAMUTOLA - PEPPINO CAMPAGNA BERNALDA I I GRASSANO - SASSIMATERA I I REAL CHIAROMONTE - SASSIMATERA I I REAL CHIAROMONTE - V.R. EPISCOPIA CALCIO I I LAINESE - REAL CHIAROMONTE I I TRICARICO POZZO DI SICAR - CITTA DEI SASSI MATERA I I SALANDRA - LIBERTAS MONTESCAGLIOSO I I PEPPINO CAMPAGNA BERNALDA - VIGGIANELLO I I TURSI CALCIO 2008 - POLISPORTIVA TRAMUTOLA I I SASSIMATERA - TURSI CALCIO 2008 I I POLISPORTIVA TRAMUTOLA - SALANDRA I I V.R. EPISCOPIA CALCIO - LAINESE I I VIGGIANELLO - TRICARICO POZZO DI -

Determinazione Dei Collegi Elettorali Uninominali E Plurinominali Della Camera Dei Deputati E Del Senato Della Repubblica

Determinazione dei collegi elettorali uninominali e plurinominali della Camera dei deputati e del Senato della Repubblica Decreto legislativo 12 dicembre 2017, n. 189 BASILICATA Dicembre 2017 SERVIZIO STUDI TEL. 06 6706-2451 - [email protected] - @SR_Studi Dossier n. 567/2/Basilicata SERVIZIO STUDI Dipartimento Istituzioni Tel. 06 6760-9475 - [email protected] - @CD_istituzioni SERVIZIO STUDI Sezione Affari regionali Tel. 06 6760-9261 6760-3888 - [email protected] - @CD_istituzioni Atti del Governo n. 474/2/Basilicata La redazione del presente dossier è stata curata dal Servizio Studi della Camera dei deputati La documentazione dei Servizi e degli Uffici del Senato della Repubblica e della Camera dei deputati è destinata alle esigenze di documentazione interna per l'attività degli organi parlamentari e dei parlamentari. Si declina ogni responsabilità per la loro eventuale utilizzazione o riproduzione per fini non consentiti dalla legge. I contenuti originali possono essere riprodotti, nel rispetto della legge, a condizione che sia citata la fonte. File: ac0760b_basilicata.docx Basilicata Cartografie Camera dei deputati Per la circoscrizione Basilicata è presentata la seguente cartografia: ‐ Circoscrizione Basilicata, che mostra la ripartizione del territorio in due collegi uninominali Per l’elezione della Camera dei deputati il territorio della regione Basilicata costituisce un’unica circoscrizione, alla quale, in base alla popolazione rilevata dal censimento 2011, sono assegnati sei seggi, di cui due attribuiti in altrettanti collegi uninominali, per la cui conformazione non è stato possibile utilizzare pienamente il territorio dei collegi uninominali costituiti dal Decreto legislativo 10 dicembre 1993, n. 535 per l’elezione del Senato della Repubblica secondo la legge allora vigente (legge 4 agosto 1993, n.