Front Cover BLUE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DOCTOR WHO LOGOPOLIS Christopher H. Bidmead Based On

DOCTOR WHO LOGOPOLIS Christopher H. Bidmead Based on the BBC television serial by Christopher H. Bidmead by arrangement with the British Broadcasting Corporation 1. Events cast shadows before them, but the huger shadows creep over us unseen. When some great circumstance, hovering somewhere in the future, is a catastrophe of incalculable consequence, you may not see the signs in the small happenings that go before. The Doctor did, however - vaguely. While the Doctor paced back and forth in the TARDIS cloister room trying to make some sense of the tangle of troublesome thoughts that had followed him from Traken, in a completely different sector of the Universe, in a place called Earth, one such small foreshadowing was already beginning to unfold. It was a simple thing. A policeman leaned his bicycle against a police box, took a key from the breast pocket of his uniform jacket and unlocked the little telephone door to make a phone call. Police Constable Donald Seagrave was in a jovial mood. The sun was shining, the bicycle was performing perfectly since its overhaul last Saturday afternoon, and now that the water-main flooding in Burney Street was repaired he was on his way home for tea, if that was all right with the Super. It seemed to be a bad line. Seagrave could hear his Superintendent at the far end saying, 'Speak up . Who's that . .?', but there was this whirring noise, and then a sort of chuffing and groaning . The baffled constable looked into the telephone, and then banged it on his helmet to try to improve the connection. -

Doctor Who: Castrovalva

Still weak and confused after his fourth regeneration, the Doctor retreats to Castrovalva to recuperate. But Castrovalva is not the haven of peace and tranquility the Doctor and his companions are seeking. Far from being able to rest quietly, the unsuspecting time-travellers are caught up once again in the evil machinations of the Master. Only an act of supreme self-sacrifice will enable them to escape the maniacal lunacy of the renegade Time Lord. Among the many Doctor Who books available are the following recently published titles: Doctor Who and the Leisure Hive Doctor Who and the Visitation Doctor Who – Full Circle Doctor Who – Logopolis Doctor Who and the Sunmakers Doctor Who Crossword Book UK: £1 · 35 *Australia: $3 · 95 Malta: £M1 · 35c *Recommended Price TV tie-in ISBN 0 426 19326 1 This book is dedicated to M. C. Escher, whose drawings inspired it and provided its title. Thanks are also due to the Barbican Centre, London, England, where a working model of the disorienteering experiments provided valuable practical experience. DOCTOR WHO CASTROVALVA Based on the BBC television serial by Christopher H. Bidmead by arrangement with the British Broadcasting Corporation CHRISTOPHER H. BIDMEAD published by The Paperback Division of W. H. Allen & Co. Ltd A Target Book Published in 1983 by the Paperback Division of W.H. Allen & Co. Ltd A Howard & Wyndham Company 44 Hill Street, London W1X 8LB Novelisation copyright © Christopher H. Bidmead 1983 Original script copyright © Christopher H. Bidmead 1982 ‘Doctor Who’ series copyright © British Broadcasting Corporation 1982, 1983 Printed and bound in Great Britain by Hunt Barnard Printing Ltd, Aylesbury, Bucks ISBN 0 426 19326 1 This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. -

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS in SCIENCE FICTION and FANTASY (A Series Edited by Donald E

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS IN SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY (a series edited by Donald E. Palumbo and C.W. Sullivan III) 1 Worlds Apart? Dualism and Transgression in Contemporary Female Dystopias (Dunja M. Mohr, 2005) 2 Tolkien and Shakespeare: Essays on Shared Themes and Language (ed. Janet Brennan Croft, 2007) 3 Culture, Identities and Technology in the Star Wars Films: Essays on the Two Trilogies (ed. Carl Silvio, Tony M. Vinci, 2007) 4 The Influence of Star Trek on Television, Film and Culture (ed. Lincoln Geraghty, 2008) 5 Hugo Gernsback and the Century of Science Fiction (Gary Westfahl, 2007) 6 One Earth, One People: The Mythopoeic Fantasy Series of Ursula K. Le Guin, Lloyd Alexander, Madeleine L’Engle and Orson Scott Card (Marek Oziewicz, 2008) 7 The Evolution of Tolkien’s Mythology: A Study of the History of Middle-earth (Elizabeth A. Whittingham, 2008) 8 H. Beam Piper: A Biography (John F. Carr, 2008) 9 Dreams and Nightmares: Science and Technology in Myth and Fiction (Mordecai Roshwald, 2008) 10 Lilith in a New Light: Essays on the George MacDonald Fantasy Novel (ed. Lucas H. Harriman, 2008) 11 Feminist Narrative and the Supernatural: The Function of Fantastic Devices in Seven Recent Novels (Katherine J. Weese, 2008) 12 The Science of Fiction and the Fiction of Science: Collected Essays on SF Storytelling and the Gnostic Imagination (Frank McConnell, ed. Gary Westfahl, 2009) 13 Kim Stanley Robinson Maps the Unimaginable: Critical Essays (ed. William J. Burling, 2009) 14 The Inter-Galactic Playground: A Critical Study of Children’s and Teens’ Science Fiction (Farah Mendlesohn, 2009) 15 Science Fiction from Québec: A Postcolonial Study (Amy J. -

MT337 201102 Earthshock

EARTHSHOCK By Eric Saward Mysterious Theatre 337 – Show 201102 Revision 3 By the usual suspects Transcription by Robert Warnock (1,2) and Steven W Hill (3,4) Theme starts Didn’t we just do this one? Stars More stars Bright stars Peter! Hey it’s that guy from the Gallifrey convention video. Peter zooms towards camera I saw a guy who looks just like him in the hotel. More bright stars Neon logo Neon logo zooms out Earthshock I love one-word titles. By Eric Saward Part One Star One. Long shot of the BBC Quarry. © Some people in coveralls rappel up the side of a hill. If that’s tug of war, you’re doing it wrong. I love the BBC quarry. Lieutenant Scott reaches out to help Professor Kyle Another boring planet in the middle of nowhere. over the top. She gasps. They run away from the camera towards another hill Is this Halo? where some other troopers are standing guard. They run past an oval-shaped, blue tent to where some other troopers are standing, and stop. Scott looks around a bit, the moves forward again. He heads towards a “tunnel” entrance where some more troopers are standing. Kyle and Snyder are looking into the entrance as Scott walks up. Look, she’s got headlights. Phwooar! Page 1 SNYDER Nothing. Kyle turns around and walks away from the tunnel Quarry. entrance very slowly. PROF KYLE How does this thing work? It’s called a microfiche. WALTERS It focuses upon the electrical activity of the body-heartbeat, things like that. -

A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM of DOCTOR WHO Noah Zepponi University of the Pacific, [email protected]

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2018 THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO Noah Zepponi University of the Pacific, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Zepponi, Noah. (2018). THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO. University of the Pacific, Thesis. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds/2988 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2 THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO by Noah B. Zepponi A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS College of the Pacific Communication University of the Pacific Stockton, California 2018 3 THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO by Noah B. Zepponi APPROVED BY: Thesis Advisor: Marlin Bates, Ph.D. Committee Member: Teresa Bergman, Ph.D. Committee Member: Paul Turpin, Ph.D. Department Chair: Paul Turpin, Ph.D. Dean of Graduate School: Thomas Naehr, Ph.D. 4 DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my father, Michael Zepponi. 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is here that I would like to give thanks to the people which helped me along the way to completing my thesis. First and foremost, Dr. -

Dr Who Pdf.Pdf

DOCTOR WHO - it's a question and a statement... Compiled by James Deacon [2013] http://aetw.org/omega.html DOCTOR WHO - it's a Question, and a Statement ... Every now and then, I read comments from Whovians about how the programme is called: "Doctor Who" - and how you shouldn't write the title as: "Dr. Who". Also, how the central character is called: "The Doctor", and should not be referred to as: "Doctor Who" (or "Dr. Who" for that matter) But of course, the Truth never quite that simple As the Evidence below will show... * * * * * * * http://aetw.org/omega.html THE PROGRAMME Yes, the programme is titled: "Doctor Who", but from the very beginning – in fact from before the beginning, the title has also been written as: “DR WHO”. From the BBC Archive Original 'treatment' (Proposal notes) for the 1963 series: Source: http://www.bbc.co.uk/archive/doctorwho/6403.shtml?page=1 http://aetw.org/omega.html And as to the central character ... Just as with the programme itself - from before the beginning, the central character has also been referred to as: "DR. WHO". [From the same original proposal document:] http://aetw.org/omega.html In the BBC's own 'Radio Times' TV guide (issue dated 14 November 1963), both the programme and the central character are called: "Dr. Who" On page 7 of the BBC 'Radio Times' TV guide (issue dated 21 November 1963) there is a short feature on the new programme: Again, the programme is titled: "DR. WHO" "In this series of adventures in space and time the title-role [i.e. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Accessing■i the World's UMI Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 882462 James Wright’s poetry of intimacy Terman, Philip S., Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1988 Copyright ©1988 by Terman, Philip S. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, M I 48106 JAMES WRIGHT'S POETRY OF INTIMACY DISSERTATION Presented In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Philip S. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Doctor Who Vampire Science by Jonathan Blum 3 Jonathan Blum Quotes on Doctor Who: Vampire Science - Quotes.Pub

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Doctor Who Vampire Science by Jonathan Blum 3 Jonathan Blum Quotes on Doctor Who: Vampire Science - Quotes.pub. Here you will find all the famous Jonathan Blum quotes. There are more than 3+ quotes in our Jonathan Blum quotes collection. We have collected all of them and made stunning Jonathan Blum wallpapers & posters out of those quotes. You can use this wallpapers & posters on mobile, desktop, print and frame them or share them on the various social media platforms. You can download the quotes images in various different sizes for free. In the below list you can find quotes in various categories like Doctor Who: Vampire Science. Jacob Licklider: Reviews. Having six months pass since reviewing The Eight Doctors has given me quite a bit of perspective on the issue of writing for the Eighth Doctor. The Eighth Doctor is perhaps the Doctor with the largest blank slate when it comes to character development. His line of novels began publishing in June 1997, one year after the airing of The TV Movie , and the Time War as an effect on the character would only come when the series was revived in 2005. All we get is that he’s a hopeless romantic who gets amnesia when he regenerates and during The Eight Doctors picks up companion Samantha Jones for a series of travels. Terrance Dicks focused on a celebration of continuity for his novel, but this leaves Eight and Sam as a blank slate. We know that Sam Jones is a vegetarian and liberal activist living near enough to Coal Hill School while having an overactive sense of justice. -

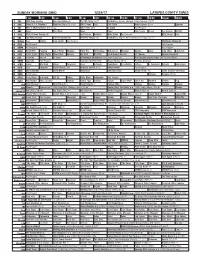

Sunday Morning Grid 12/24/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/24/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Los Angeles Chargers at New York Jets. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid PGA TOUR Action Sports (N) Å Spartan 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Los Angeles Rams at Tennessee Titans. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program Christmas Miracle at 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Milk Street Mexican Martha Jazzy Julia Child Chefs Life 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ 53rd Annual Wassail St. Thomas Holiday Handbells 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch A Firehouse Christmas (2016) Anna Hutchison. The Spruces and the Pines (2017) Jonna Walsh. 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Grandma Got Run Over Netas Divinas (TV14) Premios Juventud 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

Doctor Who: the Doctor, Tegan, Nyssa and Adric

WWW.BIGFINISH.COM • NEW AUDIO ADVENTURES DOCTOR WHO: THE CLASS OF 82 THE DOCTOR, TEGAN, NYSSA AND ADRIC REUNITE FOR BIG FINISH! PLUS! DOCTOR WHO: PHILIP OLIVIER ON HEX AND HECTOR! THE FIFTH DOCTOR BOX SET: WRITING FOR ADRIC! AND IT’S ALL CHANGE FOR BLAKE’S 7… ISSUE 66 • AUGUST 2014 WELCOME TO BIG FINISH! We love stories and we make great full-cast audio drama and audiobooks you can buy on CD and/or download Big Finish… Subscribers get more We love stories. at bigfinish.com! Our audio productions are based on much- If you subscribe, depending on the range you loved TV series like Doctor Who, Dark subscribe to, you get free audiobooks, PDFs Shadows, Blake’s 7, Stargate and Highlander of scripts, extra behind-the-scenes material, a as well as classic characters such as Sherlock bonus release and discounts. Holmes, The Phantom of the Opera and Dorian Gray, plus original creations such as Graceless and The Adventures of Bernice Summerfield. www.bigfinish.com We publish a growing number of books (non- You can access a video guide to the site by fiction, novels and short stories) from new and clicking here. established authors. WWW.BIGFINISH.COM @BIGFINISH /THEBIGFINISH VORTEX MAGAZINE PAGE 3 Sneak Previews & Whispers Editorial OMETIMES, the little things that you do go a lot further than you would ever expect. At Big Finish, S Paul Spragg was testament to that. Since Paul’s tragic passing earlier this year, Big Finish has been inundated with messages from people whose lives Paul touched, to many different extents, from friends who knew him well, to those he helped with day-to-day customer service enquiries. -

The Collected Poems of Giorgio De Chirico

195 THE COLLECTED POEMS OF GIORGIO DE CHIRICO I Paris 1911-1915 1. Hopes1 Te astronomer poets are exuberant. Te day is radiant the public square flled with sunlight. Tey are leaning against the veranda. Music and love. Te incredibly beautiful woman. I would sacrifce my life for her velvet eyes. A painter has painted a huge red smokestack Tat a poet adores like a divinity. I remember that night of springtime and cadavers. Te river was carrying gravestones that have disappeared. Who still wants to live? Promises are more beautiful. So many fags are fying from the railroad station. Provided the clock does not stop A government minister is supposed to arrive. He is intelligent and mild he is smiling. He comprehends everything and at night by the glow of a smoking lamp While the warrior of stone dozes on the dark public square He writes sad passionate love letters. 1 Original title, Espoirs, published in “La révolution surréaliste”, n. 5, Paris 15 October 1925, p. 6. Te Éluard-Picasso Manuscripts (1911-1915), including theoretical writings and poems written in French and 29 drawings, constitute an essential testimony of de Chirico’s early theoretical and artistic considerations. (See J. de Sanna, Giorgio de Chirico - Disegno, Electa, Milan 2004, pp. 12-15). De Chirico arrived in Paris, from Florence, on 14 July 1911 and remained in the capital until late May 1915 when, called to arms, he returned to Italy with his brother Alberto Savinio. Initially in Paul Éluard’s collection, the manuscripts were later acquired by Picasso. Today they are conserved in ‘Fonds Picasso’ at Musée National Picasso, Paris. -

Doctor Who and the Politics of Casting Lorna Jowett, University

Doctor Who and the politics of casting Lorna Jowett, University of Northampton Abstract: This article argues that while long-running science fiction series Doctor Who (1963-89; 1996; 2005-) has started to address a lack of diversity in its casting, there are still significant imbalances. Characters appearing in single episodes are more likely to be colourblind cast than recurring and major characters, particularly the title character. This is problematic for the BBC as a public service broadcaster but is also indicative of larger inequalities in the television industry. Examining various examples of actors cast in Doctor Who, including Pearl Mackie who plays companion Bill Potts, the article argues that while steady progress is being made – in the series and in the industry – colourblind casting often comes into tension with commercial interests and more risk-averse decision-making. Keywords: colourblind casting, television industry, actors, inequality, diversity, race, LGBTQ+ 1 Doctor Who and the politics of casting Lorna Jowett The Britain I come from is the most successful, diverse, multicultural country on earth. But here’s my point: you wouldn’t know it if you turned on the TV. Too many of our creative decision-makers share the same background. They decide which stories get told, and those stories decide how Britain is viewed. (Idris Elba 2016) If anyone watches Bill and she makes them feel that there is more of a place for them then that’s fantastic. I remember not seeing people that looked like me on TV when I was little. My mum would shout: ‘Pearl! Come and see.