Eclosure of the Cybermen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS in SCIENCE FICTION and FANTASY (A Series Edited by Donald E

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS IN SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY (a series edited by Donald E. Palumbo and C.W. Sullivan III) 1 Worlds Apart? Dualism and Transgression in Contemporary Female Dystopias (Dunja M. Mohr, 2005) 2 Tolkien and Shakespeare: Essays on Shared Themes and Language (ed. Janet Brennan Croft, 2007) 3 Culture, Identities and Technology in the Star Wars Films: Essays on the Two Trilogies (ed. Carl Silvio, Tony M. Vinci, 2007) 4 The Influence of Star Trek on Television, Film and Culture (ed. Lincoln Geraghty, 2008) 5 Hugo Gernsback and the Century of Science Fiction (Gary Westfahl, 2007) 6 One Earth, One People: The Mythopoeic Fantasy Series of Ursula K. Le Guin, Lloyd Alexander, Madeleine L’Engle and Orson Scott Card (Marek Oziewicz, 2008) 7 The Evolution of Tolkien’s Mythology: A Study of the History of Middle-earth (Elizabeth A. Whittingham, 2008) 8 H. Beam Piper: A Biography (John F. Carr, 2008) 9 Dreams and Nightmares: Science and Technology in Myth and Fiction (Mordecai Roshwald, 2008) 10 Lilith in a New Light: Essays on the George MacDonald Fantasy Novel (ed. Lucas H. Harriman, 2008) 11 Feminist Narrative and the Supernatural: The Function of Fantastic Devices in Seven Recent Novels (Katherine J. Weese, 2008) 12 The Science of Fiction and the Fiction of Science: Collected Essays on SF Storytelling and the Gnostic Imagination (Frank McConnell, ed. Gary Westfahl, 2009) 13 Kim Stanley Robinson Maps the Unimaginable: Critical Essays (ed. William J. Burling, 2009) 14 The Inter-Galactic Playground: A Critical Study of Children’s and Teens’ Science Fiction (Farah Mendlesohn, 2009) 15 Science Fiction from Québec: A Postcolonial Study (Amy J. -

Doctor Who 4 Ep 17.GREENS

Doctor Who 4 Episode 17 By Russell T Davies Shooting Script GREENS 18th April 2009 Prep starts: 23rd Feb Shooting starts: 30th March Tale Writer's The Doctor Who 4 Episode 17 SHOOTING SCRIPT 20/03/09 page 1 1 FX SHOT - PLANET EARTH 1 FX: THE EARTH, suspended in space, in all its beauty. Over this, the NARRATOR. An old, wise man. NARRATOR It is said that in the final days of Planet Earth, everyone had bad dreams. MIX TO: 2 EXT. SHOPPING STREET - NIGHT 1 2 CAMERA craning down a huge, outdoor CHRISTMAS TREE... NARRATOR To the west of the north of that world, the Human Race did gather, in celebration of a pagan rite, to banish the cold and the dark. ...craning down to find a SALVATION ARMY BRASS BAND. God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen; the most mournful of carols. Moving round to find a few ONLOOKERS Tale(SHOPPERS in b/g). People, just dotted about, pausing. A woman & gran. Three teenagers. A family, mum, dad and little daughter... NARRATOR (CONT'D) Each and every one of those people had dreamt of the terrible things to come. But they forgot, because they must; they forgot their nightmares, of fire and war and insanity. Writer's They forgot... ...then finding WILFRED MOTT. NARRATOR (CONT'D) TheExcept for one. Wilf's troubled, uneasy, and on his CLOSE UP - INTERCUT, fast, violent - CU of a FACE, bleached, against black - manic laughter - a familiar face, it's - Wilf blinks. Shakes it off. Turns away... CUT TO WIDER. Wilf wandering along. Lost in thought. -

MT337 201102 Earthshock

EARTHSHOCK By Eric Saward Mysterious Theatre 337 – Show 201102 Revision 3 By the usual suspects Transcription by Robert Warnock (1,2) and Steven W Hill (3,4) Theme starts Didn’t we just do this one? Stars More stars Bright stars Peter! Hey it’s that guy from the Gallifrey convention video. Peter zooms towards camera I saw a guy who looks just like him in the hotel. More bright stars Neon logo Neon logo zooms out Earthshock I love one-word titles. By Eric Saward Part One Star One. Long shot of the BBC Quarry. © Some people in coveralls rappel up the side of a hill. If that’s tug of war, you’re doing it wrong. I love the BBC quarry. Lieutenant Scott reaches out to help Professor Kyle Another boring planet in the middle of nowhere. over the top. She gasps. They run away from the camera towards another hill Is this Halo? where some other troopers are standing guard. They run past an oval-shaped, blue tent to where some other troopers are standing, and stop. Scott looks around a bit, the moves forward again. He heads towards a “tunnel” entrance where some more troopers are standing. Kyle and Snyder are looking into the entrance as Scott walks up. Look, she’s got headlights. Phwooar! Page 1 SNYDER Nothing. Kyle turns around and walks away from the tunnel Quarry. entrance very slowly. PROF KYLE How does this thing work? It’s called a microfiche. WALTERS It focuses upon the electrical activity of the body-heartbeat, things like that. -

A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM of DOCTOR WHO Noah Zepponi University of the Pacific, [email protected]

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2018 THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO Noah Zepponi University of the Pacific, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Zepponi, Noah. (2018). THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO. University of the Pacific, Thesis. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds/2988 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 2 THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO by Noah B. Zepponi A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS College of the Pacific Communication University of the Pacific Stockton, California 2018 3 THE DOCTOR OF CHANGE: A IDEOLOGICAL CRITICISM OF DOCTOR WHO by Noah B. Zepponi APPROVED BY: Thesis Advisor: Marlin Bates, Ph.D. Committee Member: Teresa Bergman, Ph.D. Committee Member: Paul Turpin, Ph.D. Department Chair: Paul Turpin, Ph.D. Dean of Graduate School: Thomas Naehr, Ph.D. 4 DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my father, Michael Zepponi. 5 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It is here that I would like to give thanks to the people which helped me along the way to completing my thesis. First and foremost, Dr. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Accessing■i the World's UMI Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 882462 James Wright’s poetry of intimacy Terman, Philip S., Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1988 Copyright ©1988 by Terman, Philip S. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, M I 48106 JAMES WRIGHT'S POETRY OF INTIMACY DISSERTATION Presented In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Philip S. -

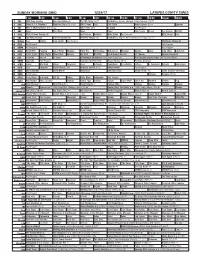

Sunday Morning Grid 12/24/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/24/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Los Angeles Chargers at New York Jets. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid PGA TOUR Action Sports (N) Å Spartan 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Los Angeles Rams at Tennessee Titans. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program Christmas Miracle at 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Milk Street Mexican Martha Jazzy Julia Child Chefs Life 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ 53rd Annual Wassail St. Thomas Holiday Handbells 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch A Firehouse Christmas (2016) Anna Hutchison. The Spruces and the Pines (2017) Jonna Walsh. 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Grandma Got Run Over Netas Divinas (TV14) Premios Juventud 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

The Collected Poems of Giorgio De Chirico

195 THE COLLECTED POEMS OF GIORGIO DE CHIRICO I Paris 1911-1915 1. Hopes1 Te astronomer poets are exuberant. Te day is radiant the public square flled with sunlight. Tey are leaning against the veranda. Music and love. Te incredibly beautiful woman. I would sacrifce my life for her velvet eyes. A painter has painted a huge red smokestack Tat a poet adores like a divinity. I remember that night of springtime and cadavers. Te river was carrying gravestones that have disappeared. Who still wants to live? Promises are more beautiful. So many fags are fying from the railroad station. Provided the clock does not stop A government minister is supposed to arrive. He is intelligent and mild he is smiling. He comprehends everything and at night by the glow of a smoking lamp While the warrior of stone dozes on the dark public square He writes sad passionate love letters. 1 Original title, Espoirs, published in “La révolution surréaliste”, n. 5, Paris 15 October 1925, p. 6. Te Éluard-Picasso Manuscripts (1911-1915), including theoretical writings and poems written in French and 29 drawings, constitute an essential testimony of de Chirico’s early theoretical and artistic considerations. (See J. de Sanna, Giorgio de Chirico - Disegno, Electa, Milan 2004, pp. 12-15). De Chirico arrived in Paris, from Florence, on 14 July 1911 and remained in the capital until late May 1915 when, called to arms, he returned to Italy with his brother Alberto Savinio. Initially in Paul Éluard’s collection, the manuscripts were later acquired by Picasso. Today they are conserved in ‘Fonds Picasso’ at Musée National Picasso, Paris. -

Doctor Who and the Politics of Casting Lorna Jowett, University

Doctor Who and the politics of casting Lorna Jowett, University of Northampton Abstract: This article argues that while long-running science fiction series Doctor Who (1963-89; 1996; 2005-) has started to address a lack of diversity in its casting, there are still significant imbalances. Characters appearing in single episodes are more likely to be colourblind cast than recurring and major characters, particularly the title character. This is problematic for the BBC as a public service broadcaster but is also indicative of larger inequalities in the television industry. Examining various examples of actors cast in Doctor Who, including Pearl Mackie who plays companion Bill Potts, the article argues that while steady progress is being made – in the series and in the industry – colourblind casting often comes into tension with commercial interests and more risk-averse decision-making. Keywords: colourblind casting, television industry, actors, inequality, diversity, race, LGBTQ+ 1 Doctor Who and the politics of casting Lorna Jowett The Britain I come from is the most successful, diverse, multicultural country on earth. But here’s my point: you wouldn’t know it if you turned on the TV. Too many of our creative decision-makers share the same background. They decide which stories get told, and those stories decide how Britain is viewed. (Idris Elba 2016) If anyone watches Bill and she makes them feel that there is more of a place for them then that’s fantastic. I remember not seeing people that looked like me on TV when I was little. My mum would shout: ‘Pearl! Come and see. -

Full Circle Sampler

The Black Archive #15 FULL CIRCLE SAMPLER By John Toon Second edition published February 2018 by Obverse Books Cover Design © Cody Schell Text © John Toon, 2018 Range Editors: James Cooray Smith, Philip Purser-Hallard John would like to thank: Phil and Jim for all of their encouragement, suggestions and feedback; Andrew Smith for kindly giving up his time to discuss some of the points raised in this book; Matthew Kilburn for using his access to the Bodleian Library to help me with my citations; Alex Pinfold for pointing out the Blake’s 7 episode I’d overlooked; Jo Toon and Darusha Wehm for beta reading my first draft; and Jo again for giving me the support and time to work on this book. John Toon has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding, cover or e-book other than which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publisher. 2 For you. Yes, you! Go on, you deserve it. 3 Also Available The Black Archive #1: Rose by Jon Arnold The Black Archive #2: The Massacre by James Cooray Smith The Black Archive #3: The Ambassadors of Death by LM Myles The Black Archive #4: Dark Water / Death in Heaven by Philip Purser-Hallard The Black Archive #5: Image of the Fendahl -

Doctor Who's Back

The Wall of Lies Number 167 Newsletter established 1991, club formed June first 1980 The newsletter of the South Australian Doctor Who Fan Club Inc., also known as SFSA Final STATE Adelaide, July–August 2017 WEAThEr: Azimuth Solstice Free Doctor Who’s back ... by staff writers ... but ... not for another six months. Peter Capaldi finished work on the untitled 2017 Doctor Who Christmas special on July 11, 2017. He brought cake to the fans waiting outside the Cardiff studios and had other cast members to accompany him. At age 15 he wrote to the Doctor Who production office, demanding to replace the president of the fan club. Aged 18, he burned his collection as a rite of passage. O u While he may seem to be the nicest Doctor S t So ever, he has turned villainous before. on Peter Capaldi demonstrates the proper way n! Consequently, we recommend you don’t eat to wear a Walkman while showering (The Comic Strip Presents: Jealousy). his cake, you don’t know what he’s put in it. The First Doctor for Christmas! by staff writers The end for the Twelfth Doctor returns to the origins of the show. The end of series ten has left audiences with a cliffhanger, to be resolved in the 2017 Christmas SFSA magazine # 33 special. The BBC has shared their interpretation of the final scenes in The Doctor Falls. O u N t * The glowing light does represent his regeneration, No ow which he is suppressing. ! * The Christmas special will see the regeneration complete with a new incarnation of the character . -

Doctor Who: Silver Nemesis

Launched into space 350 years ago, a meteor is returning to Earth – and inside it waits Nemesis, a silver statue made of the living metal validium, the most dangerous substance in the Universe. Evil powers await the statue's return: the neo-Nazi de Flores and his stormtroopers; Lady Peinforte, who saw Nemesis exiled in 1638 and has propelled herself forward in time; and the advance party of a Cyberman invasion force. And in the garden of a Windsor pub, the Doctor and Ace are enjoying the timeless sounds of a jazz quartet . This story celebrates 25 years of Doctor Who on television. Distributed by USA: LYLE STUART INC, 120 Enterprise Ave, Secaucus, New Jersey 07094 USA CANADA: CANCOAST BOOKS LTD, Unit 3, 90 Signet Drive, Weston, Ontario M9L 1T5 Canada AUSTRALIA: HODDER & STOUGHTON (AUS) PTY LTD, Rydalmere Business Park, 10-16 South Street, Rydalmere, N.S.W. 2116 Australia NEW ZEALAND: MACDONALD PUBLISHERS (NZ) LTD, 42/44 View Road, Glenfield, AUCKLAND 10, New Zealand ISBN 0- 426-20340-2 UK: £1.99 *USA: $3.95 ,-7IA4C6-cadeah— CANADA: $4.95 NZ: $8.99 *AUSTRALIA: $5.95 *RECOMMENDED PRICE Science Fiction/TV Tie-in DOCTOR WHO SILVER NEMESIS Based on the BBC television programme by Kevin Clarke by arrangement with BBC Books, a division of BBC Enterprises Ltd Kevin Clarke Number 143 in the Target Doctor Who Library published by The Paperback Division of W. H. Allen & Co. Plc A Target Book Published in 1989 By the Paperback Division of W. H. Allen & Co. Plc Sekforde House, 175/9 St John Street, London EC1V 4LL Novelization copyright © Kevin Clarke -

Doctor Who 1 Doctor Who

Doctor Who 1 Doctor Who This article is about the television series. For other uses, see Doctor Who (disambiguation). Doctor Who Genre Science fiction drama Created by • Sydney Newman • C. E. Webber • Donald Wilson Written by Various Directed by Various Starring Various Doctors (as of 2014, Peter Capaldi) Various companions (as of 2014, Jenna Coleman) Theme music composer • Ron Grainer • Delia Derbyshire Opening theme Doctor Who theme music Composer(s) Various composers (as of 2005, Murray Gold) Country of origin United Kingdom No. of seasons 26 (1963–89) plus one TV film (1996) No. of series 7 (2005–present) No. of episodes 800 (97 missing) (List of episodes) Production Executive producer(s) Various (as of 2014, Steven Moffat and Brian Minchin) Camera setup Single/multiple-camera hybrid Running time Regular episodes: • 25 minutes (1963–84, 1986–89) • 45 minutes (1985, 2005–present) Specials: Various: 50–75 minutes Broadcast Original channel BBC One (1963–1989, 1996, 2005–present) BBC One HD (2010–present) BBC HD (2007–10) Picture format • 405-line Black-and-white (1963–67) • 625-line Black-and-white (1968–69) • 625-line PAL (1970–89) • 525-line NTSC (1996) • 576i 16:9 DTV (2005–08) • 1080i HDTV (2009–present) Doctor Who 2 Audio format Monaural (1963–87) Stereo (1988–89; 1996; 2005–08) 5.1 Surround Sound (2009–present) Original run Classic series: 23 November 1963 – 6 December 1989 Television film: 12 May 1996 Revived series: 26 March 2005 – present Chronology Related shows • K-9 and Company (1981) • Torchwood (2006–11) • The Sarah Jane Adventures (2007–11) • K-9 (2009–10) • Doctor Who Confidential (2005–11) • Totally Doctor Who (2006–07) External links [1] Doctor Who at the BBC Doctor Who is a British science-fiction television programme produced by the BBC.