Dark Water / Death in Heaven

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VORTEX Playing Mrs Constance Clarke

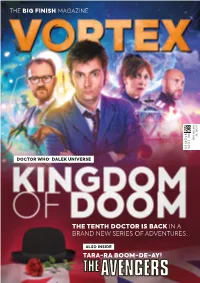

THE BIG FINISH MAGAZINE MARCH 2021 MARCH ISSUE 145 DOCTOR WHO: DALEK UNIVERSE THE TENTH DOCTOR IS BACK IN A BRAND NEW SERIES OF ADVENTURES… ALSO INSIDE TARA-RA BOOM-DE-AY! WWW.BIGFINISH.COM @BIGFINISH THEBIGFINISH @BIGFINISHPROD BIGFINISHPROD BIG-FINISH WE MAKE GREAT FULL-CAST AUDIO DRAMAS AND AUDIOBOOKS THAT ARE AVAILABLE TO BUY ON CD AND/OR DOWNLOAD WE LOVE STORIES Our audio productions are based on much-loved TV series like Doctor Who, Torchwood, Dark Shadows, Blake’s 7, The Avengers, The Prisoner, The Omega Factor, Terrahawks, Captain Scarlet, Space: 1999 and Survivors, as well as classics such as HG Wells, Shakespeare, Sherlock Holmes, The Phantom of the Opera and Dorian Gray. We also produce original creations such as Graceless, Charlotte Pollard and The Adventures of Bernice Summerfield, plus the THE BIG FINISH APP Big Finish Originals range featuring seven great new series: The majority of Big Finish releases ATA Girl, Cicero, Jeremiah Bourne in Time, Shilling & Sixpence can be accessed on-the-go via Investigate, Blind Terror, Transference and The Human Frontier. the Big Finish App, available for both Apple and Android devices. Secure online ordering and details of all our products can be found at: bgfn.sh/aboutBF EDITORIAL SINCE DOCTOR Who returned to our screens we’ve met many new companions, joining the rollercoaster ride that is life in the TARDIS. We all have our favourites but THE SIXTH DOCTOR ADVENTURES I’ve always been a huge fan of Rory Williams. He’s the most down-to-earth person we’ve met – a nurse in his day job – who gets dragged into the Doctor’s world THE ELEVEN through his relationship with Amelia Pond. -

{TEXTBOOK} the Anachronauts Pdf Free Download

THE ANACHRONAUTS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Simon Guerrier | none | 31 Jan 2012 | Big Finish Productions Ltd | 9781844356119 | English | Maidenhead, United Kingdom The Anachronauts PDF Book Marvel Comics. Raston feared that Merlin would see him as an unworthy successor to the role of Black Knight, and would take the Ebony Blade from him, yet when he met the present day Black Knight, he dismissed Sir Percy as "a fop and a fool. Sister to Archmagus Lillith. Though they gave Stark a good run for his money, they weren't able to defeat the super-hero. Deathunt is a cyborg brought from his time period by Kang to protect Chronopolis. And why doesn't the Doctor want to escape? Una : Los Muertos. Steven tells her she's imagining it. You know the saying: There's no time like the present Kang pulled Wildrun from his time period to serve as one of his elite guards in Chronopolis. Despite being from much further in the past than other Anachronauts 12, years ago , he showed no signs of having trouble adapting to life in the future. Sara falls asleep and wakes feeling better than ever, her broken arm healed. She-Thing was revealed to be a Skrull imposter. Accursed lodestones! Josh rated it really liked it Dec 20, The Doctor calls this figure a "Time Sprite" but says it's a myth, a fairy tale, something that does not exist. Stream the best stories. They are interrogated there and for the first time Steven understands that nothing of that is happening Tony Stark was the arrogant son of wealthy, weapon manufacturer Howard Stark. -

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS in SCIENCE FICTION and FANTASY (A Series Edited by Donald E

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS IN SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY (a series edited by Donald E. Palumbo and C.W. Sullivan III) 1 Worlds Apart? Dualism and Transgression in Contemporary Female Dystopias (Dunja M. Mohr, 2005) 2 Tolkien and Shakespeare: Essays on Shared Themes and Language (ed. Janet Brennan Croft, 2007) 3 Culture, Identities and Technology in the Star Wars Films: Essays on the Two Trilogies (ed. Carl Silvio, Tony M. Vinci, 2007) 4 The Influence of Star Trek on Television, Film and Culture (ed. Lincoln Geraghty, 2008) 5 Hugo Gernsback and the Century of Science Fiction (Gary Westfahl, 2007) 6 One Earth, One People: The Mythopoeic Fantasy Series of Ursula K. Le Guin, Lloyd Alexander, Madeleine L’Engle and Orson Scott Card (Marek Oziewicz, 2008) 7 The Evolution of Tolkien’s Mythology: A Study of the History of Middle-earth (Elizabeth A. Whittingham, 2008) 8 H. Beam Piper: A Biography (John F. Carr, 2008) 9 Dreams and Nightmares: Science and Technology in Myth and Fiction (Mordecai Roshwald, 2008) 10 Lilith in a New Light: Essays on the George MacDonald Fantasy Novel (ed. Lucas H. Harriman, 2008) 11 Feminist Narrative and the Supernatural: The Function of Fantastic Devices in Seven Recent Novels (Katherine J. Weese, 2008) 12 The Science of Fiction and the Fiction of Science: Collected Essays on SF Storytelling and the Gnostic Imagination (Frank McConnell, ed. Gary Westfahl, 2009) 13 Kim Stanley Robinson Maps the Unimaginable: Critical Essays (ed. William J. Burling, 2009) 14 The Inter-Galactic Playground: A Critical Study of Children’s and Teens’ Science Fiction (Farah Mendlesohn, 2009) 15 Science Fiction from Québec: A Postcolonial Study (Amy J. -

1 2019 Gally Academic Track Friday, February 15

2019 Gally Academic Track Friday, February 15, 2019 3:00-3:15 KEYNOTE “The Fandom Hierarchy: Women of Color’s Fight For Visibility In Fandom Spaces” Tai Gooden Women of Color (WoC) have been fervent Doctor Who fans for several decades. However, the fandom often reflects societal hierarchies upheld by White privilege that result in ignoring and diminishing WoC’s opinions, contributions, and legitimate concerns about issues in terms of representation. Additionally, WoC and non-binary (NB) people of color’s voices are not centered as often in journalism, podcasting, and media formats nor convention panels as much as their White counterparts. This noticeable disparity has led to many WoC, even those who are deemed “important” in fandom spaces, to encounter racism, sexism, and, depending on the individual, homophobia and transphobia in a place that is supposed to have open availability to everyone. I can attest to this experience as someone who has a somewhat heightened level of visibility in fandom as a pop culture/entertainment writer who extensively covers Doctor Who. This presentation will examine women of color in the Doctor Who fandom in terms of their interactions with non-POC fans and difficulties obtaining opportunities in media, online, and at conventions. The show’s representation of fandom and the necessity for equity versus equality will also be discussed to craft a better understanding of how to tackle this pervasive issue. Other actionable solutions to encourage intersectionality in the fandom will be discussed including privileged people listening to WoC and non- binary people’s concerns/suggestions, respectfully interacting with them online and in person, recognizing and utilizing their privilege to encourage more inclusivity, standing in solidarity with them on critical issues, and lending their support to WoC creatives. -

Dundee Comics Day 2011

PRESS RELEASE FROM THE UNIVERSITY OF DUNDEE ‘WOT COMICS TAUGHT ME…’ – DUNDEE COMICS DAY 2011 Judge Dredd creator John Wagner, and Frank Quietly, one of the world’s most sought-after comics artists, are among the top names appearing at this year’s Dundee Comics Day. They are just two of a number of star names from the world of comics lined up for the event, which will see talks, exhibitions, book signings and workshops take place as part of this year’s Dundee Literary Festival. Wagner started his long career as a comics writer at DC Thomson in Dundee before going on to revolutionise British comics in the late 1970s with the creation of Judge Dredd. He is the creator of Bogie Man, and the graphic novel A History of Violence, and has written for many of the major publishers in the US. Quietly has worked on New X-Men, We3, All-Star Superman, and Batman and Robin, as well as collaborating with some of the world’s top comics writers such as Mark Millar, Grant Morrison, and Alan Grant. His stylish artwork has made him one of the most celebrated artists in the comics industry. Wagner, Quietly and a host of other top industry talent will head to Dundee for the event, which will take place on Sunday, 30th October. Comics Day 2011 will be asking the question, what can comics teach us? Among the other leading industry figures giving their views on that subject will be former DC Thomson, Marvel, Dark Horse and DC Comics artist Cam Kennedy, Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design graduate Colin MacNeil, who worked on various 2000AD and Marvel and DC Comics publications, such as Conan and Batman, and Robbie Morrison, creator of Nikolai Dante, one of the most beloved characters in recent British comics. -

The Ultimate Foe

The Black Archive #14 THE ULTIMATE FOE By James Cooray Smith Published November 2017 by Obverse Books Cover Design © Cody Schell Text © James Cooray Smith, 2017 Range Editor: Philip Purser-Hallard James Cooray Smith has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding, cover or e-book other than which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publisher. 2 INTERMISSION: WHO IS THE VALEYARD In Holmes’ draft of Part 13, the Valeyard’s identity is straightforward. But it would not remain so for long. MASTER Your twelfth and final incarnation… and may I say you do not improve with age1. By the intermediate draft represented by the novelisation2 this has become: ‘The Valeyard, Doctor, is your penultimate reincarnation… Somewhere between your twelfth and thirteenth regeneration… and I may I say, you do not improve with age..!’3 The shooting script has: 1 While Robert Holmes had introduced the idea of a Time Lord being limited to 12 regenerations, (and thus 13 lives, as the first incarnation of a Time Lord has not yet regenerated) in his script for The Deadly Assassin, his draft conflates incarnations and regenerations in a way that suggests that either he was no longer au fait with how the terminology had come to be used in Doctor Who by the 1980s (e.g. -

Five Goes Mad in Stockbridge Fifth Doctor Peter Davison Chats About the New Season

ISSUE #8 OCTOBER 2009 FREE! NOT FOR RESALE JUDGE DREDD Writer David Bishop on taking another shot at ‘Old Stony Face’ DOCTOR WHO Scribe George Mann on Romana’s latest jaunt FIVE GOES MAD IN STOCKBRIDGE FIFTH DOCTOR PETER DAVISON CHATS ABOUT THE NEW SEASON PLUS: Sneak Previews • Exclusive Photos • Interviews and more! EDITORIAL Hello. More Vortex! Can you believe it? Of course studio session to make sure everyone is happy and that you can, you’re reading this. Now, if I sound a bit everything is running on time. And he has to do all those hyper here, it’s because there’s an incredibly busy time CD Extras interviews. coming up for Big Finish in October. We’ve already started recording the next season of Eighth Doctor What will I be doing? Well, I shall be writing a grand adventures, but on top of that there are more Lost finale for the Eighth Doctor season, doing the sound Stories to come, along with the Sixth Doctor and Jamie design for our three Sherlock Holmes releases, and adventures, the return of Tegan, Holmes and the Ripper writing a brand new audio series for Big Finish, which and more Companion Chronicles than you can shake may or may not get made one day! More news on that a perigosto stick at! So we’ll be in the studio for pretty story later, as they say… much the whole month. I say ‘we’… I actually mean ‘David Richardson’. He’s our man on the spot, at every Nick Briggs – executive producer SNEAK PREVIEWS AND WHISPERS Love Songs for the Shy and Cynical Bernice Summerfield A short story collection by Robert Shearman Secret Histories Rob Shearman is probably best known as a writer for Doctor This year’s Bernice Summerfield book is a short Who, reintroducing the Daleks for its BAFTA winning first stories collection, Secret Histories, a series of series, in an episode nominated for a Hugo Award. -

Doctor Who Party

The Annual DoctorCostume ComparisonWho Gallery Party Tim Harrison, Sr. as the 4th Doctor and Eric Stein as Captain Jack Harkness Jim Martin as the 9th Doctor Sarah Gilbertson as Raffalo (The End of the World) Esther Harrison as Harriet Jones (The Christmas Invasion) Karen Martin as Rose Tyler Jesse Stein as the 10th Doctor Katie Grzebin as Novice Hame (New Earth) Timothy Harrison, Jr. as the 10th Doctor and Lindsay Harrison as Rose Tyler (Tooth and Claw) JoLynn Graubart as Martha Jones and Matt Graubart as a Weeping Angel (Blink) Andrew Gilbertson as Prof. Yana (Utopia) Kayleigh Bickings as Lady Christina (Planet of the Dead) Joe Harrison as a Whifferdill (taking the form of Joe Harrison) (DWM: Voyager) 4, 9, 10, and everyone’s favorite Canine Computer... A bowl of Adipose... No substitute for a sonic blaster, but the 9th and 10th are fans... HOME 2010 The Annual DoctorCostume ComparisonWho Gallery Party Andrew Gilbertson as the 1st Doctor Hayley as a Dalek Camryn Bickings as ...Koquillion? (The Rescue) Timothy Harrison, Jr. as the 5th Doctor Jim Martin as the 9th Doctor Esther Harrison as Sarah Jane Smith BJ Johnson as a Weeping Angel (Blink) Sarah Gilbertson as Lucy Saxon (Last of the Time Lords) Katie Grzebin as Jenny (The Doctor’s Daughter) Karen Martin as the Visionary (The End of Time) Eric Stein as the post-regeneration 11th Doctor (The Eleventh Hour) Joe Harrison as the 11th Doctor Lindsay Harrison as Liz 10 (The Beast Below) JoLynn Graubart as Amy Pond and Matt Graubart as Rory the Roman (The Pandorica Opens) HOME 2009 2011 The Annual DoctorCostume ComparisonWho Gallery Party Andrew Gilbertson as the 2nd Doctor Joe Harrison as Jamie McCrimmon Timothy Harrison, Jr. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Accessing■i the World's UMI Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 882462 James Wright’s poetry of intimacy Terman, Philip S., Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1988 Copyright ©1988 by Terman, Philip S. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, M I 48106 JAMES WRIGHT'S POETRY OF INTIMACY DISSERTATION Presented In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Philip S. -

Doctor Who 4.8 - Return to Telos Pdf, Epub, Ebook

DOCTOR WHO 4.8 - RETURN TO TELOS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Nicholas Briggs,Anthony Lamb,Jamie Robertson,Tom Baker,Louise Jameson,John Leeson,Frazer Hines | none | 31 Aug 2015 | Big Finish Productions Ltd | 9781781783528 | English | Maidenhead, United Kingdom Doctor Who 4.8 - Return to Telos PDF Book Steve Tribe. About this product Product Information This range of two-part audio dramas stars Tom Baker reprising his most popular role as the Fourth Doctor from - with a number of his original TV companions. Follow us. Jenny T Colgan. However, they quickly realise that, if they do eliminate the Second Doctor, the Fourth will not exist and they will not be able to take control of the TARDIS, so they desist and the timelines return to normal. As they sleep, they take heir leave; seeing Telos up in the sky, a distant planet, the Doctor starts telling Leela about the Cybermen, wishing for her she'd never meet them. Things now go smoothly: the Doctor and Leela go fishing, they meet Geralk's robot, fish with it and then stay with him and Relly for dinner. You can learn more about how we plus approved third parties use cookies and how to change your settings by visiting the Cookies notice. The Doctor, persuaded, comes up with an idea, and tells Geralk to put on his robot control. As a result, the robot stops working and begins to repeat words about the last thing he was doing when it met them: going fishing. Are you happy to accept all cookies? This category only includes cookies that ensures basic functionalities and security features of the website. -

The Pandorica Opens / the Big Bang Sample

The Black Archive #44 THE PANDORICA OPENS / THE BIG BANG SAMPLE By Philip Bates Published June 2020 by Obverse Books Cover Design © Cody Schell Text © Philip Bates, 2020 Range Editors: Paul Simpson, Philip Purser-Hallard Philip Bates has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding, cover or e-book other than which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publisher. Also available #32: The Romans by Jacob Edwards #33: Horror of Fang Rock by Matthew Guerrieri #34: Battlefield by Philip Purser-Hallard #35: Timelash by Phil Pascoe #36: Listen by Dewi Small #37: Kerblam! by Naomi Jacobs and Thomas L Rodebaugh #38: The Sound of Drums / Last of the Time Lords by James Mortimer #39: The Silurians by Robert Smith? #40: The Underwater Menace by James Cooray Smith #41: Vengeance on Varos by Jonathan Dennis #42: The Rings of Akhaten by William Shaw #43: The Robots of Death by Fiona Moore This book is dedicated to my family and friends – to everyone whose story I’m part of. CONTENTS Overview Synopsis Introduction 1: Balancing the Epic and the Intimate 2: Myths and Fairytales 3: Anomalies 4: When Time Travel Wouldn’t Help 5: The Trouble with Time 6: Endings and Beginnings -

Doctor Who's Feminine Mystique

Doctor Who’s Feminine Mystique: Examining the Politics of Gender in Doctor Who By Alyssa Franke Professor Sarah Houser, Department of Government, School of Public Affairs Professor Kimberly Cowell-Meyers, Department of Government, School of Public Affairs University Honors in Political Science American University Spring 2014 Abstract In The Feminine Mystique, Betty Friedan examined how fictional stories in women’s magazines helped craft a societal idea of femininity. Inspired by her work and the interplay between popular culture and gender norms, this paper examines the gender politics of Doctor Who and asks whether it subverts traditional gender stereotypes or whether it has a feminine mystique of its own. When Doctor Who returned to our TV screens in 2005, a new generation of women was given a new set of companions to look up to as role models and inspirations. Strong and clever, socially and sexually assertive, these women seemed to reject traditional stereotypical representations of femininity in favor of a new representation of femininity. But for all Doctor Who has done to subvert traditional gender stereotypes and provide a progressive representation of femininity, its story lines occasionally reproduce regressive discourses about the role of women that reinforce traditional gender stereotypes and ideologies about femininity. This paper explores how gender is represented and how norms are constructed through plot lines that punish and reward certain behaviors or choices by examining the narratives of the women Doctor Who’s titular protagonist interacts with. Ultimately, this paper finds that the show has in recent years promoted traits more in line with emphasized femininity, and that the narratives of the female companion’s have promoted and encouraged their return to domestic roles.