The Mystical Journey in Sylvia Plath's Poetry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS in SCIENCE FICTION and FANTASY (A Series Edited by Donald E

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS IN SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY (a series edited by Donald E. Palumbo and C.W. Sullivan III) 1 Worlds Apart? Dualism and Transgression in Contemporary Female Dystopias (Dunja M. Mohr, 2005) 2 Tolkien and Shakespeare: Essays on Shared Themes and Language (ed. Janet Brennan Croft, 2007) 3 Culture, Identities and Technology in the Star Wars Films: Essays on the Two Trilogies (ed. Carl Silvio, Tony M. Vinci, 2007) 4 The Influence of Star Trek on Television, Film and Culture (ed. Lincoln Geraghty, 2008) 5 Hugo Gernsback and the Century of Science Fiction (Gary Westfahl, 2007) 6 One Earth, One People: The Mythopoeic Fantasy Series of Ursula K. Le Guin, Lloyd Alexander, Madeleine L’Engle and Orson Scott Card (Marek Oziewicz, 2008) 7 The Evolution of Tolkien’s Mythology: A Study of the History of Middle-earth (Elizabeth A. Whittingham, 2008) 8 H. Beam Piper: A Biography (John F. Carr, 2008) 9 Dreams and Nightmares: Science and Technology in Myth and Fiction (Mordecai Roshwald, 2008) 10 Lilith in a New Light: Essays on the George MacDonald Fantasy Novel (ed. Lucas H. Harriman, 2008) 11 Feminist Narrative and the Supernatural: The Function of Fantastic Devices in Seven Recent Novels (Katherine J. Weese, 2008) 12 The Science of Fiction and the Fiction of Science: Collected Essays on SF Storytelling and the Gnostic Imagination (Frank McConnell, ed. Gary Westfahl, 2009) 13 Kim Stanley Robinson Maps the Unimaginable: Critical Essays (ed. William J. Burling, 2009) 14 The Inter-Galactic Playground: A Critical Study of Children’s and Teens’ Science Fiction (Farah Mendlesohn, 2009) 15 Science Fiction from Québec: A Postcolonial Study (Amy J. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Accessing■i the World's UMI Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 882462 James Wright’s poetry of intimacy Terman, Philip S., Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1988 Copyright ©1988 by Terman, Philip S. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, M I 48106 JAMES WRIGHT'S POETRY OF INTIMACY DISSERTATION Presented In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Philip S. -

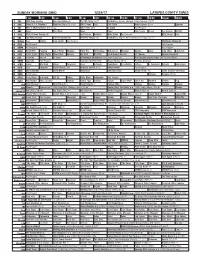

Sunday Morning Grid 12/24/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 12/24/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Los Angeles Chargers at New York Jets. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid PGA TOUR Action Sports (N) Å Spartan 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News Jack Hanna Ocean Sea Rescue Wildlife 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Los Angeles Rams at Tennessee Titans. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program Christmas Miracle at 18 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Milk Street Mexican Martha Jazzy Julia Child Chefs Life 28 KCET 1001 Nights 1001 Nights Mixed Nutz Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ 53rd Annual Wassail St. Thomas Holiday Handbells 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch A Firehouse Christmas (2016) Anna Hutchison. The Spruces and the Pines (2017) Jonna Walsh. 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Grandma Got Run Over Netas Divinas (TV14) Premios Juventud 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress K. -

The Collected Poems of Giorgio De Chirico

195 THE COLLECTED POEMS OF GIORGIO DE CHIRICO I Paris 1911-1915 1. Hopes1 Te astronomer poets are exuberant. Te day is radiant the public square flled with sunlight. Tey are leaning against the veranda. Music and love. Te incredibly beautiful woman. I would sacrifce my life for her velvet eyes. A painter has painted a huge red smokestack Tat a poet adores like a divinity. I remember that night of springtime and cadavers. Te river was carrying gravestones that have disappeared. Who still wants to live? Promises are more beautiful. So many fags are fying from the railroad station. Provided the clock does not stop A government minister is supposed to arrive. He is intelligent and mild he is smiling. He comprehends everything and at night by the glow of a smoking lamp While the warrior of stone dozes on the dark public square He writes sad passionate love letters. 1 Original title, Espoirs, published in “La révolution surréaliste”, n. 5, Paris 15 October 1925, p. 6. Te Éluard-Picasso Manuscripts (1911-1915), including theoretical writings and poems written in French and 29 drawings, constitute an essential testimony of de Chirico’s early theoretical and artistic considerations. (See J. de Sanna, Giorgio de Chirico - Disegno, Electa, Milan 2004, pp. 12-15). De Chirico arrived in Paris, from Florence, on 14 July 1911 and remained in the capital until late May 1915 when, called to arms, he returned to Italy with his brother Alberto Savinio. Initially in Paul Éluard’s collection, the manuscripts were later acquired by Picasso. Today they are conserved in ‘Fonds Picasso’ at Musée National Picasso, Paris. -

Doctor Who and the Politics of Casting Lorna Jowett, University

Doctor Who and the politics of casting Lorna Jowett, University of Northampton Abstract: This article argues that while long-running science fiction series Doctor Who (1963-89; 1996; 2005-) has started to address a lack of diversity in its casting, there are still significant imbalances. Characters appearing in single episodes are more likely to be colourblind cast than recurring and major characters, particularly the title character. This is problematic for the BBC as a public service broadcaster but is also indicative of larger inequalities in the television industry. Examining various examples of actors cast in Doctor Who, including Pearl Mackie who plays companion Bill Potts, the article argues that while steady progress is being made – in the series and in the industry – colourblind casting often comes into tension with commercial interests and more risk-averse decision-making. Keywords: colourblind casting, television industry, actors, inequality, diversity, race, LGBTQ+ 1 Doctor Who and the politics of casting Lorna Jowett The Britain I come from is the most successful, diverse, multicultural country on earth. But here’s my point: you wouldn’t know it if you turned on the TV. Too many of our creative decision-makers share the same background. They decide which stories get told, and those stories decide how Britain is viewed. (Idris Elba 2016) If anyone watches Bill and she makes them feel that there is more of a place for them then that’s fantastic. I remember not seeing people that looked like me on TV when I was little. My mum would shout: ‘Pearl! Come and see. -

Full Circle Sampler

The Black Archive #15 FULL CIRCLE SAMPLER By John Toon Second edition published February 2018 by Obverse Books Cover Design © Cody Schell Text © John Toon, 2018 Range Editors: James Cooray Smith, Philip Purser-Hallard John would like to thank: Phil and Jim for all of their encouragement, suggestions and feedback; Andrew Smith for kindly giving up his time to discuss some of the points raised in this book; Matthew Kilburn for using his access to the Bodleian Library to help me with my citations; Alex Pinfold for pointing out the Blake’s 7 episode I’d overlooked; Jo Toon and Darusha Wehm for beta reading my first draft; and Jo again for giving me the support and time to work on this book. John Toon has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding, cover or e-book other than which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publisher. 2 For you. Yes, you! Go on, you deserve it. 3 Also Available The Black Archive #1: Rose by Jon Arnold The Black Archive #2: The Massacre by James Cooray Smith The Black Archive #3: The Ambassadors of Death by LM Myles The Black Archive #4: Dark Water / Death in Heaven by Philip Purser-Hallard The Black Archive #5: Image of the Fendahl -

Eclosure of the Cybermen

I'VE BEEN FASCINATED, entranced and frightened by insects since childhood. They are small compared to humans and many other creatures with which we interact, but they do so much that we can’t. They can fly, of course – but most of all it's their ability to completely transform their physical state which bewitched me as a child and which I still read about today, absorbing exotic new vocabulary such as eclosure (the process of emerging from an abandoned exoskeleton) and exuvia (the abandoned, shrivelled ‘skin’). Much more is known now about metamorphosis than it was a few decades ago, but there are still competing accounts of what exactly happens when a larva pupates and how far the resulting adult insect is the same individual as the larva it was. Metamorphosis is a recurrent device in Doctor Who. Time Lord regeneration is an obvious example, but I was reminded of the Cybermen when I saw Sam's artwork and decided to put it on the cover of this issue. The picture (above left) is a homage to Male Figure with Skin Removed (above right) by Andreas Vesalius, a sixteenth-century Nether- landish anatomist,but rather than revealing bone and musculature, the skin is held at the arm of a Tenth Planet Cyberman, as if it has been newly cast off by the remade Mondasian whose new metallic organs harden in the night air. There are plenty of precedents within the broadcast series. The Wheel in Space featured Cybermen being transported in eggs within which they seemed to grow before hatching. -

Dark Water / Death in Heaven

The Black Archive #4 DARK WATER / DEATH IN HEAVEN By Philip Purser-Hallard 1 Published March 2016 by Obverse Books Cover Design © Cody Schell Text © Philip Purser-Hallard, 2016 Range Editor: Philip Purser-Hallard Philip would like to thank: Stuart Douglas at Obverse Books, for encouraging the Black Archive project from the start, and to the growing number of authors who have agreed to contribute to it; my ever-tolerant family for allowing me the time to write this book and edit the others in the series; everyone who read and commented on the manuscript, especially Jon Arnold and Alan Stevens; and Steven Moffat and all the creators of Doctor Who ancient and modern, for providing such an endlessly fascinating subject of investigation for us all. Philip Purser-Hallard has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding, cover or e-book other than which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent publisher. 2 To Rachel Churcher, who might enjoy it 3 CONTENTS Overview Synopsis Introduction: ‘So, What’s Happened?’ Chapter 1. ‘Everyone in London Just Clapped’: The Season Finale Chapter 2. ‘I’ve Been Up and Down Your Timeline’: Gathering the Threads Chapter 3. -

Dark Harvest © Copyright Games Workshop Limited 2019

• THE VAMPIRE GENEVIEVE • by Kim Newman DRACHENFELS GENEVIEVE UNDEAD BEASTS IN VELVET SILVER NAILS THE WICKED AND THE DAMNED A portmanteau novel by Josh Reynolds, Phil Kelly and David Annandale MALEDICTIONS An anthology by various authors THE HOUSE OF NIGHT AND CHAIN A novel by David Annandale CASTLE OF BLOOD A novel by C L Werner THE COLONEL’S MONOGRAPH A novella by Graham McNeill INVOCATIONS An anthology by various authors PERDITION’S FLAME An audio drama by Alec Worley CONTENTS Cover Backlist Title Page Warhammer Horror Chapter One Chapter Two Chapter Three Chapter Four Chapter Five Chapter Six Chapter Seven Chapter Eight Chapter Nine Chapter Ten Chapter Eleven Chapter Twelve Chapter Thirteen Chapter Fourteen Chapter Fifteen Chapter Sixteen Chapter Seventeen Chapter Eighteen Chapter Nineteen Chapter Twenty Chapter Twenty-One Chapter Twenty-Two Chapter Twenty-Three Chapter Twenty-Four Chapter Twenty-Five Chapter Twenty-Six About the Author An Extract from ‘Drachenfels’ A Black Library Publication Imprint eBook license A dark bell tolls in the abyss. It echoes across cold and unforgiving worlds, mourning the fate of humanity. Terror has been unleashed, and every foul creature of the night haunts the shadows. There is naught but evil here. Alien monstrosities drift in tomblike vessels. Watching. Waiting. Ravenous. Baleful magicks whisper in gloom-shrouded forests, spectres scuttle across disquiet minds. From the depths of the void to the blood-soaked earth, diabolic horrors stalk the endless night to feast upon unworthy souls. Abandon hope. Do not trust to faith. Sacrifices burn on pyres of madness, rotting corpses stir in unquiet graves. -

Mortal Danger

MORTAL DANGER Ann Aguirre —-1 Feiwel and Friends —0 New York —+1 1105-57735_ch00_1P.indd05-57735_ch00_1P.indd i 33/1/14/1/14 33:44:44 PPMM A FEIWEL AND FRIENDS BOOK An Imprint of Macmillan MORTAL DANGER. Copyright © 2014 by Ann Aguirre. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America by R. R. Donnelley & Sons Company, Harrisonburg, Virginia. For information, address Feiwel and Friends, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010. Feiwel and Friends books may be purchased for business or promotional use. For information on bulk purchases, please contact the Macmillan Corporate and Premium Sales Department at (800) 221- 7945 x5442 or by e-mail at [email protected]. Library of Congress Cataloging-in- Publication Data Available ISBN: 978- 1- 250- 02464- 0 Book design by . Feiwel and Friends logo designed by Filomena Tuosto First Edition: 2014 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 -1— macteenbooks.com 0— +1— 1105-57735_ch00_1P.indd05-57735_ch00_1P.indd iiii 33/1/14/1/14 33:44:44 PPMM For the survivors: That which did not kill us made us stronger. —-1 —0 —+1 1105-57735_ch00_1P.indd05-57735_ch00_1P.indd iiiiii 33/1/14/1/14 33:44:44 PPMM -1— 0— +1— 1105-57735_ch00_1P.indd05-57735_ch00_1P.indd iviv 33/1/14/1/14 33:44:44 PPMM DEATH WATCH was supposed to die at 5:57 a.m. I At least, I had been planning it for months. First I read up on the best ways to do it, then I learned the warning signs and made sure not to reveal any of them. -

He Awoke in the Dark. His Awakening Was Simple, Easy, Without Movement Save for the Eyes That Opened and Made Him Aware of Darkness

THE LITTLE LADY OF THE BIG HOUSE BY JACK LONDON CHAPTER I He awoke in the dark. His awakening was simple, easy, without movement save for the eyes that opened and made him aware of darkness. Unlike most, who must feel and grope and listen to, and contact with, the world about them, he knew himself on the moment of awakening, instantly identifying himself in time and place and personality. After the lapsed hours of sleep he took up, without effort, the interrupted tale of his days. He knew himself to be Dick Forrest, the master of broad acres, who had fallen asleep hours before after drowsily putting a match between the pages of “Road Town” and pressing off the electric reading lamp. Near at hand there was the ripple and gurgle of some sleepy fountain. From far off, so faint and far that only a keen ear could catch, he heard a sound that made him smile with pleasure. He knew it for the distant, throaty bawl of King Polo—King Polo, his champion Short Horn bull, thrice Grand Champion also of all bulls at Sacramento at the California State Fairs. The smile was slow in easing from Dick Forrest’s face, for he dwelt a moment on the new triumphs he had destined that year for King Polo on the Eastern livestock circuits. He would show them that a bull, California born and finished, could compete with the cream of bulls corn- fed in Iowa or imported overseas from the immemorial home of Short Horns. Not until the smile faded, which was a matter of seconds, did he reach out in the dark and press the first of a row of buttons. -

Dark Water / Laura Mcneal

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. Copyright © 2010 by Laura McNeal All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of Random House Children’s Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc. Visit us on the Web! www.randomhouse.com/teens Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at www.randomhouse.com/teachers Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data McNeal, Laura. Dark water / Laura McNeal. — 1st ed. p. cm. Summary: Living in a cottage on her uncle’s Southern California avocado ranch since her parents’ messy divorce, fifteen-year-old Pearl DeWitt meets and falls in love with an illegal migrant worker, and is trapped with him when wildfires approach his makeshift forest home. eISBN: 978-0-375-89720-7 [1. Wildfires—Fiction. 2. Illegal aliens—Fiction. 3. Homeless persons—Fiction. 4. Divorce—Fiction. 5. Cousins—Fiction. 6. Family life—California— Fiction. 7. California—Fiction.] I. Title. PZ7.M47879365Dar 2010 [Fic]—dc22 2009043249 Random House Children’s Books supports the First Amendment and celebrates the right to read. v3.1 For Tom Contents Cover Title Page Copyright Dedication Chapter One Chapter Two Chapter Three Chapter Four