The Kingdom of Childhood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thinking Digital: Archives and Glissant Studies in the Twenty-First Century

1 1 Thinking Digital: Archives and Glissant Studies in the Twenty-First Century Jeanne Jégousso Emily O’Dell The Library of Glissant Studies, an open-access website, centralizes infor- mation by and on the work of Caribbean writer Édouard Glissant (Martinique, 1928–France, 2011). Endorsed by literary executors Sylvie and Mathieu Glissant, this multilingual, multimedia website provides bibliographic information, repro- duces rare sources, connects numerous institutions, and includes the works of both renowned and emerging scholars in order to stimulate further research.The library chronicles all forms of academic work devoted to Glissant’s writings, such as doctoral dissertations, MA theses, articles, books, and conference presenta- tions.In this article,Jeanne Jégousso and Emily O’Dell address the origin, the evolution, and the challenges of the digital platform that was launched in March 2018. Martinican author Édouard Glissant (1928–2011) revolutionized contemporary literary thought while providing new ways to theorize and understand transnational exchanges thanks to his key notions of Relation, developed in his 1990 Poétique de la Relation (Poetics of Relation), and the Tout-monde (Whole-World), which was also the title of his 1993 novel. Drawing from the diverse philosophical, poetic, and oral traditions of Europe, Africa, and the Americas, Glissant questioned and reconsidered the very notion of national boundaries and cultural legacies in order to create a dialogue among civilizations across time and geographic borders. Toward the end of his life, Glissant became particularly preoccupied with the continu- ation of the work that the Canadian scholar Alain Baudot had completed in his Bibliogra- phie annotée d’Édouard Glissant (Annotated Bibliography of Édouard Glissant), which contains more than thirteen hundred references and sixty illustrations pertaining to Glis- sant’s work and its criticism. -

The Power to Say Who's Human

University at Albany, State University of New York Scholars Archive Africana Studies Honors College 5-2012 The Power to Say Who’s Human: Politics of Dehumanization in the Four-Hundred-Year War between the White Supremacist Caste System and Afrocentrism Sam Chernikoff Frunkin University at Albany, State University of New York Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/honorscollege_africana Part of the African Studies Commons Recommended Citation Frunkin, Sam Chernikoff, "The Power to Say Who’s Human: Politics of Dehumanization in the Four- Hundred-Year War between the White Supremacist Caste System and Afrocentrism" (2012). Africana Studies. 1. https://scholarsarchive.library.albany.edu/honorscollege_africana/1 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College at Scholars Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Africana Studies by an authorized administrator of Scholars Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Power to Say Who’s Human The Power to Say Who’s Human: Politics of Dehumanization in the Four-Hundred-Year War between the White Supremacist Caste System and Afrocentrism Sam Chernikoff Frumkin Africana Studies Department University at Albany Spring 2012 1 The Power to Say Who’s Human —Introduction — Race represents an intricate paradox in modern day America. No one can dispute the extraordinary progress that was made in the fifty years between the de jure segregation of Jim Crow, and President Barack Obama’s inauguration. However, it is equally absurd to refute the prominence of institutionalized racism in today’s society. America remains a nation of haves and have-nots and, unfortunately, race continues to be a reliable predictor of who belongs in each category. -

Ho Chi Minh - Intérieur.Indd 1 17/07/2019 15:34 Dans La Petite Collection Rouge

Ho Chi Minh - intérieur.indd 1 17/07/2019 15:34 Dans la Petite collection rouge : Paul Boccara, Le Capital de Marx Fidel Castro, L’Histoire m’acquittera Friedrich Engels, L’origine de la famille, de la propriété privée et de l’État Antonio Gramsci, Textes choisis Hô Chi Minh, Le procès de la colonisation française Paul Lafargue, Le droit à la paresse Patricia Latour, La révolution en chantant Patricia Latour, Kollontaï, La révolution, le féminisme, l’amour et la liberté Michael Löwy, Rosa Luxemburg, l’étincelle incendiaire Vladimir Ilitch Lénine, L’impérialisme, stade suprême du capitalisme Rosa Luxemburg, La révolution russe Rosa Luxemburg, Lettres et textes choisis Karl Marx et Friedrich Engels, Le manifeste du Parti communiste Karl Marx, Salaires, prix et profits Karl Marx, Lettres d’Alger et de la Côte d’Azur Karl Marx, Adresse à la Commune de Paris Charles Silvestre, Jaurès, la passion du journaliste © Le Temps des Cerises, éditeurs, 2019 77 boulevard Chanzy 93100 Montreuil www.letempsdescerises.net Ho Chi Minh - intérieur.indd 2 17/07/2019 15:34 Alain Ruscio Ho Chi Minh écrits et combats Ho Chi Minh - intérieur.indd 3 17/07/2019 15:34 Ho Chi Minh - intérieur.indd 4 17/07/2019 15:34 « Il y en a qui luttent quelques jours. Ils sont estimables. Il y en a qui luttent des années. Ils sont indispensables. Il y en a qui luttent toute leur vie. Ils sont irremplaçables ! » Bertold Brecht Ho Chi Minh - intérieur.indd 5 17/07/2019 15:34 Ho Chi Minh - intérieur.indd 6 17/07/2019 15:34 Préface 7 Préface Joseph Andras Voici donc cinquante ans qu’Hô Chi Minh a disparu. -

Claude Mckay's a Long Way from Home

Through a Black Traveler's Eyes: Claude McKay's A Long Way from Home Tuire Valkeakari Yale University Abstract: This essay analyzes Jamaican-born Claude McKay's discussion of racism(s) and nationalism(~) in his travelogue/autobiography A Long Way from Home ( 1937), in which he chronicles his sojourn in Europe and North Africa and addresses his complex relationship to the United States. Much of McKay's social analysis draws, as this essay establishes, on his observation that racism and nationalism tend to be intertwined and feed 011 each othe1: While describing his travels, McKay presents himselfas a bordercrosser who is "a bad nationalist" and an "internationalist" - a cosmopolitan whose home cannot be defined by any fixed national labels or by nationalist or racialist identity politics. This essay's dialogue with McKay's memoir ultimately reconstructs his difficult and of1-frustrated quest for democracy - the political condition that Ralph Ellison once eloquently equated with "man~· being at home in. the world." Key words: Claude McKay - nationalism - transnationalism - cosmopolitanism - race - racism - travel The way home we seek is that condition of man's being at home in the world, which is called love, and which we tenn democracy. - Ralph Elli son, "Brave Words for a Startling Occasion" I said I was born in the West Indies and lived in the United States and that I was an American, even though I was a British subject, but 1 preferred to think of myself as an internationalist. The chaoL1Sh said he didn't understand what was an internationalist. J laughed and said that an internationalist was a bad nationalist. -

A PSYCHOMETRIC EXAMINATION of the AFRICENTRIC SCALE Challenges in Measuring Afrocentric Values

10.1177/0021934704266596JOURNALCokley, Williams OF BLACK / A PSYCHOMETRIC STUDIES / JULY EXAMINATION 2005 ARTICLE A PSYCHOMETRIC EXAMINATION OF THE AFRICENTRIC SCALE Challenges in Measuring Afrocentric Values KEVIN COKLEY University of Missouri at Columbia WENDI WILLIAMS Georgia State University The articulation of an African-centered paradigm has increasingly become an important component of the social science research published on people of African descent. Although several instruments exist that operationalize different aspects of an Afrocentric philosophical paradigm, only one instru- ment, the Africentric Scale, explicitly operationalizes Afrocentric values using what is arguably the most commercial and accessible understanding of Afrocentricity, the seven principles of the Nguzu Saba. This study exam- ined the psychometric properties of the Africentric Scale with a sample of 167 African American students. Results of a factor analysis revealed that the Africentric Scale is best conceptualized as measuring a general di- mension of Afrocentrism rather than seven separate principles. The find- ings suggest that with continued research, the Africentric Scale will be an increasingly viable option among the handful of measures designed to assess some aspect of Afrocentric values, behavioral norms, and an African worldview. Keywords: African-centered psychology; Afrocentric cultural values For at least three decades, Black psychologists have devoted their lives to undo the racist and maleficent theory and practice of main- stream or European-centered psychological practice. Nobles (1986) succinctly surveys the work and conclusions of prominent European-centered psychologists and concludes that the European- centered approach to inquiry as well as the assumptions made con- JOURNAL OF BLACK STUDIES, Vol. 35 No. 6, July 2005 827-843 DOI: 10.1177/0021934704266596 © 2005 Sage Publications 827 828 JOURNAL OF BLACK STUDIES / JULY 2005 cerning people of African descent are inappropriate in understand- ing people of African descent. -

African Studies Association 59Th Annual Meeting

AFRICAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION 59TH ANNUAL MEETING IMAGINING AFRICA AT THE CENTER: BRIDGING SCHOLARSHIP, POLICY, AND REPRESENTATION IN AFRICAN STUDIES December 1 - 3, 2016 Marriott Wardman Park Hotel, Washington, D.C. PROGRAM COMMITTEE CHAIRS: Benjamin N. Lawrance, Rochester Institute of Technology William G. Moseley, Macalester College LOCAL ARRANGEMENTS COMMITTEE CHAIRS: Eve Ferguson, Library of Congress Alem Hailu, Howard University Carl LeVan, American University 1 ASA OFFICERS President: Dorothy Hodgson, Rutgers University Vice President: Anne Pitcher, University of Michigan Past President: Toyin Falola, University of Texas-Austin Treasurer: Kathleen Sheldon, University of California, Los Angeles BOARD OF DIRECTORS Aderonke Adesola Adesanya, James Madison University Ousseina Alidou, Rutgers University Souleymane Bachir Diagne, Columbia University Brenda Chalfin, University of Florida Mary Jane Deeb, Library of Congress Peter Lewis, Johns Hopkins University Peter Little, Emory University Timothy Longman, Boston University Jennifer Yanco, Boston University ASA SECRETARIAT Suzanne Baazet, Executive Director Kathryn Salucka, Program Manager Renée DeLancey, Program Manager Mark Fiala, Financial Manager Sonja Madison, Executive Assistant EDITORS OF ASA PUBLICATIONS African Studies Review: Elliot Fratkin, Smith College Sean Redding, Amherst College John Lemly, Mount Holyoke College Richard Waller, Bucknell University Kenneth Harrow, Michigan State University Cajetan Iheka, University of Alabama History in Africa: Jan Jansen, Institute of Cultural -

Post-War English Literature 1945-1990

Post-War English Literature 1945-1990 Sara Martín Alegre P08/04540/02135 © FUOC • P08/04540/02135 Post-War English Literature 1945-1990 Index Introduction............................................................................................... 5 Objectives..................................................................................................... 7 1. Literature 1945-1990: cultural context........................................ 9 1.1. The book market in Britain ........................................................ 9 1.2. The relationship between Literature and the universities .......... 10 1.3. Adaptations of literary works for television and the cinema ...... 11 1.4. The minorities in English Literature: women and post-colonial writers .................................................................... 12 2. The English Novel 1945-1990.......................................................... 14 2.1. Traditionalism: between the past and the present ..................... 15 2.2. Fantasy, realism and experimentalism ........................................ 16 2.3. The post-modern novel .............................................................. 18 3. Drama in England 1945-1990......................................................... 21 3.1. West End theatre and the new English drama ........................... 21 3.2. Absurdist drama and social and political drama ........................ 22 3.3. New theatre companies and the Arts Council ............................ 23 3.4. Theatre from the mid-1960s onwards ....................................... -

Sylvia Pankhurst's Sedition of 1920

“Upheld by Force” Sylvia Pankhurst’s Sedition of 1920 Edward Crouse Undergraduate Thesis Department of History Columbia University April 4, 2018 Seminar Advisor: Elizabeth Blackmar Second Reader: Susan Pedersen With dim lights and tangled circumstance they tried to shape their thought and deed in noble agreement; but after all, to common eyes their struggles seemed mere inconsistency and formlessness; for these later-born Theresas were helped by no coherent social faith and order which could perform the function of knowledge for the ardently willing soul. Their ardor alternated between a vague ideal and the common yearning of womanhood; so that the one was disapproved as extravagance, and the other condemned as a lapse. – George Eliot, Middlemarch, 1872 Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................... 2 Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................ 3 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 4 The End of Edwardian England: Pankhurst’s Political Development ................................. 12 After the War: Pankhurst’s Collisions with Communism and the State .............................. 21 Appealing Sedition: Performativity of Communism and Suffrage ....................................... 33 Prison and Release: Attempted Constructions of Martyrology -

A Critical Analysis of African-Centered Psychology: from Ism to Praxis

International Journal of Transpersonal Studies Volume 35 Issue 1 Article 9 1-1-2016 A Critical Analysis of African-Centered Psychology: From Ism to Praxis A. Ebede-Ndi California Institute of Integral Studies Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/ijts-transpersonalstudies Part of the Philosophy Commons, Psychology Commons, Religion Commons, and the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Ebede-Ndi, A. (2016). A critical analysis of African-centered psychology: From ism to praxis. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, 35 (1). http://dx.doi.org/10.24972/ijts.2016.35.1.65 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Special Topic Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Newsletters at Digital Commons @ CIIS. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Transpersonal Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CIIS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Critical Analysis of African-Centered Psychology: From Ism to Praxis A. Ebede-Ndi California Institute of Integral Studies San Francisco, CA, USA The purpose of this article is to critically evaluate what is perceived as shortcomings in the scholarly field of African-centered psychology and mode of transcendence, specifically in terms of the existence of an African identity. A great number of scholars advocate a total embrace of a universal African identity that unites Africans in the diaspora and those on the continent and that can be used as a remedy to a Eurocentric domination of psychology at the detriment of Black communities’ specific needs. -

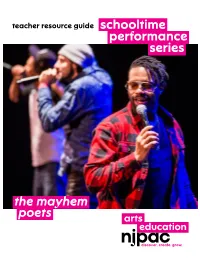

The Mayhem Poets Resource Guide

teacher resource guide schooltime performance series the mayhem poets about the who are in the performance the mayhem poets spotlight Poetry may seem like a rarefied art form to those who Scott Raven An Interview with Mayhem Poets How does your professional training and experience associate it with old books and long dead poets, but this is inform your performances? Raven is a poet, writer, performer, teacher and co-founder Tell us more about your company’s history. far from the truth. Today, there are many artists who are Experience has definitely been our most valuable training. of Mayhem Poets. He has a dual degree in acting and What prompted you to bring Mayhem Poets to the stage? creating poems that are propulsive, energetic, and reflective Having toured and performed as The Mayhem Poets since journalism from Rutgers University and is a member of the Mayhem Poets the touring group spun out of a poetry of current events and issues that are driving discourse. The Screen Actors Guild. He has acted in commercials, plays 2004, we’ve pretty much seen it all at this point. Just as with open mic at Rutgers University in the early-2000s called Mayhem Poets are injecting juice, vibe and jaw-dropping and films, and performed for Fiat, Purina, CNN and anything, with experience and success comes confidence, Verbal Mayhem, started by Scott Raven and Kyle Rapps. rhymes into poetry through their creatively staged The Today Show. He has been published in The New York and with confidence comes comfort and the ability to be They teamed up with two other Verbal Mayhem regulars performances. -

D. H. Lawrence and the Harlem Renaissance

‘You are white – yet a part of me’: D. H. Lawrence and the Harlem Renaissance A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2019 Laura E. Ryan School of Arts, Languages and Cultures 2 Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................... 3 Declaration ................................................................................................................. 4 Copyright statement ................................................................................................... 5 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................... 6 Introduction ................................................................................................................ 7 Chapter 1: ‘[G]roping for a way out’: Claude McKay ................................................ 55 Chapter 2: Chaos in Short Fiction: Langston Hughes ............................................ 116 Chapter 3: The Broken Circle: Jean Toomer .......................................................... 171 Chapter 4: ‘Becoming [the superwoman] you are’: Zora Neale Hurston................. 223 Conclusion ............................................................................................................. 267 Bibliography ........................................................................................................... 271 Word Count: 79940 3 -

Souleymane Bachir Diagne on Translation & Restitution

IN THE FOREGROUND: CONVERSATIONS ON ART & WRITING A Podcast from the Research and Academic Program (RAP) at the Clark Art Institute “A Gesture of Reciprocity”: Souleymane Bachir Diagne on Translation & Restitution Season 2, Episode 3 Recording date: OctoBer 14, 2020 Release date: FeBruary 23, 2021 Transcript Caro Fowler Welcome to In the Foreground: Conversations on Art & Writing. I am Caro Fowler, your host and director of the Research and Academic Program at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts. In this series of conversations, I talk with art historians and artists about what it means to write history and make art, and the ways in which making informs how we create not only our world, But also ourselves. In this episode, I speak with Lorraine O’Grady, an artist and critic whose installations, performances, and writings address issues of hyBridity and Black female suBjectivity, particularly the role these have played in the history of modernism. Lorraine discusses her long standing research into the relation of Charles Baudelaire and Jeanne Duval, the omissions of art historical scholarship and intersectional feminism, and the entanglement of personal and social histories in her work. Souleymane Bachir Diagne The translator, when she's dealing with two languages, and trying to give clarity to a meaning from a language to another language, that is this way of putting them in touch, to create an encounter between these two languages is an ethical gesture, it is a gesture of reciprocity. Caro Fowler Thank you for joining me today, Bachir. It's really nice to talk to you.