Interpreting the Shakers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Story of a Shaker Bible

Inspiration, Revelation, and Scripture: The Story of a Shaker Bible STEPHEN J. STEIN OR MORE than two hundred years the United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing, a religious commu- Fnity commonly known as the Shakers, has been involved with publishing. In 1790 'the first printed statement of Shaker theology' appeared anonymously in Bennington, Vermont, under the imprint of 'Haswell & Russell." Entitied A Concise Statement of the Principles of the Only True Church, according to the Gospel of the Present Appearance of Christ, this publication marked a departure from the pattern established by the founder, Ann Lee, an Englishwoman who came to America in 1774. Lee, herself illiter- ate, feared fixed statements of behef, and forbade her followers to write such documents. Within the space of two decades, however, the Shakers rejected Lee's counsel and turned with increasing fre- quency to the printing press in order to defend themselves against Earlier versions of this essay were presented at the Museum of Our National Heritage, Lexington, Massachusetts (1993), at the annual meeting of the American Society of Church History in San Erancisco (1994), and at Miami University, Oxford, Ohio (1995), under the auspices of the Arthur C. Wickenden Memorial Lectureship. My special thanlcs to Jerry Grant, who shared some of his research notes dealing with the Sacred Roll, which I have used in this version of the essay. I. See Mary L. Richmond, Shaker Literature: A Bibliography (2 vols., Hancock, Mass.: Shaker Community, Inc., 1977), i: 145-46. Richmond echoes the common judgment con- cerning the authorship of this tract, attributing it to Joseph Meacham, an early American convert to Shakerism. -

Enfield Shaker Museum Plan a Visit Today!

E NFIELD S HAKER M U S EU M 2019 PROGRAM GUIDE ENFIELD SHAKER MUSEUM PLAN A VISIT TODAY! Imagine a place so beautiful and serene that the Shakers called it DAILY ADMISSION “Chosen Vale.” General admission includes the intro- Nestled in a valley between Mt. ductory video program, guided tours, Assurance and Mascoma Lake, in exhibits, craft demonstrations, access Enfield, New Hampshire, the En- to other Shaker buildings, the Shak- field Shaker site has been cherished er Cemetery, the Shaker Herb and for over 225 years. At its peak in Production Garden, the Community the mid 19th century, the commu- Garden, the Feast Ground, and 15 nity was home to three “Families” miles of hiking trails. of Shakers. After 130 years of worship, communal living, farming, $12 adults and manufacturing, declining mem- $8 youth 11-17 bership forced the Shakers to close $3 children 6-10 their village and put it up for sale. Free children 5 and under Today the Enfield Shaker Village is Museum Members again a vibrant community. At its $10 Group Rate (6+) heart is the Enfield Shaker Muse- Plenty of Free Parking and Picnic Area um, which is dedicated to preserv- ing the long and rich legacy of the Enfield Shakers. MUSEUM HOURS TABLE OF CONTENTS May 1 - December 21 Become a Member ...................... 3 Facilities Rentals ........................ 3 Daily Youth Exploration Programs ...... 4 10 am - 5 pm Special Events .........................5-8 Center for Advanced Music ......... 8 December 22 - April 30 Monthly Offerings .................9-25 Open by Appointment Only Volunteer Opportunities ...........26 Program Registration ...............27 Please check our website Enfield Shaker Museum www.shakermuseum.org 447 NH Route 4A for our Holiday Hours Enfield, NH 03748 Phone: (603) 632-4346 [email protected] www.shakermuseum.org 2 SUppORT ENFIELD SHAKER MUSEUM Your investment today insures the future of this historic Shaker legacy tomorrow. -

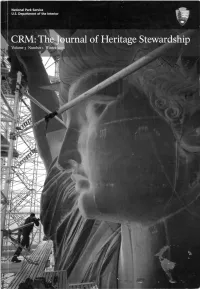

CRM: the Journal of Heritage Stewardship Volume 3 Number I Winter 2006 Editorial Board Contributing Editors

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior CRM: The Journal of Heritage Stewardship Volume 3 Number i Winter 2006 Editorial Board Contributing Editors David G. Anderson, Ph.D. Megan Brown Department of Anthropology, Historic Preservation Grants, University of Tennessee National Park Service Gordon W. Fulton Timothy M. Davis, Ph.D. National Park Service National Historic Sites Park Historic Structures and U.S. Department of the Interior Directorate, Parks Canada Cultural Landscapes, National Park Service Cultural Resources Art Gomez, Ph.D. Intermountain Regional Elaine Jackson-Retondo, Gale A. Norton Office, National Park Service Ph.D. Secretary of the Interior Pacific West Regional Office, Michael Holleran, Ph.D. National Park Service Fran P. Mainella Department of Planning and Director, National Park Design, University of J. Lawrence Lee, Ph.D., P.E. Service Colorado, Denver Heritage Documentation Programs, Janet Snyder Matthews, Elizabeth A. Lyon, Ph.D. National Park Service Ph.D. Independent Scholar; Former Associate Director, State Historic Preservation Barbara J. Little, Ph.D. Cultural Resources Officer, Georgia Archeological Assistance Programs, Frank G. Matero, Ph.D. National Park Service Historic Preservation CRM: The Journal of Program, University of David Louter, Ph.D. Heritage Stewardship Pennsylvania Pacific West Regional Office, National Park Service Winter 2006 Moises Rosas Silva, Ph.D. ISSN 1068-4999 Instutito Nacional de Chad Randl Antropologia e Historia, Heritage Preservation Sue Waldron Mexico Service, Publisher National Park Service Jim W Steely Dennis | Konetzka | Design SWCA Environmental Daniel J. Vivian Group, LLC Consultants, Phoenix, National Register of Historic Design Arizona Places/National Historic Landmarks, Diane Vogt-O'Connor National Park Service National Archives and Staff Records Administration Antoinette J. -

VALID BAPTISM Advisory List Prepared by the Worship Office and the Metropolitan Tribunal for the Archdiocese of Detroit

249 VALID BAPTISM Advisory list prepared by the Worship Office and the Metropolitan Tribunal for the Archdiocese of Detroit African Methodist Episcopal Patriotic Chinese Catholics Amish Polish National Church Anglican (valid Confirmation too) Ancient Eastern Churches Presbyterians (Syrian-Antiochian, Coptic, Reformed Church Malabar-Syrian, Armenian, Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Ethiopian) Day Saints (since 2001 known as the Assembly of God Community of Christ) Baptists Society of Pius X Christian and Missionary Alliance (followers of Bishop Marcel Lefebvre) Church of Christ United Church of Canada Church of God United Church of Christ Church of the Brethren United Reformed Church of the Nazarene Uniting Church of Australia Congregational Church Waldesian Disciples of Christ Zion Eastern Orthodox Churches Episcopalians – Anglicans LOCAL DETROIT AREA COMMUNITIES Evangelical Abundant Word of Life Evangelical United Brethren Brightmoor Church Jansenists Detroit World Outreach Liberal Catholic Church Grace Chapel, Oakland Lutherans Kensington Community Methodists Mercy Rd. Church, Redford (Baptist) Metropolitan Community Church New Life Ministries, St. Clair Shores Old Catholic Church Northridge Church, Plymouth Old Roman Catholic Church DOUBTFUL BAPTISM….NEED TO INVESTIGATE EACH Adventists Moravian Lighthouse Worship Center Pentecostal Mennonite Seventh Day Adventists DO NOT CELEBRATE BAPTISM OR HAVE INVALID BAPTISM Amana Church Society National David Spiritual American Ethical Union Temple of Christ Church Union Apostolic -

Handbook of Religious Beliefs and Practices

STATE OF WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS HANDBOOK OF RELIGIOUS BELIEFS AND PRACTICES 1987 FIRST REVISION 1995 SECOND REVISION 2004 THIRD REVISION 2011 FOURTH REVISION 2012 FIFTH REVISION 2013 HANDBOOK OF RELIGIOUS BELIEFS AND PRACTICES INTRODUCTION The Department of Corrections acknowledges the inherent and constitutionally protected rights of incarcerated offenders to believe, express and exercise the religion of their choice. It is our intention that religious programs will promote positive values and moral practices to foster healthy relationships, especially within the families of those under our jurisdiction and within the communities to which they are returning. As a Department, we commit to providing religious as well as cultural opportunities for offenders within available resources, while maintaining facility security, safety, health and orderly operations. The Department will not endorse any religious faith or cultural group, but we will ensure that religious programming is consistent with the provisions of federal and state statutes, and will work hard with the Religious, Cultural and Faith Communities to ensure that the needs of the incarcerated community are fairly met. This desk manual has been prepared for use by chaplains, administrators and other staff of the Washington State Department of Corrections. It is not meant to be an exhaustive study of all religions. It does provide a brief background of most religions having participants housed in Washington prisons. This manual is intended to provide general guidelines, and define practice and procedure for Washington State Department of Corrections institutions. It is intended to be used in conjunction with Department policy. While it does not confer theological expertise, it will, provide correctional workers with the information necessary to respond too many of the religious concerns commonly encountered. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ INAME HISTORIC Hancock Shaker Village__________________________________ AND/ORCOMMON Hancock Shaker Village STREET & NUMBER Lebanon Mountain Road ("U.S. Route 201 —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Hancock/Pittsfield _. VICINITY OF 1st STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 025 Berkshire 003 QCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE X.DISTRICT _PUBLIC -^OCCUPIED X_AGRICULTURE -XMUSEUM __BUILDING(S) X.RRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK _ STRUCTURE __BOTH XXWORK IN PROGRESS ^EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _JN PROCESS XXXYES . RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _ NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Shaker Community, Incorporated fprincipal owner) STREET& NUMBER P.O. Box 898 CITY. TOWN STATE Pittsfield VICINITY OF Mas s achus e 1.1. LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEoaETc. Berkshire County Registry of Deeds, Middle District STREETS NUMBER CITY, TOWN STATE Pittsfield Massachusetts REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Buildings Survey DATE 1931, 1959, 1945, 1960, 1962 ^FEDERAL _STATE _COUNTY ._LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Library of Congress, Division of Prints and Photographs CITY, TOWN STATE Washington DC DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE X_EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED _UNALTERED .^ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD _RUINS XXALTERED - restored —MOVED DATE_______ _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Hancock Shaker Village is located on a 1,000-acre tract of land extending north and south of Lebanon Mountain Road (U.S. -

Preparation for a Group Trip to Hancock Shaker Village Before Your Visit Lay a Foundation So That the Youngs

Preparation for a Group Trip to Hancock Shaker Village Before your visit Lay a foundation so that the youngsters know why they are going on this trip. Talk about things for the students to look for and questions that you hope to answer at the Village. Remember that the outdoor experiences at the Village can be as memorable an indoor ones. Information to help you is included in this package, and more is available online at www.hancockshakervillage.org. Plan to divide into small groups, and decide if specific focus topics will be assigned. Perhaps a treasure hunt for things related to a focus topic can make the experience more meaningful. Please review general museum etiquette with your class BEFORE your visit and ON the bus: • Please organize your class into small groups of 510 students per adult chaperone. • Students must stay with their chaperones at all times, and chaperones must stay with their assigned groups. • Please walk when inside buildings and use “inside voices.” • Listen respectfully when an interpreter is speaking. • Be respectful and courteous to other visitors. • Food or beverages are not allowed in the historic buildings. • No flash photography is allowed inside the historic buildings. • Be ready to take advantage of a variety of handson and mindson experiences! Arrival Procedure A staff member will greet your group at the designated Drop Off and Pick Up area – clearly marked by signs on our entry driveway and located adjacent to the parking lot and the Visitor Center. We will escort your group to the Picnic Area, which has rest rooms and both indoor and outdoor picnic tables. -

Guide I Bound Manuscripts

VOLUME I GUIDE TO BOUND SHAKER MANUSCRIPTS IN THE LIBRARY COLLECTION OF HANCOCK SHAKER VILLAGE Pittsfield, Massachusetts, 2001 Compiled and annotated by Dr. Magda Gabor-Hotchkiss Retired Coordinator of Library Collections Copyright © 2001 Hancock Shaker Village, Inc. CONTENTS PREPARER’S NOTE ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ORIGINAL BOUND MANUSCRIPTS ALFRED 2 ENFIELD, CT 2 GROVELAND, NY 3 HANCOCK, MA 3 HARVARD, MA 6 MOUNT LEBANON, NY 8 TYRINGHAM, MA 20 UNION VILLAGE, OH 21 UNKNOWN COMMUNITIES 21 COPIED BOUND MANUSCRIPTS CANTERBURY, NH 23 ENFIELD, CT 24 HANCOCK, MA 24 HARVARD, MA 26 MOUNT LEBANON, NY 27 NORTH UNION, OH 30 PLEASANT HILL, KY 31 SOUTH UNION, KY 32 WATERVLIET, NY 33 UNKNOWN COMMUNITY 34 MISCELLANEOUS 35 PREPARER'S NOTE: THE BOUND SHAKER MANUSCRIPTS A set of most remarkable documents, handwritten by the United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing, more commonly called the Shakers, was produced by their leaders, Elders of their Central (Lead), Bishopric, and Family Ministries; their Deacons, in charge of production of an endless variety of goods; their Trustees, in charge of their financial affairs. Thus these manuscripts - Ministerial and Family journals, yearbooks, diaries, Covenants, hymnals, are invaluable documents illuminating the concepts and views of Shakers on their religion, theology, music, spiritual life and visions, and their concerns and activities in community organization, membership, daily events, production of goods, financial transactions between Shaker societies and the outside world, their crafts and industries. For information pertaining to specific communities and Shaker individuals, only reference works that were most frequently used are listed: Index of Hancock Shakers - Biographical References, by Priscilla Brewer; Shaker Cities of Peace, Love, and Union: A History of the Hancock Bishopric, by Deborah E. -

South Union Messenger Kentucky Library - Serials

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® South Union Messenger Kentucky Library - Serials Winter 2006 South Union Messenger (Winter 2006) Kentucky Library Research Collections Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/su_messenger Part of the Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Kentucky Library Research Collections, "South Union Messenger (Winter 2006)" (2006). South Union Messenger. Paper 45. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/su_messenger/45 This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in South Union Messenger by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. J November 2006 South Union MESSENGER SHAKER MUSEUM AT SOUTH UNION Christmas atShakertownHoliday Market The holidays are here! Be among the first shoppers Center, located across the The popular Christmas at by purchasing tickets to the street from the 1824 Centre Shakertown Holiday Mar annual Preview Party on Friday, House. ket is set for December 1 December 1 at 7 p.m. The In lieu of a traditional and 2, 2006. event features a Starbucks admission fee, please bring Over 30 fine antique Coffee & Dessert Bar and canned food orlrionetary vendors and artisans will_ special holiday performances donations for the Auburn sen a wide array of holiday by the South Union Quartet Rural Fire Department wltl gifts perfect for everyone Tickets are $10 and can be T proceeds benefiting loca r030rvAri by calling the Shaker on youi' shopping list. families in need. ; From gorgeous antique Museum at 270-542-4167. -

96Th Annual NEMA Conference Boston/Cambridge November 19 – 21, 2014

96th Annual NEMA Conference Boston/Cambridge November 19 – 21, 2014 Picture of Health: Museums, Wellness, and Healthy Communities AUCTIONEERS AND APPRAISERS OF OBJECTS OF VALUE Major collections | Single items | World record prices Providing auction, appraisal, and deaccession services for museums and non-pro t institutions Skinner Appraisal Services | 508.970.3299 | [email protected] Boston Marlborough Miami www.skinnerinc.com MA/lic. #2304 How to Make the Most of NEMA 2014! CONFERENCE PROGRAM GUIDE 2014 PUBLICATION AWARD WINNERS Thanks for attending the 96th Annual NEMA Registration Area Conference. This year’s event is packed with more Look over the winners of this year’s NEMA information, more networking, and more fun than Publication Awards. See the best in design, ever. So where do you start? Here’s a quick “how- production, and communication. to” guide that will help you make the most of your conference experience. TALK BACK! Registration Area CONFERENCE APP Ask a question. Make your point. Take a time-out in Put the entire 2014 NEMA Conference at your our “Talk Back” area to ruminate on New England fingertips with our exclusive conference app. You’ll museum issues and provide input to NEMA. (Talk have it all: access to session information, floor plans, Back wall is courtesy of 42 Design Fab; visit them in evaluations, handouts, a conference game (courtesy Booth #42 in the Exhibit Hall.) of MuseumTrek by TrekSolver) and information about Boston/Cambridge. It is available in the App THE DEMONSTRATION STATION Store and Google Play. Download it now! You can Exhibit Hall, Thursday and Friday also access the app on all web-enabled devices. -

Peter Ayers, Defender of the Faith

American Communal Societies Quarterly Volume 5 Number 3 Pages 11-137 July 2011 Peter Ayers, Defender of the Faith Galen Beale Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hamilton.edu/acsq Part of the American Studies Commons This work is made available by Hamilton College for educational and research purposes under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 license. For more information, visit http://digitalcommons.hamilton.edu/about.html or contact [email protected]. Beale: Peter Ayers, Defender of the Faith Peter Ayers, Defender of the Faith By Galen Beale And as she turned and looked at an apple tree in full bloom, she exclaimed: — How beautiful this tree looks now! But some of the apples will soon fall off; some will hold on longer; some will hold on till they are half grown and will then fall off; and some will get ripe. So it is with souls that set out in the way of God. Many set out very fair and soon fall away; some will go further, and then fall off, some will go still further and then fall; and some will go through.1 New England was a hotbed of discontent in the second half of the eighteenth century. Both civil and religious events stirred its citizenry to action. Europeans wished to govern this new, resource-rich country, causing continual fighting, and new religions were springing up in reaction to the times. The French and Indian War had aligned the British with the colonists, but that alliance soon dissolved as the British tried to extract from its colonists the cost of protecting them. -

Brother Ricardo Belden Revisited

American Communal Societies Quarterly Volume 6 Number 1 Pages 3-21 January 2012 Brother Ricardo Belden Revisited Magda Gabor-Hotchkiss Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hamilton.edu/acsq Part of the American Studies Commons This work is made available by Hamilton College for educational and research purposes under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 license. For more information, visit http://digitalcommons.hamilton.edu/about.html or contact [email protected]. Gabor-Hotchkiss: Brother Ricardo Belden Revisited Brother Ricardo Belden Revisited1 By Magda Gabor-Hotchkiss In a recent issue of this journal, Darryl Charles Thompson provided an account of a “spirit song” presented in the Meeting House at Canterbury Shaker Village during the mid-1980s by his father, Charles “Bud” Thompson.2 The elder Mr. Thompson learned this song directly from Brother Ricardo Belden, then a resident of the Hancock Shakers’ Church Family. We acknowledge with pleasure the opportunity that his essay provided to share some treasured images from the collections of the Hancock Shaker Village Library, as well as to present additional information about Brother Ricardo’s life, his influence on musicologists and dance designers, and his role in attracting future Shakers. According to the Cathcart Membership File of Shakers, Ricardo Belden was born December 22, 1868, and died December 2, 1958, just shy of his ninetieth birthday.3 His date of birth has been the subject of some disagreement over the years, however, due to various small discrepancies among written records and his own statements. Among the different U.S. censuses listing Ricardo Belden, the 1900 census is the only one that asks for a specific month and year of birth.