CRM: the Journal of Heritage Stewardship Volume 3 Number I Winter 2006 Editorial Board Contributing Editors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Travel Summary

Travel Summary – All Trips and Day Trips Retirement 2016-2020 Trips (28) • Relatives 2016-A (R16A), September 30-October 20, 2016, 21 days, 441 photos • Anza-Borrego Desert 2016-A (A16A), November 13-18, 2016, 6 days, 711 photos • Arizona 2017-A (A17A), March 19-24, 2017, 6 days, 692 photos • Utah 2017-A (U17A), April 8-23, 2017, 16 days, 2214 photos • Tonopah 2017-A (T17A), May 14-19, 2017, 6 days, 820 photos • Nevada 2017-A (N17A), June 25-28, 2017, 4 days, 515 photos • New Mexico 2017-A (M17A), July 13-26, 2017, 14 days, 1834 photos • Great Basin 2017-A (B17A), August 13-21, 2017, 9 days, 974 photos • Kanab 2017-A (K17A), August 27-29, 2017, 3 days, 172 photos • Fort Worth 2017-A (F17A), September 16-29, 2017, 14 days, 977 photos • Relatives 2017-A (R17A), October 7-27, 2017, 21 days, 861 photos • Arizona 2018-A (A18A), February 12-17, 2018, 6 days, 403 photos • Mojave Desert 2018-A (M18A), March 14-19, 2018, 6 days, 682 photos • Utah 2018-A (U18A), April 11-27, 2018, 17 days, 1684 photos • Europe 2018-A (E18A), June 27-July 25, 2018, 29 days, 3800 photos • Kanab 2018-A (K18A), August 6-8, 2018, 3 days, 28 photos • California 2018-A (C18A), September 5-15, 2018, 11 days, 913 photos • Relatives 2018-A (R18A), October 1-19, 2018, 19 days, 698 photos • Arizona 2019-A (A19A), February 18-20, 2019, 3 days, 127 photos • Texas 2019-A (T19A), March 18-April 1, 2019, 15 days, 973 photos • Death Valley 2019-A (D19A), April 4-5, 2019, 2 days, 177 photos • Utah 2019-A (U19A), April 19-May 3, 2019, 15 days, 1482 photos • Europe 2019-A (E19A), July -

Reston, a Planned Community in Fairfax County, Virginia Reconnaissance Survey of Selected Individual Historic Resources and Eight Potential Historic Districts

Reston, A Planned Community in Fairfax County, Virginia Reconnaissance Survey of Selected Individual Historic Resources and Eight Potential Historic Districts PREPARED FOR: Virginia Department of Historic Resources AND Fairfax County PREPARED BY: Hanbury Preservation Consulting AND William & Mary Center for Archaeological Research Reston, A Planned Community in Fairfax County, Virginia Reconnaissance Survey of Selected Individual Historic Resources and Eight Potential Historic Districts W&MCAR Project No. 19-16 PREPARED FOR: Virginia Department of Historic Resources 2801 Kensington Avenue Richmond, Virginia 23221 (804) 367-2323 AND Fairfax County Department of Planning and Development 12055 Government Center Parkway Fairfax, VA 22035 (702) 324-1380 PREPARED BY: Hanbury Preservation Consulting P.O. Box 6049 Raleigh, NC 27628 (919) 828-1905 AND William & Mary Center for Archaeological Research P.O. Box 8795 Williamsburg, Virginia 23187-8795 (757) 221-2580 AUTHORS: Mary Ruffin Hanbury David W. Lewes FEBRUARY 8, 2021 CONTENTS Figures .......................................................................................................................................ii Tables ........................................................................................................................................ v Acknowledgments ....................................................................................................................... v 1: Introduction ..............................................................................................................................1 -

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers Asian Native Asian Native Am. Black Hisp Am. Total Am. Black Hisp Am. Total ALABAMA The Anniston Star........................................................3.0 3.0 0.0 0.0 6.1 Free Lance, Hollister ...................................................0.0 0.0 12.5 0.0 12.5 The News-Courier, Athens...........................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Lake County Record-Bee, Lakeport...............................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Birmingham News................................................0.7 16.7 0.7 0.0 18.1 The Lompoc Record..................................................20.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 The Decatur Daily........................................................0.0 8.6 0.0 0.0 8.6 Press-Telegram, Long Beach .......................................7.0 4.2 16.9 0.0 28.2 Dothan Eagle..............................................................0.0 4.3 0.0 0.0 4.3 Los Angeles Times......................................................8.5 3.4 6.4 0.2 18.6 Enterprise Ledger........................................................0.0 20.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 Madera Tribune...........................................................0.0 0.0 37.5 0.0 37.5 TimesDaily, Florence...................................................0.0 3.4 0.0 0.0 3.4 Appeal-Democrat, Marysville.......................................4.2 0.0 8.3 0.0 12.5 The Gadsden Times.....................................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Merced Sun-Star.........................................................5.0 -

Feasting and Communal Ritual in the Lower Mississippi Valley, Ad 700–1000

FEASTING AND COMMUNAL RITUAL IN THE LOWER MISSISSIPPI VALLEY, AD 700–1000 Megan Crandal Kassabaum A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Anthropology. Chapel Hill 2014 Approved by: Vincas P. Steponaitis C. Margaret Scarry Dale L. Hutchinson Brett H. Riggs Valerie Lambert © 2014 Megan Crandal Kassabaum ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Megan Crandal Kassabaum: Feasting and Communal Ritual in the Lower Mississippi Valley, AD 700–1000 (Under the direction of Vincas P. Steponaitis) This dissertation examines prehistoric activity at the Feltus site (22Je500) in Jefferson County, Mississippi, to elucidate how Coles Creek (AD 700–1200) platform mound sites were used. Data from excavations undertaken by the Feltus Archaeological Project from 2006 to 2012 support the conclusion that Coles Creek people utilized Feltus episodically for some 400 years, with little evidence of permanent habitation. More specifically, the ceramic, floral, and faunal data suggest that Feltus provided a location for periodic ritual events focused around food consumption, post-setting, and mound building. The rapidity with which the middens at Feltus were deposited and the large size of the ceramic vessels implies that the events occurring there brought together large groups of people for massive feasting episodes. The vessel form assemblage is dominated by open bowls and thus suggests an emphasis on food consumption, with less evidence for food preparation and virtually none for food storage. Overall, the ceramic assemblage emphasizes a great deal of continuity in the use of the Feltus landscape from the earliest occupation, during the Hamilton Ridge phase, through the latest, during the Balmoral phase. -

Rethinking Genocide: Violence and Victimhood in Eastern Anatolia, 1913-1915

Rethinking Genocide: Violence and Victimhood in Eastern Anatolia, 1913-1915 by Yektan Turkyilmaz Department of Cultural Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Orin Starn, Supervisor ___________________________ Baker, Lee ___________________________ Ewing, Katherine P. ___________________________ Horowitz, Donald L. ___________________________ Kurzman, Charles Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2011 i v ABSTRACT Rethinking Genocide: Violence and Victimhood in Eastern Anatolia, 1913-1915 by Yektan Turkyilmaz Department of Cultural Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Orin Starn, Supervisor ___________________________ Baker, Lee ___________________________ Ewing, Katherine P. ___________________________ Horowitz, Donald L. ___________________________ Kurzman, Charles An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2011 Copyright by Yektan Turkyilmaz 2011 Abstract This dissertation examines the conflict in Eastern Anatolia in the early 20th century and the memory politics around it. It shows how discourses of victimhood have been engines of grievance that power the politics of fear, hatred and competing, exclusionary -

Pridepages 2014

Pride2014 capepages cod and islands We’re Everywhere! LGBT Business, travel & relocation guide c ape c od and i slands Pridepages 2014 martha’s vineyard • nantucket south coast • south shore Nadia Pokrovskaya, D.M.D. DENTAL ARTS STUDIO OF CAPE COD 55 Oak Road, North Eastham, MA (508) 255-0557 ntistryBEYOND YOUR EXPECTATIONS OUR TEAM IS HERE TO MAKE YOU SMILE! • BOTOX • Periodontal Treatment • Dermal Fillers • Surgical Extractions • ZOOM Whitening • Root Canal Treatment • Invisalign • TMJ & Sleep Apnea • Sedation Therapy • Dental Implants • Removable Dentures • Porcelain Veneers • Geriatric Dental Care • Crowns and Bridges • Pediatric Dental Care • Cosmetic Dentistry • Emergency Dental • Oral Cancer Screening Treatment The doctor is available on-call after hours to treat all dental emergencies. www.CapeDentistry.com Big City Competitive Prices, Cape Cod Friendliness and Service 2014 BRZ View our new and pre-owned inventory: www.BeardSubaru.com SUBARU 24 RIDGEWOOD AVENUE HYANNIS 508-778-5066 www.PridepagesCapeCod.com 1 VISIT OUR KITCHEN & BATH SHOWROOM HYANNIS ORLEANS HONDA AUTO CENTER Your Local Community Dealers for Honda Products L ONG FELLOWDB.COM Hyannis Honda and Orleans Auto Center treat the needs of each individual customer with paramount concern. We know that you have high expectations, and as a car dealer we enjoy the challenge of meeting and exceeding those standards each and every time. HYANNIS HONDA ORLEANS AUTO CENTER 830 West Main Street 6 West Road Hyannis, MA 02601 Orleans, MA 02653 508.778.7878 508.240.7978 774-255-1709 -

Buried Treasures Central Florida Genealogical Society, Inc

Buried Treasures Central Florida Genealogical Society, Inc. P. O. Box 536309, Orlando, FL 32853-6309 Web Site: http://www.cfgs.org Editor: Betty Jo Stockton (407) 876-1688 Email: [email protected] The Central Florida Genealogical Society, Inc. meets monthly, September through May. Meetings are held at the Marks Street Senior Center on the second Thursday of each month at 7:30 p.m. Marks Street Senior Center is located at 99 E. Marks St, which is between Orange Ave. and Magnolia, 4 blocks north of East Colonial (Hwy 50). The Daytime Group meets year-round at 1:30 p.m. on Thursday afternoons bi-monthly (odd numbered months.) The Board meets year-round on the third Tuesday of each month at 6:30 p.m. at the Orlando Public Library. All are welcome to attend. Table of contents President’s Message. 2 Thoughts from your editor. 2 Funeral Home and Newspaper Research Can Be Astonishing. 3 Carey Hand Funeral Home Records Now Online. 5 Tracking Granddad: The elusive William Ernest JA(C)QUES............................. 7 David Nathaniel Leonidas HANCOCK 1864-1901. 9 German Research Helps. 10 Family History in a Bottle . found under an outhouse!. 12 Florida U.S. Military Personnel Who Died from Hostile Action in the Korean War, 1950-1957 (Including Missing and Captured). 13 Alvin Jefferson NYE, Sr.. 15 Cluster vs. Cluster Research Approach.. 17 Florida 1885 Census Now Online. 19 State Census - 1885 Orange County, Florida. 20 Index....................................................................... 22 Contributors to this issue Cathy Burnsed Sharon Lynch A.G. Conlon George Morgan Paul Enchelmeyer Elaine Powell Carla Heller Betty Jo Stockton Lynne Knorr Buried Treasures Central FL Genealogical Society Vol 36, No 4 - Fall 2005 1 President’s Message Thoughts from your editor Since this is January, I thought I’d give you a “state For the second time in six months, I’ve been of the society” message. -

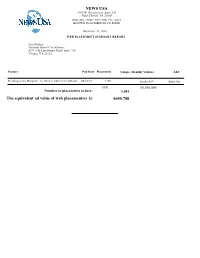

NEWS USA the Equivalent Ad Value of Web Placement(S)

NEWS USA 1069 W. Broadstreet, Suite 205 Falls Church, VA 22046 (800) 355 - 9500 / Fax (703) 734 - 6314 KNOWN PLACEMENTS TO DATE December 31, 2016 WEB PLACEMENT SUMMARY REPORT Lisa Fullam National Blood Clot Alliance 8321 Old Courthouse Road, Suite 255 Vienna, VA 22182 Feature Pub Date Placements Unique Monthly Visitors AEV Heading to the Hospital? Get Better. Don’t Get a Blood 08/10/16 1,001 50,058,999 $600,708 1001 50,058,999 Number of placements to date: 1,001 The equivalent ad value of web placement(s) is: $600,708 NEWS USA 1069 W. Broadstreet, Suite 205 Falls Church, VA 22046 (800) 355 - 9500 / Fax (703) 734 - 6314 KNOWN PLACEMENTS TO DATE December 31, 2016 National Blood Clot Alliance--Fullam WEB PLACEMENTS REPORT Feature: Heading to the Hospital? Get Better. Don’t Get a Blood Clot. Publication Date: 8/10/16 Unique Monthly Web Site City, State Date Vistors AEV 760 KFMB San Diego, CA 08/11/16 4,360 $52.32 96.5 Wazy ::: Today's Best Music, Lafayette Indiana Lafayette, IN 08/12/16 280 $3.36 Aberdeen American News Aberdeen, SD 08/11/16 14,800 $177.60 Abilene-rc.com Abilene, KS 08/11/16 0 $0.00 About Pokemon Go Cirebon, ID 09/08/16 0 $0.00 Advocate Tribune Online Granite Falls, MN 08/11/16 37,855 $454.26 aimmediatexas.com/ McAllen, TX 08/11/16 920 $11.04 Alerus Retirement Solutions Arden Hills, MN 08/12/16 28,400 $340.80 Alestle Live Edwardsville, IL 08/11/16 1,640 $19.68 Algona Upper Des Moines Algona, IA 08/11/16 680 $8.16 Amery Free Press. -

***Thesis Manuscript for Pr Uricchio

A Proposal for a Code of Ethics for Collaborative Journalism in the Digital Age: The Open Park Code by Florence H. J. T. Gallez B.A. English and Russian The University of London, 1996 M.S. Journalism Boston University, 1999 Submitted to the Program in Comparative Media Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology June 2012 © 2012 Florence Gallez. All rights reserved The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: __________________________________________________ Program in Comparative Media Studies June 2012 Certified by: ________________________________________________________ David L. Chandler Science Writer MIT News Office Accepted by: ________________________________________________________ William Charles Uricchio Professor of Comparative Media Studies Director, Comparative Media Studies 1 A Proposal for a Code of Ethics for Collaborative Journalism in the Digital Age: The Open Park Code by Florence H. J. T. Gallez Submitted To The Program in Comparative Media Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies ABSTRACT As American professional journalism with its established rules and values transitions to the little-regulated, ever-evolving world of digital news, few of its practitioners, contributors -

BOSTON CITY GUIDE @Comatbu CONTENTS

Tips From Boston University’s College of Communication BOSTON CITY GUIDE @COMatBU www.facebook.com/COMatBU CONTENTS GETTING TO KNOW BOSTON 1 MUSEUMS 12 Walking Franklin Park Zoo Public Transportation: The T Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum Bike Rental The JFK Library and Museum Trolley Tours Museum of Afro-American History Print & Online Resources Museum of Fine Arts Museum of Science The New England Aquarium MOVIE THEATERS 6 SHOPPING 16 LOCAL RADIO STATIONS 7 Cambridgeside Galleria Charles Street Copley Place ATTRACTIONS 8 Downtown Crossing Boston Common Faneuil Hall Boston Public Garden and the Swan Newbury Street Boats Prudential Center Boston Public Library Charlestown Navy Yard Copley Square DINING 18 Esplanade and Hatch Shell Back Bay Faneuil Hall Marketplace North End Fenway Park Quincy Market Freedom Trail Around Campus Harvard Square GETTING TO KNOW BOSTON WALKING BIKE RENTAL Boston enjoys the reputation of being among the most walkable Boston is a bicycle-friendly city with a dense and richly of major U.S. cities, and has thus earned the nickname “America’s interconnected street network that enables cyclists to make most Walking City.” In good weather, it’s an easy walk from Boston trips on relatively lightly-traveled streets and paths. Riding is the University’s campus to the Back Bay, Beacon Hill, Public Garden/ perfect way to explore the city, and there are numerous bike paths Boston Common, downtown Boston and even Cambridge. and trails, including the Esplanade along the Charles River. PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION: THE T Urban AdvenTours If you want to venture out a little farther or get somewhere a Boston-based bike company that offers bicycle tours seven days little faster, most of the city’s popular attractions are within easy a week at 10:00 a.m., 2:00 p.m., and 6:00 p.m. -

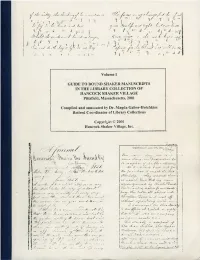

Guide I Bound Manuscripts

VOLUME I GUIDE TO BOUND SHAKER MANUSCRIPTS IN THE LIBRARY COLLECTION OF HANCOCK SHAKER VILLAGE Pittsfield, Massachusetts, 2001 Compiled and annotated by Dr. Magda Gabor-Hotchkiss Retired Coordinator of Library Collections Copyright © 2001 Hancock Shaker Village, Inc. CONTENTS PREPARER’S NOTE ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ORIGINAL BOUND MANUSCRIPTS ALFRED 2 ENFIELD, CT 2 GROVELAND, NY 3 HANCOCK, MA 3 HARVARD, MA 6 MOUNT LEBANON, NY 8 TYRINGHAM, MA 20 UNION VILLAGE, OH 21 UNKNOWN COMMUNITIES 21 COPIED BOUND MANUSCRIPTS CANTERBURY, NH 23 ENFIELD, CT 24 HANCOCK, MA 24 HARVARD, MA 26 MOUNT LEBANON, NY 27 NORTH UNION, OH 30 PLEASANT HILL, KY 31 SOUTH UNION, KY 32 WATERVLIET, NY 33 UNKNOWN COMMUNITY 34 MISCELLANEOUS 35 PREPARER'S NOTE: THE BOUND SHAKER MANUSCRIPTS A set of most remarkable documents, handwritten by the United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing, more commonly called the Shakers, was produced by their leaders, Elders of their Central (Lead), Bishopric, and Family Ministries; their Deacons, in charge of production of an endless variety of goods; their Trustees, in charge of their financial affairs. Thus these manuscripts - Ministerial and Family journals, yearbooks, diaries, Covenants, hymnals, are invaluable documents illuminating the concepts and views of Shakers on their religion, theology, music, spiritual life and visions, and their concerns and activities in community organization, membership, daily events, production of goods, financial transactions between Shaker societies and the outside world, their crafts and industries. For information pertaining to specific communities and Shaker individuals, only reference works that were most frequently used are listed: Index of Hancock Shakers - Biographical References, by Priscilla Brewer; Shaker Cities of Peace, Love, and Union: A History of the Hancock Bishopric, by Deborah E. -

Territoriality and Surveillance: Defensible Space and Low-Rise Public Housing Design, 1966-1976

Territoriality and Surveillance: Defensible Space and Low-Rise Public Housing Design, 1966-1976 Patricia A. Morton Abstract This essay investigates how theories of crime prevention through environmen- tal design influenced the architecture and planning of American public housing in the 1960s and 1970s. In this period, high crime rates were strongly associated with high-rise public housing, exemplified by St. Louis’s notorious Pruitt-Igoe complex. Analyzing four federally-subsidized housing projects, I show how ideas about the environment’s effect on human behavior, exemplified by Oscar New- man’s theory of “defensible space,” motivated experiments with low-rise, high- density public housing as alternatives to crime-ridden high-rises. Newman’s theory held that correct design could solve the crime problem by increasing a sense of territoriality among residents and encouraging their surveillance of pub- lic spaces. The projects analyzed here had variable success in preventing crime and fostering community among their residents, raising questions about the effi- cacy of architecture and planning alone to produce security and constitute com- munity in public housing. By the mid-1960s, alarm over conditions in high-rise public hous- 1 1 See National Com- ing in the United States was acute. Increased crime and deteriorating mission on Urban Prob- buildings belied the promise of urban renewal and public housing pro- lems; Wright 220-39. grams to eliminate blight and improve living standards for the poor and 2 Among recent critical 2 histories of public hous- the working class. Fear of crime was widespread among residents of ing, see Bloom, Umbach, subsidized housing and was strongly associated with the architecture of and Vale; Hunt; Vale.