Brother Ricardo Belden Revisited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

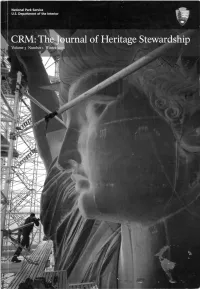

CRM: the Journal of Heritage Stewardship Volume 3 Number I Winter 2006 Editorial Board Contributing Editors

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior CRM: The Journal of Heritage Stewardship Volume 3 Number i Winter 2006 Editorial Board Contributing Editors David G. Anderson, Ph.D. Megan Brown Department of Anthropology, Historic Preservation Grants, University of Tennessee National Park Service Gordon W. Fulton Timothy M. Davis, Ph.D. National Park Service National Historic Sites Park Historic Structures and U.S. Department of the Interior Directorate, Parks Canada Cultural Landscapes, National Park Service Cultural Resources Art Gomez, Ph.D. Intermountain Regional Elaine Jackson-Retondo, Gale A. Norton Office, National Park Service Ph.D. Secretary of the Interior Pacific West Regional Office, Michael Holleran, Ph.D. National Park Service Fran P. Mainella Department of Planning and Director, National Park Design, University of J. Lawrence Lee, Ph.D., P.E. Service Colorado, Denver Heritage Documentation Programs, Janet Snyder Matthews, Elizabeth A. Lyon, Ph.D. National Park Service Ph.D. Independent Scholar; Former Associate Director, State Historic Preservation Barbara J. Little, Ph.D. Cultural Resources Officer, Georgia Archeological Assistance Programs, Frank G. Matero, Ph.D. National Park Service Historic Preservation CRM: The Journal of Program, University of David Louter, Ph.D. Heritage Stewardship Pennsylvania Pacific West Regional Office, National Park Service Winter 2006 Moises Rosas Silva, Ph.D. ISSN 1068-4999 Instutito Nacional de Chad Randl Antropologia e Historia, Heritage Preservation Sue Waldron Mexico Service, Publisher National Park Service Jim W Steely Dennis | Konetzka | Design SWCA Environmental Daniel J. Vivian Group, LLC Consultants, Phoenix, National Register of Historic Design Arizona Places/National Historic Landmarks, Diane Vogt-O'Connor National Park Service National Archives and Staff Records Administration Antoinette J. -

Guide I Bound Manuscripts

VOLUME I GUIDE TO BOUND SHAKER MANUSCRIPTS IN THE LIBRARY COLLECTION OF HANCOCK SHAKER VILLAGE Pittsfield, Massachusetts, 2001 Compiled and annotated by Dr. Magda Gabor-Hotchkiss Retired Coordinator of Library Collections Copyright © 2001 Hancock Shaker Village, Inc. CONTENTS PREPARER’S NOTE ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ORIGINAL BOUND MANUSCRIPTS ALFRED 2 ENFIELD, CT 2 GROVELAND, NY 3 HANCOCK, MA 3 HARVARD, MA 6 MOUNT LEBANON, NY 8 TYRINGHAM, MA 20 UNION VILLAGE, OH 21 UNKNOWN COMMUNITIES 21 COPIED BOUND MANUSCRIPTS CANTERBURY, NH 23 ENFIELD, CT 24 HANCOCK, MA 24 HARVARD, MA 26 MOUNT LEBANON, NY 27 NORTH UNION, OH 30 PLEASANT HILL, KY 31 SOUTH UNION, KY 32 WATERVLIET, NY 33 UNKNOWN COMMUNITY 34 MISCELLANEOUS 35 PREPARER'S NOTE: THE BOUND SHAKER MANUSCRIPTS A set of most remarkable documents, handwritten by the United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing, more commonly called the Shakers, was produced by their leaders, Elders of their Central (Lead), Bishopric, and Family Ministries; their Deacons, in charge of production of an endless variety of goods; their Trustees, in charge of their financial affairs. Thus these manuscripts - Ministerial and Family journals, yearbooks, diaries, Covenants, hymnals, are invaluable documents illuminating the concepts and views of Shakers on their religion, theology, music, spiritual life and visions, and their concerns and activities in community organization, membership, daily events, production of goods, financial transactions between Shaker societies and the outside world, their crafts and industries. For information pertaining to specific communities and Shaker individuals, only reference works that were most frequently used are listed: Index of Hancock Shakers - Biographical References, by Priscilla Brewer; Shaker Cities of Peace, Love, and Union: A History of the Hancock Bishopric, by Deborah E. -

The Church Family Orchard of the Watervliet Shaker Community

The Church Family Orchard of the Watervliet Shaker Community Elizabeth Shaver Illustrations by Elizabeth Lee PUBLISHED BY THE SHAKER HERITAGE SOCIETY 25 MEETING HOUSE ROAD ALBANY, N. Y. 12211 www.shakerheritage.org MARCH, 1986 UPDATED APRIL, 2020 A is For Apple 3 Preface to 2020 Edition Just south of the Albany International called Watervliet, in 1776. Having fled Airport, Heritage Lane bends as it turns from persecution for their religious beliefs from Ann Lee Pond and continues past an and practices, the small group in Albany old cemetery. Between the pond and the established the first of what would cemetery is an area of trees, and a glance eventually be a network of 22 communities reveals that they are distinct from those in the Northeast and Midwest United growing in a natural, haphazard fashion in States. The Believers, as they called the nearby Nature Preserve. Evenly spaced themselves, had broken away from the in rows that are still visible, these are apple Quakers in Manchester, England in the trees. They are the remains of an orchard 1750s. They had radical ideas for the time: planted well over 200 years ago. the equality of men and women and of all races, adherence to pacifism, a belief that Both the pond, which once served as a mill celibacy was the only way to achieve a pure pond, and this orchard were created and life and salvation, the confession of sins, a tended by the people who now rest in the devotion to work and collaboration as a adjacent cemetery, which dates from 1785. -

Sufficient Unto Themselves: Life and Economy Among the Shakers in Nineteenth-Century Rural Maine

Maine History Volume 40 Number 2 Lynching Jim Cullen Article 2 6-1-2001 Sufficient Unto Themselves: Life and Economy Among the Shakers in Nineteenth-Century Rural Maine Mark B. Lapping University of Southern Maine Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistoryjournal Part of the Cultural History Commons, History of Religion Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Lapping, Mark B.. "Sufficient Unto Themselves: Life and Economy Among the Shakers in Nineteenth- Century Rural Maine." Maine History 40, 2 (2001): 86-112. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/ mainehistoryjournal/vol40/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Shaker Meeting House, Sabbathday Lake, 1962. Shaker communities adhered to a philosophy of simplicity and self-sufficiency, but they also responded successfully to the nation’s emerging commercial and industrial economy. Thus they forged an accommodation between the demands of the external world and their own philosophy of spiri tual self-discipline. Maine Historic Buildings Survey Photo, Maine Historical Society. SUFFICIENT UNTO THEMSELVES: LIFE AND ECONOMY AMONG THE SHAKERS IN NINETEENTH- CENTURY RURAL MAINE M a r k B. La p p in g Community self-sufficiency was an ideal that both defined and in formed the Shaker experience in America. During the nineteenth century the Shakers at Sabbathday Lake Colony in New Gloucester, Maine— today the last remaining Shaker Colony in the nation— de veloped a sophisticated economic system that combined agricultural innovation, a far-reaching market-based trade in seeds, herbs, and medicinals, mill-based and home manufacturers, and “fancy goods” to supply the developing tourist sector. -

Two Centuries of Visitors to Shaker Villages

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Open Access Dissertations 2-2010 Seeking Shakers: Two Centuries of Visitors to Shaker Villages Brian L. Bixby University of Massachusetts Amherst, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Bixby, Brian L., "Seeking Shakers: Two Centuries of Visitors to Shaker Villages" (2010). Open Access Dissertations. 157. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations/157 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SEEKING SHAKERS: TWO CENTURIES OF VISITORS TO SHAKER VILLAGES A Dissertation Presented by BRIAN L. BIXBY Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY February 2010 Department of History © Copyright by Brian L. Bixby 2010 All Rights Reserved SEEKING SHAKERS: TWO CENTURIES OF VISITORS TO SHAKER VILLAGES A Dissertation Presented by BRIAN L. BIXBY Approved as to style and content by: ____________________________________ David Glassberg, Chair ____________________________________ Heather Cox Richardson, Member ____________________________________ Mario S. De Pillis, Member ____________________________________ H. Martin Wobst, Member __________________________________________ Audrey Altstadt, Department Chair Department of History DEDICATION My parents, Rudolph Varnum Bixby and Isabel Campbell Bixby, both fostered my love of history. I wish my father had lived to see the end of this work. This dissertation is dedicated to the both of them. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In my case, as for many others, the doctoral dissertation represents the sum of many, many years of education, conversation, and reading. -

Identity, Place, Religion, and Narrative at New Lebanon Shaker Village 1759-1861 by Marcus Réginald Létourneau

HOLY MOUNT: Identity, Place, Religion, and Narrative at New Lebanon Shaker Village 1759-1861 by Marcus Réginald Létourneau A thesis submitted to the Department of Geography in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University at Kingston Kingston, Ontario, Canada May 2009 copyright© Marcus Réginald Létourneau i ABSTRACT While the Shakers are associated in North American with simplicity and communalism, an examination of Shaker history reveals a dynamic and complex society. Shaker life was structured by a powerful metanarrative: the Shakers were the ‘Chosen People of God,’ who lived in ‘His Promised Land.’ This narrative, which is profoundly geographical due to its intertwining of people with place, was not static in its interpretation. Nevertheless, it served as the basis for the discourses concerning the most appropriate means to live in the World, but not be of it. Few geographers have examined religiosity and spirituality systematically. This research highlights the interaction between religiosity, identity, place, and narrative as an essential element of the human condition. Religiosity is expressed through narratives and rituals and buttresses a sense of identity and belonging in place. Particular expressions of the Shaker covenantal narrative were shaped by the places in which the Shakers existed. This work examines the Shaker experience at New Lebanon Shaker Village (New York) focusing on the antebellum period. It examines the context in which the Shakers existed, the shifts in the interpretations of the Shaker covenantal narratives, and the means by which the Shaker leadership disseminated their ideas. ii For Matthew Emile: “I must study politics and war that my sons may have the liberty to study mathematics and philosophy. -

Guide V Shaker Owned Books

Volume V SHAKERS’ BEST FRIENDS: GUIDE TO THE SHAKER-OWNED BOOKS IN THE LIBRARY COLLECTIONS OF HANCOCK SHAKER VILLAGE Compiled and annotated by Magda Gabor-Hotchkiss Retired Coordinator of Library Collections Copyright 2010 Hancock Shaker Village, Inc. Pittsfield, Massachusetts 1 IN TRIBUTE TO THE SHAKERS AT SABBATHDAY LAKE, MAINE, SISTER FRANCES CARR, BROTHER ARNOLD HADD, AND SISTER JUNE CARPENTER. IN CELEBRATION OF THE FIFTIETH ANNIVERSARY OF HANCOCK SHAKER VILLAGE: 1960-2010 IN LOVING MEMORY OF ROLLIN D. HOTCHKISS, 1911-2004: TIRELESS VOLUNTEER, PROGRAMMER, AND MANAGER OF THE DATABASE AT THE LIBRARY, HANCOCK SHAKER VILLAGE. 2 O! Childhood! How thy memories cling To riper Years. Dear Book From which I learned to read, And learned to think and Learned to live! Stay with me! And shouldst thou stray, Return to Anna Dodgson 1876 Anna Dodgson, teacher and family deaconess: Church Family, Mount Lebanon, New York 3 CONTENTS FOREWORD 7 PREFACE 8 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 9 INTRODUCTION 10 BOOKLIST 22 HANCOCK: BOOKS FOR ADULTS BIOGRAPHY/AUTOBIOGRAPHY 22 BOOKKEEPING 26 ECONOMICS 26 FICTION/POETRY 27 GOVERNMENT/CHILDREN/WOMEN 33 HISTORY 33 MEDICINE 35 MUSIC 35 PAINTING 40 PERIODICALS 40 PHILOSOPHY 40 REFERENCE/DICTIONARIES 41 RELIGION/BIBLES/RELIGIOUS LIFE 42 THEOLOGY 46 TRAVEL 48 HANCOCK: TEXTBOOKS FOR TEACHERS AND/OR STUDENTS ALGEBRA/ARITHMETIC/GEOMETRY 49 BOOKKEEPING 49 EDUCATION 49 ENGLISH GRAMMAR 50 ENGLISH READERS 50 ENGLISH SPELLERS 51 HISTORY FOR CHILDREN 51 MUSIC 51 RELIGION 52 SUNDAY SCHOOL/CATECHISM 52 TRAVEL 53 MOUNT LEBANON: BOOKS FOR ADULTS -

Guide II Unbound Manuscripts

Volume II GUIDE TO UNBOUND SHAKER MANUSCRIPTS IN THE LIBRARY COLLECTION OF HANCOCK SHAKER VILLAGE Pittsfield, Massachusetts, 2001 Compiled and annotated by Dr. Magda Gabor-Hotchkiss Retired Coordinator of Library Collections Copyright © 2001 Hancock Shaker Village, Inc. PREPARER'S NOTE: THE UNBOUND SHAKER MANUSCRIPT COLLECTION These manuscripts are invaluable documents illuminating the concepts and views of Shakers on their religious beliefs and practices, music, spiritual life and visions, as well as their concerns and activities in community organization, membership, education system, daily events, production of goods, their crafts and industries, and financial transactions. They include correspondence between their communities and between the Society and the outside world. For information pertaining to specific communities and Shaker individuals, we list here only reference works that were most frequently used: Maps of the Shaker West: A Journey of Discovery, by Martha Boice, Dale Covington, Richard Spence, 1997; Index of Hancock Shakers - Biographical References, by Priscilla Brewer; Shaker Cities of Peace, Love, and Union: A History of the Hancock Bishopric, by Deborah E. Burns, 1993; Shaker Your Plate: of Shaker Cooks and Cooking, by Sr. Frances A. Carr, 1985; Shaker Village Views, by Robert P. Emlen, 1987, The Shaker Image, by Elmer R. Pearson and Julia Neal, Second & Annotated edition, by Magda Gabor-Hotchkiss, 1994; Shaker Furniture Makers, by Jerry V. Grant and Douglas R. Allen, 1989; Seen and Received: The Shakers' Private Art, by Sharon Duane Koomler, 2000; Gospel Ministry, by Stephen Paterwic and Brother Arnold Hadd, in THE SHAKER QUARTERLY, Vol. 24, Nos. 1-4, 1996; Gift Drawing and Gift Song, by Daniel W. -

Interpreting the Shakers

49 INTERPRETING THE SHAKERS Interpreting the Shakers: Opening the Villages to the Public, 1955-1965' by William D. Moore In 1962, journalist Richard Shanor, writing in the magazine Travel, reported on a booming subfield of heritage tourism. "Today," he wrote, "an increasing number of visitors each year are discovering... the fascination of Shaker history, the beauty of Shaker craftsmanship, and the amazing number of ways Shaker hands and minds have contributed to the American heritage.'" Shanor and the editors of Travel recognized the fruits of the efforts of individuals from New Hampshire to Kentucky who were opening Shaker villages to the public as heritage sites. Established in North America at the end of the 18th century, the Shakers were a religious society with historical roots in the British Isles. Under the leadership of prophet Mother Ann Lee and her successor Joseph Meacham, the group, formally known as the United Society of Believers in Christ's Second Appearing, congregated in celibate, communitarian villages and lived according to a set of strictures, known as the "Millennial Laws," which guided both public and private behavior. According to these codes, all economic resources were shared, individuals worked for the common good, and pairs of male and female leaders attempted to steer the community to spiritual perfection and economic self-sufficiency. The Millennial Laws, grounded in Protestant avoidance of temptation and abhorrence of excess, also guided believers in their material life, leading to architecture and furniture that tended away from extravagant design and ornamentation. Following the Second Great Awakening, the society grew to comprise 18 villages located from Maine to Kentucky. -

Robert Cushman

Obituaries 27 Among other interests, Amy Bess was a long-term trustee of Berkshire Medical Center, the Berkshire Museum, Miss Hall's School, the Massachusetts Audubon Society, and the Shaker Mu- seum and Library (Old Chatham, New York). She received hon- orary degrees from Williams College, North Adams State Col- lege, Rhode Island School of Design, and Muhlenberg College. As a member of AAS, she attended at least five annual or semi- annual meetings and was often in touch with the Society, which she presented with several volumes. One was her own book 'The Shaker Image,' and another Mary Richmond's bibliography of Shaker literature, which Amy Bess published. The arrival of the latter volume led Marcus McCorison, librarian and president from i960 to 1992, to observe that the American Antiquarian So- ciety has one of the strongest collections of early American printed material on the Shakers. Amy Bess Miller leaves a daughter. Margo Miller of Boston, and three sons, Kelton B. Miller II of Shaftsbury, Vermont, Mi- chael G. Miller and Mark C. Miller of Pittsfield. Her sister Mar- gery Adams of Charlotte, North Carolina, five grandchildren, and three great-grandchildren also survive her. A memorial ser- vice was held at Hancock Shaker Village. Robert C. Achorn ROBERT CUSHMAN Robert Cushman, businessman, statesman, and Worcester civic leader, died on January 7, 2003, at the age of eighty-six. Bob grad- uated from Phillips Andover Academy and Dartmouth College. He was a good student and athlete, having been captain of swim- ming at Dartmouth. Soon after college. Bob married Mary 'Polly' Shorey after wooing her at Smith College. -

A Finding Aid to the Dorothy C. Miller Papers, 1853-2013, Bulk 1920-1996, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Dorothy C. Miller Papers, 1853-2013, bulk 1920-1996, in the Archives of American Art Stephanie Ashley, Barbara Aikens, and Hilary Price Funding for the processing of this collection was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art March 2011 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical Note............................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 3 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 5 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 5 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 8 Series 1: Biographical Material, 1917-1986............................................................. 8 Series 2: Correspondence and Subject Files, circa 1912-1992............................... 9 Series 3: Rockefeller Family -

Daughter of the Shakers: the Story of Eleanor Brooks Fairs

American Communal Societies Quarterly Volume 3 Number 4 Pages 187-205 October 2009 Daughter of the Shakers: The Story of Eleanor Brooks Fairs Johanne Grewell Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hamilton.edu/acsq Part of the American Studies Commons This work is made available by Hamilton College for educational and research purposes under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 license. For more information, visit http://digitalcommons.hamilton.edu/about.html or contact [email protected]. Grewell: Daughter of the Shakers: The Story of Eleanor Brooks Fairs Daughter of the Shakers: The Story of Eleanor Brooks Fairs By Johanne Grewell From the earliest time of my life, I knew that my mother was brought up by the Shakers. When I was pre-school age she gave talks during the day, and I went with her. While giving her talks, she showed the cape she wore while with the Shakers, her boxes, and her rocker. These were things that were part of our home. In addition, Eldress Anna Case’s picture was a part of her “family picture gallery.” We used the Shaker boxes for sewing and embroidery floss. I use them as sit about; however, Mom — being brought up by the Shakers — used each of them. For her they were utilitarian items. Figure 1 is titled “Eldress Anna and Her Girls.” My mother is in the front row, center; my Auntie Sue is in the second row to the right of Fig. 1.Eldress Anna and Her Girls (Richard Brooker Collection, CSC, Hamilton College) 187 Published by Hamilton Digital Commons, 2009 1 American Communal Societies Quarterly, Vol.