Download File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Operational Details Finalized As Debate Nears by Kate Gibson Ing All That Is Necessary to Host the Debate During the Daytime on Oct

arts & entertainment perspectives sports Harpist Yolanda Learning to fly: Bielek, Bergman Kondonssis and flutist A novice skydiver bring national Eugenia Zuckerman kick takes flight for the titles to Wake off Secrest Series first time Page B1 Page B5 Page A9 Press Box: 40ers Owens a picture of arrogance Old Gold and Black Page B1 thursday, september 28, 2000 “covers the campus like the magnolias” volume 84, no. 5 Operational details finalized as debate nears By Kate Gibson ing all that is necessary to host the debate during the daytime on Oct. 11, and the The Deacon Shop will be selling Presi- Old Gold and Black Reporter at Wake Forest,” said Sandra Boyette, “Our goal has been to reduce northern half will close at mid-day on the dential debate merchandise from 8:30 the vice president for university advance- inconvenience to the university same date to reopen only after the debate a.m. until after the debate, and the Sundry Last spring, the university began prepa- ment. has finished and the candidates have left Shop will continue its usual business rations for the Presidential Debate. Their From 10 p.m. Oct. 8 until noon on community as much as possible, the campus. hours. plans are now nearly Oct. 12, students and faculty must pres- while providing all that is necessary To begin its renovation into a debate The debate will also affect buildings sur- complete. ent their university identification card to to host the debate at Wake Forest.” hall, Wait Chapel will close at 5 p.m. rounding Wait Chapel. -

Myth and Memory: the Legacy of the John Hancock House

MYTH AND MEMORY: THE LEGACY OF THE JOHN HANCOCK HOUSE by Rebecca J. Bertrand A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in American Material Culture Spring 2010 Copyright 2010 Rebecca J. Bertrand All Rights Reserved MYTH AND MEMORY: THE LEGACY OF THE JOHN HANCOCK HOUSE by Rebecca J. Bertrand Approved: __________________________________________________________ Brock Jobe, M.A. Professor in charge of thesis on behalf of the Advisory Committee Approved: __________________________________________________________ J. Ritchie Garrison, Ph.D. Director of the Winterthur Program in American Material Culture Approved: __________________________________________________________ George H. Watson, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Approved: __________________________________________________________ Debra Hess Norris, M.S. Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Every Massachusetts schoolchild walks Boston’s Freedom Trail and learns the story of the Hancock house. Its demolition served as a rallying cry for early preservationists and students of historic preservation study its importance. Having been both a Massachusetts schoolchild and student of historic preservation, this project has inspired and challenged me for the past nine months. To begin, I must thank those who came before me who studied the objects and legacy of the Hancock house. I am greatly indebted to the research efforts of Henry Ayling Phillips (1852- 1926) and Harriette Merrifield Forbes (1856-1951). Their research notes, at the American Antiquarian Society in Worcester, Massachusetts served as the launching point for this project. This thesis would not have been possible without the assistance and guidance of my thesis adviser, Brock Jobe. -

Reston, a Planned Community in Fairfax County, Virginia Reconnaissance Survey of Selected Individual Historic Resources and Eight Potential Historic Districts

Reston, A Planned Community in Fairfax County, Virginia Reconnaissance Survey of Selected Individual Historic Resources and Eight Potential Historic Districts PREPARED FOR: Virginia Department of Historic Resources AND Fairfax County PREPARED BY: Hanbury Preservation Consulting AND William & Mary Center for Archaeological Research Reston, A Planned Community in Fairfax County, Virginia Reconnaissance Survey of Selected Individual Historic Resources and Eight Potential Historic Districts W&MCAR Project No. 19-16 PREPARED FOR: Virginia Department of Historic Resources 2801 Kensington Avenue Richmond, Virginia 23221 (804) 367-2323 AND Fairfax County Department of Planning and Development 12055 Government Center Parkway Fairfax, VA 22035 (702) 324-1380 PREPARED BY: Hanbury Preservation Consulting P.O. Box 6049 Raleigh, NC 27628 (919) 828-1905 AND William & Mary Center for Archaeological Research P.O. Box 8795 Williamsburg, Virginia 23187-8795 (757) 221-2580 AUTHORS: Mary Ruffin Hanbury David W. Lewes FEBRUARY 8, 2021 CONTENTS Figures .......................................................................................................................................ii Tables ........................................................................................................................................ v Acknowledgments ....................................................................................................................... v 1: Introduction ..............................................................................................................................1 -

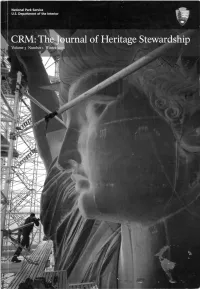

CRM: the Journal of Heritage Stewardship Volume 3 Number I Winter 2006 Editorial Board Contributing Editors

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior CRM: The Journal of Heritage Stewardship Volume 3 Number i Winter 2006 Editorial Board Contributing Editors David G. Anderson, Ph.D. Megan Brown Department of Anthropology, Historic Preservation Grants, University of Tennessee National Park Service Gordon W. Fulton Timothy M. Davis, Ph.D. National Park Service National Historic Sites Park Historic Structures and U.S. Department of the Interior Directorate, Parks Canada Cultural Landscapes, National Park Service Cultural Resources Art Gomez, Ph.D. Intermountain Regional Elaine Jackson-Retondo, Gale A. Norton Office, National Park Service Ph.D. Secretary of the Interior Pacific West Regional Office, Michael Holleran, Ph.D. National Park Service Fran P. Mainella Department of Planning and Director, National Park Design, University of J. Lawrence Lee, Ph.D., P.E. Service Colorado, Denver Heritage Documentation Programs, Janet Snyder Matthews, Elizabeth A. Lyon, Ph.D. National Park Service Ph.D. Independent Scholar; Former Associate Director, State Historic Preservation Barbara J. Little, Ph.D. Cultural Resources Officer, Georgia Archeological Assistance Programs, Frank G. Matero, Ph.D. National Park Service Historic Preservation CRM: The Journal of Program, University of David Louter, Ph.D. Heritage Stewardship Pennsylvania Pacific West Regional Office, National Park Service Winter 2006 Moises Rosas Silva, Ph.D. ISSN 1068-4999 Instutito Nacional de Chad Randl Antropologia e Historia, Heritage Preservation Sue Waldron Mexico Service, Publisher National Park Service Jim W Steely Dennis | Konetzka | Design SWCA Environmental Daniel J. Vivian Group, LLC Consultants, Phoenix, National Register of Historic Design Arizona Places/National Historic Landmarks, Diane Vogt-O'Connor National Park Service National Archives and Staff Records Administration Antoinette J. -

A Brief Survey of the Architectural History of the Old State House, Boston, Massachusetts1

A Brief Survey of the Architectural History of the Old State House, Boston, Massachusetts1 SARA B. CHASE* ven before they built their first governmental bodies. The Royal Governor structure to house a merchants ’ ex- and his Council met in a chamber at the east E change and government meeting end of the second floor, while the General hall, the early settlers of Boston had Assembly of the Province, with representa- selected a site near Long Wharf for a tives from each town, met in a larger marketplace. Early in 1658 they built there chamber in the middle of the second floor. a medieval half-timbered Town House. At the west end of the second floor was a That building, the first Boston Town smaller chamber where both the superior House, burned to the ground in October, and the inferior courts of Suffolk County 1711. It was replaced by a brick building, held sessions. Until 1742 when they moved erected on the same site. This building, like to Faneuil Hall, Bostons’ Selectmen met in the earlier Town House, had a “merchants’ the middle (or representatives)’ chamber walk” on the first floor and meeting cham- and used a few finished rooms on the third bers for the various colonial government floor for committee meetings. bodies on the second floor. The first floor served primarily as a mer- Although this new building was called by chants ’ exchange, as it had in the previous various names--the Court House, the Town House. Situated less than one- Second Town House, the Province House quarter mile from Long Wharf, the Old (not to be confused with the Peter Sergeant State House was a convenient first stop for House which was also called by that name) ships ’ captains when they landed in Bos- --the name most frequently used in refer- ton. -

Financial District.04

t Christopher Clinton St Columbus C t o S Waterfront t th n or w membershipapplication S g N Park t r e e rf s ha s g W s r Lon C e e 2 a M h I would like to: 0 v t m S am a 0 o e h A at 2 h t C R r h Government n S n c join renew be on email list o a o i l l h Aquarium A t w m Center s ܙ ܙ ܙ k R C a C o ornhil A t l l n S n t B k o e a I r 4 k a t C n n l w n o r s t u d e a corporate levels [benefits on back] t r t t F r i n W i r t S c S a t 6 y a al B tr t n © S A e e l C t S 5 racewalker $5000 State Sta K START v i 3 t ܙ l e b t t e k S y Mil o r strider $2500 e v t F S u r 7 ܙ A END C 2 S al o a l 1 r t t e l o n C u t e stroller $1000 e a n C q S s g m Q ܙ H t t S r n S a S e y u 8 ambler $300 t o Pl n i s t a by k e e il t l l s g K t i I ܙ 20 C g r k n t n i ha S m d y M P e c n r P S x S ia i h E e o t i t t r t o A S s t a l h e n l s t L W a individual/family levels [benefits on back] s n P t u s di e o S W t In a s B u as a o e e E i aw ro C o ll m 19 v H a S W d n c e e H t sustaining $500—$5000 S t r B t T t l D Water o ܙ a w c S P tte Ro 9 i supporter $100—$499 t 17 ry S - n n Sc 18 m r ܙ o a ho St ol a t m B m t St O n o r friend $65 e p S ing l c s r s Spr iv h w - a n i ܙ a T e e o h c La r to S t i rt P n S S D dual/family $50 h C in ro e t l S v v t t J y l ܙ n t in 16 a e o S d l B r ce k W n $30 o r C il e individual o P t t W a t m Milk S M ܙ f i ie C s 15 P ld St c o t h H S t e S Hig n o a a t n S F 10 n additional contribution $___________ D m g r in e l l i y r l a e k B t S o d le e n n v t a e s r n P o F w s F l r e i r a n a name a o s l n H F h ic l k h S t s l i t r P i 11 t n H O s u e ll a organization w ’ M a le S li S v d H y t e Pl n W t r n in S s address ter St t o a St Downtown 13 12 t s n e Crossing S o P no o o l t w P S B t P e S y l 14 a s u e r day phone m l B l w u G S | o m s B a s r t e H e t id B r y S t l eve. -

25 Indian Road, 4F | New York, NY 10034 (212) 942-2743 Cell (917) 689-4139

25 Indian Road, 4F | New York, NY 10034 (212) 942-2743 Cell (917) 689-4139 SIMON SUROWICZ [email protected] TEACHING Adjunct Professor, Columbia University, The Graduate School of Journalism 2010 Adjunct, New York University, School of Continuing & Professional Studies 2008 ● Digital Broadcast Journalism ● Investigative Journalism MULTIMEDIA Senior Multimedia Producer, ABC News.com 2006 - 2009 ● Created and launched “The Blotter,” ABC News’ award-winning Investigative Team's Web site. ● Managing editor responsible for overall day-to-day editorial oversight. ● Liaison with the Web development team on functional specifications and layout implementations. ● Developed distribution channels to deliver original “Blotter” content across all ABC News platforms. ● Managed a small team of graphic artists, video editors, IT specialists and content management engineers. ● Broke several major news stories, including the Congressman Mark Foley sex scandal which changed the political landscape in Congress (12 million impressions for a single story, the highest ever at ABCNews.com). ● Oversaw substantial growth – routinely reached and surpassed monthly metrics goals. ● The Blotter’s innovative concept and unique design was widely emulated at ABCNews.com. Senior Producer, Brian Ross Investigates Webcasts 2006 – 2009 www.simonsurowicz.com ● Produced weekly Webcasts, featuring top experts examining the major investigative stories of the week. (*partial list) Interrogation Techniques: Waterboarding A Sting Gone Bad: To Catch a Predator Inside a Taliban ‘Commencement’ To Heimlich or not to Heimlich? Covert ‘Black’ Operation in Iran TELEVISION Producer, ABC News 1995 – 2006 ● Produced broadcast segments for all ABC News platforms, including: "20/20", "Primetime Live", "World News Tonight", "Nightline" and "Good Morning America". (*The following is a partial list) ● “The Great Diamond Heist” Produced a one-hour exclusive ABC News PrimeTime Special on the largest diamond heist in history, now being turned into a movie by Paramount. -

Nailing an Exclusive Interview in Prime Time

The Business of Getting “The Get”: Nailing an Exclusive Interview in Prime Time by Connie Chung The Joan Shorenstein Center I PRESS POLITICS Discussion Paper D-28 April 1998 IIPUBLIC POLICY Harvard University John F. Kennedy School of Government The Business of Getting “The Get” Nailing an Exclusive Interview in Prime Time by Connie Chung Discussion Paper D-28 April 1998 INTRODUCTION In “The Business of Getting ‘The Get’,” TV to recover a sense of lost balance and integrity news veteran Connie Chung has given us a dra- that appears to trouble as many news profes- matic—and powerfully informative—insider’s sionals as it does, and, to judge by polls, the account of a driving, indeed sometimes defining, American news audience. force in modern television news: the celebrity One may agree or disagree with all or part interview. of her conclusion; what is not disputable is that The celebrity may be well established or Chung has provided us in this paper with a an overnight sensation; the distinction barely nuanced and provocatively insightful view into matters in the relentless hunger of a Nielsen- the world of journalism at the end of the 20th driven industry that many charge has too often century, and one of the main pressures which in recent years crossed over the line between drive it as a commercial medium, whether print “news” and “entertainment.” or broadcast. One may lament the world it Chung focuses her study on how, in early reveals; one may appreciate the frankness with 1997, retired Army Sergeant Major Brenda which it is portrayed; one may embrace or reject Hoster came to accuse the Army’s top enlisted the conclusions and recommendations Chung man, Sergeant Major Gene McKinney—and the has given us. -

NATAS Supplement.Qxd

A SPECIAL SUPPLEMENT TO BROADCASTING & CABLE AND MULTICHANNEL NEWS The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences at 50 years,0 A golden past with A platinum future marriott marquis | new york october 20-21, 2005 5 THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES Greetings From The President Executive Committee Dennis Swanson Peter O. Price Malachy Wienges Chairman of the Board President & CEO Treasurer Dear Colleagues, Janice Selinger Herb Granath Darryl Cohen As we look backwards to our founding and forward to our future, it is remarkable Secretary 1st Vice Chairman 2nd Vice Chairman how the legacy of our founders survives the decades. As we pause to read who Harold Crump Linda Giannecchini Ibra Morales composed Ed Sullivan’s “Committee of 100” which established the Academy in 1955, Chairman’s Chairman’s Chairman’s the names resonate with not just television personalities but prominent professionals Representative Representative Representative from theatre, film, radio, magazines and newspapers. Perhaps convergence was then Stanley S. Hubbard simply known as collaboration. Past Chairman of the Board The television art form was and is a work in progress, as words and pictures morph into new images, re-shaped by new technologies. The new, new thing in 1955 was television. But television in those times was something of an appliance—a box Board of Trustees in the living room. Families circled the wagons in front of that electronic fireplace Bill Becker Robert Gardner Paul Noble where Americans gathered nightly to hear pundits deliver the news or celebrities, fresh from vaudeville and Betsy Behrens Linda Giannecchini David Ratzlaff Mary Brenneman Alison Gibson Jerry Romano radio, entertain the family. -

Hclassification

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ I NAME HISTORIC Massachusetts State House AND/OR COMMON Massachusetts State House I LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Beacon Hill —NOT FOR PUBiJCATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Boston . VICINITY OF 8 th STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 25 Suffolk 025 HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE ...DISTRICT X.PUBLIC AOCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM -XBUILDING(S) _PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL ...PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —.WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL — PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS _OBJECT _IN PROCESS XYES: RESTRICTED -KGOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC ..BEING CONSIDERED — YES UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL — TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Commonweath of Massachusetts STREETS NUMBER Beacon Street CITY" TOWN STATE VICINITY OF Massachusetts (LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC Suffolk County Registry of Deeds STREETS NUMBER Somerset Street CITY. TOWN STATE Boston Massachusetts REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLELE Historic American Buildings Survey (Gates and Steps, 10 sheets, 6 photos) DATE 1938,1941 X FEDERAL —.STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Library of Congress/Annex Division of Prints and Photographs CITY. TOWN STATE Washington D.C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED _UNALTERED ^ORIGINAL SITE —GOOD _RUINS FALTERED _MOVED DATE_____ —FAIR —UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The following description from the Columbian Centinel, January 10, 1798 is reproduced in Harold Kinken's The Architecture of Charles Bulfinch, The New State-House is an oblong building, 173 feet front, and 61 deep, it consists externally of a basement story, 20 feet high, and a principal story 30 feet. -

A LONG ROAD to ABOLITIONISM: BENJAMIN FRANKLIN'stransformation on SLAVERY a University Thesis Presented

A LONG ROAD TO ABOLITIONISM: BENJAMIN FRANKLIN’STRANSFORMATION ON SLAVERY ___________________ A University Thesis Presented to the Faculty of of California State University, East Bay ___________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in History ___________________ By Gregory McClay September 2017 A LONG ROAD TO ABOLITIONISM: BENJAMIN FRANKLIN'S TRANSFORMATION ON SLAVERY By Gregory McClay Approved: Date: ..23 ~..(- ..2<> t""J ;.3 ~ ~11- ii Scanned by CamScanner Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………1 Existing Research………………………………………………………………….5 Chapter 1: A Man of His Time (1706-1762)…………………………………………….12 American Slavery, Unfree Labor, and Franklin’s Youth………………………...12 Franklin’s Early Writings on Slavery, 1730-1750……………………………….17 Franklin and Slavery, 1751-1762………………………………………………...23 Summary………………………………………………………………………....44 Chapter 2: Education and Natural Equality (1763-1771)………………………………..45 John Waring and the Transformation of 1763…………………………………...45 Franklin’s Ideas on Race and Slavery, 1764-1771……………………………....49 The Bray Associates and the Schools for Black Education……………………...60 The Georgia Assembly…………………………………………………………...63 Summary…………………………………………………………………………68 Chapter 3: An Abolitionist with Conflicting Priorities (1772-1786)…………………….70 The Conversion of 1772…………….……………………………………………72 Somerset v. Stewart………………………………………………………………75 Franklin’s Correspondence, 1773-1786………………………………………….79 Franklin’s Writings during the War Years, 1776-1786………………………….87 Montague and Mark -

Essays of an Information Scientist, Vol:5, P.703,1981-82 Current

3. -------------0. So you wanted more review articles- ISI’s new Index to Scientific Reviews (ZSR) will help you find them. Essays of an information scientist. Philadelphia: IS1 Press, 1977. Vol. 2. p. 170-l. (Reprinted from: Current Contents (44):5-6, 30 October 1974.) 4. --------------. Why don’t we have science reviews? Essays of an information scientist. Philadelphia: IS1 Press, 1977. Vol. 2. p. 175-6. (Reprinted from: Current Contents (46):5-6, 13 November 1974.) 5. --1.1..I- Proposal for a new profession: scientific reviewer. Essays of an information scientist. Philadelphia: IS1 Press, 1980. Vol. 3. p. 84-7. (Reprinted from: Current Contents (14):5-8, 4 April 1977.) Benjamin Franklin- 6. ..I. -.I-- . ..- The NAS James Murray Luck Award for Excellence in Scientific Reviewing: G. Alan Robison receives the first award for his work on cyclic AMP. Essays of an information Philadelphia’s Scientist Extraordinaire scientist. Philadelphia: IS1 Press, 1981. Vol. 4. p. 127-31. (Reprinted from: Current Contents (18):5-g, 30 April 1979.) 7, .I.-.- . --.- The 1980 NAS James Murray Luck Award for Excellence in Scientific Reviewing: Conyers Herring receives second award for his work in solid-state physics. Number 40 October 4, 1982 Essays of an information scientist. Philadelphia: IS1 Press, 1981. Vol. 4. p. 512-4. (Reprinted from: Current Contents (25):5-7, 23 June 1980.) Earlier this year I invited Current Con- ness. Two years later, he was appren- 8. ..- . - . ..- The 1981 NAS James Murray Luck Award for Excellence in Scientific Reviewing: tents@ (CC@) readers to visit Philadel- ticed to his brother James, a printer.