Rose Vol 8 Nr 2.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pacifica Journal #33 2008(1)

Pacifica Journal A bi-annual newsletter published by the Anthroposophical Society in Hawai'i Number 33, 2008-1 China: A Phoenix from the Ashes physically, soul-wise and spiritually in a country that is in the process of re-inventing itself in an amazingly intense way. Susan Howard, Amherst, Massachusetts, USA Now, post-earthquake, we are deeply concerned with the situation in Szechuan Province. Two weeks ago we visited the city of Dujiangyan, 60 km west of Chengdu, en route On May 13th a powerful and devastating earthquake struck to hiking among the Taoist temples at Qincheng Mountain. in Szechuan Province in the area around Chengdu, home of Dujiangyan is one of two epicenters of the earthquake, and the first Waldorf School in China. I am writing to you today we are struggling to bring together two sets of images - one to ask for your support in the aftermath of the earthquake for the lovely, pleasant green city at the edge of the mountains the teachers, parents and children of the Chengdu Waldorf close to the Tibet border, away from the pollution of Chengdu, School. and the other the site of collapsed hospitals, factories and a I returned from China on the day of the earthquake after middle school where many children perished - children who, teaching in the Waldorf kindergarten training program hosted with the One Child Policy, were their parents' beloved only by the Chengdu Waldorf School. My husband Michael and I child and who now are gone. We can hardly bear to think of taught the nearly 100 kindergarten teachers from all over China the grieving taking place now, and the chaos of homelessness - mostly from Chengdu, Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Hong that has ensued. -

Sustainability Report 2011

Profile of SEKEM’s Report on Sustainable Development 2011 The reporting period of the Report on Sustainable well, the hard facts in the Performance Report will update Development 2011 is January to December 2011 and thus them on the newest developments. continues the Sustainable Development story of the 2010 If not otherwise stated, the scope includes all SEKEM report that had been published at the end of August 2011. companies as of page 18-19, excluding SEKEM Europe SEKEM uses the report for communicating on all four and Predators. Where stated, the SEKEM Development dimensions of the Sustainable Development Flower including Foundation was included into the data. The basis for this the financial statement. report is mainly deduced from certified management and In this fifth Report on Sustainable Development, some changes quality management systems. We aimed to ensure that the were made regarding the structure. We have separated the data and information provided in this report is as accurate descriptive part of our approach to sustainable development as possible. Wherever data is based on estimations and/or from the annual hard facts. This was done to make the other limitations apply, this is indicated. In cases of significant information more accessible for all readers. For those just changes, these are described directly in the context. getting to know what SEKEM is all about, reading the first part A detailed index of the information requested by the GRI will be a good start. For those who already know SEKEM quite 3 and the Communication on Progress (CoP) of the UN Global Compact is provided at page 84 to 92. -

COMPLETE BACKLIST and ORDER FORM January 2013 Backlist By

COMPLETE BACKLIST and ORDER FORM January 2013 Oliphant, Laurence and Meyer, T.H. (Ed) When a Stone Begins to Roll: Notes Backlist by of an Adventurer, Diplomat & Mystic: Contents Extracts from Episodes in a Life of Backlist by subject subject Adventure 2011 | 204 x 126 mm | 160pp | LIN Non-Fiction 978-158420-091-8 | paperback | £9.99 Mind Body Spirit 1 NON-FICTION Ouspensky, P. D. Holistic Health 2 Strange Life of Ivan Osokin: A Novel MIND BODY SPIRIT 2002 | 220 x 140 mm | 192pp | LIN Organics, Biodynamics 3 978-158420-005-5 | paperback | £12.99 Christian Spirituality 3 Allen, Jim Bible 4 Atlantis: Lost Kingdom of the Andes Pogacnik, Marko 2009 | 240 x 208 mm | 100 colour illustrations | 240pp | FLO Gaia’s Quantum Leap: A Guide to Living World Spirituality 5 978-086315-697-7 | paperback | £16.99 through the Coming Earth Changes Celtic Spirituality 5 2011 | 215 x 234 mm | 228pp | LIN Baum, John 978-158420-089-5 | paperback | £12.99 Science & Spirituality 5 When Death Enters Life Steiner-Waldorf Education 7 2003 | 216 x 138 mm | 144pp | FLO Pogacnik, Marko and Pogacnik, Ana Steiner-Waldorf 978-086315-389-1 | paperback | £9.99 How Wide the Heart: The Roots of Peace Drake, Stanley and van Breda, Peter (Ed) in Palestine and Israel Teacher Resources 7 2007 | 256 x 134 mm | 60 b/w photographs | 216pp | LIN Special Needs Education 8 Though You Die: Death and 978-158420-039-0 | paperback | £14.99 Life Beyond Death Karl König Archive 8 2002 | 198 x 128 mm | 4th ed | 128pp | FLO Pogacnik, Marko Art & Architecture 8 978-086315-369-3 | paperback | £6.99 Sacred Geography: Geomancy: Language & Literature 8 Elsaesser-Valarino, Evelyn Co-creating the Earth Cosmos 2008 | 234 x 156 mm | 194 b/w illustrations | 248pp | LIN Philosophy 8 Talking with Angel: About Illness, 978-158420-054-3 | paperback | £14.99 Child Health & Development 13 Death and Survival 2005 | 216 x 138 mm | 208pp | FLO Pogacnik, Marko Children’s Books 978-086315-492-8 | paperback | £9.99 Turned Upside Down: A Workbook Picture & Board Books 14 Finser, Siegfried E. -

Parigi E Il Quinto Vangelo

N.57 - 2020 ANTROPOSOFIA OGGI € 5,50 ParigiParigi ee ilil QuintoQuinto VangeloVangelo I disegni spontanei dei bambini POSTE ITALIANE S.P.A. - SPEDIZIONE IN ABBONAMENTO POSTALE AUT. N.0736 PERIODICO ROC DL.353/2003 (CONV.IN L.27/02/2004 N.46) ART.1 COMM1 I, DCB MILANO L.27/02/2004 N.46) ART.1 N.0736 PERIODICO ROC DL.353/2003 (CONV.IN AUT. - SPEDIZIONE IN ABBONAMENTO POSTALE S.P.A. POSTE ITALIANE Il calore dentro e fuori di noi Dalla Natura soluzioni efficaci per la salute e il benesserre di tutta la famiglia Rimedi sviluppati secondo i principi dell’’AAntroposofia, dal 19355 Per inffoormazioni: La cosmesi Dr. Hauschka è prodotta da wwww..drr..hauschka.com WWAALA ITTAALIA [email protected] WALA Heilmittel GmbH, Germania wwww..wala.it Via Fara, 28 - 20124 Milano [email protected] EDITORIALE Eravamo pronti per andare in stampa quando si è diffusa la notizia che l’Italia si trovava sfortunatamente in prima linea nella lotta al Coronavirus. È inquie- tante notare come si possano scatenare emozioni in una dimensione fino ad ora impensabile. Anche i medici sono più o meno concordi nell’affermare che si tratti di una sorta di influenza come ne abbiamo ogni anno e che spesso è causa di tanti problemi soprattutto per le persone anziane. Come siamo arrivati, quindi, a dare a questo virus le dimensioni di una pandemia di gravità tale che rischia di essere ingestibile, in quanto le strutture sanitarie risulterebbero inadeguate ma soprattutto sarebbero insufficienti? Fa paura questa grande fragilità della nostra società che potrebbe facilmente diventare una forza ma- nipolabile da influenze negative. -

General Anthroposophical Society Annual Report 2002

General Anthroposophical Society Annual Report 2002 Annual Report 2002 Contents General Anthroposophical Society Theme of the Year for 2003/04: Metamorphosis of Intelligence and Co-responsibility for Current Affairs ................. 3 General Anthroposophical Society: The Impulse of the 1923/24 Christmas Conference in the Year 2002 ................... 4 School of Spiritual Science The Sections General Anthroposophical Section ..................................................................................................................................................... 5 Section for Mathematics and Astronomy .......................................................................................................................................... 7 Medical Section ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 7 Natural Science Section and Agriculture Department .................................................................................................................... 9 Pedagogical Section ............................................................................................................................................................................... 11 Art Section .............................................................................................................................................................................................. 12 Section for the Spiritual -

Goldenblade 2002.Pdf

RUDOLF STEINER LIBRARY VYDZ023789 T H E G O L D E N B L A D E KINDLING SPIRIT 2002 54th ISSUE RUDOLF STEINER LIBRARY 65 FERN HILL RD GHENT NY 12075 KINDLING SPIRIT Edited by William Forward, Simon Blaxland-de Lange and Warren Ashe The Golden Blade Anthroposophy springs from the work and teaching of Rudolf Steiner. He described it as a path of knowledge, to guide the spiritual in the human being to the spiritual in the universe. The aim of this annual journal is to bring the outlook of anthroposophy to bear on questions and activities relevant to the present, in a way which may have lasting value. It was founded in 1949 by Charles Davy and Arnold Freeman, who were its first editors. The title derives from an old Persian legend, according to which King Jamshid received from his god, Ahura Mazda, a golden blade with which to fulfil his mission on earth. It carried the heavenly forces of light into the darkness of earthly substance, thus allowing its transformation. The legend points to the pos sibility that humanity, through wise and compassionate work with the earth, can one day regain on a new level what was lost when the Age of Gold was supplanted by those of Silver, Bronze and Iron. Technology could serve this aim; instead of endan gering our plantet's life, it could help to make the earth a new sun. Contents First published in 2001 by The Golden Blade © 2001 The Golden Blade Editorial Notes 7 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without prior permission of The Human Being's Responsibility for the Evolution -

Goetheanum Content

General Anthroposophical Society 2005/2006 Goetheanum Content 3 Editorial The Anthroposophical Society 4 Theme of the year 2006/2007 4 Anthroposophical Society in Romania 5 Membership development School of Spiritual Science 6 General Anthroposophical Section 7 Natural Science Section 7 Section for Mathematics and Astronomy 8 Medical Section 8 Pedagogical Section 9 Section for the Art of Eurythmy, Speech, Drama and Music 9 Section for the Literary Arts and Humanities 9 Section for Agriculture 10 Youth Section 11 Section for the Social Sciences 11 Art Section The Goetheanum 12 Eurythmy Ensemble at the Goetheanum 12 Developments at the Goetheanum 13 Financial report 2005/2006 16 Contacts and addresses Publishing details Publisher: General Anthroposophical Society. Text and interviews: Wolfgang Held (General Anthroposophical Section: Bodo v. Plato, Robin Schmidt, Heinz Zimmermann; Section for Mathematics and Astronomy: Oliver Conradt; Section for the Literary Arts and Humanities: Martina Maria Sam; Financial report 2005/06: Cornelius Pietzner). Editorial: Wolfgang Held, Cornelius Pietzner, Bodo v. Plato. Layout: Christian Peter, Parzifal Verlag (CH). Printer: Kooperative Dürnau (DE). Editorial Editorial Dear members and friends of the Anthroposophical Society, The Anthroposophical Society is growing. By that we do not primarily mean the membership numbers which have remained largely steady in recent years – with the exception of countries outside Europe – but rather the char- acter of the Society. It is the human diversity, the spiritual yearnings and abil- ities of the members which have grown in dimension. It is because everyone who is active in the Anthroposophical Society today contributes their expe- rience and opportunities from varied cultural perspectives and different parts of the world to the Anthroposophical Society so that the life and way of work- ing within the Society is becoming more open and diverse. -

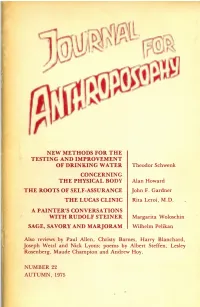

Journal Fnthpsy N Ew Methods for the Testing

JOURNAL FORANTHROPOSOPHYNEW METHODS FOR THE TESTING AND IMPROVEMENT OF DRINKING WATER Theodor Schwenk CONCERNING THE PHYSICAL BODY Alan Howard THE ROOTS OF SELF-ASSURANCE John F. Gardner THE LUCAS CLINIC Rita Leroi, M.D. A PAINTER S CONVERSATIONS WITH RUDOLF STEINER Margarita Woloschin SAGE, SAVORY AND MARJORAM Wilhelm Pelikan Also reviews by Paul Allen, Christy Barnes, Harry Blanchard, Joseph Wetzl and Nick Lyons; poems by Albert Steffen, Lesley Rosenberg, Maude Champion and Andrew Hoy. NUMBER 22 AUTUMN, 1975 Spiritual knowledge is the nourishment of the spirit. By withholding it, man lets his spirit starve and perish; thus enfeebled he grows powerless against processes in his physical and life bodies which gain the upper hand and overpower him. Rudolf Steiner Journal for Anthroposophy. Number 22, Autumn, 1975 © 1975 The Anthroposophical Society in America, Inc. New Methods for the Testing and Improvement of Drinking Water THEODOR SCHWENK Many of those who live in our great cities no longer drink the water from their faucets but prefer to buy expensive mineral water and bottled spring water. Whereas formerly it was taken for granted that people drew drinking water from a spring or well, where it begins its cycle, nowadays, for the most part, we must resort to treating polluted river water so as to make it chemically and bacterio- logically “acceptable.” This, however, ignores the fact that drinking water consists not only of the chemical element H2O — albeit with various salts and trace elements held in solution — but is actually a [Image: photograph]Pattern formed by drinking water of highest quality. 1 [Image: photograph]Pattern formed by a sample of drinkable quality from a Black Forest stream. -

Aqd`Sghmf Khfgs; @ Xnf` Enq Sgd Rdmrdr

PacificaA bi-annual newsletter published by the AnthroposophicalJournal Society in Hawai'i Number 25 2004 (1) Breathing Light: But parallel with the cultivation of an inner life, Rudolf Steiner also consistently emphasized another aspect to A Yoga for the Senses meditation, one directed not inward but outward into the sense world. On various occasions, he contrasted the path Arthur Zajonc, Amherst, Massachusetts, USA inward, into the soul, with the path outward into the sense world, terming them the “mystical” and “alchemical” paths Colors and sound are windows through which we can ascend respectively.3 Concerning the mystic path into one’s soul, he spiritually into the spirit world, and life also brings to us windows indicated how difficult it can be to know if one is free of the through which the spiritual world enters our physical world... Human deceptions caused by Lucifer and Ahriman.4 Try as we might beings will make important discoveries in the future in this respect. They to draw something from ourselves, it constantly suffers the will actually unite their moral-spiritual nature with the results of sense danger of being permeated with instincts. Steiner states it perception. An infinite deepening of the human soul can be foreseen in dramatically in his January 1924 lecture after the Christmas this domain.1 Foundation Stone meeting: “All that arises from within —Rudolf Steiner Between the physical, sense-perceptible world and the world of spirit a chasm yawns. It is no physical chasm, yet as we draw near to it, our inner experience is much like that we have when standing at the very edge of a cliff. -

Gesamtinhaltsverzeichnis 1947-1971 Zu "Mitteilungen Aus Der Anthroposophischen Arbeit in Deutschland"

Fünfundzwanzig Jahre Gesamtinhaltsverzeichnis 1947-1971 Mitteilungen aus der anthroposophischen Arbeit in Deutschland Gesamtüberblick über den Inhalt in den Jahren 1947-1971 Zusammengestellt von Herta Blume Nur für Mitglieder der Anthroposophischen Gesellschaft INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Seite Vorbemerkung Geleitwort III Die Redaktionen der Mitteilungen IV Motive aus dem Jahre 1923 V 1. Aufsätze - Erinnerungen - Zuschriften A. Nach Sachgebieten chronologisch geordnet Arbeit an der anthroposophischen Substanz 1 Erkenntnis- und Schulungs weg 6 Die Weihnachtstagung und der Grundstein 7 Gesellschaftsgestaltung - Gesellschaftsgeschichte 9 Völkerfragen, insbesondere Mittel- und Osteuropa 12 Die soziale Frage - Soziale Dreigliederung 14 Waldorfschul-Pädagogik 18 Medizin - Heilpädagogik 19 Naturwissenschaft - Technik 20 Ernährung - Landwirtschaft 22 Elementarwesen 23 Kalender - Ostertermin - kosmische Aspekte 24 Jahreslauf - Jahresfeste - Erzengel 25 Der Seelenkalender 27 Zum Spruchgut von Rudolf Steiner 27 Eurythmie - Sprache - Dichtung 29 Über die Leier 29 Bildende Kunst - Kunst im Allgemeinen 30 Die Mysteriendramen 31 Die Oberuferer Weihnachtsspiele 32 Über Marionettenspiele 32 Baukunst - Der Bau in Dornach 33 Die Persönlichkeit Rudolf Steiners, ihr Wesen und Wirken 35 Marie Steiner-von Sivers 38 Erinnerungen an Persönlichkeiten und Ereignisse 39 Biographisches und Autobiographisches 43 Seite Christian Rosenkreutz 44 Goethe 44 Gegnerfragen 45 Genußmittel - Zivilisationsschäden 46 Verschiedenes 47 B. Nach Autoren geordnet 49 Ir. Buchbesprechungen A. -

SEKEM Vision and Mission 2057 1977 – 2017 – 2057

SEKEM Vision and Mission 2057 1977 – 2017 – 2057 Building a Sustainable Community For Egypt and the World SEKEM Vision and Mission 2057 SEKEM Vision and Mission 2057 This document has been compiled by Helmy Abouleish with the support of Amina El Shamsy Christine Arlt Dalia Abdou Maximilian Abouleish-Boes Noha Hussein Thomas Abouleish Thoraya Seada and in consultation with the Members of the SEKEM Future Council Version N°: 15.6.18 This document was developed internally by the SEKEM Future Council and does not claim to be fully scientific. Moreover, it is not a definitive version but under constant development. SEKEM Holding Head Office: 3 Cairo Belbes Desert Road, El Salam, Egypt Tel.: (+20) 2 265 88 124/5 Mail: [email protected] P.O.Box 2834 El Horreya, 11361 Cairo, Egypt Fax: (+20) 2 265 88 123 Web: www.sekem.com “Concerning all acts of initiative and creation, there is one elementary truth, the ignorance of which kills countless ideas and splendid plans: that the moment one definitely commits one- self, then Providence moves too. All sorts of things occur to help one that would never other- wise have occurred. A whole stream of events issues from the decision, raising in one’s favour all manner of unforeseen incidents and meetings and material assistance, which no man could have dreamt would have come his way. I have learned a deep respect for one of Goethe’s couplets: Whatever you can do, or dream you can, begin it. Boldness has genius, power, and magic in it!” William Hutchinson Murray SEKEM Vision and Mission 2057 40 Years of Sustainable Development SEKEM1 Addressing Societal Challenges Egypt is facing many challenges: in regards to climate change, food insecurity, water scarcity, desertification, unemployment, migration, education and many more. -

SEKEM Report 2019

Sustainable Development since 1977 Report | 2019 When thinking becomes artistic it moves in images. The image of the four-foldness of life is a grand gesture, in which all components connect in a living motion. The great whole - the all-encompassing idea – embraces and forms the individual manifestations which are embedded like organs in a great organism. SEKEM developed into its current form through organic growth. Dr. Ibrahim Abouleish Dr. Ibrahim Abouleish 1937-2017 Table of Contents CEO Statement 05 Fact Sheet 06 SEKEM Consolidated Ratios 07 Sustainability Highlights 08 About SEKEM 13 SEKEM Holding Financial Statement 29 SEKEM’s Holistic Development Approach 31 SEKEM Vision Goals 32 SEKEM Vision Goal Priorities for 2019 32 SEKEM Vision Goal 13: Economy of Love 32 SEKEM Vision Goal 01: Holistic Education to unfold potential 34 Other SEKEM Vision Goals along the Four Dimensions of SEKEM’s Sustainability Flower 37 Cultural Life 37 SVG 2: Integral University Model 37 SVG 3: Holistic Research 39 SVG 4: Integrative Medicine 41 SVG 5: New Culture 43 Ecological Life 45 SVG 6: 100% Organic 46 SVG 7: Self-sustaining Water Management 50 SVG 8: 100% Renewable Energies 51 SVG 9: Stabilized Biodiversity 53 SVG 10: Active Climate Mitigation 54 SVG 11: Zero Waste 56 Economic Life 58 SVG 12: Circular Economy 58 SVG 14: Ethical Banking 59 SVG 15: Offer of Biodynamic Products 60 SVG 16: Transparent Trading 61 4.2.4. Societal Life 63 SVG 17: Social Transformation 63 SVG 18: Future-oriented Governance 65 Annex 66 SEKEM Sustainability Indicators Table 66 Auditor’s Statement 76 Index of Abbreviations 78 SEKEM Report – 2019 Dear Readers, Since the publishing of SEKEM’s Vision for 2057, we have been setting two vision goals to focus on every year.