Berlin Koreans and Pictured Koreans [Reading Sample]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notizen 1312.Indd

27 Feature II Franz Eckert und „seine“ Nationalhymnen. Eine Einführung1 von Prof. Dr. Hermann Gottschewski und Prof. Dr. Kyungboon Lee Der preußische Militärmusiker Franz Eckert2, geboren 1852, wurde 1879 als Musiklehrer nach Japan berufen, wo er kurz vor seinem 27. Geburtstag eintraf. Er war dort bis 1899 in ver- schiedenen Positionen tätig, insbesondere als musikalischer Mentor der Marinekapelle. Für mehrere Jahre unterrichtete er auch an der To- yama Armeeschule, außerdem an der Musik- akademie Tokyo und nicht zuletzt an der Musi- kabteilung des Kaiserhofes. In die Zeit seines Wirkens in Japan fällt der Japanisch-Chinesi- sche Krieg, in dem die Militärmusik einen sehr großen Einfluss auf den öffentlichen Musikge- schmack gewann. Von der musikhistorischen Forschung wird dieser Einfluss als einer der wesentlichen Faktoren für die Durchsetzung der westlichen Musik in der modernen japani- schen Musikkultur gesehen. Abb. 1: Aus dem Nachruf Eckert von 1926, in: Mitteilungen der Deutschen Gesellschaft 1899 kehrte Eckert zunächst nach Deutschland für Natur- und Völkerkunde Ostasiens, zurück, aber nach einer kurzen Interimszeit in Band XXI. Dieser Nachruf fehlt in dem Berlin erhielt er einen Ruf an den koreanischen Nachdruck der Mitteilungen von 1965. 1 Dieses Feature geht auf 2 Vorträge zurück, die von den Autoren am 18.9.2013 in der OAG gehalten wurden. 2 Die bisher eingehendste Forschung zu Eckerts Biographie ist von Nakamura Rihei: Yōgaku Dōnyūsha no Kiseki ‒ Nihon Kindai Yōgaku-shi Josetsu (Die Spuren der Einführer westlicher Musik ‒ Eine Einführung in die Geschichte westlicher Musik in der japanischen Moderne), Tōsui Shobō 1993, S. 235- 363. Die grundlegendste Forschung zu Eckerts koreanischen Jahren ist von Namgung Yoyŏl: Gaehwagi ŭi Hanguk-ŭmak ‒ Franz Eckert rŭl jungsim-ŭro (Die koreanische Musik der Aufklärungszeit, insbesondere über Franz Eckert), Seoul: Segwang Ŭmak Chulpanja, 1987. -

Transformation of the Dualistic International Order Into the Modern Treaty System in the Sino-Korean Relationship

International Journal of Korean History (Vol.15 No.2, Aug.2010) 97 G Transformation of the Dualistic International Order into the Modern Treaty System in the Sino-Korean Relationship Song Kue-jin* IntroductionG G Whether in the regional or global scale, the international order can be defined as a unique system within which international issues develop and the diplomatic relations are preserved within confined time periods. The one who has leadership in such international order is, in actuality, the superpowers regardless of the rationale for their leading positions, and the orderliness of the system is determined by their political and economic prowess.1 The power that led East Asia in the pre-modern era was China. The pre- modern East Asian regional order is described as the tribute system. The tribute system is built on the premise of installation, so it was important that China designate and proclaim another nation as a tributary state. The system was not necessarily a one-way imposition; it is possible to view the system built on mutual consent as the tributary state could benefit from China’s support and preserve the domestic order at times of political instability to person in power. Modern capitalism challenged and undermined the East Asian tribute GGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGGG * HK Research Professor, ARI, Korea University 98 Transformation of the Dualistic International Order into the ~ system led by China, and the East Asian international relations became a modern system based on treaties. The Western powers brought the former tributary states of China into the outer realm of the global capitalistic system. With the arrival of Western imperialistic powers, the East Asian regional order faced an inevitable transformation. -

Kommunismus-Kapitalismus Als Ursache Nationaler Teilung

Kommunismus-Kapitalismus als Ursache nationaler Teilung Das Bild des geteilten Koreas in der deutschen und des geteilten Deutschlands in der koreanischen Literatur (seit den 50er Jahren) Der Fakultät IV – Geschichte der Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg zur Erlangung des Grades eines Doktors der Philosophie(Dr. Phil) vorgelegte Dissertation von Jae-young Park geboren am 22. März 1967 in Seoul/Südkorea Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Hans Henning Hahn Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Matthias Weber Datum der Disputation: 8.7.2005 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Einleitung..........................................................................................1 1.1 Auswahl des Untersuchungsthemas..................................................1 1.2 Wissenschaftliche Fragestellung.......................................................3 1.3 Untersuchungsmethode ....................................................................4 1.4 Auswahl der Literatur.......................................................................6 1.5 Ziel der Untersuchung......................................................................9 2. Historischer Überblick nationaler Teilung.................................11 2.1 Entstehung der Blockbildung......................................................11 2.2 Bedeutung des Kalten Krieges.....................................................13 2.3 Korea und Deutschland als geteilte Nationen............................20 2.3.1 Korea(Südkorea und Nordkorea).................................................21 2.3.2 Deutschland( -

Asia's Exotic Futures in the Far Beyond the Present

ARTICLE .1 Asia’s Exotic Futures in the Far beyond the Present Vahid V. Motlagh Independent Futurist Iran Abstract This paper attempts to deconstruct and challenge the dominant discourses with regard to the longer term futures of Asia. First the mentality of reviving the shining past as well as paying attention to the GDP growth rate in the race of the East to take over the position of leaders from the West is reviewed. An associa- tion is made between a memorable metaphor and the scenario of reviving the shining past. Then some guide- lines are introduced and applied to the far ahead futures of Asia including a) violating old implicit assump- tions by applying what if mechanism, b) identifying and articulating distinct value systems, and c) detecting weak signals that may hint to the next mainstream. Four scenarios are built within the rationale of transforma- tion scenario. The aim is to do exotic futures studies and to create alternative images. Such images not only may help shift the identity of future Asians but also influence today decisions and actions of both Asians and non Asians. Keywords: Asia, East, West, value systems, transformation scenarios, space technology, life technology Introduction In the wake of a new kind of globalization in the modern era sometimes it may appear rather silly to ask a total stranger a very typical question: "Where are you from?" The point is that some people are "placeless" in a sense that they do not belong to a specific country, culture, language, and etc. Placelessness and not having clear and vivid roots may result in potential gains and pains in the life of an individual to the extent that, a related postmodern notion has become fashionable nowa- days: to have "multiple identities" (Giridharadas, 2010). -

Dem Lernen Widmet Sich Der Edle Mensch

Eberhard Schoenfeldt Dem Lernen widmet sich der edle Mensch Bildung und Ausbildung in Korea (Republik) Studien zu einem konfuzianisch geprägten Land Kassel 2000 Das diesser Veröffentlichung zugrundeliegende Vorhaben im Rahmen des Be rufsbildungswissenschaftleraustausches (BBWA) von der Carl Duisberg Ge sellschaft e. V. mit Mitteln des Bundesministeriums für Bildung und Forschung gefördert. (Förderungszeichen: G 9013.008) Das Werk ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Sofern eine elektronische Version dieses Werkes auf einem Server bereitgestellt wird, sind Vervielfältigungen nur zum persönlichen Gebrauch gestattet. Dem Lernen widmet sich der edle Mensch Bildung und Ausbildung in Korea (Republik) Studien zu einem konfuzianisch geprägten Land Eberhard Schoenfeldt Universität Gesamthochschule Kassel • Institut für Berufsbildung Berufs- und Wirtschaftspädagogik Band 30 Kassel: Universitätsbibliothek, 2000 ISBN: 3-89792-024-7 Bezugsbedingungen: Preis: 20,-- DM zuzüglich Porto- und Versandkosten Bestellungen an: Institut für Berufsbildung der Universität Gesamthochschule Kassel Fachbereich 10, Heinrich-Plett-Str. 40 34109 Kassel, Dr. Raimund Dröge Prof. Jae-Won Lee dem grand old man der technischen Bildung in Korea (Republik) in Verbundenheit zugeeignet Vorwort Seit der Veröffentlichung meines Buches "Der Edle ist kein Instrument - Bildung und Ausbildung in Korea (Republik)" sind einige Jahre vergangen. Mehrere weitere Forschungsaufenthalte in Südkorea und weiteres Literaturstudium brach ten verbesserte Kenntnisse und neue Einsichten. Eigene Studien und Auftrags forschung für den DAAD ließen Arbeiten entstehen, die teilweise öffentlich nicht zugängig sind. So kam es zur Überlegung, ein weiteres Buch zur Bildung und Ausbildung in Korea vorzulegen. Ganz zufrieden bin ich mit dem Ergebnis nicht. Es ist schwierig, aus verschiede nen Texten ein in sich stimmiges Buch zur erarbeiten. Überschneidungen und Wiederholungen sind so gut es ging vermieden worden. -

Soh-Joseon-Kingdom.Pdf

Asia-Pacific Economic and Business History Conference, Berkeley, 2011 (Feb. 18-20): Preliminary Draft Institutional Differences and the Great Divergence:* Comparison of Joseon Kingdom with the Great Britain Soh, ByungHee Professor of Economics Kookmin University, Seoul, Korea e-mail: [email protected] Abstract If modern Koreans in the 20th century could achieve a remarkable economic growth through industrialization, why couldn’t their ancestors in Joseon Kingdom in early modern period achieve an industrial revolution at that time? This is the fundamental question of this paper. There existed several social and institutional constraints in Joseon Kingdom (1392-1897 A.D.) in the 17th through 19th centuries that made her industrial development impossible. The strictly defined social classes and the ideology of the ruling class deprived Joseon Kingdom of the entrepreneurial spirit and the incentives to invent new technology necessary for industrial development. Markets and foreign trades were limited and money was not used in transaction until late 17th century. Technicians and engineers were held in low social esteem and there was no patent to protect an inventor’s right. The education of Confucian ethical codes was intended to inculcate loyalty to the ruling class Yangban and the King. The only way to get out of the hard commoner’s life was to pass the national civil service examination to become a scholar-bureaucrat. Joseon Kingdom was a tributary country to Qing Dynasty and as such it had to be careful about technological and industrial development not to arouse suspicion from Qing. Joseon was not an incentivized society while the Great Britain was an incentivized society that was conducive to Industrial Revolution. -

Country Coding Units

INSTITUTE Country Coding Units v11.1 - March 2021 Copyright © University of Gothenburg, V-Dem Institute All rights reserved Suggested citation: Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, and Lisa Gastaldi. 2021. ”V-Dem Country Coding Units v11.1” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. Funders: We are very grateful for our funders’ support over the years, which has made this ven- ture possible. To learn more about our funders, please visit: https://www.v-dem.net/en/about/ funders/ For questions: [email protected] 1 Contents Suggested citation: . .1 1 Notes 7 1.1 ”Country” . .7 2 Africa 9 2.1 Central Africa . .9 2.1.1 Cameroon (108) . .9 2.1.2 Central African Republic (71) . .9 2.1.3 Chad (109) . .9 2.1.4 Democratic Republic of the Congo (111) . .9 2.1.5 Equatorial Guinea (160) . .9 2.1.6 Gabon (116) . .9 2.1.7 Republic of the Congo (112) . 10 2.1.8 Sao Tome and Principe (196) . 10 2.2 East/Horn of Africa . 10 2.2.1 Burundi (69) . 10 2.2.2 Comoros (153) . 10 2.2.3 Djibouti (113) . 10 2.2.4 Eritrea (115) . 10 2.2.5 Ethiopia (38) . 10 2.2.6 Kenya (40) . 11 2.2.7 Malawi (87) . 11 2.2.8 Mauritius (180) . 11 2.2.9 Rwanda (129) . 11 2.2.10 Seychelles (199) . 11 2.2.11 Somalia (130) . 11 2.2.12 Somaliland (139) . 11 2.2.13 South Sudan (32) . 11 2.2.14 Sudan (33) . -

Languages of New York State Is Designed As a Resource for All Education Professionals, but with Particular Consideration to Those Who Work with Bilingual1 Students

TTHE LLANGUAGES OF NNEW YYORK SSTATE:: A CUNY-NYSIEB GUIDE FOR EDUCATORS LUISANGELYN MOLINA, GRADE 9 ALEXANDER FFUNK This guide was developed by CUNY-NYSIEB, a collaborative project of the Research Institute for the Study of Language in Urban Society (RISLUS) and the Ph.D. Program in Urban Education at the Graduate Center, The City University of New York, and funded by the New York State Education Department. The guide was written under the direction of CUNY-NYSIEB's Project Director, Nelson Flores, and the Principal Investigators of the project: Ricardo Otheguy, Ofelia García and Kate Menken. For more information about CUNY-NYSIEB, visit www.cuny-nysieb.org. Published in 2012 by CUNY-NYSIEB, The Graduate Center, The City University of New York, 365 Fifth Avenue, NY, NY 10016. [email protected]. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Alexander Funk has a Bachelor of Arts in music and English from Yale University, and is a doctoral student in linguistics at the CUNY Graduate Center, where his theoretical research focuses on the semantics and syntax of a phenomenon known as ‘non-intersective modification.’ He has taught for several years in the Department of English at Hunter College and the Department of Linguistics and Communications Disorders at Queens College, and has served on the research staff for the Long-Term English Language Learner Project headed by Kate Menken, as well as on the development team for CUNY’s nascent Institute for Language Education in Transcultural Context. Prior to his graduate studies, Mr. Funk worked for nearly a decade in education: as an ESL instructor and teacher trainer in New York City, and as a gym, math and English teacher in Barcelona. -

The Syrian Civil War: a Proxy War in the 21St Century a Senior Research Thesis California State University Maritime Academy Felipe I

1 The Syrian Civil War: A Proxy War in the 21st Century A Senior Research Thesis California State University Maritime Academy Felipe I. Rosales The Syrian Civil War: A Proxy War in the 21st Century 2 Abstract The Syrian Civil War is one of the most devastating conflicts of the 21st century and the cause of the worst humanitarian crisis in recent history. It stems between the ruling Al-Assad Regime and a series of opposition rebel groups. The Assad Regime has had the backing of this historical ally, the Russian Federation. Rebel forces have had the continued backing from a collation between western nations, led by the United States. The purpose of this thesis is to determine if the Syrian Civil War was a proxy war between the United States and Russia, and to determine what it means for the future of US-Russia relations. SInce the end of the Second World War and the rise of the nuclear deterrent, war by proxy has become a common strategy used by larger powers. If the Syrian Civil War is truly a proxy war between the United States and Russia, it brings to question the validity of the end of the Cold War. By comparing it to previous Cold War-era proxy wars, we can derive the features that make up a proxy war and apply them to the Syrian Civil War. This thesis uses several precious proxy wars as case studies. These include the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and the Afghan-Soviet War. While each of these was a very different war, they each share a handful of similarities that make them Proxy Wars. -

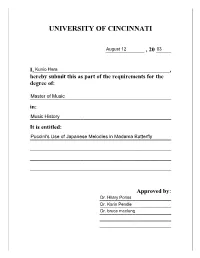

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI _____________ , 20 _____ I,______________________________________________, hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: ________________________________________________ in: ________________________________________________ It is entitled: ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ Approved by: ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ PUCCINI’S USE OF JAPANESE MELODIES IN MADAMA BUTTERFLY A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC in the Division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music 2003 by Kunio Hara B.M., University of Cincinnati, 2000 Committee Chair: Dr. Hilary Poriss ABSTRACT One of the more striking aspects of exoticism in Puccini’s Madama Butterfly is the extent to which the composer incorporated Japanese musical material in his score. From the earliest discussion of the work, musicologists have identified many Japanese melodies and musical characteristics that Puccini used in this work. Some have argued that this approach indicates Puccini’s preoccupation with creating an authentic Japanese setting within his opera; others have maintained that Puccini wanted to produce an exotic atmosphere -

Kultur Korea 한국문화 Ausgabe 4/2010 EDITORIAL

Kultur Korea 한국문화 Ausgabe 4/2010 EDITORIAL Liebe Leserinnen, liebe Leser, derzeit leben 6,7 Millionen Menschen mit ausländischem Pass in Deutschland. 23.550 oder 0,5 Prozent davon sind Südkoreaner, 1.268 Nordkoreaner. Die südkoreanischen Staatsbürger teilen sich in 13.625 Titelbild: Hyun Myung Jang Frauen und 9.925 Männer auf. Im letzten Jahr wurden 146 Personen Der koreanische Tenor Yosep Kang im REDDRESS mit südkoreanischem Pass in Deutschland eingebürgert und zwi- der koreanischen Künstlerin Aamu Song. schen 2002 und 2009 insgesamt 1.601 Personen, so die Zahlen des Die Aufnahme entstand im Mai 2008 bei einem Konzert im Rahmen des DMY International Statistischen Bundesamtes vom 31.12.2009. In diesen Statistiken sind Design Festival Berlin 2008 in der St. Elisabeth- die deutschen Staatsbürger mit koreanischen Wurzeln und deren Kirche. Nachkommen nicht enthalten. Obwohl die Zahl der in Deutschland lebenden Koreaner oder Menschen koreanischer Herkunft relativ gering ist, wird Korea aufgrund seiner zunehmenden politischen und wirtschaftlichen Bedeutung allmählich stärker in der deutschen Öffentlichkeit wahrgenommen. Die Zahl der Deutschen steigt, die beruflich oder im Rahmen ihres Studiums mit Korea zu tun haben. Natürlich ist das Wis- sen über Korea im Gegensatz zu dem über China oder Japan immer noch begrenzt. Dies zu ändern, ist unsere Aufgabe - und Kultur Korea ein kleiner Beitrag, diesem Anspruch gerecht zu werden. Wie ist es, als Koreaner in Deutschland zu leben, und wo kann man hier koreanische Atmosphäre und koreanische Kultur erleben? Die Oktober-Ausgabe unseres Magazins befasst sich mit dem Thema „Koreanisches Leben in Deutschland“ und geht diesen und anderen Fragen nach. Wie immer wünschen wir Ihnen viel Freude beim Lesen! Die Mitarbeiter des Koreanischen Kulturzentrums 2 3 INHALT Spezial: Koreanisches Leben in Deutschland 41 Gedanken zur Zusammenarbeit von Deutschen und MENSCHEN Koreanern in einer sich globalisierenden Welt im Bundesland Thüringen von Dr. -

Acceptance of Western Piano Music in Japan and the Career of Takahiro Sonoda

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE THE ACCEPTANCE OF WESTERN PIANO MUSIC IN JAPAN AND THE CAREER OF TAKAHIRO SONODA A DOCUMENT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS By MARI IIDA Norman, Oklahoma 2009 © Copyright by MARI IIDA 2009 All Rights Reserved. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My document has benefitted considerably from the expertise and assistance of many individuals in Japan. I am grateful for this opportunity to thank Mrs. Haruko Sonoda for requesting that I write on Takahiro Sonoda and for generously providing me with historical and invaluable information on Sonoda from the time of the document’s inception. I must acknowledge my gratitude to following musicians and professors, who willingly told of their memories of Mr. Takahiro Sonoda, including pianists Atsuko Jinzai, Ikuko Endo, Yukiko Higami, Rika Miyatani, Y ōsuke Niin ō, Violinist Teiko Maehashi, Conductor Heiichiro Ōyama, Professors Jun Ozawa (Bunkyo Gakuin University), Sh ūji Tanaka (Kobe Women’s College). I would like to express my gratitude to Teruhisa Murakami (Chief Concert Engineer of Yamaha), Takashi Sakurai (Recording Engineer, Tone Meister), Fumiko Kond ō (Editor, Shunju-sha) and Atsushi Ōnuki (Kajimoto Music Management), who offered their expertise to facilitate my understanding of the world of piano concerts, recordings, and publications. Thanks are also due to Mineko Ejiri, Masako Ōhashi for supplying precious details on Sonoda’s teaching. A special debt of gratitude is owed to Naoko Kato in Tokyo for her friendship, encouragement, and constant aid from the beginning of my student life in Oklahoma. I must express my deepest thanks to Dr.