Fragmenting History: Prostitutes, Hostesses, and Actresses at The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

America's Withdrawal from Siberia and Japan-US Relations

The Japanese Journal of American Studies, No. 24 (2013) America’s Withdrawal from Siberia and Japan-US Relations Shusuke TAKAHARA* INTRODUCTION Japan-US relations after the Russo-Japanese War (1904–5) were gradually strained over the Open Door in Manchuria, the naval arms race in the Pacific, and Japanese immigration into the United States. After the Russo-Japanese War, Japan emerged as a regional power and proceeded to expand its interests in East Asia and the Pacific. The United States also emerged as an East Asian power in the late nineteenth century and turned its interest to having an Open Door in China and defending the Western Pacific. During World War I the relationship of the two countries deteriorated due to Japanese expansion into mainland China (Japan’s Twenty-One Demands on China in 1915). As the Lansing-Ishii agreement (1917) indicated, their joint war effort against Germany did little to diminish friction between Japan and the United States. After World War I, however, the Wilson administration began to shift its policy toward Copyright © 2013 Shusuke Takahara. All rights reserved. This work may be used, with this notice included, for noncommercial purposes. No copies of this work may be distributed, electronically or otherwise, in whole or in part, without permission from the author. *Associate Professor, Kyoto Sangyo University 87 88 SHUSUKE TAKAHARA Japan from maintaining the status-quo to warning against Japanese acts. Wilson hoped to curb Japanese expansion in East Asia and the Pacific without isolating it by cooperating in the establishment of a new Chinese consortium and a joint expedition to Siberia, as well as in founding the League of Nations. -

Fanning the Flames: Fandoms and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan

FANNING THE FLAMES Fans and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan Edited by William W. Kelly Fanning the Flames SUNY series in Japan in Transition Jerry Eades and Takeo Funabiki, editors Fanning the Flames Fans and Consumer Culture in Contemporary Japan EDITED BY WILLIAM W. K ELLY STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK PRESS Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 2004 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. For information, address State University of New York Press, 90 State Street, Suite 700, Albany, NY 12207 Production by Kelli Williams Marketing by Michael Campochiaro Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Fanning the f lames : fans and consumer culture in contemporary Japan / edited by William W. Kelly. p. cm. — (SUNY series in Japan in transition) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-7914-6031-2 (alk. paper) — ISBN 0-7914-6032-0 (pbk. : alk.paper) 1. Popular culture—Japan—History—20th century. I. Kelly, William W. II. Series. DS822.5b. F36 2004 306'.0952'09049—dc22 2004041740 10987654321 Contents List of Illustrations vii Acknowledgments ix Introduction: Locating the Fans 1 William W. Kelly 1 B-Boys and B-Girls: Rap Fandom and Consumer Culture in Japan 17 Ian Condry 2 Letters from the Heart: Negotiating Fan–Star Relationships in Japanese Popular Music 41 Christine R. -

Visit to the Philippines

Volume 14 | Issue 5 | Number 3 | Article ID 4864 | Mar 01, 2016 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Political Agenda Behind the Japanese Emperor and Empress’ “Irei” Visit to the Philippines Kihara Satoru, Satoko Oka Norimatsu Emperor Akihito and empress Michiko of Japan dead as gods," cannot be easily translated into visited the Philippines from January 26 to 30, Anglophone culture. The word "irei" has a 2016. It was the first visit to the country by a connotation beyond "comforting the spirit" of Japanese emperor since the end of the Asia- the dead, which embeds in the word the Pacific War. The pair's first visit was in 1962 possibility of the "comforted spirit being when they were crown prince and princess. elevated to a higher spirituality" to the level of "deities/gods," which can even become "objects The primary purpose of the visit was to "mark of spiritual worship."3 the 60th anniversary of the normalization of bilateral diplomatic relations" in light of the Shintani's argument immediately suggests that "friendship and goodwill between the two we consider its Shintoist, particularly Imperial nations."1 With Akihito and Michiko's "strong Japan's state-sanctioned Shintoist significance wishes," at least as it was reported so widely in when the word "irei" is used to describe the the Japanese media,2 two days out of the five- Japanese emperor and empress' trips to day itinerary were dedicated to "irei 慰霊," that remember the war dead. This is particularly the is, to mourn those who perished under Imperial case given the ongoing international Japan's occupation of the country fromcontroversy over Yasukuni Shrine, which December 1941 to August 1945. -

RACIAL EQUALITY BILL: JAPANESE PROPOSAL at PARIS PEACE CONFERENCE: DIPLOMATIC MANOEUVRES; and REASONS for REJECTION by Shizuka

RACIAL EQUALITY BILL: JAPANESE PROPOSAL AT PARIS PEACE CONFERENCE: DIPLOMATIC MANOEUVRES; AND REASONS FOR REJECTION By Shizuka Imamoto B.A. (Hiroshima Jogakuin University, Japan), Graduate Diploma in Language Teaching (University of Technology Sydney, Australia) A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts (Honours) at Macquarie University. Japanese Studies, Department of Asian Languages, Division of Humanities, College of Humanities and Social Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney Australia. 2006 DECLARATION I declare that the present research work embodied in the thesis entitled, Racial Equality Bill: Japanese Proposal At Paris Peace Conference: Diplomatic Manoeuvres; And Reasons For Rejection was carried out by the author at Macquarie Japanese Studies Centre of Macquarie University of Sydney, Australia during the period February 2003 to February 2006. This work has not been submitted for a higher degree to any other university or institution. Any published and unpublished materials of other writers and researchers have been given full acknowledgement in the text. Shizuka Imamoto ii TABLE OF CONTENTS DECLARATION ii TABLE OF CONTENTS iii SUMMARY ix DEDICATION x ACKNOWLEDGEMENT xi INTRODUCTION 1 1. Area Of Study 1 2. Theme, Principal Question, And Objective Of Research 5 3. Methodology For Research 5 4. Preview Of The Results Presented In The Thesis 6 End Notes 9 CHAPTER ONE ANGLO-JAPANESE RELATIONS AND WORLD WAR ONE 11 Section One: Anglo-Japanese Alliance 12 1. Role Of Favourable Public Opinion In Britain And Japan 13 2. Background Of Anglo-Japanese Alliance 15 3. Negotiations And Signing Of Anglo-Japanese Alliance 16 4. Second Anglo-Japanese Alliance 17 5. Third Anglo-Japanese Alliance 18 Section Two: Japan’s Involvement In World War One 19 1. -

Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei

Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei By ©2016 Alison Miller Submitted to the graduate degree program in the History of Art and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Maki Kaneko ________________________________ Dr. Sherry Fowler ________________________________ Dr. David Cateforis ________________________________ Dr. John Pultz ________________________________ Dr. Akiko Takeyama Date Defended: April 15, 2016 The Dissertation Committee for Alison Miller certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Mother of the Nation: Femininity, Modernity, and Class in the Image of Empress Teimei ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Maki Kaneko Date approved: April 15, 2016 ii Abstract This dissertation examines the political significance of the image of the Japanese Empress Teimei (1884-1951) with a focus on issues of gender and class. During the first three decades of the twentieth century, Japanese society underwent significant changes in a short amount of time. After the intense modernizations of the late nineteenth century, the start of the twentieth century witnessed an increase in overseas militarism, turbulent domestic politics, an evolving middle class, and the expansion of roles for women to play outside the home. As such, the early decades of the twentieth century in Japan were a crucial period for the formation of modern ideas about femininity and womanhood. Before, during, and after the rule of her husband Emperor Taishō (1879-1926; r. 1912-1926), Empress Teimei held a highly public role, and was frequently seen in a variety of visual media. -

Japan's Inland Sea , Setouchi Setouchi, Which Is Celebrated As

Japan's Inland Sea, Setouchi Spectacular Seto Inland Sea A vast, calm sea and islands as far as the eye can see. The Seto Inland Sea, which is celebrated as "The Aegean Sea of the East," is blessed with nature and gentle light. It has a beautiful way of life, and the culture created by locals is still alive. Art, activities, beautiful scenery and the food of this place with a warm climate are all part of the appeal. Each experience you have here is sure to become a special memory. 2 3 Hiroshima Okayama Seto Inland Sea Hiroshima is the central city of Chugoku The Okayama area has flourished region. Hiroshima Prefecture is dotted as an area alive with various culture with Itsukushima Shrine, which has an including swords, Bizen ware and Area Information elegant torii gate standing in the sea; the other handicrafts. Because of its Atomic Bomb Dome that communicates Tottori Prefecture warm climate, fruits such as peaches the importance of peace; and many and muscat grapes are actively other attractions worth a visit. It also grown there. It is also dotted with has world-famous handicrafts such as places where you can see the islands Kumano brushes. of the Seto Inland Sea. Photo taken by Takemi Nishi JAPAN Okayama Hyogo Shimane Prefecture Prefecture Prefecture Fukuoka Sea of Japan Seto Inland Sea Airport Kansai International Airport Setouchi Hiroshima Area Prefecture Seto Inland Sea Hyogo Hyogo Prefecture is roughly in the center of the Japanese archipelago. Hiroshima It has the Port of Kobe, which plays Yamaguchi Port an important role as the gateway of Prefecture Kagawa Prefecture Japan. -

Geography & Climate

Web Japan http://web-japan.org/ GEOGRAPHY AND CLIMATE A country of diverse topography and climate characterized by peninsulas and inlets and Geography offshore islands (like the Goto archipelago and the islands of Tsushima and Iki, which are part of that prefecture). There are also A Pacific Island Country accidented areas of the coast with many Japan is an island country forming an arc in inlets and steep cliffs caused by the the Pacific Ocean to the east of the Asian submersion of part of the former coastline due continent. The land comprises four large to changes in the Earth’s crust. islands named (in decreasing order of size) A warm ocean current known as the Honshu, Hokkaido, Kyushu, and Shikoku, Kuroshio (or Japan Current) flows together with many smaller islands. The northeastward along the southern part of the Pacific Ocean lies to the east while the Sea of Japanese archipelago, and a branch of it, Japan and the East China Sea separate known as the Tsushima Current, flows into Japan from the Asian continent. the Sea of Japan along the west side of the In terms of latitude, Japan coincides country. From the north, a cold current known approximately with the Mediterranean Sea as the Oyashio (or Chishima Current) flows and with the city of Los Angeles in North south along Japan’s east coast, and a branch America. Paris and London have latitudes of it, called the Liman Current, enters the Sea somewhat to the north of the northern tip of of Japan from the north. The mixing of these Hokkaido. -

Notizen 1312.Indd

27 Feature II Franz Eckert und „seine“ Nationalhymnen. Eine Einführung1 von Prof. Dr. Hermann Gottschewski und Prof. Dr. Kyungboon Lee Der preußische Militärmusiker Franz Eckert2, geboren 1852, wurde 1879 als Musiklehrer nach Japan berufen, wo er kurz vor seinem 27. Geburtstag eintraf. Er war dort bis 1899 in ver- schiedenen Positionen tätig, insbesondere als musikalischer Mentor der Marinekapelle. Für mehrere Jahre unterrichtete er auch an der To- yama Armeeschule, außerdem an der Musik- akademie Tokyo und nicht zuletzt an der Musi- kabteilung des Kaiserhofes. In die Zeit seines Wirkens in Japan fällt der Japanisch-Chinesi- sche Krieg, in dem die Militärmusik einen sehr großen Einfluss auf den öffentlichen Musikge- schmack gewann. Von der musikhistorischen Forschung wird dieser Einfluss als einer der wesentlichen Faktoren für die Durchsetzung der westlichen Musik in der modernen japani- schen Musikkultur gesehen. Abb. 1: Aus dem Nachruf Eckert von 1926, in: Mitteilungen der Deutschen Gesellschaft 1899 kehrte Eckert zunächst nach Deutschland für Natur- und Völkerkunde Ostasiens, zurück, aber nach einer kurzen Interimszeit in Band XXI. Dieser Nachruf fehlt in dem Berlin erhielt er einen Ruf an den koreanischen Nachdruck der Mitteilungen von 1965. 1 Dieses Feature geht auf 2 Vorträge zurück, die von den Autoren am 18.9.2013 in der OAG gehalten wurden. 2 Die bisher eingehendste Forschung zu Eckerts Biographie ist von Nakamura Rihei: Yōgaku Dōnyūsha no Kiseki ‒ Nihon Kindai Yōgaku-shi Josetsu (Die Spuren der Einführer westlicher Musik ‒ Eine Einführung in die Geschichte westlicher Musik in der japanischen Moderne), Tōsui Shobō 1993, S. 235- 363. Die grundlegendste Forschung zu Eckerts koreanischen Jahren ist von Namgung Yoyŏl: Gaehwagi ŭi Hanguk-ŭmak ‒ Franz Eckert rŭl jungsim-ŭro (Die koreanische Musik der Aufklärungszeit, insbesondere über Franz Eckert), Seoul: Segwang Ŭmak Chulpanja, 1987. -

I TEAM JAPAN: THEMES of 'JAPANESENESS' in MASS MEDIA

i TEAM JAPAN: THEMES OF ‘JAPANESENESS’ IN MASS MEDIA SPORTS NARRATIVES A Dissertation submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Michael Plugh July 2015 Examining Committee Members: Fabienne Darling-Wolf, Advisory Chair, Media and Communication Doctoral Program Nancy Morris, Media and Communication Doctoral Program John Campbell, Media and Communication Doctoral Program Lance Strate, External Member, Fordham University ii © Copyright 2015 by MichaelPlugh All Rights Reserved iii Abstract This dissertation concerns the reproduction and negotiation of Japanese national identity at the intersection between sports, media, and globalization. The research includes the analysis of newspaper coverage of the most significant sporting events in recent Japanese history, including the 2014 Koshien National High School Baseball Championships, the awarding of the People’s Honor Award, the 2011 FIFA Women’s World Cup, wrestler Hakuho’s record breaking victories in the sumo ring, and the bidding process for the 2020 Olympic Games. 2054 Japanese language articles were examined by thematic analysis in order to identify the extent to which established themes of “Japaneseness” were reproduced or renegotiated in the coverage. The research contributes to a broader understanding of national identity negotiation by illustrating the manner in which established symbolic boundaries are reproduced in service of the nation, particularly via mass media. Furthermore, the manner in which change is negotiated through processes of assimilation and rejection was considered through the lens of hybridity theory. iv To my wife, Ari, and my children, Hiroto and Mia. Your love sustained me throughout this process. -

The Lesson of the Japanese House

Structural Studies, Repairs and Maintenance of Heritage Architecture XV 275 LEARNING FROM THE PAST: THE LESSON OF THE JAPANESE HOUSE EMILIA GARDA, MARIKA MANGOSIO & LUIGI PASTORE Politecnico di Torino, Italy ABSTRACT Thanks to the great spiritual value linked to it, the Japanese house is one of the oldest and most fascinating architectural constructs of the eastern world. The religion and the environment of this region have had a central role in the evolution of the domestic spaces and in the choice of materials used. The eastern architects have kept some canons of construction that modern designers still use. These models have been source of inspiration of the greatest minds of the architectural landscape of the 20th century. The following analysis tries to understand how such cultural bases have defined construction choices, carefully describing all the spaces that characterize the domestic environment. The Japanese culture concerning daily life at home is very different from ours in the west; there is a different collocation of the spiritual value assigned to some rooms in the hierarchy of project prioritization: within the eastern mindset one should guarantee the harmony of spaces that are able to satisfy the spiritual needs of everyone that lives in that house. The Japanese house is a new world: every space is evolving thanks to its versatility. Lights and shadows coexist as they mingle with nature, another factor in understanding the ideology of Japanese architects. In the following research, besides a detailed description of the central elements, incorporates where necessary a comparison with the western world of thought. All the influences will be analysed, with a particular view to the architectural features that have influenced the Modern Movement. -

A Brief Summary of Japanese-Ainu Relations and the Depiction of The

The road from Ainu barbarian to Japanese primitive: A brief summary of Japanese-ainu relations in a historical perspective Noémi GODEFROY Centre d’Etudes Japonaises (CEJ) “Populations Japonaises” Research Group Proceedings from the 3rd Consortium for Asian and African Studies (CAAS) “Making a difference: representing/constructing the other in Asian/African Media, Cinema and languages”, 16-18 February 2012, published by OFIAS at the Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, p.201-212 Edward Saïd, in his ground-breaking work Orientalism, underlines that to represent the “Other” is to manipulate him. This has been an instrument of submission towards Asia during the age of European expansion, but the use of such a process is not confined to European domination. For centuries, the relationship between Japan and its northern neighbors, the Ainu, is based on economical domination and dependency. In this regard, the Ainu’s foreignness, impurity and “barbaric appearance” - their qualities as inferior “Others” - are emphasized in descriptive texts or by the regular staging of such diplomatic practices as “barbarian audiences”, thus highlighting the Japanese cultural and territorial superiority. But from 1868, the construction of the Meiji nation-state requires the assimilation and acculturation of the Ainu people. As Japan undergoes what Fukuzawa Yukichi refers to as the “opening to civilization” (文明開化 bunmei kaika) by learning from the West, it also plays the role of the civilizer towards the Ainu. The historical case study of the relationship between Japanese and Ainu from up to Meiji highlights the evolution of Japan’s own self-image and identity, from an emerging state, subduing barbarians, to newly unified state - whose ultramarine relations are inspired by a Chinese-inspired ethnocentrism and rejection of outside influence- during the Edo period, and finally to an aspiring nation-state, seeking to assert itself while avoiding colonization at Meiji. -

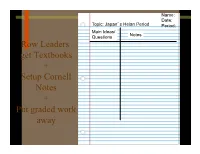

7.5 Heian Notes

Name: Date: Topic: Japan’s Heian Period Period: Main Ideas/ Questions Notes Row Leaders get Textbooks + Setup Cornell Notes + Put graded work away A New Capital • In 794, the Emperor Kammu built a new capital city for Japan, called Heian-Kyo. • Today, it is called Kyoto. • The Heian Period is called Japan’s “Golden Age” Essential Question: What does “Golden Age” mean? Inside the city • Wealthy families lived in mansions surrounded by gardens. A Powerful Family • The Fujiwara family controlled Japan for over 300 years. • They had more power than the emperor and made important decisions for Japan. Beauty and Fashion • Beauty was important in Heian society. • Men and women blackened their teeth. • Women plucked their eyebrows and painted them higher on their foreheads. Beauty and Fashion • Heian women wore as many as 12 silk robes at a time. • Long hair was also considered beautiful. Entertainment • The aristocracy had time for diversions such as go (a board game), kemari (keep the ball in play) and bugaku theater. Art • Yamato-e was a style of Japanese art that reflected nature from the Japanese religion of Shinto. Writing and Literature • The Tale of Genji was written by Murasaki Shikibu, a woman, and is considered the world’s first novel. Japanese Origami Book Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. Blah blah blah blah. .