Just Fashion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018

The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Front Cover Image: Textile Detail of an Evening Dress, circa 1950s, Maker Unknown, Middlesex University Fashion Collection, London, England, F2021AB. The Middlesex University Fashion Collection comprises approximately 450 garments for women and men, textiles, accessories including hats, shoes, gloves, and more, plus hundreds of haberdashery items including buttons and trimmings, from the nineteenth century to the present day. Browse the Middlesex University Fashion Collection at https://tinyurl.com/middlesex-fashion. The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Editor–in–Chief Jennifer Daley Editor Scott Hughes Myerly Proofreader Georgina Chappell Published by The Association of Dress Historians [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org Copyright © 2018 The Association of Dress Historians ISSN 2515–0995 Online Computer Library Centre (OCLC) accession #988749854 The Journal of Dress History is the academic publication of The Association of Dress Historians through which scholars can articulate original research in a constructive, interdisciplinary, and peer reviewed environment. The Association of Dress Historians supports and promotes the advancement of public knowledge and education in the history of dress and textiles. The Association of Dress Historians (ADH) is Registered Charity #1014876 of The Charity Commission for England and Wales. The Journal of Dress History is copyrighted by the publisher, The Association of Dress Historians, while each published author within the journal holds the copyright to their individual article. The Journal of Dress History is circulated solely for educational purposes, completely free of charge, and not for sale or profit. -

Fashion Awards Preview

WWD A SUPPLEMENT TO WOMEN’S WEAR DAILY 2011 CFDA FASHION AWARDS PREVIEW 053111.CFDA.001.Cover.a;4.indd 1 5/23/11 12:47 PM marc jacobs stores worldwide helena bonham carter www.marcjacobs.com photographed by juergen teller marc jacobs stores worldwide helena bonham carter www.marcjacobs.com photographed by juergen teller NEW YORK LOS ANGELES BOSTON LAS VEGAS MIAMI DALLAS SAO PAULO LONDON PARIS SAINT TROPEZ BRUSSELS ANTWERPEN KNOKKE MADRID ATHENS ISTANBUL MOSCOW DUBAI HONG KONG BEIJING SHANGHAI MACAU JAKARTA KUALA LUMPUR SINGAPORE SEOUL TOKYO SYDNEY DVF.COM NEW YORK LOS ANGELES BOSTON LAS VEGAS MIAMI DALLAS SAO PAULO LONDON PARIS SAINT TROPEZ BRUSSELS ANTWERPEN KNOKKE MADRID ATHENS ISTANBUL MOSCOW DUBAI HONG KONG BEIJING SHANGHAI MACAU JAKARTA KUALA LUMPUR SINGAPORE SEOUL TOKYO SYDNEY DVF.COM IN CELEBRATION OF THE 10TH ANNIVERSARY OF SWAROVSKI’S SUPPORT OF THE CFDA FASHION AWARDS AVAILABLE EXCLUSIVELY THROUGH SWAROVSKI BOUTIQUES NEW YORK # LOS ANGELES COSTA MESA # CHICAGO # MIAMI # 1 800 426 3088 # WWW.ATELIERSWAROVSKI.COM BRAIDED BRACELET PHOTOGRAPHED BY MITCHELL FEINBERG IN CELEBRATION OF THE 10TH ANNIVERSARY OF SWAROVSKI’S SUPPORT OF THE CFDA FASHION AWARDS AVAILABLE EXCLUSIVELY THROUGH SWAROVSKI BOUTIQUES NEW YORK # LOS ANGELES COSTA MESA # CHICAGO # MIAMI # 1 800 426 3088 # WWW.ATELIERSWAROVSKI.COM BRAIDED BRACELET PHOTOGRAPHED BY MITCHELL FEINBERG WWD Published by Fairchild Fashion Group, a division of Advance Magazine Publishers Inc., 750 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 EDITOR IN CHIEF ADVERTISING Edward Nardoza ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER, Melissa Mattiace ADVERTISING DIRECTOR, Pamela Firestone EXECUTIVE EDITOR, BEAUTY Pete Born PUBLISHER, BEAUTY INC, Alison Adler Matz EXECUTIVE EDITOR Bridget Foley SALES DEVELOPMENT DIRECTOR, Jennifer Marder EDITOR James Fallon ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER, INNERWEAR/LEGWEAR/TEXTILE, Joel Fertel MANAGING EDITOR Peter Sadera EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, INTERNATIONAL FASHION, Matt Rice MANAGING EDITOR, FASHION/SPECIAL REPORTS Dianne M. -

Revisiting Maternalist Frames Across Cases of Women's Mobilization

WSIF-01856; No of Pages 12 Women's Studies International Forum 51 (2015) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Women's Studies International Forum journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/wsif “Resistance is fertile”1: Revisiting maternalist frames across cases of women’s mobilization Michelle E. Carreon a, Valentine M. Moghadam b a American Studies Program, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN, USA b International Affairs Program and Dept. of Sociology, Northeastern University, Boston, MA, USA article info synopsis Available online xxxx Historically, governments and social movements have evoked images of mothers as nurturing, moral, peaceful, or combative agents. But how is a maternalist frame deployed in different contexts? Who deploys this frame, for what purposes and to what ends? In this article, we present a classification scheme to elucidate the diversity and versatility of maternalist frames through the examination of four distinct categories of cases of women's mobilization from the global South as well as North. Drawing on secondary literature and our own ongoing research, we construct a typology of maternalism-from-above and maternalism-from-below to demon- strate how maternalist frames may serve patriarchal or emancipatory purposes with implications for gender justice and the expansion of citizenship rights. © 2015 Published by Elsevier Ltd. In a 1984 photograph, Orlando Valenzuela depicts a smiling appear, and the diverse ways in which maternal identities are Sandinista woman breastfeeding an infant with an AK-47 invoked in political movements and processes, we revisit the strapped to her back. This image – as with previous ones literature and historical record to offer a classification that depicting Vietnamese militant mothers during the U.S. -

Clothing Upcycling in Otago (Ōtākou) and the Problem of Fast Fashion

Clothing Upcycling in Otago (Ōtākou) and the Problem of Fast Fashion Kirsten Michelle Koch A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a Master of Arts in Sociology at the University of Otago. Abstract Clothing Upcycling in Otago (Ōtākou) This dissertation employs qualitative inductive research methods to address the ‘problem of global fast fashion’. Currently the global production of garments is 62 million tonnes per annum with the majority of production occurring in the world’s poorest countries with limited human rights and labour and environmental protections. From 1994 to 2018 following the easing of trade protections in Developing countries and internationally, there has been a 400% increase in the tonnage of clothing produced internationally. This figure is only escalating. As the level of global clothing waste grows following global clothing consumption rates, the drive to expand the market is fuelling the production of vast amounts of poor-quality textiles and resultant textile waste. In Developed countries 67% of textile waste is commercially on-sold as second-hand clothing to mostly Developing countries. The need for ever cheaper fashion production processes creates ethical concerns for global garment workers and those who sort and dispose of garment waste. Garment workers are 80% women and often women of colour living in Developing countries with few employment options. Meanwhile, textile practitioners and clothing designers in Westernised countries such as New Zealand, are experiencing heightened job precarity and an increasingly diminished space to exercise creativity, sustainable innovation, and social critique. The research interviews local Otago (Ōtākou) textile practitioners who upcycle clothing within their practice assessing how these localised creative actions connect to the larger global ‘slow fashion’ movement, including the ‘clothing upcycling’ movement. -

Council of Fashion Designers of America

Council of Fashion Designers of America ANNUAL REPORT 2017 The mission of the Council of Fashion Designers of America is to strengthen the impact of American fashion in the global economy. B 1 Letter from the Chairwoman, Diane von Furstenberg, and the President and Chief Executive Officer, Steven Kolb In fashion, we respond to the world we live in, a point that was powerfully driven home in 2017. We were excited to see talents with broad cultural backgrounds and political ideas begin to express their experiences and beliefs through their collections. Diversity moved into the spotlight in ways we have never seen before. Designers embraced new approaches to business, from varying show formats to disruptive delivery cycles. It was also the year to make your voices heard, and CFDA listened. We engaged in civic initiatives important to our industry and partnered with Planned Parenthood, the ACLU, and FWD.us. We also relaunched our CFDA Health Initiative with guidelines to help those impacted by sexual assault or other forms of abuse. There’s no going back. In 2018, CFDA is moving ahead at full speed with an increased focus on inclusivity and women in fashion, the latter through an exciting new study with Glamour magazine. We may be a reflection of the world we live in, but we also work hard to make that world a better place. Altruism, after all, never goes out of style. 3 CFDA STRENGTHENED PILLARS WITH MISSION-DRIVEN ACTIONS MEMBERSHIP Fashion Professional Fashion Civic+ Retail Partnership Week + Market Development Supply Chain Philanthropy Opportunities SUSTAINABILITY INDUSTRY ENGAGEMENT SOCIAL AND EDITORIAL MARKETING AND EVENTS KEY UNCHANGED MODIFIED NEW PROVIDED INITIATIVES RELEVANT TO DESIGNERS EMERITUS AT EVERY STAGE OF CAREER DESIGNERS • Board Engagement • Philanthropy and Civic ICONIC Responsibility DESIGNERS • Mentorship • Editorial Visibility • Board Engagement • Fashion Week • Philanthropy and Civic ESTABLISHED Responsibility DESIGNERS • Mentorship • Editorial Visibility • NETWORK. -

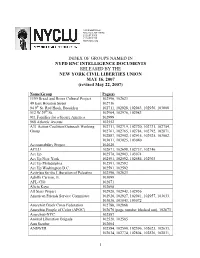

Index of Political Groups Mentioned in the Intelligence Documents

125 Broad Street New York, NY 10004 212.607.3300 212.607.3318 www.nyclu.org INDEX OF GROUPS NAMED IN NYPD RNC INTELLIGENCE DOCUMENTS RELEASED BY THE NEW YORK CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION MAY 16, 2007 (revised May 22, 2007) Name/Group Page(s) 1199 Bread and Roses Cultural Project 102596, 102623 49 East Houston Street 102716 94 9th St. Red Hook, Brooklyn 102711, 102928, 102943, 102956, 103008 512 W 29th St. 102964, 102976, 102983 911 Families for a Secure America 102999 968 Atlantic Avenue 102552 A31 Action Coalition/Outreach Working 102711, 102719, 102720, 102731, 102754, Group 102761, 102765, 102784, 102792, 102871, 102887, 102902, 102915, 102925, 103002, 103011, 103025, 103040 Accountability Project 102620 ACLU 102671, 102698, 102737, 102746 Act Up 102578, 102903, 103074 Act Up New York 102591, 102592, 102684, 102903 Act Up Philadelphia 102591, 102592 Act Up Washington D.C. 102591, 102592 Activists for the Liberation of Palestine 102596, 102623 Adolfo Carrion, Jr. 103099 AFL-CIO 102671 Alicia Keys 102698 All Stars Project 102928, 102943, 102956 American Friends Service Committee 102920, 102927, 102941, 102957, 103033, 103036, 103043, 103072 Anarchist Black Cross Federation 102788, 102868 Anarchist People of Color (APOC) 102670 (page number blacked out), 102673 Anarchist-NYC 102587 Animal Liberation Brigade 102520, 102585 Ann Stauber 102604 ANSWER 102584, 102590, 102596, 102623, 102633, 102634, 102774, 102804, 102826, 102831, 1 102843, 102884, 102900, 102906, 102916, 102919, 102926, 102940, 102952, 102959, 103068, 103076, 103092, 103096 Anthony -

"Understanding Second-Hand Retailing: a Resource Based Perspective of Best Practices Leading to Business Success" (2013)

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2013 Understanding second-hand retailing: A resource based perspective of best practices leading to business success Jinhee Han Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Business Administration, Management, and Operations Commons, and the Sustainability Commons Recommended Citation Han, Jinhee, "Understanding second-hand retailing: A resource based perspective of best practices leading to business success" (2013). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 13636. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/13636 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Understanding second-hand retailing: A resource based perspective of best practices leading to business success by Jinhee Han A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Apparel, Merchandising, and Design Program of Study Committee: Linda S. Niehm, Major Professor Te-Lin Chung Deanne Brocato Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2013 Copyright Jinhee Han, 2013. All right reserved. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES..…………………………………………………….………………... v LIST OF FIGURES……………………………………………………………………… vi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS……………………………………………………………… vii ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………………… viii CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background …………………………………………………….…………… 1 1.2 Significance of Study ……………………………………………………….. 4 1.3 Objective of Study…………………………………………………………… 5 1.4 Definitions of Terms………………………………………………………… 6 CHAPTER TWO: REVIEW OF LITERATURE 2.1 Introduction …………………………………………………….…………… 7 2.2 History of Second-hand Trades …………………………………………….. -

Scale Development of Sustainable Consumption of Clothing Products

sustainability Article Scale Development of Sustainable Consumption of Clothing Products Sunyang Park 1 and Yuri Lee 2,* 1 College of Human Ecology, Seoul National University, Seoul 08826, Korea; [email protected] 2 The Research Institute of Human Ecology, College of Human Ecology, Seoul National University, Seoul 08826, Korea * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-2-880-6843 Abstract: Researchers and companies are paying attention to consumers’ sustainable consumption of clothing products. Clothing industry and fashion consumers have been criticized for a long time due to endless mass production and overconsumption. Despite the efforts of corporations to use sustainability as a marketing tool and an expanding literature exploring consumers’ response to such marketing, the definition of sustainable consumption of clothing products (SCCP) remains unclear. Academic works lack comprehensive discussions regarding SCCP in the perspective of consumers’ awareness and behavior. Furthermore, no widely accepted measurement tool of this concept exists. The validated measurement instrument will eventually help the diagnosing of the mental and behavior status of clothing consumers’ SCCP and further support to establish consumer guidance aimed at resolving sustainability issues related clothing consumption. This study aimed to conceptualize, develop and validate a scale to measure SCCP from the perspective of general clothing consumers. Literature review and interview were used to collect qualitative data for scale item generation. Then, surveys were conducted two times to acquire quantitative data from respondents to purify and validate the scale items. Content analysis, exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis using MPlus were used to explore and predict the data. Based on reliability and validity check, the results are apparent that the scale shows good psychometric properties. -

War of Position on Neoliberal Terrain

Interface: a journal for and about social movements Article Volume 5 (2): 377 - 398 (November 2013) Brissette, War of position on neoliberal terrain Waging a war of position on neoliberal terrain: critical reflections on the counter-recruitment movement Emily Brissette Abstract This paper explores the relationship between neoliberalism and the contemporary movement against military recruitment. It focuses on the way that the counter-recruitment movement is constrained by, reproduces, and in some instances challenges the reigning neoliberal common sense. Engaging with the work of Antonio Gramsci on ideological struggle (what he calls a war of position), the paper critically examines three aspects of counter-recruitment discourse for whether or how well they contribute to a war of position against militarism and neoliberalism. While in many instances counter-recruitment discourse is found to be imbricated with neoliberal assumptions, the paper argues that counter-recruitment work around the poverty draft offers a significant challenge, especially if it can be linked to broader struggles of social transformation. For more than thirty years, a number of peace organizations have waged a (mostly) quiet battle against the presence of military recruiters in American public schools. The war in Iraq brought these efforts to greater public awareness and swelled the ranks of counter-recruitment activists, as many came to see counter-recruitment as a way not only to contest but also to interfere directly with the execution of the war—by disrupting the flow of bodies into the military. While some of this disruption took physical form, as in civil disobedience or guerrilla theater to force the (temporary) closure of recruiting offices, much more of it has been discursive, attempting to counter the narratives the military uses to recruit young people. -

Winter 2020-21 Newsletter

Winter 2020-21, volume XXIV, issue 4 VETERANS FOR PEACE NEWS MINNEAPOLIS/ST. PAUL VETERANS FOR PEACE, CHAPTER 27 Veterans For Peace News is published quar- Save Our VA gets national backing, terly by Mpls./St. Paul Veterans For Peace, continues collaboration with unions Chapter 27. Veterans For Peace works to increase awareness of the costs of war, restrain our government from intervening in the internal affairs of other nations, end the arms race, reduce and even- tually eliminate nuclear weapons, seek justice for veterans and victims of war, and abolish war as an instrument of national policy. We pledge to use democratic and non- violent means to achieve our purpose. To subscribe to this newsletter, Save Our VA and the American Federation of Government Employees rally to stop the please call our office: 612-821-9141 privatization of the VA. Pictured above are VFP members Barry Riesch, Tom Dimond, Mike McDonald, Andy Berman, Dave Logsdon, Tom Bauch, Craig Wood and Jeff Roy Or write: and a number of AFGE union members. Photo from Union Advocate. Veterans For Peace Ch. 27 4200 Cedar Ave, S. #7 Minneapolis, MN 55407 by Arlys Herem and Jeff Roy, expand our efforts. Or e-mail: VFP SOVA Action Committee Minnesota The Campaign’s Outreach Sub- [email protected] Committee contacted over 200 past SOVA he Save Our VA (SOVA) and American activists and is working to build a national net- Our website is: TFederation of Government Employees work of local VFP Action Groups. The www.vfpchapter27.org. rally on October 29th at Hiawatha and Hwy. -

WINTER 2011 Struggles in the Global South Note from the Co-Chair

The PEACECHRONICLE The Newsletter of the Peace and Justice Studies Association Spanning the globe Movements for PEACE emerge everywhere INSIDE THIS ISSUE: News, views, visions, and analyses of cutting-edge movements for peace! AN UPRISING IN EGYPT INTERNATIONAL PEACE TRIBUTE TO GREAT SOULS CHANGES IN GRATITUDE Plus… WINTER 2011 Struggles in the Global South Note from the Co-Chair ................................................ 3 2011 Conference Call .................................................... 4 Facilitating Group Learning The Director’s Cut........................................................ 6 2010 Conference Report-back News and Views ........................................................... 7 New Media Spotlight .................................................. 11 2011 Conference Proposal Call Join or Renew Now! PJSA Membership Form ............ 13 In Memoriam ............................................................. 14 RIP to Three Peacemaking Elders Sources ...................................................................... 18 Archer’s Arrows: Canon Fodder Archer’s Arrows ......................................................... 19 Jobs and Resources ..................................................... 20 Events Calendar ......................................................... 23 Creating a Just and Peaceful World through Research, Action, and Education THE PEACE CHRONICLE WINTER 2011 The Peace and Justice Studies Association Board of Directors Cris Toffolo - Co-Chair Michael Nagler - Co-Chair Matt Meyer - -

Vintage, the First 40 Years: the Emergence and Persistence of Vintage Style in the United States

Vintage, the First 40 Years: The Emergence and Persistence of Vintage Style in the United States By Nancy L. Fischer Abstract This paper historicizes when wearing vintage clothing first became fashionable in the United States. I trace when the trend emerges in the U.S. and explore various ways the press framed secondhand/vintage clothes and anachronistic dressing. I contend that the emergence of vintage occurs as a form of alternative consumption alongside changes that occurred in the U.S. garment industry such as outsourcing and product licensing. These changes led many consumers to seek more authentic consumption experiences. Consumers with cultural capital found in vintage an alternative market for sourcing fashionable street style. Consumers attribute char- acteristics to vintage clothing that are typically part of authenticity discourse such as it being of exceptional quality, original, handcrafted, made from natural fibers, and providing continuity with the past. The authenticity of vintage is symbolically deployed in opposition to contemporary mass-produced clothing and standardized retail shopping experiences. Keywords: Vintage, vintage clothing, retro, secondhand clothing, authenticity, fashion trends, garment industry Fischer, Nancy L.: “Vintage, the first 40 Years” Culture Unbound, Volume 7, 2015: 45-66. Published by Linköping University Electronic Press: http://www.cultureunbound.ep.liu.se I’m gonna take your grandpa style I’m gonna take your grandpa style. No, for real, ask your grandpa, Can I have his hand-me-downs? - Lyrics, “Thrift Shop” by Macklemore and Ryan Lewis, 2013 Introduction In early 2014, rap duo Macklemore and Ryan Lewis won two Grammys for best rap song and best rap performance for “Thrift Shop,” an exuberant celebration of thrift store culture.