"Understanding Second-Hand Retailing: a Resource Based Perspective of Best Practices Leading to Business Success" (2013)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Dakota Town-Country Trade Relations: 1901-1931 P.H

South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange South Dakota State University Agricultural Bulletins Experiment Station 9-1-1932 South Dakota Town-Country Trade Relations: 1901-1931 P.H. Landis Follow this and additional works at: http://openprairie.sdstate.edu/agexperimentsta_bulletins Recommended Citation Landis, P.H., "South Dakota Town-Country Trade Relations: 1901-1931" (1932). Bulletins. Paper 274. http://openprairie.sdstate.edu/agexperimentsta_bulletins/274 This Bulletin is brought to you for free and open access by the South Dakota State University Agricultural Experiment Station at Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bulletins by an authorized administrator of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bulletin 27 4 September, 1932 �� Town-Counlrq Trade Relations 1901-1931 Department of Rural Sociology Agricultural Experiment Station of the South Dakota State College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts Cooperating with the Bureau of Agricultural Economics United States Department of Agriculture Brookings, South Dakota CONTENTS Page 1. Introduction -------------------------------- 3 The Period and its Changes ________________ 3 Plan of Study ---------------------------- 6 Definition of Terms _______________________ 8 II. Factors in the Territorial Distribution of Trade Centers, 1901 to 1931 _____________________ 11 Geographical Factors _____________________ 11 Historical Factors ________________________ 14 III. Changing Life Habits as a Factor in Rural-Urban Trade Relations -------------------------- 15 Changes in Merchandising as Indices of Life IIabits ------------------------------- 15 Per Capita Distribution of Stores __________ 19 Urbanization as a Factor in Change ________ 22 Interdependence of Town and Country ______ 27 IV. -

DG Trip Generation Memorandum.Pdf

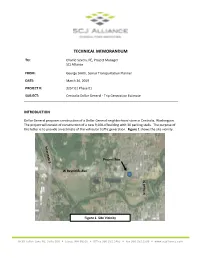

TECHNICAL MEMORANDUM TO: Charlie Severs, PE, Project Manager SCJ Alliance FROM: George Smith, Senior Transportation Planner DATE: March 26, 2019 PROJECT #: 3257.01 Phase 01 SUBJECT: Centralia Dollar General - Trip Generation Estimate INTRODUCTION Dollar General proposes construction of a Dollar General neighborhood store in Centralia, Washington. The project will consist of construction of a new 9,100-sf building with 30 parking stalls. The purpose of this letter is to provide an estimate of the vehicular traffic generation. Figure 1 shows the site vicinity. Project Site W Reynolds Ave N Pearl St N Pearl Figure 1. Site Vicinity 8730 Tallon Lane NE, Suite 200 Lacey, WA 98516 Office 360.352.1465 Fax 360.352.1509 www.scjalliance.com March 26, 2019 Page 2 of 3 PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT Dollar General is proposing construction of a 9,100-sf Dollar General store in Centralia. The development will be located on currently vacant property south of W Reynolds Avenue across the street from Centralia Self Storage. The development will provide one driveway on W Reynolds Avenue. The proposed project will provide 30 parking stalls on-site. The preliminary site plan is attached. SITE-GENERATED TRAFFIC VOLUMES Vehicle trip generation was calculated using the trip generation rates contained in the current edition of the Trip Generation report by the Institute of Transportation Engineers (ITE). The Variety Store category (land-use code #814) was determined to be the most applicable to this project. The following is a quote from the ITE description of the Variety Store Land Use: A variety store is a retail store that sells a broad range of inexpensive items often at a single price. -

Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018

The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Front Cover Image: Textile Detail of an Evening Dress, circa 1950s, Maker Unknown, Middlesex University Fashion Collection, London, England, F2021AB. The Middlesex University Fashion Collection comprises approximately 450 garments for women and men, textiles, accessories including hats, shoes, gloves, and more, plus hundreds of haberdashery items including buttons and trimmings, from the nineteenth century to the present day. Browse the Middlesex University Fashion Collection at https://tinyurl.com/middlesex-fashion. The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Editor–in–Chief Jennifer Daley Editor Scott Hughes Myerly Proofreader Georgina Chappell Published by The Association of Dress Historians [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org Copyright © 2018 The Association of Dress Historians ISSN 2515–0995 Online Computer Library Centre (OCLC) accession #988749854 The Journal of Dress History is the academic publication of The Association of Dress Historians through which scholars can articulate original research in a constructive, interdisciplinary, and peer reviewed environment. The Association of Dress Historians supports and promotes the advancement of public knowledge and education in the history of dress and textiles. The Association of Dress Historians (ADH) is Registered Charity #1014876 of The Charity Commission for England and Wales. The Journal of Dress History is copyrighted by the publisher, The Association of Dress Historians, while each published author within the journal holds the copyright to their individual article. The Journal of Dress History is circulated solely for educational purposes, completely free of charge, and not for sale or profit. -

The Life & Rhymes of Jay-Z, an Historical Biography

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 Omékongo Dibinga, Doctor of Philosophy, 2015 Dissertation directed by: Dr. Barbara Finkelstein, Professor Emerita, University of Maryland College of Education. Department of Teaching and Learning, Policy and Leadership. The purpose of this dissertation is to explore the life and ideas of Jay-Z. It is an effort to illuminate the ways in which he managed the vicissitudes of life as they were inscribed in the political, economic cultural, social contexts and message systems of the worlds which he inhabited: the social ideas of class struggle, the fact of black youth disempowerment, educational disenfranchisement, entrepreneurial possibility, and the struggle of families to buffer their children from the horrors of life on the streets. Jay-Z was born into a society in flux in 1969. By the time Jay-Z reached his 20s, he saw the art form he came to love at the age of 9—hip hop— become a vehicle for upward mobility and the acquisition of great wealth through the sale of multiplatinum albums, massive record deal signings, and the omnipresence of hip-hop culture on radio and television. In short, Jay-Z lived at a time where, if he could survive his turbulent environment, he could take advantage of new terrains of possibility. This dissertation seeks to shed light on the life and development of Jay-Z during a time of great challenge and change in America and beyond. THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 An historical biography: 1969-2004 by Omékongo Dibinga Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2015 Advisory Committee: Professor Barbara Finkelstein, Chair Professor Steve Klees Professor Robert Croninger Professor Derrick Alridge Professor Hoda Mahmoudi © Copyright by Omékongo Dibinga 2015 Acknowledgments I would first like to thank God for making life possible and bringing me to this point in my life. -

Jan Bormeth Vilhelmsen Og Ma

0 ucvbnmqwertyuiopåasdfghjklæøzxcv Executive Summary The master thesis at hand is a study of the Danish retail store chain Tiger and EQT’s decision to acquire a 70% stake in the company. The aim in this thesis is twofold. Firstly, a valuation of Zebra per June 30, 2015, will be conducted. Secondly, an analysis of the value creation during EQT’s ownership period is performed. The main objective in this thesis is to estimate the fair Enterprise Value per June 30, 2015, through a DCF-analysis. Based on Zebra’s strategic position and its historical financial performance, the expected future earnings and cash flow generations were forecasted and resulted in an Enterprise Value of DKK 8,864 million from which the Group accounted for DKK 8,350 million and the Japanese Joint Venture for DKK 515 million. Based on these figures, Zebra’s fair value of equity comprises DKK 7,789 million. Of this figure, EQT’s share of the equity amounts to DKK 5,219 million and DKK 2,874 million when correcting for the 50/50 owned subsidiaries. At EQT’s entry in the beginning of 2013, the purchase price for its stake was DKK 1,600 million, according to different sources, resulting in an IRR for EQT on 26.48% per year. This IRR is satisfying since it is above the expected return for Private Equity investments which historically has a threshold for an IRR on over 20% per year, and in more recent time a threshold between 12-17% per year. The objective in the second part of this thesis is to analyze how EQT has created or destroyed value during its ownership period based on an IRR for Zebra, excluding the Japanese Joint Venture. -

TO: Mayor Craft & Members of the City Council

TO: Mayor Craft & Members of the City Council FROM: Andy Bauer, Director of Planning & Zoning SUBJECT: Dollar General Public Parking Credit Request DATE: November 4, 2013 ISSUE: Jeremy Cobb, representing The Broadway Group, LLC seeks approval from the City Council to purchase 20 parking spaces from the City’s East 1st Street Public Parking Lot in order to meet the minimum parking requirements for the proposed Dollar General at 224 Gulf Shores Parkway. RECOMMENDATION: In accordance with the provisions of Article 14-1 B. 4. Of the Zoning Ordinance Planning Department staff recommends the City Council approve the Dollar General’s request to purchase of 20 public parking spaces within the East 1st Street public parking lot for a fee of $3,000 per space. BACKGROUND: Pursuant to Article 14-1 B. 4. of the Zoning Ordinance, on-street public parking spaces and may be credited towards the required parking when parking credits have been purchased from the City for a fee per parking space as established by the City Council. Dollar General is required 47 parking spaces and the site plan indicates 30 on-site parking spaces. The applicants are requesting to purchase 20 spaces (17 spaces required to meet parking regulations & 3 spaces to account for net parking loss on East 1st Street) from the City’s existing public parking lot on East 1st Street for a total of 47 parking spaces. Planning Commission: At their October 22, 2013 meeting, the Commission voted 6-1 to approve the Dollar General site plan with the following conditions: 1. Pursuant to Article 14-1 B. -

Assessment of Retail and Leisure Planning Policy Kingsway Business Park, Gloucester

Assessment of Retail and Leisure Planning Policy Kingsway Business Park, Gloucester February 2019 Client: Gloucester City Council Report Title: Assessment of Retail and Leisure Planning Policy Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................... 1 2. The Sequential Test ........................................................................................................................................................ 2 3. Impact ........................................................................................................................................................................... 5 4. Summary and Conclusions .......................................................................................................................................... 8 Date: February 2019 Page: 2 Client: Gloucester City Council Report Title: Assessment of Retail and Leisure Planning Policy 1. Introduction 1.1 This advice report has been prepared by Avison Young (‘AY’) in relation to a planning application by Robert Hitchins Limited for the redevelopment of land at Kingsway Business Park for a retail and leisure development. 1.2 This document provides supplementary advice to Gloucester City Council (‘GCC’) on retail, leisure and main town centre use planning policy issues following the completion of our previous advice on this planning application in January 2019. 1.3 This supplementary advice responds -

Carbondale Creative District (PDF)

5TH EDITION Guidebook WIFI LOGIN • Network: Orchard Free Public Wifi • No password WELCOME TO THE SUMMIT A two-day professional development conference for creative entrepreneurs, emerging creatives, municipal and non-profit cultural workers, and creative district leaders. May 5, 2016 Greetings: On behalf of the State of Colorado, it is my distinct pleasure to welcome you to the 5th annual Colorado Creative Industries Summit here in Carbondale. As embodied by this year’s theme, the State of Colorado is embracing a culture of possibility. We are recognized as a leader in building sustainable communities and economies by cultivating creative talent, leveraging local resources, and fostering a sense of place through the arts and innovation. It is our independent spirit at the heart of these movements and what continues to drive us forward, paving the way for others to follow. Colorado’s creative industries have a significant impact on the strength of our economy and continue to play an integral role in our overall vitality. Whether it is a community on the Front Range or in a small rural or mountain town, the creative sector touches all four corners of our state, contributing to the inner workings of what makes us unique. During your time in Carbondale, we hope you will take a moment to celebrate the exceptional variety, skill, and determination inherent within the Colorado creative community. As Coloradans, we all have the good fortune of benefitting from the diverse projects and goods generated by our creative industries. Thank you to everyone who is participating in this year’s summit. -

Clothing Upcycling in Otago (Ōtākou) and the Problem of Fast Fashion

Clothing Upcycling in Otago (Ōtākou) and the Problem of Fast Fashion Kirsten Michelle Koch A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a Master of Arts in Sociology at the University of Otago. Abstract Clothing Upcycling in Otago (Ōtākou) This dissertation employs qualitative inductive research methods to address the ‘problem of global fast fashion’. Currently the global production of garments is 62 million tonnes per annum with the majority of production occurring in the world’s poorest countries with limited human rights and labour and environmental protections. From 1994 to 2018 following the easing of trade protections in Developing countries and internationally, there has been a 400% increase in the tonnage of clothing produced internationally. This figure is only escalating. As the level of global clothing waste grows following global clothing consumption rates, the drive to expand the market is fuelling the production of vast amounts of poor-quality textiles and resultant textile waste. In Developed countries 67% of textile waste is commercially on-sold as second-hand clothing to mostly Developing countries. The need for ever cheaper fashion production processes creates ethical concerns for global garment workers and those who sort and dispose of garment waste. Garment workers are 80% women and often women of colour living in Developing countries with few employment options. Meanwhile, textile practitioners and clothing designers in Westernised countries such as New Zealand, are experiencing heightened job precarity and an increasingly diminished space to exercise creativity, sustainable innovation, and social critique. The research interviews local Otago (Ōtākou) textile practitioners who upcycle clothing within their practice assessing how these localised creative actions connect to the larger global ‘slow fashion’ movement, including the ‘clothing upcycling’ movement. -

Download Ordinance

CITY COMCIL ATLANTA, GEORGIA ORDINANCE BY 19-0-1504 4-' 114 COUNCILMEMBER MARCI COLLIER OVERSTREET AS AMENDED BY ZONING COMMITTEE Z-19-96 AN ORDINANCE TO AMEND THE 1982 ATLANTA ZONING ORDINANCE, AS AMENDED, TO ADD SECTION 16-29.001(87) TO ADD THE DEFINITION OF SMALL DISCOUNT VARIETY STORE; TO AMEND THE C-1 (COMMUNITY BUSINESS), C-2 (COMMERCIAL SERVICE), C-3 (COMMERCIAL RESIDENTIAL), C-4 (CENTRAL AREA COMMERCIAL RESIDENTIAL), C-5 (CENTRAL BUSINESS SUPPORT), I-MIX (INDUSTRIAL MIXED USE DISTRICT), 1-2 (HEAVY INDUSTRIAL DISTRICT), SPI-1 (DOWNTOWN SPECIAL PUBLIC INTEREST DISTRICT), SPI-2 (FORT MCPHERSON SPECIAL PUBLIC INTEREST DISTRICT), SPI-9 (BUCKHEAD VILLAGE DISTRICT), SPI-12 (BUCKHEAD/LENOX STATIONS SPECIAL PUBLIC INTEREST DISTRICT), SPI-15 (LINDBERGH TRANSIT STATION SPECIAL PUBLIC INTEREST DISTRICT), SPI-16 (MIDTOWN SPECIAL PUBLIC INTEREST DISTRICT), SPI-17 (PIEDMONT AVENUE SPECIAL PUBLIC INTEREST DISTRICT), SPI-18 (MECHANICSVILLE NEIGHBORHOOD SPECIAL PUBLIC INTEREST DISTRICT), SPI-20 (GREENBRIAR SPECIAL PUBLIC INTEREST DISTRICT), SPI-21 (HISTORIC WEST END/ADAIR PARK SPECIAL PUBLIC INTEREST DISTRICT), SPI-22 (MEMORIAL DRIVE/OAKLAND CEMETERY SPECIAL PUBLIC INTEREST DISTRICT), PD-MU (PLANNED DEVELOPMENT - MIXED USE DISTRICT), PD-OC (PLANNED DEVELOPMENT - OFFICE-COMMERCIAL DISTRICT), CABBAGETOWN LANDMARK DISTRICT, MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR. LANDMARK DISTRICT, INMAN PARK HISTORIC DISTRICT, PRATT-PULLMAN LANDMARK DISTRICT, NC (NEIGHBORHOOD COMMERCIAL), LW (LIVE WORK DISTRICT), AND MRC (MIXED RESIDENTIAL COMMERCIAL) ZONING DISTRICTS SO AS TO ALLOW SMALL DISCOUNT VARIETY STORES AS A USE; TO REQUIRE A 5,280 FOOT DISTANCE BETWEEN SMALL DISCOUNT VARIETY STORES AS DEFINED BY THIS ORDINANCE; AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES. WHEREAS, small discount variety store means a retail establishment with a floor area less than 12,000 sq. -

The Recording Academy®

® The Recording Academy 3030 Olympic Blvd. • Santa Monica, CA 90404 www.grammy.com JAY Z LEADS NOMINATIONS WITH NINE; KENDRICK LAMAR, MACKLEMORE & RYAN LEWIS, JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE, AND PHARRELL WILLIAMS EACH EARN SEVEN; DRAKE AND BOB LUDWIG EACH GARNER FIVE SARA BAREILLES, DAFT PUNK, KENDRICK LAMAR, MACKLEMORE & RYAN LEWIS, AND TAYLOR SWIFT VIE FOR ALBUM OF THE YEAR AT THE 56TH ANNUAL GRAMMY AWARDS® JAN. 26, 2014, LIVE ON CBS LOS ANGELES (Dec. 06, 2013) — Nominations for the 56th Annual GRAMMY Awards® were announced tonight by The Recording Academy® and reflected one of the most diverse years with the Album Of The Year category alone representing the rap, pop, country and dance/electronica genres, as determined by the voting members of The Academy. Once again, nominations in select categories for the annual GRAMMY Awards were announced on primetime television as part of "The GRAMMY® Nominations Concert Live!! — Countdown To Music's Biggest Night®," a one-hour CBS entertainment special broadcast live from Nokia Theatre L.A. LIVE. The 56th Annual GRAMMY Awards will be held on "GRAMMY Sunday," Jan. 26, 2014, at STAPLES Center in Los Angeles and once again will be broadcast live in high-definition TV and 5.1 surround sound on CBS from 8 – 11:30 p.m. (ET/PT). For updates and breaking news, please visit The Recording Academy's social networks on Twitter and Facebook. For a complete nominations list, please visit www.grammy.com. Jay Z tops the nominations with nine; Kendrick Lamar, Macklemore & Ryan Lewis, Justin Timberlake, and Pharrell Williams each garner seven nods; Drake and mastering engineer Bob Ludwig are up for five awards. -

Scale Development of Sustainable Consumption of Clothing Products

sustainability Article Scale Development of Sustainable Consumption of Clothing Products Sunyang Park 1 and Yuri Lee 2,* 1 College of Human Ecology, Seoul National University, Seoul 08826, Korea; [email protected] 2 The Research Institute of Human Ecology, College of Human Ecology, Seoul National University, Seoul 08826, Korea * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-2-880-6843 Abstract: Researchers and companies are paying attention to consumers’ sustainable consumption of clothing products. Clothing industry and fashion consumers have been criticized for a long time due to endless mass production and overconsumption. Despite the efforts of corporations to use sustainability as a marketing tool and an expanding literature exploring consumers’ response to such marketing, the definition of sustainable consumption of clothing products (SCCP) remains unclear. Academic works lack comprehensive discussions regarding SCCP in the perspective of consumers’ awareness and behavior. Furthermore, no widely accepted measurement tool of this concept exists. The validated measurement instrument will eventually help the diagnosing of the mental and behavior status of clothing consumers’ SCCP and further support to establish consumer guidance aimed at resolving sustainability issues related clothing consumption. This study aimed to conceptualize, develop and validate a scale to measure SCCP from the perspective of general clothing consumers. Literature review and interview were used to collect qualitative data for scale item generation. Then, surveys were conducted two times to acquire quantitative data from respondents to purify and validate the scale items. Content analysis, exploratory factor analysis and confirmatory factor analysis using MPlus were used to explore and predict the data. Based on reliability and validity check, the results are apparent that the scale shows good psychometric properties.