Proud Place in Anti-Fascist Memory, Considered a Decisive Victory Against the Far Right

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stepney in Peace and War the Paintings of Rose L. Henriques

NEWSLETTER OF TOWER HAMLETS LOCAL HISTORY LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES LH&A NEWS November-December 2013 Stepney in Peace and War The paintings of Rose L. Henriques The Foothills, 'Tilbury', bombed second time. Watercolour on paper, Rose L. Henriques. c1941. Our new exhibition is a rare opportunity to see highlights from our collections of paintings by the Jewish philanthropist Rose L. Henriques (1889-1972) which launches here on Thursday 28 November at 6.30pm. This event is open to the public and is co-hosted with the Jewish East End Celebration Society. With her husband Sir Basil, Lady Rose Henriques founded the St George's Jewish Settlement in Betts St, Stepney in 1919. Here, the Henriques developed social welfare facilities and services for the deprived local community ranging from youth clubs to washrooms and open to Jews and non-Jews alike. The Settlement was able to expand into its own new premises in Berner Street in 1929 thanks to funding from philanthropist Bernhard Baron, after whom the building was renamed. Rose was an avid artist, serving on the board of the Whitechapel Gallery, and the watercolours in our collection are a unique record of Stepney around the time of the Second World War. Focussing on the regular activities and everyday landscapes of the besieged borough, her subjects include the clear-up and triage activities of the Civilian Defence Service, the controversial air raid shelter known as "Tilbury", and scenes of bombed out synagogues and churches. She also painted everyday life at the Settlement building where she and Basil lived. This exhibition has been curated by staff with the expert voluntary help of art researcher Sara Ayad. -

The Local Impact of Falling Agricultural Prices and the Looming Prospect Of

CHAPTER SIX `BARLEY AND PEACE': THE BRITISH UNION OF FASCISTS IN NORFOLK, SUFFOLK AND ESSEX, 1938-1940 1. Introduction The local impact of falling agricultural prices and the looming prospectof war with Germany dominated Blackshirt political activity in Norfolk, Suffolk and Essex from 1938. Growing resentment within the East Anglian farming community at diminishing returns for barley and the government's agricultural policy offered the B. U. F. its most promising opportunity to garner rural support in the eastern counties since the `tithe war' of 1933-1934. Furthermore, deteriorating Anglo-German relations induced the Blackshirt movement to embark on a high-profile `Peace Campaign', initially to avert war, and, then, after 3 September 1939, to negotiate a settlement to end hostilities. As part of the Blackshirts' national peace drive, B. U. F. Districts in the area pursued a range of propaganda activities, which were designed to mobilise local anti-war sentiment. Once again though, the conjunctural occurrence of a range of critical external and internal constraints thwarted B. U. F. efforts to open up political space in the region on a `barley and peace' platform. 2. The B. U. F., the `Barley Crisis' and the Farmers' March, 1938-1939 In the second half of 1938, falling agricultural prices provoked a fresh wave of rural agitation in the eastern counties. Although the Ministry of Agriculture's price index recorded a small overall reduction from 89.0 to 87.5 during 1937-1938, cereals due heavy from 1938 and farm crops were particularly affected to the yields the harvests. ' Compared with 1937 levels, wheat prices (excluding the subsidy) dropped by fourteen 2 Malting barley, by 35 per cent, barley by 23 per cent, and oats per cent. -

The Appeal of Fascism to the British Aristocracy During the Inter-War Years, 1919-1939

THE APPEAL OF FASCISM TO THE BRITISH ARISTOCRACY DURING THE INTER-WAR YEARS, 1919-1939 THESIS PRESENTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OFARTS. By Kenna Toombs NORTHWEST MISSOURI STATE UNIVERSITY MARYVILLE, MISSOURI AUGUST 2013 The Appeal of Fascism 2 Running Head: THE APPEAL OF FASCISM TO THE BRITISH ARISTOCRACY DURING THE INTER-WAR YEARS, 1919-1939 The Appeal of Fascism to the British Aristocracy During the Inter-War Years, 1919-1939 Kenna Toombs Northwest Missouri State University THESIS APPROVED Date Dean of Graduate School Date The Appeal of Fascism 3 Abstract This thesis examines the reasons the British aristocracy became interested in fascism during the years between the First and Second World Wars. As a group the aristocracy faced a set of circumstances unique to their class. These circumstances created the fear of another devastating war, loss of Empire, and the spread of Bolshevism. The conclusion was determined by researching numerous books and articles. When events required sacrifice to save king and country, the aristocracy forfeited privilege and wealth to save England. The Appeal of Fascism 4 Contents Chapter One Background for Inter-War Years 5 Chapter Two The Lost Generation 1919-1932 25 Chapter Three The Promise of Fascism 1932-1936 44 Chapter Four The Decline of Fascism in Great Britain 71 Conclusion Fascism After 1940 83 The Appeal of Fascism 5 Chapter One: Background for Inter-War Years Most discussions of fascism include Italy, which gave rise to the movement; Spain, which adopted its principles; and Germany, which forever condemned it in the eyes of the world; but few include Great Britain. -

Cable Street Particulars

For Sale Residential Development Opportunity On behalf of Transport for London February 2018 Land at Cable Street, Shadwell, E1 0DR Excellent development potential Part of the GLA’s Small Sites Small Builders Programme Vacant site located in Tower Hamlets Site area approximately 0.51 acres (0.20 hectares) Adjacent site of approximately 0.29 acres (0.12 hectares) to be retained by the DLR for operational use Long Leasehold (250 years) for sale via informal tender Subject to planning offers invited for affordable housing Bid deadline 12 noon Friday 23rd March 2018 Indicative Boundary 08449 02 03 04 www.london.gov.uk/smallsites GLA Small Sites Programme Residential properties lie to the south of the site on Cable Street and range between 5 and 9 storeys. TfL is delivering a number of small sites to the market Cable Street is a one-way street that forms part of the as part of a pilot scheme for the GLA’s Small Sites Barking to Tower Gateway Cycle Superhighway route. Programme. The programme is intended to: Retained Land Bring small publicly owned sites forward for residential-led development If required, a licence and associated access rights will be granted over the DLR retained land to enable the Invigorate new and emerging ‘sources of developer to: supply’ including small developers, small housing associations, community-led housing a) Implement a hard landscaping scheme, to groups and self builders. improve the outlook and linkage with the residential development. Any landscaping Location designs will need to be compatible with DLR operational uses and materials will need to be The site is situated on Cable Street in Shadwell and is agreed with DLR. -

Limehouse Trail 2017

Trail The lost east end Discover London’s first port, first Chinatown and notorious docklands Time: 2 hours Distance: 3 ½ miles Landscape: urban The East End starts where the City of London finishes, Location: east of the Tower. A short walk from this tourist hub Shadwell, Wapping and Limehouse, leads to places that are much less visited. London E1W and E14 Some of the names are famous: Cable Street, where Start: locals held back the fascist blackshirts; or Limehouse, Tower Gateway DLR Station or where Britain’s first Chinese population gained mythical Tower Hill Underground Station status. Finish: Some are less known, such as Wellclose Square, a Westferry DLR Station Scandinavian square with an occult reputation, and Ratcliff, where ships set sale to explore the New World. Grid reference: TQ 30147 83158 These parts of London were once notorious, home to Keep an eye out for: sailors from across the globe and reputed to be wild and lawless. Now they hold clues to their past, which can be The Old Rose pub at the top of Chigwell Hill, decoded by retracing their borders beside the Thames. a real slice of the lost East End Directions From Tower Hill - avoid the underpass and turn left outside the station to reach Minories, and cross to Shorter Street. From Tower Gateway - take the escalators to street level, turn left on to Minories then left again along Shorter Street. From Shorter Street - Cross Mansell Street and walk along Royal Mint Street. Continue along the street for a few minutes, passing the Artful Dodger pub, then crossing John Fisher Street and Dock Street. -

Cable Street – Road Safety Improvements

Cycle Superhighway 3 Upgrade Cable Street – Road Safety Improvements Response to Consultation March 2015 Cycle Superhighway 3 Upgrade Cable Street – Road Safety Improvements Response to Consultation Published March 2015 Executive summary Between 30 January and 27 February 2015, Transport for London (TfL) consulted on road safety improvements to Cable Street as part of an upgrade to Cycle Superhighway 3. We received 90 direct responses to the consultation, 76 (or 85%) of which supported or partially supported our proposals. After considering all responses, we have decided to proceed with the scheme incorporating the following additional measures to those originally proposed: Reviewing the signal timings at the junction of Cable Street and Cannon Street to maximise the green time available for cyclists Replacing the speed cushion with a sinusoidal hump at the junction of Cable Street and Hardinge Street Extending double yellow lines around junctions but not across the cycle track Subject to final discussions with the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is the highway authority responsible for Cable Street, we expect work to start in summer 2015. We will write to local residents and affected properties before work starts to provide a summary of this consultation, an overview of the updated proposals and an outline of the construction programme. This document explains the processes, responses and outcomes of the recent consultation, and sets out our response to issues commonly raised. Contents 1 Introduction ...................................................................................................... -

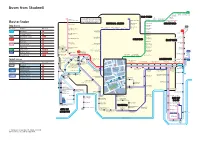

Buses from Shadwell from Buses

Buses from Shadwell 339 Cathall Leytonstone High Road Road Grove Green Road Leytonstone OLD FORD Stratford The yellow tinted area includes every East Village 135 Old Street D3 Hackney Queen Elizabeth Moorfields Eye Hospital bus stop up to about one-and-a-half London Chest Hospital Fish Island Wick Olympic Park Stratford City Bus Station miles from Shadwell. Main stops are for Stratford shown in the white area outside. Route finder Old Ford Road Tredegar Road Old Street BETHNAL GREEN Peel Grove STRATFORD Day buses Roman Road Old Ford Road Ford Road N15 Bethnal Green Road Bethnal Green Road York Hall continues to Bus route Towards Bus stops Great Eastern Street Pollard Row Wilmot Street Bethnal Green Roman Road Romford Ravey Street Grove Road Vallance Road 115 15 Blackwall _ Weavers Fields Grove Road East Ham St Barnabas Church White Horse Great Eastern Street Trafalgar Square ^ Curtain Road Grove Road Arbery Road 100 Elephant & Castle [ c Vallance Road East Ham Fakruddin Street Grove Road Newham Town Hall Shoreditch High Street Lichfield Road 115 Aldgate ^ MILE END EAST HAM East Ham _ Mile End Bishopsgate Upton Park Primrose Street Vallance Road Mile End Road Boleyn 135 Crossharbour _ Old Montague Street Regents Canal Liverpool Street Harford Street Old Street ^ Wormwood Street Liverpool Street Bishopsgate Ernest Street Plaistow Greengate 339 Leytonstone ] ` a Royal London Hospital Harford Street Bishopsgate for Whitechapel Dongola Road N551 Camomile Street 115 Aldgate East Bethnal Green Z [ d Dukes Place continues to D3 Whitechapel Canning -

Copyright Statement This Copy of the Thesis Has Been Supplied On

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk 04 University of Plymouth Research Theses 01 Research Theses Main Collection 2014 Blackshirts and White Wigs: Reflections on Public Order Law and the Political Activism of the British Union of Fascists Channing, Iain Christopher Edward http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/2897 University of Plymouth All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. Copyright Statement This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the author’s prior consent. 1 2 Blackshirts and White Wigs: Reflections on Public Order Law and the Political Activism of the British Union of Fascists by Iain Christopher Edward Channing A thesis submitted to Plymouth University in Partial fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Plymouth Law School March 2013 3 4 Abstract While domestic fascism within the United Kingdom has never critically challenged Parliamentary sovereignty, it has decisively disrupted public order since its roots were established in the inter-war political scene. The violence provoked by Sir Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists (BUF) was one of the stimulating factors behind the enactment of the Public Order Act 1936. -

St George's Estate

St George’s Estate A Neighbourhood Plan St George’s Estate About the Estate The estate comprises properties in: The St George’s Estate was built during Beadnell Court built 1977 the late 1960s and 1970s and is situated in Shadwell, nestled between Betts House built 1937 The Highway and Cable Street en route Betts Street built 2011 to the Tower of London and the City. Brockmer House built 1965 Burlington Court built 2012 Crowder Street built 2011 The estate contains a mix of Hatton House built 1970 maisonettes, bungalows and houses but Noble Court built 1977 is especially notable for the 3 tower blocks that rise up from the middle of Pegswood Court built 1977 the estate, the top floors of which have and 1 9 9 1 Shearsmith House built 1970 Smithfield Court built 1977 and 2 0 1 2 Stockholm House built 1968 Swedenborg Gardens built 1968 and 2 0 1 1 Did You Know? a commanding view over the River The St George’s estate formally Thames and surrounding area. St transferred to EastendHomes in George’s has recently benefitted from January 2006 . regeneration works which has included a number of new flats and maisonettes being built within the estate. St George’s has excellent transport links to the City, Canary Wharf, Bethnal Green and Whitechapel as the Shadwell DLR and Overground stations are nearby as are the D3 and 100 bus routes. As well as being close to the www.eastendhomes.net stalls and shops of Watney Street Market, St George’s is also within walking distance of St Katherine’s Dock with its marina, shops, cafés and restaurants. -

The East End in Colour 1960–1980 the East End in Colour 1960–1980

THE EAST END IN COLOUR 1960–1980 THE EAST END IN COLOUR 1960–1980 The photographs of David Granick from the collections of Tower Hamlets Local History Library & Archives edited by CHRIS DORLEY-BROWN We are an indie publisher making small collectable photobooks out of East London. Our goal is to make books that are both beautiful and accessible. Neither aloof nor plain. We want both collectors and everyday folk to keep them in neat piles on wooden shelves. We are Ann and Martin and have two dogs, Moose and Bug, both of whom hate art. East London is where we nurture our ideas, walk the dogs and meet people more talented than ourselves. Thank you for supporting us. You can find more of our books at: www.hoxtonminipress.com TOWER HAMLETS LOCAL HISTORY LIBRARY & ARCHIVES On his death in 1980, David Granick’s slides were deposited at his local public Visit us library on Bancroft Road, just a few minutes away from where he lived in Stepney. We hold many exhibitions and events, always free of charge, highlighting many At that time, the large Victorian building was the central lending library for the different aspects of East End history. But even if you can’t visit in person, feel free borough of Tower Hamlets with just one room for local history. Now, the whole to ask a question, add us on social media or sign up to our newsletter. For further building is dedicated to collecting, capturing and preserving materials and re- information about David Granick, our upcoming events and opening times, sources illustrating the amazing history of the borough. -

Blackshirts, Brownshirts & Leagues

Simone Veil Leon Greenman Anne Frank Noor Khan Primo Levi Esther Brunstein Gustav Schiefer First they came for the Holocaust survivor Witness to a new Diarist (1929-1945) Courageous Fighter Chronicler of Holocaust Survivor and Witness Anti Nazi Trade Unionist communists, and I did not and politician (1927- ) generation (1910-2008) (1914-1944) (1919-1987) (1928- ) (b. 1876) speak out—because I was not a Born in Frankfurt-am-Maim in communist; Simone Veil was interned in Born in London and taken Germany, Anne Frank’s family Born to an Indian father and Primo Levi was born in Turin, Esther Brunstein was born in Gustav Schiefer, Munich Chairman a Nazi concentration camp to Holland as a child, Leon went to Holland to escape Nazi American mother in Moscow, Italy. He was sent to Auschwitz Lodz, Poland. When the Nazis of the German Trade Union Then they came for the socialists, during the Second World War Greenman was arrested after persecution of Jews. Given a diary Noor Khan was an outstandingly in 1944. Managing to survive invaded in 1939 she was forced Association, was arrested, and I did not speak out—because because of her Jewish heritage. the Nazis invaded. He was for her 13th birthday she began brave woman. She escaped he later penned the poignant to wear a yellow star identifying beaten and imprisoned in Dachau I was not a socialist; After being liberated she subjected to experimentation to chronicle her forced hiding for from France after it fell to and moving book If this be a her as a Jew. -

View the Gazetteer

Street Location Abbey Road St John's Wood Aberdeen Park Highbury Aberdeen Terrace, Grove Road Old Ford* Acre Lane Brixton Addington Road Bow Addington Square Peckham Aden Terrace Stoke Newington Agar Grove Camden Town Albany Road Walworth Albany Street Regent's Park Albany Terrace Regent's Park Albemarle Street Mayfair Albert Road Regent's Park Albert Square Vauxhall Albert Street (= Bewley Street) Wapping Albert Street (= Deal Street) Whitechapel Albert Terrace, London Road Elephant & Castle Albion Road Barnsbury Albion Square De Beauvoir Albion Street Stoke Newington Alderney Road Mile End Aldersgate Street Clerkenwell Aldersgate Street Finsbury Aldgate High Street Aldgate Aldwych Holborn Alexandra Road St John's Wood Alfred Place Bloomsbury Alma Road Highbury Almorah Road Canonbury America Square Tower Hill Ampthill Square Euston Angel Court Aldgate Angel Court Covent Garden Angel Court, Honey Lane City Ann’s Buildingscopyright Petra Laidlaw Walworth* Arbour Square Whitechapel Arcola Street Stoke Newington Artillery Lane Spitalfields Artillery Place Finsbury Artillery Row Spitalfields Artillery Street Spitalfields Artizan Street Aldgate Arundel Gardens Notting Hill Aske Street Hoxton Avenue Road Swiss Cottage Back Church Lane Whitechapel Baker Street Marylebone Baker’s Row Whitechapel Baldwin Street Finsbury Balls Pond Road Dalston Bancroft Road Mile End Barbican Finsbury Barnes Buildings, Gravel Lane Aldgate Barnsbury Road Barnsbury Baroness Road Bethnal Green Barrett's Grove Stoke Newington Bartholomew Road Kentish Town Bassett Road