Catholic Priests and Seminarians As German Soldiers, 1935-1945

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM UVM Honors College Senior Theses Undergraduate Theses 2018 Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany William Peter Fitz University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses Recommended Citation Fitz, William Peter, "Reactionary Postmodernism? Neoliberalism, Multiculturalism, the Internet, and the Ideology of the New Far Right in Germany" (2018). UVM Honors College Senior Theses. 275. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses/275 This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in UVM Honors College Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REACTIONARY POSTMODERNISM? NEOLIBERALISM, MULTICULTURALISM, THE INTERNET, AND THE IDEOLOGY OF THE NEW FAR RIGHT IN GERMANY A Thesis Presented by William Peter Fitz to The Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of The University of Vermont In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Bachelor of Arts In European Studies with Honors December 2018 Defense Date: December 4th, 2018 Thesis Committee: Alan E. Steinweis, Ph.D., Advisor Susanna Schrafstetter, Ph.D., Chairperson Adriana Borra, M.A. Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter One: Neoliberalism and Xenophobia 17 Chapter Two: Multiculturalism and Cultural Identity 52 Chapter Three: The Philosophy of the New Right 84 Chapter Four: The Internet and Meme Warfare 116 Conclusion 149 Bibliography 166 1 “Perhaps one will view the rise of the Alternative for Germany in the foreseeable future as inevitable, as a portent for major changes, one that is as necessary as it was predictable. -

Theresienstadt Concentration Camp from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Coordinates: 50°30′48″N 14°10′1″E

Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Theresienstadt concentration camp From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Coordinates: 50°30′48″N 14°10′1″E "Theresienstadt" redirects here. For the town, see Terezín. Navigation Theresienstadt concentration camp, also referred to as Theresienstadt Ghetto,[1][2] Main page [3] was established by the SS during World War II in the fortress and garrison city of Contents Terezín (German name Theresienstadt), located in what is now the Czech Republic. Featured content During World War II it served as a Nazi concentration camp staffed by German Nazi Current events guards. Random article Tens of thousands of people died there, some killed outright and others dying from Donate to Wikipedia malnutrition and disease. More than 150,000 other persons (including tens of thousands of children) were held there for months or years, before being sent by rail Interaction transports to their deaths at Treblinka and Auschwitz extermination camps in occupied [4] Help Poland, as well as to smaller camps elsewhere. About Wikipedia Contents Community portal Recent changes 1 History The Small Fortress (2005) Contact Wikipedia 2 Main fortress 3 Command and control authority 4 Internal organization Toolbox 5 Industrial labor What links here 6 Western European Jews arrive at camp Related changes 7 Improvements made by inmates Upload file 8 Unequal treatment of prisoners Special pages 9 Final months at the camp in 1945 Permanent link 10 Postwar Location of the concentration camp in 11 Cultural activities and -

Uneeveningseveralyearsago

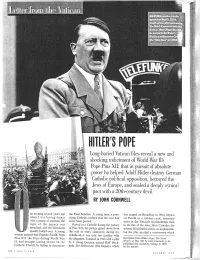

SUdfffiiUeraiKdiesavadio speechfinWay9,3934, »eariya3fearjafierannounce !Uie9leich£oncoRlati^3he Vatican.Aisei^flope^us )isseamed^SLIRetef^ Sa^caonVeconber ahe*»otyireaf'4Dfl9ra: 'i ' TlfraR Long-buried Vatican files reveal a new anc ; shocking indictment of World War IPs Jj; : - I • • H.t.-,. in n. ; Pope Pius XII: that in pursuit of absolute power he helped Adolf Hitler destroy German ^ Catholic political opposition, betrayed the Europe, and sealed a deeply cynica pact with a 20th-century devi!. BBI BY JOHN CORNWELL the Final Solution. A young man, a prac was staged on Broadway in 1964. depict UnewheneveningI wasseveralhavingyearsdinnerago ticing Catholic, insisted that the case had ed Pacelli as a ruthless cynic, interested with a group of students, the never been proved. more in the Vatican's stockholdings than topic of the papacy was Raised as a Catholicduring the papacy in the fate of the Jews. Most Catholics dis broached, and the discussion of Pius XII—his picture gazed down from missed Hochhuth's thesis as implausible, quickly boiled over. A young the wall of every classroom during my but the play sparked a controversy which woman asserted that Eugenio Pacelli, Pope childhood—I was only too familiar with Pius XII, the Pope during World War the allegation. It started in 1963 with a play Excerpted from Hitler's Pope: TheSeci-et II, had brought lasting shame on the by a young German named Rolf Hoch- History ofPius XII. bj' John Comwell. to be published this month byViking; © 1999 Catholic Church by failing to denounce huth. DerStellverti-eter (The Deputy), which by the author. VANITY FAIR OCTOBER 1999 having reliable knowl- i edge of its true extent. -

Pius XII on Trial

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College 5-2014 Pius XII on Trial Katherine M. Campbell University of Maine - Main, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Anthropology Commons, and the History Commons Recommended Citation Campbell, Katherine M., "Pius XII on Trial" (2014). Honors College. 159. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors/159 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PIUS XII ON TRIAL by Katherine M. Campbell A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Anthropology and Political Science) The Honors College University of Maine May 2014 Advisory Committee: Henry Munson, Professor of Anthropology Alexander Grab, Professor of History Mark D. Brewer, Associate Professor of Political Science Richard J. Powell, Associate Professor of Political Science, Leadership Studies Sol Goldman, Adjunct Assistant Professor of Political Science Copyright 2014 Katherine M. Campbell Abstract: Scholars have debated Pope Pius XII’s role in the Holocaust since the 1960s. Did he do everything he could and should have done to save Jews? His critics say no because of antisemitism rooted in the traditional Catholic views. His defenders say yes and deny that he was an antisemite. In my thesis, I shall assess the arguments on both sides in terms of the available evidence. I shall focus both on what Pius XII did do and what he did not do and on the degree to which he can be held responsible for the actions of low-level clergy. -

Vortrag Hummel Engl

Prof em Dr Karl-Joseph Hummel Berlin, 30 June 2018 Martyrs: Remembrance, the sine qua non for a reconciled future I The generation with personal experience There was no doubt whatever among those witnesses who were able to give a first-hand account of the Third Reich in 1945, the “terrible year of grace” (Reinhold Schneider), both inside and outside Germany, that the period of National Socialism had left behind it a massive amount of guilt. The question, which was and is disputed, is who had what share of it. The religious sister Isa Vermehren, who herself was incarcerated in a concentration camp, described the dilemma as follows in her “Witness from a dark past”: “It was not easy to remain innocent in the Nazi period. If you were innocent in the eyes of the Nazis, you were hardly innocent in terms of your own conscience – if you retained a clear conscience, you were hardly innocent in the eyes of the Nazis.” At that time, the Church and Catholics regarded themselves – to a highly prevalent degree – as standing together on the side of the victims. The spectrum of self-perception ranged from the assessment of the concentration camp inmate and later Munich Auxiliary Bishop Neuhäusler “Resistance was powerful and dogged, at the top and at the bottom, coming from the Pope and the bishops, from the clergy and the people, from individuals and whole organisations.” (ideological resistance), to the examination of conscience of Albrecht Haushofer, who for many years was friends with Rudolf Heß, and who was arrested after 20 July 1944 and later shot by the SS: Haushofer wrote in a sonnet from prison in Moabit: “I bear lightly what the court will call my guilt.. -

Wörrstadt / Gau Odernheim

Gültig ab 2. September 2019 Q 441 Wörrstadt / Gau Odernheim - Gabsheim - Saulheim (- Nieder-Olm) Q An Rosenmontag und Fastnachtdienstag, sowie Freitag nach Christi Himmelfahrt und nach Fronleichnam, Verkehr wie in den Ferien.Am 24. und 31.12. Verkehr wie Samstag Am 01.11. und Fronleichnam Verkehr wie an Sonn- und Feiertagen Montag - Freitag 0441 0441 0441 0441 0441 0441 0441 0441 0441 0441 0441 0441 0441 0441 0441 0000 0441 0441 0441 101 301 103 901 303 803 305 805 307 309 311 313 909 911 315 915 317 319 Verkehrsbeschränkungen S F S F S S S F S S004 Hinweise Gau-Odernheim Marktplatz .559 .7 59 .7 59 .9 59 11. 59 12. 42 13. 59 Gau-Odernheim Mainzer Straße .601 .8 01 .8 01 10. 01 12. 01 12. 44 14. 01 Bechtolsheim Musikhalle 12.47 Bechtolsheim Rathaus 12.48 Bechtolsheim Brückesgasse 12.49 Biebelnheim Ortsmitte .604 .8 04 .8 04 10. 04 12. 04 12. 51 14. 04 Wörrstadt Bahnhof .658 .6 58 .8 58 10.58 12.58 13. 10 14.58 Wörrstadt Schulzentrum 13.15 13. 15 Wörrstadt Friedrich-Ebert-Straße .700 .7 00 .9 00 11.00 13.00 15.00 Wörrstadt Rommersheimer Straße 13.16 Wörrstadt Rommersheimer Straße .702 .7 02 .9 02 11.02 13.02 15.02 Wörrstadt Pariser Straße .703 .7 03 .9 03 11.03 13.03 13. 17 15.03 Gabsheim Unterpforte .543 .6 10 .6 38 .7 04 .7 10 .7 10 .8 10 .8 10 .9 10 10. 10 11. 10 12. 10 12. 57 13. -

USHMM Finding

http://collections.ushmm.org Contact [email protected] for further information about this collection RG-50.862: EHRLICH COLLECTION - SUMMARY NOTES OF AUDIO FILES Introductory note by Anatol Steck, Project Director in the International Archival Programs Division of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum: These summary transcription notes of the digitized interviews recorded by Leonard and Edith Ehrlich in the 1970s as part of their research for their manuscript about the Jewish community leadership in Vienna and Theresienstadt during the Holocaust titled "Choices under Duress" are a work in progress. The project started in April 2016 and is ongoing. The summary notes are being typed while listening to the recordings in real time; this requires simultaneous translation as many of the interviews are in German, often using Viennese vernacular and/or Yiddish terms (especially in the case of the lengthy interview with Benjamin Murmelstein which the Ehrlichs recorded with Mr. and Mrs. Murmelstein over several days in their apartment in Rome and which constitutes a major part of this collection). The summary notes are intended as a tool and a finding aid for the researcher; researchers are strongly encouraged to consult the digitized recordings for accuracy and authenticity and not to rely solely on the summary notes. As much as possible, persons mentioned by name in the interviews are identified and described in the text; however, as persons are often referred to in the interviews only by last name, their identification is sometimes based on the context in which their names appear within the interview (especially in cases where different persons share the same last name). -

The United States Atomic Army, 1956-1960 Dissertation

INTIMIDATING THE WORLD: THE UNITED STATES ATOMIC ARMY, 1956-1960 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Paul C. Jussel, B.A., M.M.A.S., M.S.S. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee Approved by Professor Allan R. Millett, Advisor Professor John R. Guilmartin __________________ Professor William R. Childs Advisor Department of History ABSTRACT The atomic bomb created a new military dynamic for the world in 1945. The bomb, if used properly, could replace the artillery fires and air-delivered bombs used to defeat the concentrated force of an enemy. The weapon provided the U.S. with an unparalleled advantage over the rest of the world, until the Soviet Union developed its own bomb by 1949 and symmetry in warfare returned. Soon, theories of warfare changed to reflect the belief that the best way to avoid the effects of the bomb was through dispersion of forces. Eventually, the American Army reorganized its divisions from the traditional three-unit organization to a new five-unit organization, dubbed pentomic by its Chief of Staff, General Maxwell D. Taylor. While atomic weapons certainly had an effect on Taylor’s reasoning to adopt the pentomic organization, the idea was not new in 1956; the Army hierarchy had been wrestling with restructuring since the end of World War II. Though the Korean War derailed the Army’s plans for the early fifties, it returned to the forefront under the Eisenhower Administration. The driving force behind reorganization in 1952 was not ii only the reoriented and reduced defense budget, but also the Army’s inroads to the atomic club, formerly the domain of only the Air Force and the Navy. -

Ortsgemeinde Bechtolsheim Niederschrift

Ortsgemeinde Bechtolsheim Öffentlicher Teil der Niederschrift über die 16. Sitzung des Gemeinderates der Ortsgemeinde Bechtolsheim der Wahlperiode 2019 – 2024 am 13. Juli 2021 in der Musikhalle der Ortsgemeinde Bechtolsheim Beginn: 19:01 Uhr Ende: 21:00 Uhr SITZUNGSTEILNEHMER Stimmrecht ANWESEND: Name Funktion Bemerkung Mann, Dieter Ortsbürgermeister und Vorsitzender ja Dr. Strecker, Harald Erster Beigeordneter u. Ratsmitglied ja Uhink, Mathias Beigeordneter u. Ratsmitglied ja Borlinghaus, Axel Ratsmitglied ja Brand, Gerhard Ratsmitglied ja Breivogel, Sylvia Ratsmitglied ja Dolata, Jens Ratsmitglied ja Eisenbarth, Holger Ratsmitglied ja Flick, Ronald Ratsmitglied ja Jennewein, Albert Ratsmitglied ab 19.05 Uhr; vor Abstimmung zu TOP 1 ja Maas, Helmut Ratsmitglied ja Müller, Thilo Ratsmitglied ja Scherning, Frank Ratsmitglied ja Schmelzer, Sandra Ratsmitglied ja Ullmer, Kai Ratsmitglied ja Wieland, Annedore Ratsmitglied ja Öffentlicher Teil der Niederschrift über die 16. Sitzung des Gemeinderates der Ortsgemeinde Bechtolsheim am 13.07.2021 NICHT ANWESEND: Name Funktion Bemerkung Jennewein, Sabrina Ratsmitglied entschuldigt SCHRIFTFÜHRER - VERWALTUNGSMITARBEITER Name Funktion Bemerkung Druck, Sabrina Schriftführerin GÄSTE / ZUHÖRER Name Funktion Bemerkung Göck, Horst Flick, Rudolf Schwarz, Christina Weinheimer, Ludwig Wollny, Hugo 2 Öffentlicher Teil der Niederschrift über die 16. Sitzung des Gemeinderates der Ortsgemeinde Bechtolsheim am 13.07.2021 Ortsbürgermeister und Vorsitzender Dieter Mann begrüßt die Anwesenden. Er stellt fest, dass mit Schreiben vom 05.07.2021 form- und fristgerecht gemäß § 34 Absatz 2 der Gemeindeordnung zur Sitzung eingeladen wurde. Wegen der Corona-Pandemie findet die 15. Sitzung des Ortsgemeinderates in der Musikhalle und unter Beachtung der geltenden Hygienevorschriften statt. Die Abstandsregelungen werden eingehalten; Desinfektionsmittel und Mikrofone stehen zur Verfügung. Zutritt zum Saal und den Toiletten ist nur einzeln und mit Mundschutz gestattet. -

The Forgotten Fronts the First World War Battlefield Guide: World War Battlefield First the the Forgotten Fronts Forgotten The

Ed 1 Nov 2016 1 Nov Ed The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The Forgotten Fronts The First Battlefield War World Guide: The Forgotten Fronts Creative Media Design ADR005472 Edition 1 November 2016 THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | i The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The British Army Campaign Guide to the Forgotten Fronts of the First World War 1st Edition November 2016 Acknowledgement The publisher wishes to acknowledge the assistance of the following organisations in providing text, images, multimedia links and sketch maps for this volume: Defence Geographic Centre, Imperial War Museum, Army Historical Branch, Air Historical Branch, Army Records Society,National Portrait Gallery, Tank Museum, National Army Museum, Royal Green Jackets Museum,Shepard Trust, Royal Australian Navy, Australian Defence, Royal Artillery Historical Trust, National Archive, Canadian War Museum, National Archives of Canada, The Times, RAF Museum, Wikimedia Commons, USAF, US Library of Congress. The Cover Images Front Cover: (1) Wounded soldier of the 10th Battalion, Black Watch being carried out of a communication trench on the ‘Birdcage’ Line near Salonika, February 1916 © IWM; (2) The advance through Palestine and the Battle of Megiddo: A sergeant directs orders whilst standing on one of the wooden saddles of the Camel Transport Corps © IWM (3) Soldiers of the Royal Army Service Corps outside a Field Ambulance Station. © IWM Inside Front Cover: Helles Memorial, Gallipoli © Barbara Taylor Back Cover: ‘Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red’ at the Tower of London © Julia Gavin ii | THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | iii ISBN: 978-1-874346-46-3 First published in November 2016 by Creative Media Designs, Army Headquarters, Andover. -

MICROCOSM: Portrait of a European City Major Disturbance

In Breslau, the overthrow of the imperial authorities passed off without MICROCOSM: Portrait of a European City major disturbance. On 8 November, a Loyal Appeal for the citizens to uphold by Norman Davies (pp. 326-379) their duties to the Kaiser was distributed in the names of the Lord Mayor, Paul Matting, Archbishop Bertram and others. But it had no great effect. The Commander of the VI Army Corps, General Pfeil, was in no mood for a fight. Breslau before and during the Second World War He released the political prisoners, ordered his men to leave their barracks, 1918-45 and, in the last order of the military administration, gave permission to the Social Democrats to hold a rally in the Jahrhunderthalle. The next afternoon, a The politics of interwar Germany passed through three distinct phases. In group of dissident airmen arrived from their base at Brieg (Brzeg). Their arrival 1918-20, anarchy spread far and wide in the wake of the collapse of the spurred the formation of 'soldiers' councils' (that is, Soviets) in several military German Empire. Between 1919 and 1933, the Weimar Republic re-established units and of a 100-strong Committee of Public Safety by the municipal leaders. stability, then lost it. And from 1933 onwards, Hitler's 'Third Reich' took an The Army Commander was greatly relieved to resign his powers. ever firmer hold. Events in Breslau, as in all German cities, reflected each of The Volksrat, or 'People's Council', was formed on 9 November 1918, from the phases in turn. Social Democrats, union leaders, Liberals and the Catholic Centre Party. -

Janusz Odziemkowski Bitwa Nad Autą, 4–6 Lipca 1920 Roku

Janusz Odziemkowski Bitwa nad Autą, 4–6 lipca 1920 roku Przegląd Historyczno-Wojskowy 14(65)/1 (243), 51-74 2013 JANUSZ ODZIEMKOWSKI bitWa nad autą, 4–6 lipca 1920 roku dniach 4–6 lipca 1920 r. na północnym odcinku frontu polsko-rosyj- skiego, rozciągającego się od dolnej Dźwiny po ukrainne stepy, 1 Armia gen. Gustawa Zygadłowicza toczyła walki z wojskami Frontu Zachodnie- Wgo Michaiła Tuchaczewskiego. Przeszły one do historii jako „bitwa nad Autą”, od nazwy rzeki, na której była oparta obrona centrum zgrupowania 1 Armii. Bitwę nad Autą trzeba zaliczyć do najważniejszych wydarzeń wojny Rzeczypospolitej z Rosją bolszewicką. Zapoczątkowała ona bowiem odwrót wojsk polskich na Białorusi i Li- twie, przejęcie inicjatywy przez przeciwnika, którego rozpoczęty wówczas pochód na zachód został zatrzymany dopiero po 6 tygodniach na przedpolach Warszawy. Mimo tych okoliczności bitwa nie doczekała się szerszego opracowania w polskiej literaturze historycznowojskowej, nie zajmuje też zatem właściwego jej miejsca w świadomości historycznej społeczeństwa. Zasadnicze kwestie związane z bitwą nad Autą dotykają dwóch zagadnień: przy- czyn porażki 1 Armii oraz związanego z tym pytania, czy przy ówczesnym stosunku sił na północnym odcinku frontu przegranej można było uniknąć lub przynajmniej zminimalizować jej skutki. TEREN Bitwa rozegrała się na froncie o szerokości około 100 km, rozciągającym się od rzeki Dźwiny w rejonie Dryssy na północy, po bagna górnej Berezyny na południu. Wysunięty najdalej na północ odcinek frontu 1 Armii obejmował obszar o szerokości około 20 km, usytuowany między Dźwiną skręcającą w tym miej- scu na północny zachód, a jej lewobrzeżnym dopływem – Dzisną. Mniej więcej w centrum tego obszaru leży jezioro Jelnia. W 1920 r.